Fundamentals

Many individuals experience a subtle yet persistent shift in their physical and mental vitality as the years progress. Perhaps you have noticed a diminished capacity for recovery after physical exertion, a gradual accumulation of adipose tissue despite consistent effort, or a general sense of reduced vigor that was once a given.

These observations are not merely subjective feelings; they often reflect tangible changes within the body’s intricate biochemical systems. Understanding these shifts, particularly concerning hormonal balance, represents a significant step toward reclaiming optimal function and well-being.

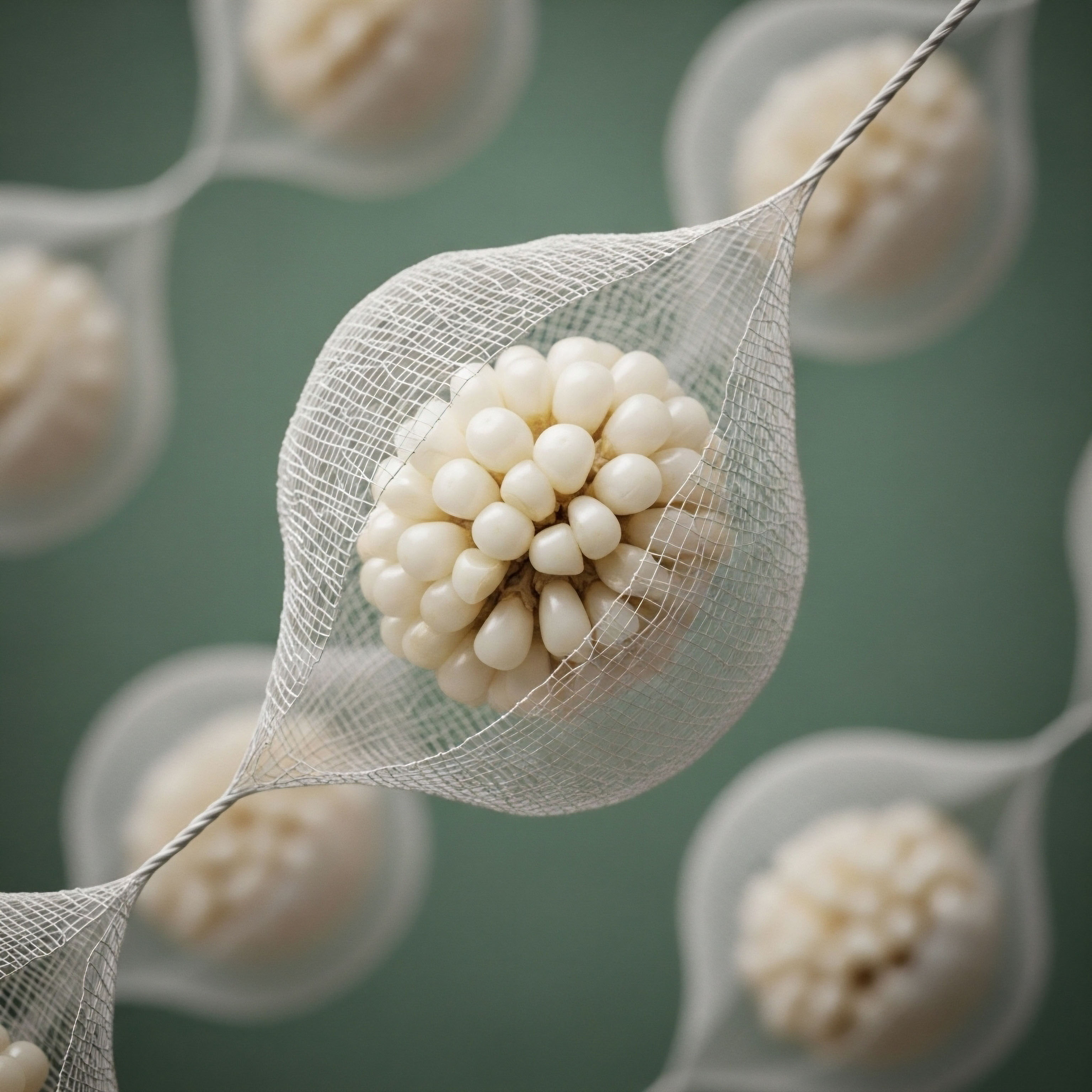

Among the various endocrine messengers, growth hormone (GH), also known as somatotropin, holds a central position in maintaining youthful physiology. Produced by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, a small but mighty structure at the base of the brain, GH orchestrates a wide array of processes.

