Fundamentals

You have likely sat in a physician’s office, looked at a lab report, and seen a number next to “Total Cholesterol.” For decades, this single metric, along with its companions LDL and HDL, has been the primary language of cardiovascular risk.

You may have felt a sense of unease, a feeling that such a simple number fails to capture the complexity of your own body, your unique symptoms, or your family history. Your intuition is correct. The conventional lipid panel provides an incomplete picture, akin to judging the state of a bustling metropolis by looking only at a single highway.

A deeper, more precise understanding of cardiovascular health requires a more sophisticated vocabulary, one that moves from broad estimates to direct measurements of the agents responsible for vascular disease. This journey begins by asking more specific questions about the biological actors that drive the process of atherosclerosis.

The conversation about cardiovascular risk is evolving, moving toward a framework built on three foundational pillars that offer far greater predictive power. These pillars are Apolipoprotein B (ApoB), Lipoprotein(a) or Lp(a), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP).

Together, they provide a multi-dimensional view of your risk, accounting for the quantity of atherogenic particles, your inherent genetic predispositions, and the level of systemic inflammation that promotes arterial damage. Understanding these biomarkers is the first step in reclaiming agency over your health narrative, transforming you from a passive observer of your lab values into an informed architect of your own wellness.

True cardiovascular risk assessment extends beyond standard cholesterol tests to include direct measures of atherogenic particles, genetic factors, and inflammation.

Apolipoprotein B the Particle Count

Imagine a highway filled with cars, each carrying a cargo of cholesterol. The standard LDL-C measurement is like estimating the total weight of the cargo in all the cars. This metric tells you something, yet it misses a critical piece of information ∞ the actual number of cars on the road.

Apolipoprotein B, or ApoB, provides this exact count. ApoB is a structural protein, with one molecule tethered to every potentially atherogenic lipoprotein particle, including LDL, VLDL, and IDL. Therefore, measuring ApoB gives us a direct tally of the total number of these particles circulating in your bloodstream.

The number of these particles is the primary driver of atherosclerosis. Each particle represents an opportunity for cholesterol to be deposited into the artery wall, initiating the formation of plaque. When there is a high traffic volume of these ApoB-containing particles, the probability of arterial wall infiltration increases substantially.

This is particularly true for individuals with smaller, denser LDL particles, a common feature of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. In these cases, the LDL-C measurement can appear deceptively normal because each particle carries less cholesterol, while the ApoB count, revealing the high particle number, correctly identifies the elevated risk. Measuring ApoB is the definitive method for quantifying the concentration of atherogenic lipoproteins.

Lipoprotein(a) a Genetically Influenced Factor

While ApoB quantifies the number of potentially harmful particles, Lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), identifies a specific, genetically determined subtype of lipoprotein with unique properties. You can think of Lp(a) as a specialized LDL particle with an additional, highly adhesive protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached to it.

This structural modification gives Lp(a) a dual-threat capability. It contributes to plaque buildup just like a standard LDL particle, and its adhesive nature also promotes blood clot formation and localized inflammation within the artery wall.

Your Lp(a) level is predominantly determined by your genes, with levels remaining relatively stable throughout your lifetime, irrespective of diet, exercise, or most conventional lipid-lowering therapies. A high Lp(a) level represents a lifelong, independent risk factor for cardiovascular events.

Because of its genetic basis, it can explain why some individuals with otherwise perfect health habits and normal cholesterol panels still suffer from premature heart disease. The European Society of Cardiology and European Atherosclerosis Society now recommend a once-in-a-lifetime measurement for every adult to identify this important and often hidden risk.

High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein the Inflammatory Signal

