Fundamentals

Receiving a prostate-specific antigen, or PSA, test result can be a moment loaded with apprehension. That single number on a lab report often feels like a definitive judgment, a predictor of future health that is out of your control.

Your mind may immediately turn to worst-case scenarios, a natural response to a marker so closely associated with prostate cancer. The purpose of this discussion is to reframe that number. We will explore it as a piece of information, a biological signal that communicates much more about your body’s internal environment than you might realize. It is a data point reflecting the sensitive and dynamic nature of the prostate gland itself.

The prostate is a walnut-sized gland that is deeply integrated with your body’s urinary and reproductive systems. It produces a protein called prostate-specific antigen, whose primary function is to liquefy semen, aiding in fertility. A small amount of this protein naturally circulates in the bloodstream.

When the architecture of the prostate is disturbed, more PSA can enter the circulation, causing the number on your lab report to rise. This disturbance can come from many sources. Understanding these sources is the first step toward gaining agency over your health and interpreting your PSA level with clinical clarity.

The prostate gland functions as a sensitive barometer, with PSA levels reflecting systemic conditions well beyond the gland itself.

The Prostate Gland’s Immediate Environment

The prostate’s location, nestled deep within the pelvis, makes it susceptible to direct physical influence. Certain activities can cause a temporary and harmless increase in PSA levels by mechanically agitating the gland. This is a crucial concept, as it separates a transient fluctuation from a persistent, clinically significant trend. Recognizing these factors allows you to prepare for a PSA test in a way that yields the most accurate baseline reading possible.

One of the most common factors is recent ejaculation. Sexual activity within 48 hours of a blood draw can cause a temporary spike in PSA levels. The physiological processes involved in ejaculation cause contractions and activity within the gland, which can facilitate the release of more PSA into the bloodstream. This is a normal biological response. For this reason, physicians often recommend a brief period of abstinence before a scheduled PSA test to ensure the reading reflects the gland’s resting state.

Vigorous physical exercise, particularly activities that place pressure on the perineum, can have a similar effect. Cycling is a frequently cited example. The design of many bicycle seats places sustained pressure directly over the area of the prostate. This mechanical stress can lead to a temporary elevation in PSA.

This does not suggest that cycling is detrimental to prostate health; it simply means that the timing of such activities relative to testing is an important consideration. A long bike ride the day before a blood test might produce a result that is not truly representative of your baseline health.

Understanding Benign Influences

Other clinical and anatomical factors contribute to your baseline PSA level. As a man ages, the prostate gland tends to undergo a process of non-cancerous growth known as benign prostatic hyperplasia, or BPH. A larger prostate gland naturally produces more PSA.

Therefore, a gradual increase in PSA over the decades is an expected finding and is often correlated with age-related changes in prostate volume. A physician interprets a PSA result in the context of your age, establishing what is considered a normal range for your specific demographic.

Even a digital rectal exam (DRE), a standard component of a prostate health checkup, can cause a brief rise in PSA. The physical manipulation of the gland during the examination can release additional PSA into the bloodstream. This is why blood for a PSA test is typically drawn before a DRE is performed.

Similarly, more invasive procedures like a prostate biopsy will cause a significant, albeit temporary, increase in PSA levels that can take several weeks to return to baseline. These examples underscore the gland’s sensitivity to its immediate physical environment and the importance of context in the interpretation of any single PSA reading.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the immediate physical influences on the prostate, we can begin to appreciate the gland as a participant in the body’s broader systemic environment. The health of the prostate is deeply intertwined with your metabolic and inflammatory status.

Chronic, low-grade inflammation is a key physiological process that underpins many age-related conditions, and the prostate is not immune to its effects. Prostatitis, a term for inflammation of the prostate gland, is a common cause of elevated PSA levels and can arise from infections or other non-infectious inflammatory triggers. Lifestyle factors, particularly diet and body composition, are powerful modulators of this internal inflammatory state.

Your dietary patterns create the biochemical landscape of your body. The foods you consume are broken down into molecular components that can either promote or quell inflammatory pathways. A diet characterized by high amounts of processed foods, red meats, and certain fats can contribute to a pro-inflammatory state throughout the body, including within the delicate tissues of the prostate.