Its influence extends to cellular repair, metabolic regulation, and the preservation of lean muscle mass. During childhood and adolescence, GH is instrumental in linear growth, but its role in adulthood transitions to tissue maintenance, body composition, and overall metabolic health.

The release of growth hormone occurs in a pulsatile fashion, meaning it is secreted in bursts rather than a continuous stream. These secretory episodes follow a circadian rhythm, with the most substantial pulses typically occurring during the initial phases of deep sleep. This nocturnal surge underscores the profound connection between restorative rest and the body’s capacity for repair and regeneration. Beyond sleep, other physiological states, such as intense physical activity and periods of nutritional deprivation, also stimulate GH release.

Growth hormone, a key endocrine messenger, is released in pulsatile bursts, primarily during deep sleep, influencing cellular repair and metabolic regulation.

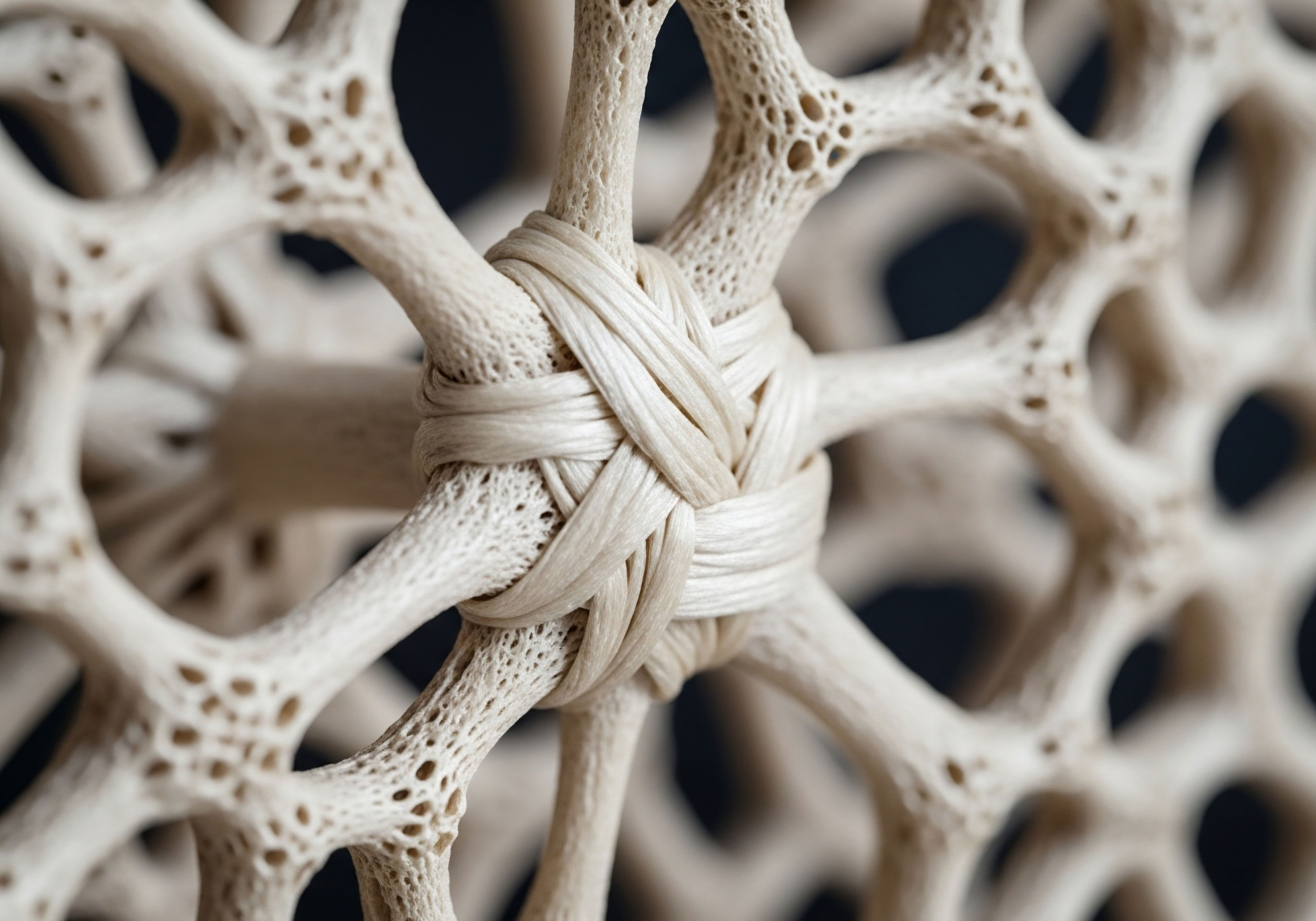

The regulation of GH secretion is a sophisticated feedback system involving the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and peripheral tissues. The hypothalamus, a control center in the brain, releases growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), which stimulates the pituitary to secrete GH. Conversely, the hypothalamus also produces somatostatin, a potent inhibitor that dampens GH release.

This delicate interplay ensures that GH levels are precisely modulated to meet the body’s dynamic needs. Nutritional strategies can influence this regulatory dance, offering avenues to support the body’s inherent capacity for GH production.

The Body’s Internal Messaging System

Consider the endocrine system as a complex communication network within the body. Hormones serve as the messages, traveling through the bloodstream to deliver instructions to various cells and organs. Growth hormone acts as a vital message, signaling cells to initiate repair processes, mobilize fat stores for energy, and synthesize new proteins for muscle tissue.

When this messaging system operates efficiently, the body maintains its structural integrity and metabolic vigor. When communication falters, the effects can manifest as the subtle symptoms of declining vitality that many individuals experience.