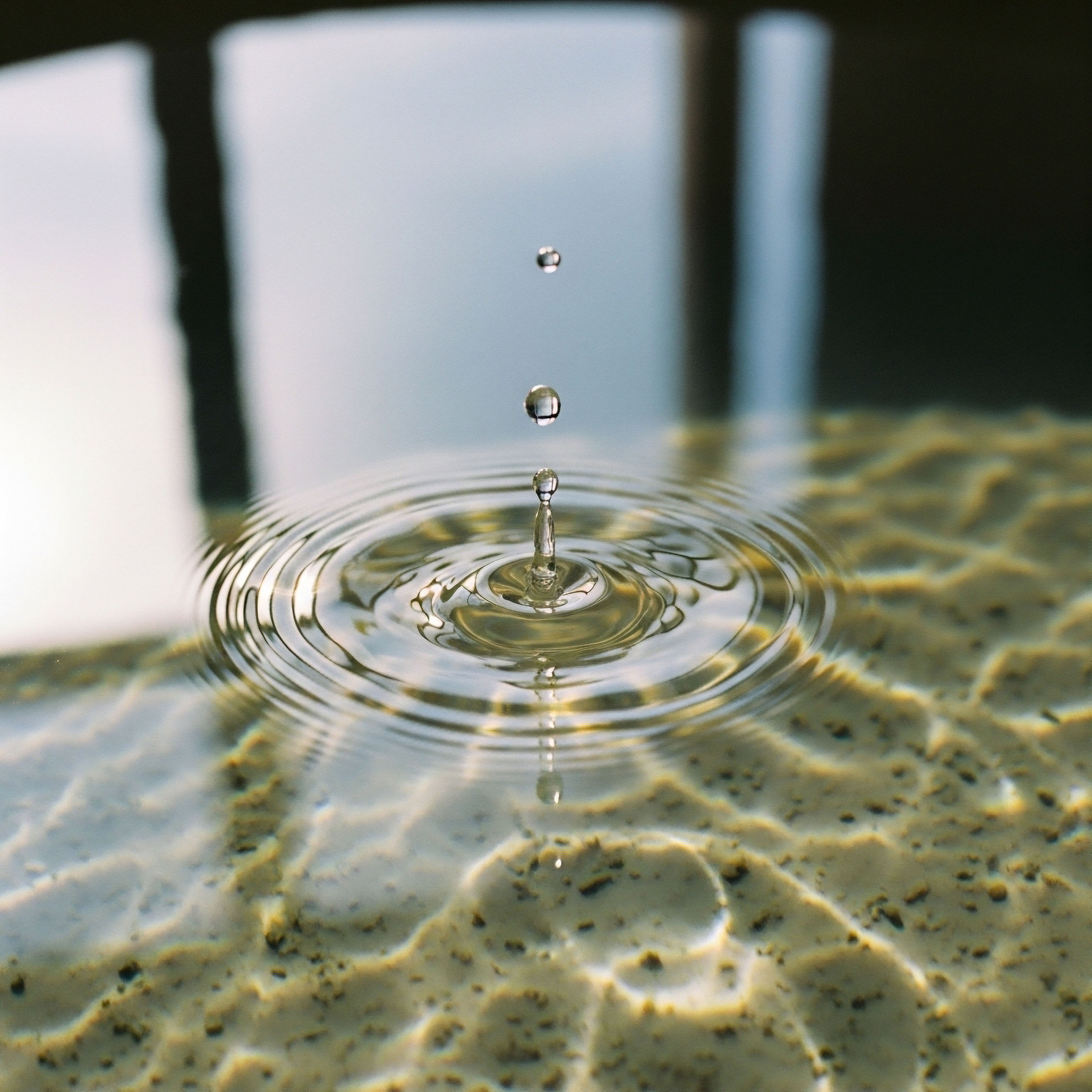

Atherosclerosis is a disease process rooted in chronic, low-grade inflammation. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) is the most validated and clinically useful biomarker for measuring this underlying inflammatory state.

Produced by the liver in response to inflammatory signals, hs-CRP serves as a systemic “fire alarm,” indicating that the body’s immune system is activated and engaged in a low-level, persistent battle within the arterial walls. This smoldering inflammation damages the delicate lining of the arteries, making them more susceptible to infiltration by ApoB-containing particles and accelerating the growth of atherosclerotic plaques.

Elevated hs-CRP levels are a powerful, independent predictor of future heart attacks and strokes, even in individuals with low cholesterol levels. Research has consistently shown that when hs-CRP is high, cardiovascular risk is elevated, regardless of LDL-C values. This biomarker provides a crucial window into the physiological environment in which atherosclerosis develops.

It helps quantify the “active” component of the disease, reflecting the dynamic interplay between the immune system and the vascular wall. Integrating hs-CRP with ApoB and Lp(a) creates a comprehensive risk profile that accounts for particle burden, genetic susceptibility, and the inflammatory processes that fuel disease progression.

Intermediate

Advancing from a foundational knowledge of ApoB, Lp(a), and hs-CRP to an intermediate understanding requires a deeper examination of their clinical application and their intricate relationship with the endocrine system. These biomarkers are not static numbers on a page; they are dynamic indicators that reflect the complex interplay between your metabolic health, your hormonal status, and your vascular system.

