Fundamentals

You may feel it as a persistent fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch, or perhaps it manifests as a subtle but unshakeable sense of anxiety. It could be the frustration of seeing your body composition change despite consistent effort with diet and exercise.

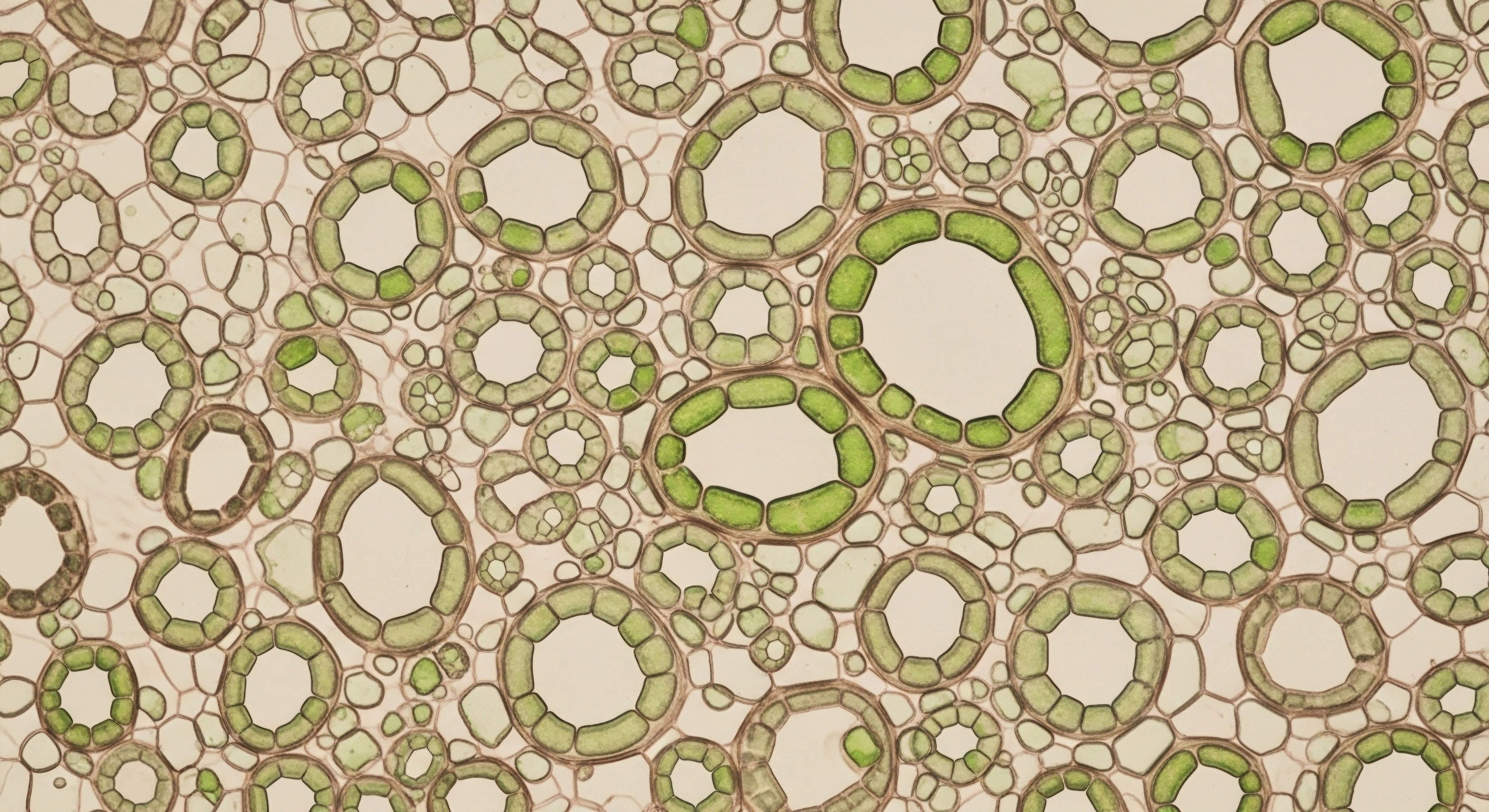

These experiences are valid, and they are your body’s way of communicating a deeper story. Your biology is speaking through a complex chemical language, and the words in that language are metabolites. These small molecules are the end products of metabolism, the intricate process of converting food into energy and building blocks for your cells. They represent a real-time snapshot of your body’s internal state, reflecting how well your systems are functioning, communicating, and adapting.