Understanding the foundational biology of growth hormone provides a framework for exploring how specific nutritional interventions can support its natural release. This approach moves beyond simplistic notions of “boosting” a single hormone, instead focusing on optimizing the entire system that governs its production and action. It is about recalibrating the body’s internal thermostat, allowing it to function closer to its inherent design.

Intermediate

Supporting the body’s intrinsic capacity for growth hormone release involves a thoughtful approach to nutritional strategies, moving beyond general dietary advice to consider specific macronutrients, amino acids, and meal timing. These elements interact with the complex regulatory mechanisms of the endocrine system, offering opportunities to enhance endogenous GH production. The goal is to create an internal environment conducive to optimal hormonal signaling, rather than attempting to force a physiological outcome.

Amino Acids and Their Hormonal Influence

Certain amino acids, the building blocks of protein, have demonstrated a direct influence on growth hormone secretion. Among these, arginine, ornithine, and glutamine stand out for their documented effects. Arginine, in particular, has been extensively studied for its ability to stimulate GH release. Its mechanism involves suppressing somatostatin, the inhibitory hormone that normally restricts GH secretion from the pituitary gland. By reducing this inhibitory signal, arginine effectively opens the floodgates for GH.

Research indicates that oral administration of arginine can lead to significant increases in GH levels. One study observed an eight-fold increase in GH from baseline after a single dose of an amino acid blend, with arginine being a key component. Another investigation found that a combination of arginine and lysine also provoked a release of pituitary somatotropin.

While the precise magnitude of response can vary among individuals, the principle remains ∞ providing specific amino acid precursors can modulate the body’s natural GH rhythms.

Ornithine, closely related to arginine, also plays a role in supporting GH release, often by being metabolized into arginine within the body. Its inclusion in nutritional protocols aims to further enhance the arginine pathway, contributing to a more robust GH response.