Understanding how to interpret these values in concert, and recognizing how they are influenced by hormonal shifts throughout life, provides a powerful toolkit for personalized risk stratification and intervention. This level of analysis moves from identifying risk to understanding its drivers, creating a pathway for targeted, effective health optimization.

Clinical Nuances in Biomarker Interpretation

The true clinical utility of these advanced biomarkers is realized when they are analyzed together, as they each tell a different part of the same story. The concept of discordance analysis is central to this approach, particularly regarding ApoB and LDL-C.

ApoB and LDL-C Discordance

Discordance occurs when LDL-C and ApoB levels tell conflicting stories. An individual might have a “normal” or even “low” LDL-C, yet possess a high ApoB concentration. This scenario, known as discordant hyper-apoB, is common in states of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.

In these conditions, the body produces an abundance of small, dense LDL particles. Each particle carries less cholesterol than its larger, more buoyant counterpart, leading to a lower overall LDL-C measurement. The ApoB value, however, accurately reflects the high number of these highly atherogenic particles, unmasking the true cardiovascular risk that LDL-C alone would have missed. When LDL-C and ApoB are discordant, your risk follows ApoB.

Lp(a) Contextual Risk

The risk conferred by an elevated Lp(a) is magnified by the presence of other risk factors. For instance, a person with a high Lp(a) and a high ApoB has a substantially greater risk than someone with a high Lp(a) alone.

The high particle number from ApoB provides more vehicles for arterial wall infiltration, while the Lp(a) ensures that this process is more aggressive and thrombotic. Similarly, the combination of high Lp(a) and high hs-CRP is particularly potent, as the genetic predisposition to atherothrombosis is occurring within a pro-inflammatory environment that accelerates plaque instability and rupture.

This is why assessing Lp(a) in isolation is insufficient; its predictive power is best understood within the context of an individual’s complete biomarker profile.

Hormonal fluctuations throughout life, particularly changes in testosterone and estrogen, directly modulate the advanced biomarkers that govern cardiovascular risk.