Understanding this language is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. Your hormonal and metabolic systems are profoundly interconnected. Think of your hormones as conductors of a grand orchestra, directing countless bodily functions. Metabolites are the notes produced by the instruments, revealing the quality of the performance. When the hormonal signals are clear and balanced, the metabolic music is harmonious. When the signals become distorted, the resulting metabolic profile can indicate rising health risks long before a formal diagnosis appears.

Metabolites are the chemical footprints that reveal the operational status of your body’s most critical systems.

The Central Role of Insulin

One of the most significant narratives told by your metabolic profile revolves around insulin. Insulin’s primary role is to transport glucose from your bloodstream into your cells, where it is used for energy. In a state of health, this process is seamless and efficient.

A condition known as insulin resistance develops when your cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals. This prompts your pancreas to produce even more insulin to overcome the resistance, leading to elevated levels of both insulin and glucose in the blood. This state is a primary indicator of metabolic dysfunction.

The symptoms are often subtle at first. You might experience persistent cravings for carbohydrates, a slump in energy after meals, or find it increasingly difficult to lose weight, especially around the abdomen. These are direct physiological responses to your body struggling to manage its energy supply.

Elevated insulin acts as a powerful signal for fat storage, making weight management a challenging endeavor. The fatigue you feel is a genuine energy crisis at the cellular level; your cells are starved for the glucose that remains locked in your bloodstream.

Cortisol and the Stress Connection

Another key metabolite story is written by cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. Produced in response to perceived threats, cortisol is designed to prepare your body for immediate action. In modern life, stressors are often chronic, leading to persistently elevated cortisol levels. This sustained output has significant metabolic consequences.

Cortisol can directly interfere with insulin signaling, promoting insulin resistance. It also stimulates the breakdown of muscle protein to create glucose, further elevating blood sugar levels and placing additional strain on your system.

This biochemical state often translates into tangible feelings of being ‘wired and tired.’ You might struggle with poor sleep quality, feel anxious or irritable, and notice an increase in abdominal fat. High cortisol levels are biochemically linked to cravings for high-fat, high-sugar foods, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of stress and metabolic imbalance.

Your body, interpreting chronic stress as a persistent danger, is attempting to store energy for a crisis that never arrives. Understanding the metabolites associated with insulin and cortisol provides a powerful lens through which to view your symptoms, connecting your lived experience to precise biological mechanisms.

Intermediate

As we look deeper into the metabolic conversation happening within your body, we move beyond the primary signals of insulin and cortisol to the more detailed messages carried by specific families of metabolites. These molecules tell a story not just about your present state, but about the trajectory of your health.