Glutamine, the most abundant amino acid in the body, has also been shown to increase plasma GH levels, even at relatively small doses. These amino acids are not merely supplements; they are biochemical signals that the body recognizes and utilizes to fine-tune its hormonal output.

Specific amino acids like arginine, ornithine, and glutamine can modulate growth hormone release by influencing inhibitory signals and providing essential precursors.

Macronutrient Timing and Endocrine Rhythms

The timing of macronutrient intake, particularly carbohydrates and proteins, exerts a significant influence on hormonal balance, including growth hormone secretion. High insulin levels, often a consequence of excessive or poorly timed carbohydrate consumption, are known to suppress GH release. This metabolic interplay highlights the importance of strategic eating patterns.

To support natural GH production, it is often recommended to avoid consuming large meals, especially those rich in carbohydrates, immediately before bedtime. The rationale is that a significant insulin spike at night can interfere with the natural nocturnal surge of growth hormone. Conversely, consuming protein-rich, low-carbohydrate snacks before sleep may provide the necessary amino acids without triggering an inhibitory insulin response.

Intermittent fasting, a dietary pattern that cycles between periods of eating and voluntary fasting, has also garnered attention for its potential to influence GH levels. During fasting periods, insulin levels decrease, and the body’s reliance on fat for fuel increases, both of which can create an environment conducive to elevated GH secretion.

Studies have shown that even short-term fasting can lead to substantial increases in growth hormone. This demonstrates how manipulating feeding windows can serve as a powerful lever for endocrine recalibration.

Optimizing Nutrient Intake for Growth Hormone Support

The following table outlines key nutritional strategies and their mechanisms for supporting growth hormone release:

| Nutritional Strategy | Primary Macronutrient Focus | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Amino Acid Supplementation | Protein (Arginine, Ornithine, Glutamine) | Reduces somatostatin inhibition, provides direct precursors for GH synthesis. |

| Strategic Meal Timing | Carbohydrates, Protein | Minimizes nocturnal insulin spikes, aligns with natural GH pulsatility. |

| Intermittent Fasting | Overall Caloric Intake | Lowers insulin, promotes fat utilization, creates a favorable metabolic state for GH. |

Beyond specific nutrients, the overall quality of one’s diet plays a foundational role. A diet rich in whole, unprocessed foods, adequate protein, healthy fats, and a diverse array of micronutrients provides the necessary building blocks and cofactors for optimal hormonal function. This comprehensive approach acknowledges that the body operates as an interconnected system, where no single nutrient or strategy exists in isolation.

How Does Sleep Quality Influence Growth Hormone Secretion?

The relationship between sleep and growth hormone is particularly compelling. The majority of daily GH secretion occurs during the deepest stages of sleep, specifically slow-wave sleep (SWS). This nocturnal release is critical for muscle repair, tissue regeneration, and metabolic regulation. Disrupted sleep patterns, insufficient sleep duration, or poor sleep quality can significantly impair this vital physiological process.

Chronic sleep deprivation can lead to lower overall GH levels, impacting the body’s ability to recover from daily stressors and physical activity. Conversely, prioritizing consistent, high-quality sleep can naturally enhance GH production, contributing to improved body composition, better recovery, and sustained energy levels. This highlights sleep not merely as a period of rest, but as an active phase of hormonal recalibration and physiological restoration.

Strategies to improve sleep quality, such as maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, creating a conducive sleep environment, and avoiding stimulants before bed, indirectly support growth hormone release. These lifestyle interventions are integral to any comprehensive approach aimed at optimizing endocrine function.