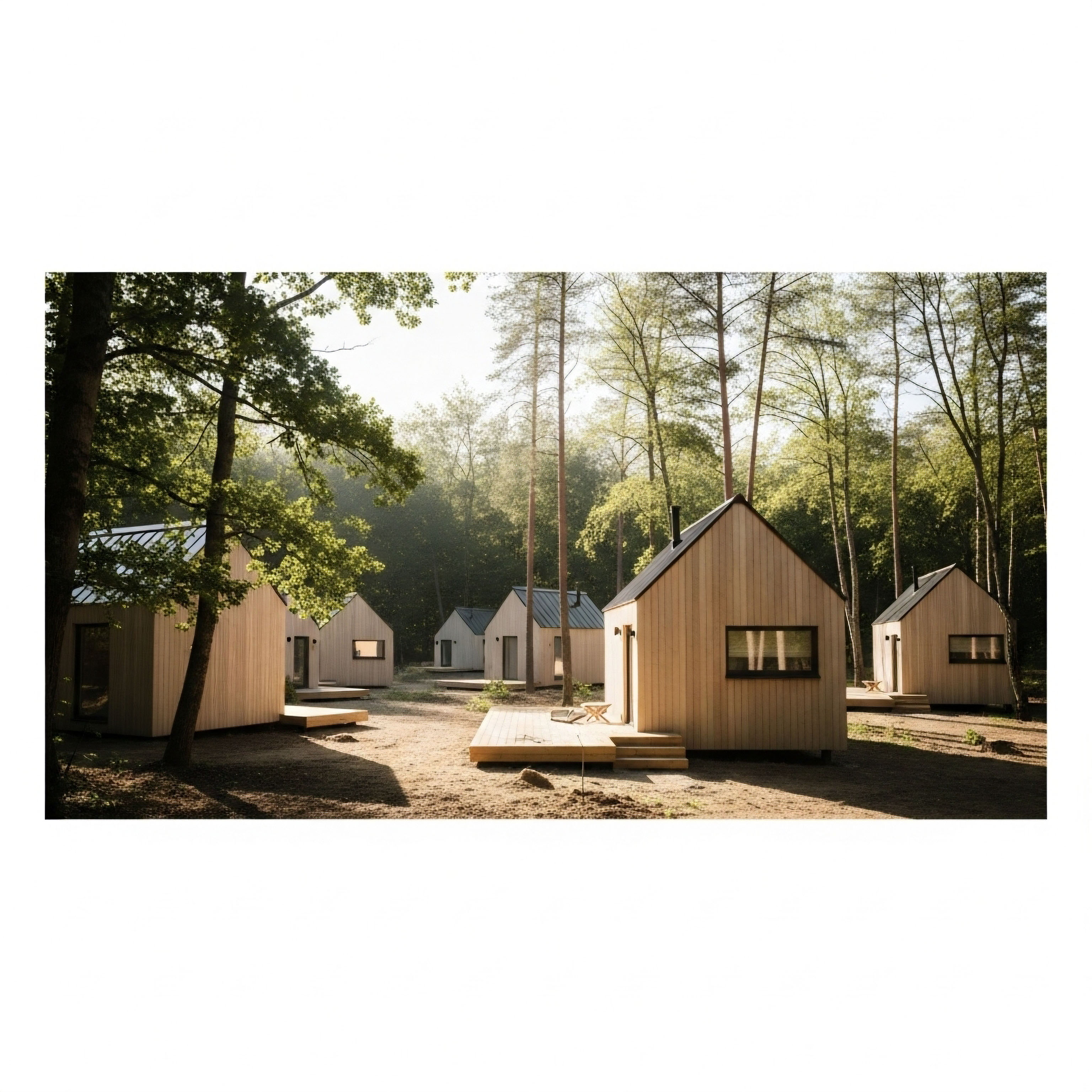

The Endocrine System as a Master Regulator

The endocrine system, through its complex web of hormonal messengers, exerts profound control over lipid metabolism and inflammation. Hormonal changes, whether due to aging, lifestyle, or therapeutic intervention, can significantly alter your cardiovascular biomarker profile. Recognizing this connection is fundamental to a holistic approach to health.

Testosterone’s Role in Male Cardiometabolic Health

In men, testosterone functions as a key metabolic regulator. Declining testosterone levels, a hallmark of andropause, are strongly associated with an adverse shift in cardiometabolic health. Low testosterone is linked to increased visceral fat, worsening insulin resistance, and a more atherogenic lipid profile.

Specifically, men with low testosterone often exhibit higher ApoB concentrations and lower HDL-C levels. This hormonal decline fosters an environment conducive to the development of metabolic syndrome, which in turn drives up the production of small, dense LDL particles.

Testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), when clinically indicated and properly managed, can help reverse these trends. Protocols involving Testosterone Cypionate, often balanced with agents like Anastrozole to control estrogen conversion and Gonadorelin to maintain testicular function, can improve insulin sensitivity, reduce visceral fat, and lead to a more favorable lipid profile, including a potential reduction in ApoB. By restoring hormonal balance, these protocols address a root cause of metabolic dysfunction, thereby mitigating cardiovascular risk at a fundamental level.

Estrogen’s Vascular Protection in Women

In women, estrogen is a powerful vasoprotective hormone. It promotes endothelial health, supports healthy vasodilation, and has a favorable impact on lipid metabolism. During the premenopausal years, estrogen helps maintain lower ApoB and LDL-C levels and higher HDL-C levels. The transition into perimenopause and post-menopause, marked by a steep decline in estrogen production, represents a period of accelerated cardiovascular risk.

This hormonal shift often triggers a rise in ApoB and a shift toward smaller, denser LDL particles. Systemic inflammation, as measured by hs-CRP, also tends to increase as the anti-inflammatory effects of estrogen wane. Judicious use of hormone replacement therapy can mitigate these changes.

Protocols using bioidentical estradiol, often paired with progesterone to protect the uterus, can help preserve a more favorable lipid profile and control inflammation. For some women, the addition of low-dose testosterone can further enhance metabolic function and overall well-being. These interventions are designed to buffer the cardiometabolic consequences of menopause, supporting long-term vascular health.

The following table illustrates the comparative value of standard and advanced biomarker panels.

| Biomarker Type | Standard Panel | Advanced Panel |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Measurement | Indirect (LDL-C, calculated) | Direct (ApoB, particle count) |

| Genetic Risk | Not assessed | Assessed (Lp(a)) |

| Inflammation | Not assessed | Assessed (hs-CRP) |

| Clinical Utility | Broad population screening | Personalized risk stratification |

Understanding who benefits most from this advanced testing is key to its effective implementation.