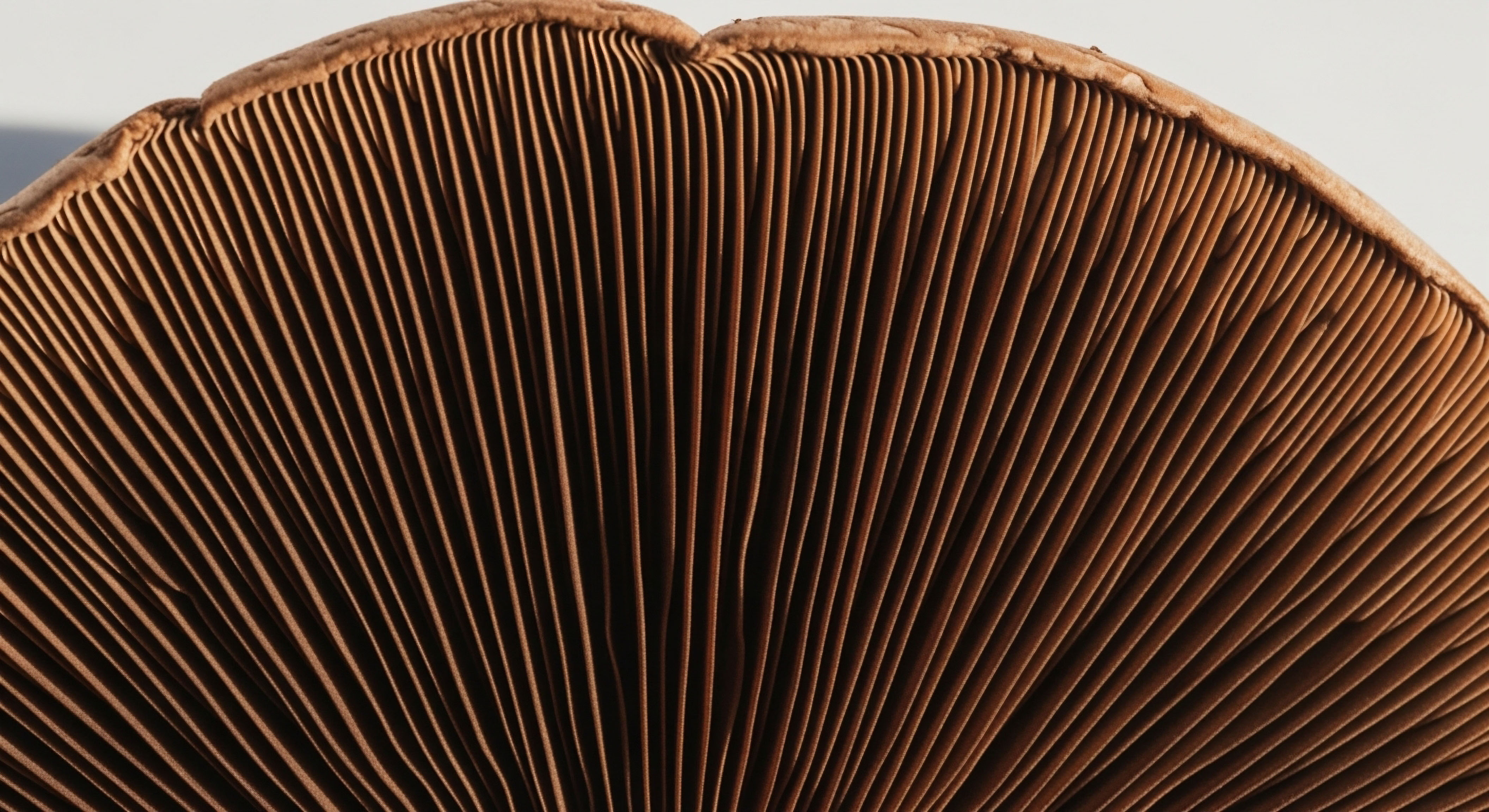

One of the most revealing of these stories comes from how your body processes sex hormones, particularly estrogen. The way your body metabolizes and eliminates estrogen creates distinct metabolites that have very different effects on your tissues, offering profound insight into your hormonal health and potential risks.

The liver is the primary site for this metabolic process, breaking down parent estrogens into several downstream metabolites through a series of detoxification phases. The balance between these metabolites is a critical indicator of your body’s ability to maintain hormonal equilibrium.

An imbalance can manifest in symptoms like heavy or painful periods, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), bloating, mood swings, and low libido, all of which suggest that the detoxification pathways may not be functioning optimally. Examining these specific metabolites offers a more refined understanding of your hormonal landscape.

The Estrogen Metabolite Ratio

The breakdown of estrogen primarily follows three major pathways, resulting in three key types of metabolites. The balance among these pathways is a significant indicator of health.

- 2-Hydroxyestrone (2-OH) This is often referred to as the ‘protective’ or ‘favorable’ estrogen metabolite. It has a weak estrogenic effect and is associated with healthy cell cycles and a lower risk profile for estrogen-sensitive tissues. Optimal levels of 2-OH suggest that your body’s Phase I liver detoxification is functioning efficiently.

- 16-alpha-Hydroxyestrone (16α-OH) This metabolite has a much stronger estrogenic effect. It promotes cell proliferation and is associated with symptoms of estrogen dominance, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and breast tenderness. Elevated levels of 16α-OH relative to 2-OH can indicate an increased risk profile.

- 4-Hydroxyestrone (4-OH) This metabolite is considered the most potentially harmful. While it has a weak estrogenic effect, its chemical structure allows it to interact with DNA, potentially causing damage if it is not efficiently cleared by Phase II detoxification pathways. Elevated 4-OH levels are a significant concern and point to a need to support the body’s antioxidant and detoxification systems.