Academic

A deeper understanding of nutritional strategies supporting natural growth hormone release necessitates an exploration of the intricate neuroendocrine axes and cellular signaling pathways involved. The regulation of growth hormone (GH) is a testament to the body’s sophisticated homeostatic mechanisms, involving a dynamic interplay between hypothalamic peptides, pituitary somatotrophs, and peripheral feedback loops. This systems-biology perspective reveals how dietary components can subtly yet profoundly influence these complex biological circuits.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Somatotropic Axis

The primary control of GH secretion resides within the hypothalamic-pituitary-somatotropic (HPS) axis. The hypothalamus, a key brain region, acts as the central orchestrator, releasing two principal neurohormones ∞ growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) and somatostatin (also known as growth hormone-inhibiting hormone, GHIH).

GHRH stimulates the synthesis and release of GH from the somatotroph cells of the anterior pituitary gland, while somatostatin exerts a potent inhibitory effect. The pulsatile nature of GH secretion arises from the rhythmic fluctuations in the release of these two opposing hypothalamic signals.

Peripheral feedback also plays a critical role. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), primarily produced in the liver in response to GH stimulation, provides negative feedback to both the hypothalamus and the pituitary, reducing GHRH release and directly inhibiting GH secretion. This multi-layered regulatory system ensures tight control over circulating GH levels, preventing both deficiency and excess.

Nutrient Sensing and Hormonal Modulation

Nutritional status directly impacts the HPS axis. Periods of fasting or caloric restriction, for instance, are known to increase GH secretory burst frequency and amplitude. This adaptive response helps preserve lean body mass and mobilize fat stores during times of energy scarcity. The underlying mechanisms involve alterations in both GHRH and somatostatin secretion, with fasting potentially increasing GHRH activity and prolonging the nadirs of somatostatin.

The role of specific macronutrients is also significant. High carbohydrate intake, particularly simple sugars, leads to rapid increases in blood glucose and subsequent insulin release. Insulin, being an anabolic hormone, tends to suppress GH secretion. This antagonism is a critical consideration for nutritional timing. Conversely, protein and certain amino acids can stimulate GH release.

Consider the influence of ghrelin, often termed the “hunger hormone,” which is predominantly secreted by the stomach. Ghrelin acts as an endogenous ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R), directly stimulating GH release from the pituitary somatotrophs and synergizing with GHRH.

Ghrelin levels typically rise before meals and fall after food consumption, with carbohydrates and proteins having a greater suppressive effect than fats. This highlights a fascinating gastrointestinal-pituitary axis, where the state of the digestive system directly communicates with the endocrine system to influence GH dynamics.

The HPS axis, regulated by GHRH and somatostatin, is profoundly influenced by nutrient sensing, with fasting and specific amino acids stimulating GH release, while high insulin levels suppress it.

Amino Acid Mechanisms of Growth Hormone Release

The stimulatory effect of certain amino acids on GH release is a subject of ongoing research. Arginine, for example, is thought to act by attenuating the release or action of somatostatin. This reduction in somatostatin’s inhibitory tone allows for greater GHRH-mediated GH secretion. Additionally, arginine may directly stimulate pituitary cells by increasing intracellular calcium influx.

The combined administration of arginine and ornithine has shown synergistic effects, likely due to ornithine’s conversion to arginine within the urea cycle, thereby increasing arginine bioavailability. Glutamine’s mechanism is less clear but may involve its role in cellular energy metabolism or its influence on neurotransmitter systems that indirectly affect GH regulation.

The following list summarizes key amino acids and their proposed mechanisms in supporting GH release:

- Arginine ∞ Reduces somatostatin inhibition, potentially directly stimulates pituitary somatotrophs.

- Ornithine ∞ Acts as a precursor to arginine, enhancing its bioavailability and subsequent GH-stimulating effects.

- Glutamine ∞ May influence GH levels through metabolic pathways or indirect neuroendocrine modulation.

The interplay between these amino acids and the broader metabolic landscape is complex. For instance, the presence of other macronutrients, particularly carbohydrates, can blunt the GH response to amino acid supplementation due to insulin’s suppressive effect. This underscores the importance of consuming these amino acids in a fasted state or strategically timed around periods of low insulin.