- Individuals with a family history of premature cardiovascular disease, whose risk may be driven by genetic factors like high Lp(a).

- People with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, or type 2 diabetes, who are prone to high ApoB levels even with normal LDL-C.

- Those with autoimmune conditions or other chronic inflammatory states, where hs-CRP can provide critical prognostic information.

- Asymptomatic individuals seeking a more precise understanding of their long-term risk to guide proactive lifestyle and therapeutic decisions.

Academic

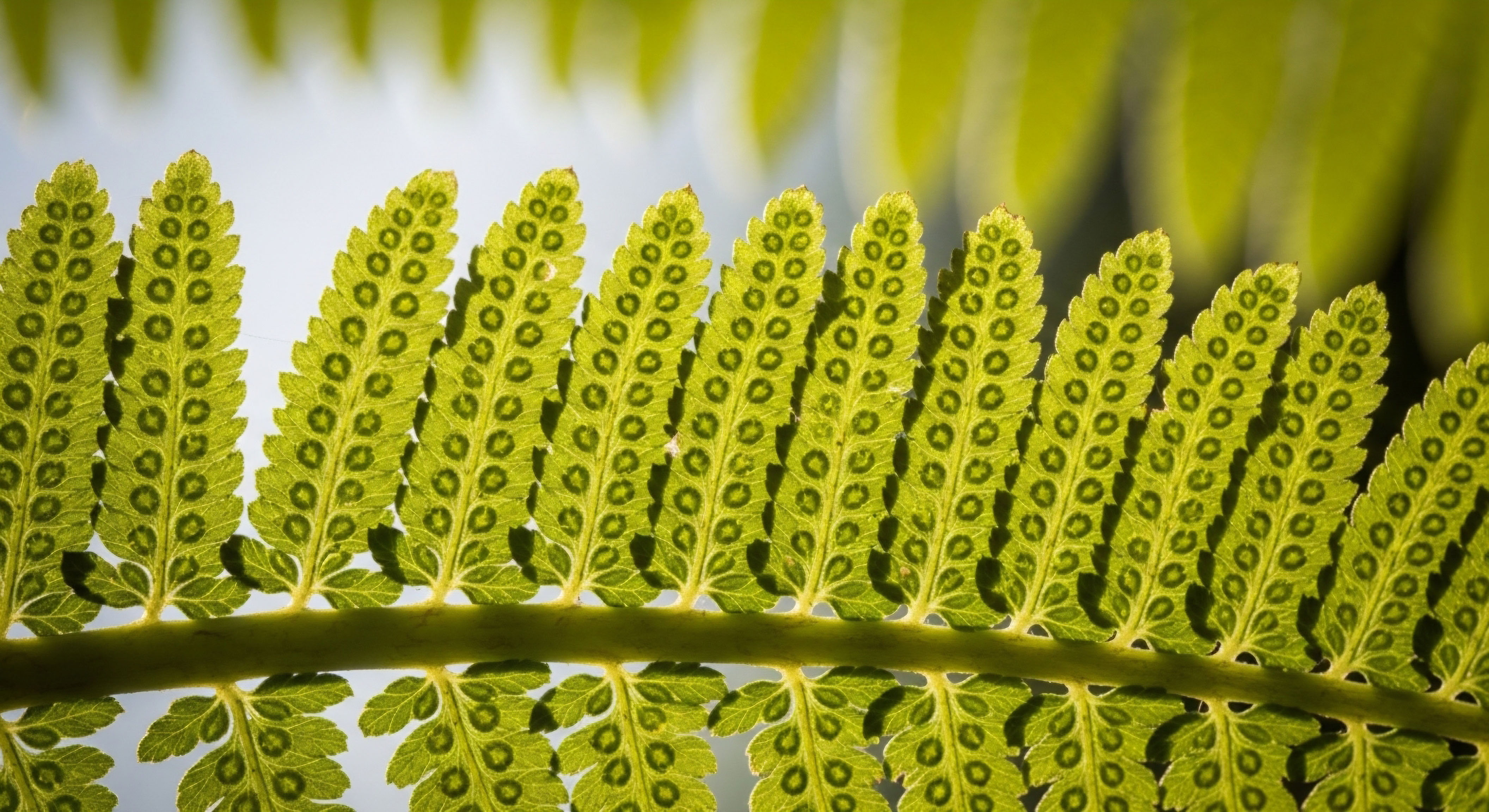

At the most granular level of vascular biology, the predictive power of Apolipoprotein B, Lipoprotein(a), and hs-CRP can be understood as downstream manifestations of a more fundamental process ∞ the degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx. This delicate, carbohydrate-rich layer lining the inner surface of all blood vessels is the true gatekeeper of vascular health.

