Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t touch. A subtle shift in your mood, your energy, your body’s internal rhythm. You might notice changes in your weight, your skin, or your libido.

These experiences are not just in your head; they are real, tangible signals from deep within your body’s command center ∞ the endocrine system. This intricate network of glands communicates using chemical messengers called hormones, dictating everything from your metabolic rate to your stress response. Understanding this system is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

Your endocrine system is a highly sophisticated communication network, responsible for maintaining equilibrium across all of your biological functions. Think of it as an internal postal service, where hormones are the letters, glands are the post offices, and your cells are the recipients, each with a specific mailbox or receptor.

For this service to run efficiently, it requires specific raw materials. These materials are not exotic; they are the essential micronutrients ∞ vitamins and minerals ∞ that your body must obtain from your diet. Without them, the entire system falters. Hormone production slows, messages get lost, and the symptoms you feel are the direct result of this communication breakdown.

The endocrine system’s function is entirely dependent on a consistent supply of specific vitamins and minerals that act as the foundational elements for hormone production and signaling.

The Building Blocks of Hormonal Health

Every hormone your body produces has a unique molecular structure, and its synthesis depends on a precise sequence of biochemical reactions. Micronutrients are the non-negotiable participants in these reactions. They act as cofactors for enzymes, the catalysts that drive hormone creation. A deficiency in even one of these critical elements can create a bottleneck, disrupting an entire hormonal cascade.

Key Micronutrients for Endocrine Function

Several micronutrients are particularly important for maintaining a healthy endocrine system. Their roles are distinct yet interconnected, highlighting the system’s complexity.

- Iodine This mineral is a direct component of thyroid hormones, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). The thyroid gland, located in your neck, sets the metabolic pace for your entire body. Without sufficient iodine, the thyroid cannot produce these hormones, leading to a condition known as hypothyroidism, characterized by fatigue, weight gain, and cold intolerance.

- Selenium A crucial partner to iodine, selenium is required for the activity of enzymes called deiodinases. These enzymes are responsible for converting the less active T4 hormone into the more potent T3 hormone in your tissues. Selenium also has a protective antioxidant role within the thyroid gland itself.

- Zinc This mineral is a powerhouse for endocrine health, involved in the function of the pituitary gland, the “master gland” that directs other endocrine organs. Zinc is essential for the synthesis of testosterone and plays a role in insulin regulation. A deficiency can manifest as low libido, poor immune function, or impaired glucose metabolism.

- Magnesium Often called the “relaxation mineral,” magnesium is involved in over 300 enzymatic reactions, including those that regulate the stress response. It helps modulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, our central stress response system, and influences the sensitivity of our cells to insulin. Chronic stress can deplete magnesium levels, creating a cycle of imbalance.

- Vitamin D Functioning more like a pro-hormone than a vitamin, Vitamin D is a steroid hormone precursor. This means it is the raw material from which other hormones, including testosterone, are made. Its receptors are found on cells throughout the body, indicating its wide-ranging influence on immune function, mood, and hormonal regulation.

- B Vitamins This family of vitamins, particularly B5 (pantothenic acid) and B6, are critical for the production of adrenal hormones like cortisol and sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone. They are also fundamental to the energy production processes within every cell, which is necessary to fuel hormonal synthesis.

Your body’s hormonal balance is a direct reflection of its nutritional status. The symptoms of hormonal imbalance are often the body’s way of communicating a deeper need for these essential micronutrients. By understanding their roles, you can begin to see your health not as a series of disconnected problems, but as an interconnected system that you have the power to support and recalibrate.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond the foundational knowledge of which micronutrients are important, we can examine the direct, functional relationships between nutrient status and the clinical protocols used to optimize hormonal health. The effectiveness of therapies like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or thyroid support is not determined in a vacuum. The body’s underlying biochemical environment, rich or poor in specific micronutrients, can significantly influence outcomes. These elements are not passive bystanders; they are active participants in hormone synthesis, transport, and receptor sensitivity.