The ratio of 2-OH to 16α-OH is a commonly used clinical marker. A higher ratio is generally desirable, reflecting a metabolic preference for the protective pathway. This balance is not static; it is influenced by diet, lifestyle, and gut health. For instance, the gut microbiome contains a collection of bacteria known as the estrobolome, which produces enzymes that can reactivate estrogens that were meant for excretion, thereby influencing circulating levels and metabolite patterns.

The ratio of estrogen metabolites provides a clear window into how your body is managing its hormonal burden.

Metabolites and Personalized Hormone Protocols

Understanding an individual’s unique metabolite profile is fundamental to designing effective and safe hormonal optimization protocols. Simply measuring parent hormones like testosterone or estradiol provides only part of the picture. The true therapeutic precision comes from understanding how an individual’s body processes these hormones.

For a man on Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), monitoring estrogen metabolites is critical. The therapeutic testosterone can be converted into estrogen via the aromatase enzyme. If this estrogen is then preferentially metabolized down the 4-OH or 16α-OH pathways, it could create unintended risks. The use of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole is designed to manage this conversion, but understanding the downstream metabolite profile ensures a more complete level of safety and efficacy.

For a woman considering or using hormone therapy, this information is even more critical. A protocol involving Testosterone Cypionate and Progesterone can be tailored based on her unique metabolic signature. If her profile shows a tendency toward the more proliferative 16α-OH pathway, the protocol might be adjusted, or additional nutritional and lifestyle support for liver detoxification might be emphasized.

This level of personalization moves beyond simply replacing a number on a lab report; it is about restoring systemic balance and ensuring the therapy promotes long-term wellness.

| Metabolite Class | Specific Indicator | Associated Health Risk | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Metabolites | Low 2-OH / 16α-OH Ratio | Increased estrogenic burden, potential for proliferative tissue changes. | Guides hormone therapy, suggests need for liver and gut support. |

| Estrogen Metabolites | Elevated 4-OH Estrone | Potential for DNA damage if not properly detoxified. | Indicates need for enhanced Phase II detoxification and antioxidant support. |

| Glucose Metabolism | Elevated Fasting Insulin | Insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, increased risk for type 2 diabetes. | Monitors effectiveness of lifestyle changes and therapies like peptide protocols. |

| Lipid Metabolites | Elevated Triglycerides | Cardiovascular disease risk, often linked to insulin resistance. | Key marker for assessing overall metabolic health and response to therapy. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of health risk requires a departure from single-marker assessments toward a systems-biology perspective. The metabolome, a comprehensive profile of small-molecule metabolites, offers a functional readout of an individual’s phenotype, reflecting the complex interplay between genetics, environment, and physiology.

Within this framework, specific metabolites serve as critical nodes in biochemical networks, and their dysregulation can signal pathogenic processes long before clinical disease manifestation. The administration of exogenous hormones, as in Hormone Therapy (HT), provides a powerful model for understanding these dynamics, as it introduces a significant perturbation to the endocrine system, revealing the downstream metabolic consequences and their association with long-term health outcomes, such as coronary heart disease (CHD).

How Does Hormone Therapy Alter Metabolomic Profiles?

Research, such as the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), has provided invaluable data by measuring metabolomic profiles in postmenopausal women undergoing different HT regimens. These studies reveal that different forms of HT create distinct metabolic signatures. For example, treatment with conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) alone produces a different set of changes in the metabolome compared to CEE combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA).

This distinction is vital, as it suggests that the addition of a progestin modifies the metabolic effects of estrogen, which may in turn mediate the different health outcomes observed between these therapies.

The primary classes of metabolites affected include lipids, amino acids, and acylcarnitines. Specifically, CEE therapy has been shown to cause significant alterations in triacylglycerols and acylcarnitines, which are molecules central to fatty acid transport and oxidation.

The fact that some of these changes are unique to the CEE-only group, while others are specific to the CEE+MPA group, underscores the principle that different hormonal inputs produce unique systemic responses. This level of detail is paramount for moving toward truly personalized medicine, where therapeutic choices are informed by a deep understanding of an individual’s metabolic tendencies.