It functions as a sophisticated biosensor, a dynamic physical barrier, and the master regulator of endothelial function. Its structural and functional integrity is paramount for preventing the initiation of atherosclerosis. From an academic perspective, the most advanced understanding of cardiovascular risk involves viewing ApoB, Lp(a), and inflammation not as independent agents, but as interacting factors that contribute to the progressive erosion of this critical protective shield.

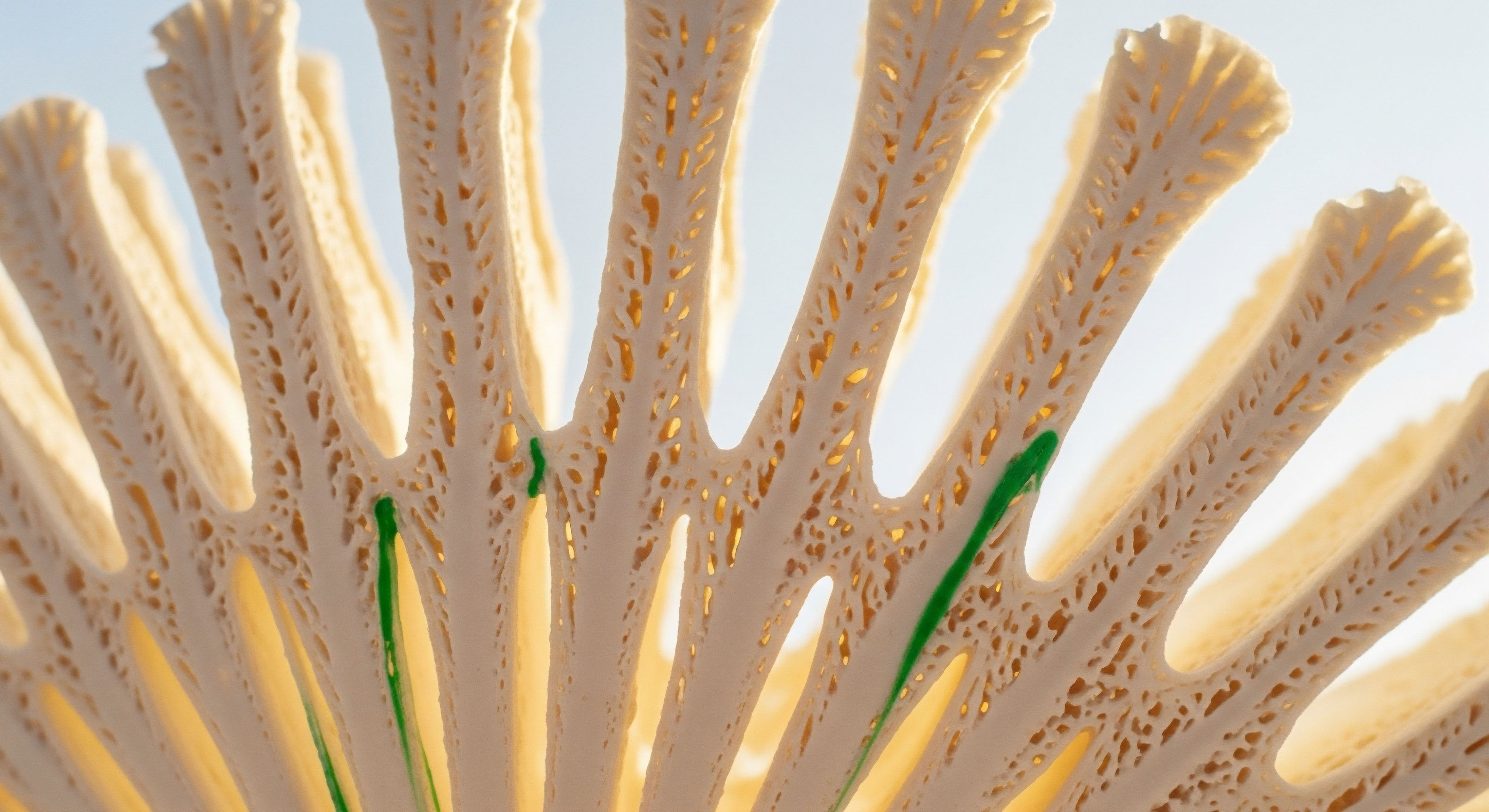

The Endothelial Glycocalyx a Systems Perspective

The endothelial glycocalyx (GCX) is a complex matrix of membrane-bound proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and associated glycosaminoglycans that extends into the vessel lumen. This structure is far from being a passive coating; it is a highly active interface that translates mechanical forces, such as blood flow shear stress, into biochemical signals that regulate vascular tone and health. A healthy GCX performs several critical vasculoprotective functions:

- Size and Charge Barrier ∞ The dense network of the GCX creates a physical barrier that repels large molecules, including lipoproteins, and its net negative charge electrostatically repels negatively charged particles like LDL. This action severely limits the passage of atherogenic lipoproteins into the subendothelial space, the site of plaque formation.

- Mechanotransduction ∞ The GCX acts as the primary sensor of blood flow. Shear stress on the GCX triggers a cascade of intracellular signaling that leads to the production of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator and anti-inflammatory molecule. This mechanism is essential for maintaining normal blood pressure and inhibiting platelet aggregation and leukocyte adhesion.

- Inflammation and Thrombosis Regulation ∞ The GCX sequesters and regulates a host of molecules involved in coagulation and inflammation, effectively creating an anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory surface. It prevents direct contact between circulating blood cells and endothelial adhesion molecules.

The initiation of atherosclerosis is preceded by, and mechanistically linked to, the degradation of the GCX. When this protective layer is compromised, the endothelium shifts to a dysfunctional, pro-atherogenic state.

How Do Advanced Biomarkers Relate to Glycocalyx Degradation?

The “big three” advanced biomarkers are intimately involved in the process of GCX injury, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of vascular damage.

ApoB and Infiltration