Micronutrient Sufficiency in Clinical Protocols

When undertaking a hormonal optimization protocol, ensuring adequate levels of key micronutrients is a primary step. A protocol’s success can be amplified or hindered by the availability of these cofactors. For instance, administering testosterone to a man with a significant zinc deficiency may yield suboptimal results, as zinc is intrinsically involved in how the body utilizes testosterone.

How Does Zinc Status Affect TRT Outcomes?

Zinc’s role in male hormonal health extends beyond simple testosterone production. It is involved in multiple stages of the androgen pathway. The pituitary gland requires zinc for the synthesis and release of Luteinizing Hormone (LH), the primary signal that tells the testes to produce testosterone.

Even in the context of exogenous testosterone administration via TRT, zinc remains important. It influences the androgen receptors found on cells throughout the body, potentially affecting how tissues respond to the circulating testosterone. Furthermore, zinc helps to inhibit the activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone into estrogen. Maintaining adequate zinc levels can therefore be a supportive measure in managing the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio, a key goal in many TRT protocols.

The body’s ability to effectively utilize and balance hormones from therapeutic protocols is directly linked to its internal reserve of essential mineral and vitamin cofactors.

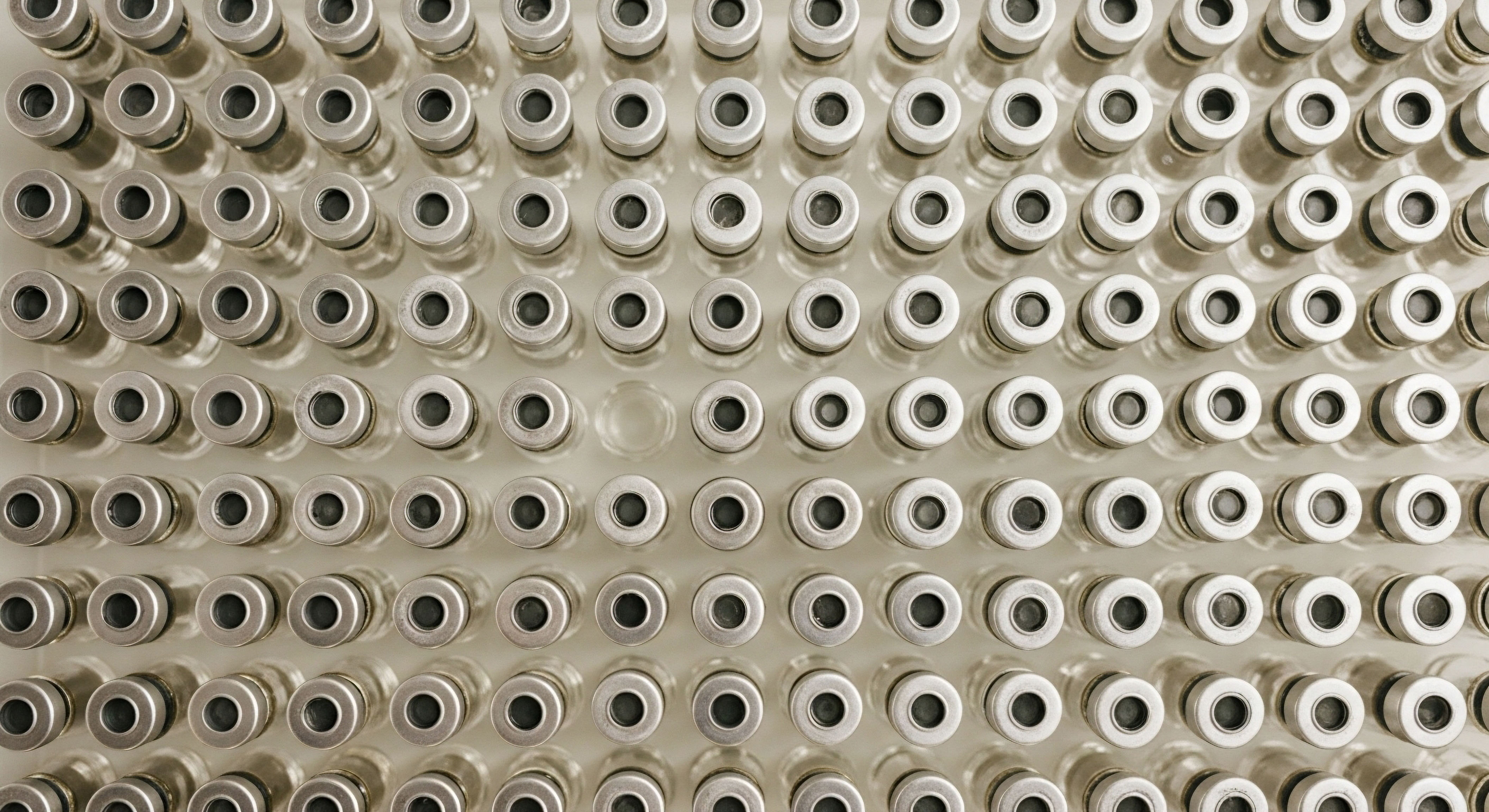

The following table outlines the specific roles of key micronutrients in relation to common hormonal health concerns and therapies, providing a clearer picture of their clinical relevance.

| Micronutrient | Primary Endocrine Role | Relevance to Clinical Protocols | Common Deficiency Signs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Testosterone synthesis; LH production; Aromatase inhibition. | Supports efficacy of TRT; helps manage estrogen conversion. | Low libido, impaired immunity, hair loss, poor wound healing. |