Different hormone therapy formulations create unique metabolic fingerprints, directly influencing their long-term risk profiles.

Acylcarnitines and Triacylglycerols as Risk Mediators

The specific metabolites that are altered by HT and also associated with CHD risk provide a mechanistic link between the therapy and the outcome. Acylcarnitines are intermediates in the transport of fatty acids into the mitochondria for beta-oxidation. An altered acylcarnitine profile can indicate mitochondrial dysfunction and inefficient energy production, a state that is increasingly recognized as a contributor to cardiovascular pathology.

Triacylglycerols (triglycerides) are a well-established biomarker for cardiovascular risk. The WHI study demonstrated that certain HT regimens altered the levels of specific triacylglycerol species. When these same metabolites were analyzed for their association with incident CHD, a clear pattern emerged. The changes induced by the hormone therapy were directly correlated with future cardiovascular risk.

This provides powerful evidence that the metabolomic shift is not merely an incidental effect of the therapy; it is a key part of the causal pathway through which the therapy influences disease risk.

What Is the Role of Peptide Therapies?

This systems-level understanding extends to other advanced therapeutic protocols, such as Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy. Peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295 work by stimulating the body’s own production of growth hormone. This, in turn, influences a wide array of metabolic processes.

Growth hormone has significant effects on lipid and glucose metabolism, promoting lipolysis (fat breakdown) and influencing insulin sensitivity. Therefore, the therapeutic goal is to restore a more youthful metabolic profile. Monitoring downstream metabolites, such as specific lipid species and markers of insulin sensitivity, provides a quantitative measure of the therapy’s effectiveness.

It allows for a precise calibration of the protocol to achieve desired outcomes like improved body composition and metabolic efficiency, while ensuring the systemic changes are aligned with long-term health.

| Metabolite Family | Observed Change with HT | Associated Pathophysiological Mechanism | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acylcarnitines | Significant alterations in abundance, particularly with CEE-only therapy. | Indicates shifts in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and potential mitochondrial stress. | May serve as an early marker for therapy-induced metabolic inefficiency linked to cardiovascular strain. |

| Triacylglycerols | Discordant changes between CEE and CEE+MPA regimens. | Reflects altered lipid metabolism and transport; certain species are directly associated with CHD risk. | Provides a specific signature linking a therapy type to its cardiovascular risk profile. |

| Branched-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs) | Often elevated in states of insulin resistance. | Signal dysregulation in amino acid metabolism, upstream of glucose intolerance. | A key indicator of early metabolic syndrome, relevant for assessing baseline risk before starting any hormonal protocol. |

| Inflammatory Markers | Changes in metabolites linked to inflammatory pathways. | Reflects the pro- or anti-inflammatory effects of different hormonal inputs. | Connects hormonal status to systemic inflammation, a core driver of chronic disease. |

References

- Rupa Health. “Estrogen Metabolites in Urine ∞ Key Indicators of Hormone Metabolism.” Rupa Health, 10 Feb. 2025.

- Longevity Therapist. “Metabolic Health Risks.” Longevity Therapist, 2024.

- Loomba, Rohit, et al. “Metabolomic Effects of Hormone Therapy and Associations With Coronary Heart Disease Among Postmenopausal Women.” JAMA Cardiology, vol. 3, no. 1, 2018, pp. 54-61.

- Kubala, Jillian. “10 Natural Ways to Balance Your Hormones.” Healthline, 22 May 2023.

- Pilutin, Akingbolabo. “Hormonal Imbalance and Its Impact on Metabolic Disorders.” SciTechnol, 2023.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map, a detailed guide to the intricate biochemical landscape within you. It connects the symptoms you experience to the silent, molecular conversations that define your health. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active participation in your own well-being.

The numbers on a lab report and the names of specific metabolites are the vocabulary. The goal is to use this vocabulary to understand your own unique biological narrative.

Your Personal Health Blueprint

Consider the patterns discussed. Think about the persistent fatigue, the shifts in mood, or the changes in your body. See them now not as isolated frustrations, but as data points, signals from a system requesting attention and support. Your journey toward optimal health is yours alone.

The path is built upon this foundation of understanding, but it is ultimately paved with personalized choices and guided by a deep connection to your body’s feedback. What is your body telling you right now? How can this new understanding of your internal language help you ask better questions and seek more precise answers?