A high concentration of ApoB-containing particles represents a relentless physical and biochemical assault on the GCX. Increased particle number overwhelms the barrier function of the GCX, increasing the statistical probability of penetration. Furthermore, oxidative modification of these LDL particles, a common occurrence in pro-inflammatory states, generates molecules that can directly induce enzymatic degradation of the GCX, creating localized breaches in the protective shield.

Once the barrier is penetrated, these particles become trapped in the subendothelial space, where they are engulfed by macrophages, leading to the formation of foam cells, the earliest pathological hallmark of an atherosclerotic lesion.

Lp(a) and Targeted Disruption

Lp(a) contributes to GCX degradation through more specific mechanisms. The unique apolipoprotein(a) component can bind to components of the extracellular matrix, effectively anchoring the particle to the endothelial surface. This prolonged contact facilitates lipid deposition and promotes the generation of inflammatory and thrombotic mediators directly at the GCX interface.

The structural similarity of apolipoprotein(a) to plasminogen allows it to interfere with fibrinolysis, the process of breaking down blood clots. This dual action makes Lp(a) a potent force for creating a pro-thrombotic, pro-inflammatory microenvironment that accelerates both GCX breakdown and the development of complex plaques.

hs-CRP and Enzymatic Shedding

Systemic inflammation, indicated by an elevated hs-CRP, is a primary driver of GCX degradation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and Interleukin-1, whose activity is reflected by hs-CRP levels, stimulate endothelial cells to produce enzymes such as heparanase and matrix metalloproteinases.

These enzymes act like molecular scissors, cleaving the proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans from the endothelial surface and causing the GCX to be “shed” into the circulation. This enzymatic degradation destroys the barrier, impairs NO production, and exposes adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface, facilitating the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the vessel wall. This process explains why inflammation is a critical accelerator of atherosclerosis; it directly dismantles the primary defense mechanism of the artery.

The integrity of the endothelial glycocalyx is the ultimate determinant of vascular health, with its degradation serving as the common pathway through which atherogenic particles and inflammation initiate disease.