| Selenium | Conversion of T4 to active T3; Thyroid gland protection. | Essential for patients on thyroid medication (T4-only); supports overall metabolic rate. | Fatigue, brain fog, hair loss, muscle weakness. |

| Magnesium | HPA axis regulation; Insulin sensitivity; Cofactor for Vitamin D activation. | Helps manage stress response (cortisol); improves metabolic parameters; supports TRT and peptide therapy goals. | Muscle cramps, anxiety, poor sleep, insulin resistance. |

| Vitamin D | Steroid hormone precursor; Androgen receptor expression. | Foundational for all steroid hormone therapies (TRT); influences testosterone levels. | Fatigue, bone pain, depression, frequent infections. |

| Iodine | Direct component of thyroid hormones (T4 and T3). | Critical for thyroid hormone production; deficiency must be corrected for thyroid protocols to be effective. | Fatigue, weight gain, goiter (enlarged thyroid), cold intolerance. |

The Synergistic Web of Micronutrients

Micronutrients rarely work in isolation. Their functions are deeply interconnected, creating a web of dependencies. A prime example is the relationship between Vitamin D, magnesium, and calcium. Vitamin D is essential for calcium absorption, but magnesium is required to convert Vitamin D into its active form in the body.

A person could be supplementing with Vitamin D and still not reap its full benefits if they have a concurrent magnesium deficiency. This highlights the importance of a comprehensive approach to nutritional status when evaluating and implementing hormonal therapies.

Assessing Micronutrient Status

Understanding your personal micronutrient levels is a key piece of the puzzle. Standard serum blood tests can provide some information, but they may not always tell the whole story. For example, serum magnesium represents less than 1% of the body’s total magnesium, and levels can appear normal even when an intracellular deficiency exists.

More advanced testing, such as red blood cell (RBC) mineral analysis, can offer a more accurate picture of the body’s functional stores. Working with a knowledgeable clinician to interpret these labs is essential for creating a targeted and effective supplementation strategy.