The Circadian Clock and Metabolic Synchronization

The pulsatile secretion of GH is tightly coupled with the body’s circadian rhythms, particularly the sleep-wake cycle. The most prominent GH pulse occurs shortly after the onset of deep, slow-wave sleep. This nocturnal surge is not merely coincidental; it represents a critical period for tissue repair, protein synthesis, and fat metabolism. Disruptions to this natural rhythm, such as chronic sleep deprivation or irregular sleep patterns, can significantly impair GH secretion.

The intricate relationship between sleep and GH is further complicated by the reciprocal influence of other hormones. For example, cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone, typically declines during the early stages of sleep, creating a permissive environment for GH release. Elevated cortisol levels, often associated with chronic stress or poor sleep, can suppress GH. This highlights the interconnectedness of stress management, sleep hygiene, and hormonal balance.

The table below illustrates the impact of sleep stages on hormonal activity:

| Sleep Stage | Primary Hormonal Activity | Impact on Growth Hormone |

|---|---|---|

| Slow-Wave Sleep (Deep Sleep) | Peak Growth Hormone Release, Cortisol Decline | Maximal GH secretion, crucial for repair and regeneration. |

| REM Sleep (Rapid Eye Movement) | Testosterone Production (in men), Melatonin Influence | Indirectly supports overall hormonal balance, less direct GH release. |

| Light Sleep | Transitional Phase | Minimal direct GH release, prepares for deeper stages. |

Understanding these deep physiological connections allows for a more holistic and effective approach to supporting natural growth hormone release. It moves beyond isolated interventions to consider the entire symphony of biological processes that contribute to vitality and function. The goal is to harmonize these systems, allowing the body to perform at its inherent best.

References

- Isidori, A. Lo Monaco, A. & Cappa, M. (1981). A study of growth hormone release in man after oral administration of amino acids. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 7(7), 475-481.

- Suryawan, A. et al. (2020). Increased Human Growth Hormone After Oral Consumption of an Amino Acid Supplement ∞ Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Crossover Study in Healthy Subjects. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(4), 1082-1090.

- Arvat, E. et al. (2022). Growth Hormone Response to L-Arginine Alone and Combined with Different Doses of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(23), 14940.

- Kojima, M. et al. (1999). Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature, 402(6762), 656-660.

- Van Cauter, E. & Copinschi, G. (2000). Perspectives in research on growth hormone and sleep. Sleep, 23(Suppl 4), S147-S151.

- Zajac, A. et al. (2010). Arginine and ornithine supplementation increases growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 serum levels after heavy-resistance exercise in strength-trained athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(4), 1082-1090.

- Chapman, I. M. et al. (2005). Evidence for acyl-ghrelin modulation of growth hormone release in the fed state. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(11), 6028-6035.

- Takahashi, Y. et al. (1968). Growth hormone secretion during sleep. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 47(9), 2079-2090.

- Rasmussen, M. H. et al. (1995). The effect of 2 days of fasting on the pulsatile secretion of growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor I, and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 in healthy subjects. Metabolism, 44(12), 1594-1601.

- Ho, K. K. et al. (1988). Effects of somatostatin on growth hormone-releasing hormone-induced growth hormone secretion in man. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 67(6), 1186-1189.

Reflection

The journey toward understanding your own biological systems is a deeply personal one, often beginning with a subtle awareness that something feels misaligned. The insights shared here regarding nutritional strategies and growth hormone are not prescriptive mandates, but rather invitations to consider the profound influence of daily choices on your internal landscape.

Each individual’s endocrine system operates with unique sensitivities and responses, shaped by genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors. The information presented serves as a guide, illuminating the pathways through which you can consciously support your body’s inherent wisdom.

True vitality is not found in chasing fleeting trends or quick fixes, but in the consistent, informed application of principles that honor your physiology. As you contemplate these strategies, consider them as tools for self-discovery, allowing you to observe how your body responds and adapts.

This ongoing dialogue with your biological systems is where genuine and lasting well-being takes root. The knowledge you have gained is merely the initial step; the subsequent steps involve a thoughtful, personalized application that respects your unique biological blueprint.