This table details the specific mechanisms by which key factors damage the endothelial glycocalyx.

| Factor | Mechanism of Glycocalyx Damage | Resulting Vascular Dysfunction |

|---|---|---|

| High ApoB Particle Number | Overwhelms physical barrier; oxidative modification induces enzymatic degradation. | Increased lipid infiltration; foam cell formation. |

| Elevated Lipoprotein(a) | Binds to endothelial surface; interferes with fibrinolysis. | Localized inflammation; pro-thrombotic state. |

| Systemic Inflammation (High hs-CRP) | Induces shedding enzymes (e.g. heparanase, metalloproteinases). | Loss of barrier function; impaired vasodilation; leukocyte adhesion. |

| Hormonal Decline (e.g. Estrogen) | Reduced synthesis of glycocalyx components; decreased nitric oxide signaling. | Increased permeability; pro-inflammatory endothelial phenotype. |

What Are the Therapeutic and Diagnostic Frontiers?

This glycocalyx-centric view of atherosclerosis opens new frontiers for both diagnosis and therapy. The measurement of circulating GCX fragments, such as syndecan-1 and hyaluronan, is an emerging area of clinical research, offering a potential direct biomarker of endothelial damage. Therapeutically, the focus shifts from simply lowering cholesterol to actively protecting and regenerating the GCX.

Strategies under investigation include supplementation with specific glycosaminoglycan precursors, therapies that inhibit shedding enzymes, and hormonal optimization protocols designed to support endothelial health at a fundamental level. For example, the known vasoprotective effects of estrogen are mediated in part by its ability to stimulate the synthesis of GCX components and enhance NO production. This academic framework reframes cardiovascular prevention, targeting the preservation of the endothelial glycocalyx as a primary therapeutic goal.

References

- Wulff, T. S. et al. “Apolipoprotein B modifies the association between lipoprotein(a) and ASCVD risk.” Atherosclerosis, vol. 392, 2024, pp. 1-7.

- Ridker, Paul M. “From C-Reactive Protein to Interleukin-6 to Interleukin-1 ∞ Moving Upstream To Identify Novel Targets for Atheroprotection.” Circulation Research, vol. 118, no. 1, 2016, pp. 145-56.

- Libby, Peter. “Inflammation in Atherosclerosis.” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, vol. 41, no. 1, 2021, pp. 111-12.

- Mach, François, et al. “2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias ∞ lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk.” European Heart Journal, vol. 41, no. 1, 2020, pp. 111-88.

- Reiss, AB, et al. “The Endothelial Glycocalyx in Atherosclerosis.” Current Medical Chemistry, vol. 24, no. 4, 2017, pp. 426-434.

- Pessentheiner, A.R. et al. “The role of the endothelial glycocalyx in health and disease.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Basis of Disease, vol. 1866, no. 10, 2020, p. 165839.

- Grundy, Scott M. et al. “2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 73, no. 24, 2019, pp. e285-e350.

- Krauss, Ronald M. “Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease risk ∞ a new era?” Journal of Internal Medicine, vol. 291, no. 4, 2022, pp. 411-413.

- Tsimikas, Sotirios. “A Test in Time ∞ Lipoprotein(a) and the Urgent Need for Universal Screening.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 79, no. 8, 2022, pp. 789-792.

- Shapiro, Michael D. et al. “ApoB, ApoA-I, and the risk of cardiovascular disease.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 6, no. 9, 2018, pp. 684-686.

Reflection

From Numbers to Narrative

You have now traveled from the familiar territory of a standard cholesterol test to the intricate, microscopic world of the endothelial glycocalyx. This knowledge does more than simply add new terms to your vocabulary. It fundamentally reframes your relationship with your own biology.

The numbers on a lab report cease to be static judgments of “good” or “bad.” Instead, they become data points in the unfolding narrative of your health, clues that point toward underlying processes within your unique physiological system. An elevated ApoB is a chapter about particle pressure; a high Lp(a) tells a story of genetic inheritance; a rising hs-CRP speaks of a body calling out in a state of low-grade alarm.

Understanding these deeper markers transforms you. You are no longer just a patient receiving results. You become an active investigator, a collaborator with your clinician in deciphering the language of your own body. This knowledge empowers you to ask more precise questions and to seek strategies that address the root causes of imbalance, not just the downstream symptoms.

The ultimate goal is a state of health that is not defined by the absence of disease, but by the presence of robust function and vitality. This journey of understanding is the first, most powerful step toward building a future where you are the author of your own well-being.

Glossary

cardiovascular risk

high-sensitivity c-reactive protein

atherogenic particles

systemic inflammation

each particle carries less cholesterol

insulin resistance

c-reactive protein

advanced biomarkers

metabolic syndrome

particle carries less cholesterol

more favorable lipid profile

endothelial glycocalyx