The table below provides a brief overview of different supplemental forms of a key mineral, magnesium, illustrating that the choice of supplement can be as important as the decision to supplement in the first place.

| Form of Magnesium | Primary Characteristics | Common Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Glycinate | Highly bioavailable; bound to the amino acid glycine, which has calming properties. | Often used for improving sleep quality, reducing anxiety, and general repletion without causing digestive upset. |

| Magnesium Citrate | Good bioavailability; citrate form can have a mild laxative effect. | Used for general repletion and to support regular bowel movements. |

| Magnesium L-Threonate | Shown to effectively cross the blood-brain barrier. | Specifically targeted for supporting cognitive function, memory, and brain health. |

| Magnesium Oxide | Lower bioavailability; higher elemental magnesium content but poorly absorbed. | Commonly found in lower-quality supplements; primarily used as a laxative. |

By understanding these more detailed interactions, you can move from a general awareness of nutrition to a specific, actionable strategy. This knowledge empowers you to engage in a more informed dialogue with your healthcare provider, ensuring that your hormonal health protocol is built on the strongest possible biochemical foundation.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of endocrine function requires moving beyond a simple inventory of micronutrients and their corresponding hormones. The focus must shift to the molecular mechanisms through which these elements govern the intricate signaling pathways that define hormonal homeostasis. A deep exploration of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis provides a compelling case study.

This axis represents a complex, multi-tiered feedback loop that regulates reproductive function and steroidogenesis in both men and women. The integrity and efficiency of this system are fundamentally dependent on the presence of specific micronutrients that act at critical enzymatic and genomic checkpoints.

Molecular Endocrinology of the HPG Axis

The HPG axis is initiated in the hypothalamus with the pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). GnRH travels to the anterior pituitary, where it stimulates the secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins then act on the gonads (testes in men, ovaries in women) to stimulate sex hormone production ∞ primarily testosterone and estrogen ∞ and gametogenesis.

The circulating sex hormones, in turn, exert negative feedback on both the hypothalamus and the pituitary to suppress GnRH and gonadotropin release, thus completing the regulatory loop. Micronutrients are not merely supportive of this process; they are integral to its molecular machinery.

What Is the Genomic Role of Zinc in Androgen Signaling?

Zinc’s influence on the HPG axis is a prime example of a micronutrient’s deep mechanistic role. Its most critical function may lie in its structural contribution to nuclear receptors. Androgen receptors (AR), which bind testosterone and its potent metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT), are transcription factors that regulate gene expression.

The DNA-binding domain of the AR contains two “zinc finger” motifs. These are structural domains where a zinc ion is coordinated by cysteine residues, creating a finger-like projection that fits into the major groove of DNA. This physical interaction is an absolute prerequisite for the androgen receptor to bind to specific DNA sequences known as hormone response elements (HREs) and initiate the transcription of androgen-dependent genes.

Therefore, a deficiency in zinc can directly impair the ability of target tissues ∞ muscle, bone, brain ∞ to respond to testosterone, regardless of how much testosterone is circulating in the bloodstream. This explains why symptoms of hypogonadism can persist in individuals with seemingly normal testosterone levels if their zinc status is compromised.

From a clinical perspective, this underscores the necessity of evaluating zinc status as a primary step in addressing androgen deficiency, as correcting a deficiency may restore endogenous signaling without immediate recourse to exogenous hormone administration.

Micronutrients function as essential molecular switches and structural components within the endocrine system, directly enabling or disabling hormone synthesis, signaling, and genetic expression.

The following list details the specific biochemical and genomic actions of key micronutrients within the context of the HPG axis and steroidogenesis.

- Vitamin D ∞ The Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) is expressed in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and testes. Studies indicate that the active form of Vitamin D, calcitriol, can upregulate the expression of genes involved in testosterone synthesis. Furthermore, VDR can form a heterodimer with the Retinoid X Receptor (RXR), and this complex can influence the expression of genes regulated by other steroid hormones, demonstrating significant crosstalk between signaling pathways.

- Selenium ∞ The testes have a high concentration of selenium, primarily incorporated into selenoproteins like Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx). During steroidogenesis, significant oxidative stress is generated. GPx is a powerful antioxidant enzyme that neutralizes reactive oxygen species, thereby protecting Leydig cells (the site of testosterone production) from oxidative damage and preserving their functional capacity. Selenium deficiency can lead to increased oxidative stress, impaired Leydig cell function, and reduced testosterone output.

- Boron ∞ This trace mineral, while less discussed, has been shown in some studies to influence steroid hormone metabolism. Research suggests boron can decrease levels of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), a protein that binds to testosterone and renders it inactive. By reducing SHBG, boron may increase the concentration of free, biologically active testosterone.

Interplay between Endocrine and Metabolic Pathways

The endocrine system does not operate in isolation from the body’s broader metabolic state. Insulin resistance, a condition where cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin, has profound implications for the HPG axis.

Elevated insulin levels, common in insulin resistance, can disrupt the pulsatile release of GnRH from the hypothalamus and may also increase aromatase activity, leading to a higher conversion of testosterone to estrogen. Magnesium plays a critical role at this intersection.

It is a vital cofactor for enzymes in the insulin signaling cascade, including tyrosine kinase at the insulin receptor level. Adequate magnesium status is associated with improved insulin sensitivity. By supporting proper insulin function, magnesium indirectly supports the healthy functioning of the HPG axis, preventing the downstream hormonal disruptions caused by metabolic dysfunction.

This systems-biology perspective reveals that addressing hormonal imbalances often requires looking “upstream” at the metabolic and nutritional factors that govern the entire regulatory network. A purely hormonal intervention may fail if the underlying biochemical environment is not conducive to its success. The sophisticated clinician understands that micronutrient optimization is a foundational element of any robust and sustainable endocrine protocol.

References

- Ventura, Marco, et al. “Selenium and Thyroid Disease ∞ From Pathophysiology to Treatment.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2017, 2017, pp. 1-9.

- Prasad, Ananda S. “Zinc in Human Health ∞ Effect of Zinc on Immune Cells.” Molecular Medicine, vol. 14, no. 5-6, 2008, pp. 353-57.

- Pilz, S. et al. “Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Testosterone Levels in Men.” Hormone and Metabolic Research, vol. 43, no. 3, 2011, pp. 223-25.

- Kopp, W. “How Western Diet And Lifestyle Drive The Pandemic Of Obesity And Civilization Diseases.” Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity ∞ Targets and Therapy, vol. 12, 2019, pp. 2221-2236.

- DiNicolantonio, James J. and James H. O’Keefe. “Magnesium and Vitamin D Deficiency as a Potential Cause of Insulin Resistance, Hypertension, and Endothelial Dysfunction.” Postgraduate Medicine, vol. 130, no. 2, 2018, pp. 234-245.

- Fallah, A. et al. “Zinc is an Essential Element for Male Fertility ∞ A Review of Roles in Men’s Health, Germination, Sperm Quality, and Fertilization.” Journal of Reproduction & Infertility, vol. 19, no. 2, 2018, pp. 69-81.

- Schöne, F. et al. “The new German iodine-monitoring-system and the role of selenium for thyroid-hormone-metabolism.” Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, vol. 20, no. 4, 2006, pp. 227-34.

- Barbagallo, Mario, and Ligia J. Dominguez. “Magnesium and Type 2 Diabetes.” World Journal of Diabetes, vol. 6, no. 10, 2015, pp. 1152-57.

- Holick, Michael F. “Vitamin D Deficiency.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 357, no. 3, 2007, pp. 266-81.

- Köhrle, Josef. “The trace element selenium and the thyroid gland.” Biochimie, vol. 81, no. 5, 1999, pp. 527-33.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

You have now journeyed through the intricate world of micronutrients and their profound connection to your body’s hormonal symphony. This knowledge is more than a collection of scientific facts; it is a new lens through which to view your own lived experience.

The fatigue, the mood shifts, the physical changes ∞ these are not random occurrences but data points, signals from a system requesting the specific tools it needs to function optimally. You are the foremost expert on your own body, and this understanding of its inner workings is the first, most powerful step toward becoming an active participant in your own health narrative.

This exploration is not an end point. It is an invitation. An invitation to look deeper, to ask more precise questions, and to seek a partnership with a clinician who recognizes that your symptoms are valid and that your biology is unique.

The path to reclaiming your vitality is a personal one, built on the foundation of self-knowledge and guided by precise, individualized clinical strategies. The journey forward is about moving from understanding the system to intelligently calibrating your own.