Conversely, a diet rich in plant-based foods provides a wealth of compounds that actively counter inflammation, supporting cellular health and stability. Viewing your nutritional choices through this lens transforms eating from a passive activity into a proactive strategy for managing your internal biology.

Dietary Patterns and Prostatic Inflammation

The connection between diet and inflammation is well-established. One of the core mechanisms involves the balance of fatty acids. The Western dietary pattern, for instance, is often high in omega-6 fatty acids found in many processed seed oils and animal products.

An excess of these can lead to the production of pro-inflammatory molecules like arachidonic acid. Research has shown that arachidonic acid can stimulate the growth of prostate cells in laboratory settings. In contrast, omega-3 fatty acids, found abundantly in cold-water fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts, are precursors to powerful anti-inflammatory compounds. Shifting the balance of these fats in your diet is a direct way to modulate your body’s inflammatory tone.

The table below outlines two contrasting dietary patterns and their typical effects on systemic inflammation, which in turn can influence the prostate microenvironment.

| Dietary Component | Pro-Inflammatory (Western Pattern) | Anti-Inflammatory (Mediterranean/Plant-Rich Pattern) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Fats |

High in saturated fats and omega-6 fatty acids (processed meats, many baked goods, certain vegetable oils). |

Rich in monounsaturated fats (olive oil) and omega-3 fatty acids (fatty fish, walnuts, flaxseed). |

| Protein Sources |

High consumption of red and processed meats. |

Emphasis on fish, legumes, and poultry, with lower red meat intake. |

| Carbohydrates |

Dominated by refined grains, sugars, and high-glycemic foods. |

Focus on whole grains, vegetables, and fruits, which are high in fiber. |

| Phytonutrients |

Low intake of vegetables and fruits, resulting in fewer protective compounds. |

High intake of vegetables, fruits, herbs, and spices, delivering a wide array of antioxidants and polyphenols. |

The Role of Specific Nutrients

Beyond broad dietary patterns, specific micronutrients and phytonutrients have been investigated for their direct impact on prostate health. These compounds often work by reducing oxidative stress, a close relative of inflammation, which can damage cells and contribute to PSA leakage.

- Lycopene ∞ This powerful antioxidant is a carotenoid pigment that gives tomatoes, watermelon, and pink grapefruit their characteristic red color. It has been studied for its ability to concentrate in prostate tissue and protect it from oxidative damage. Consuming cooked tomato products, like tomato sauce or paste, can increase the bioavailability of lycopene, making it easier for the body to absorb.

- Selenium and Zinc ∞ These are essential trace minerals that play a role in antioxidant defense systems within the body. Selenium is a component of enzymes that protect cells from oxidative damage. Zinc is found in high concentrations in healthy prostate tissue and is thought to play a role in maintaining normal cell function and inhibiting the production of dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a potent androgen that can drive prostate growth. Good sources of zinc include poultry, seafood, and pumpkin seeds.

- Phytoestrogens ∞ Found in soy products, flaxseeds, and other plants, these compounds have a mild estrogen-like effect. Isoflavones from soy, for example, have been associated with prostate health in some population studies. The mechanisms may involve modulating hormone signaling and reducing inflammation.

- Pomegranate ∞ This fruit is rich in unique antioxidants, such as punicalagins. Research has explored the potential for pomegranate extract to influence PSA levels, likely through its potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.

Dietary choices directly regulate the body’s inflammatory status, providing a powerful lever for influencing prostate health.

Metabolic Health and Its Prostatic Consequences

Your metabolic health, particularly your body composition and insulin sensitivity, is another critical factor. Obesity is now understood as a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation. Adipose tissue, or body fat, is not inert storage; it is an active endocrine organ that produces and secretes a variety of inflammatory signaling molecules called cytokines. These molecules circulate throughout the body and can contribute to inflammation within the prostate gland.

The relationship between obesity and PSA is complex. On one hand, obesity is associated with a higher risk of developing more aggressive forms of prostate cancer. On the other hand, several large studies have shown that men with a higher body mass index (BMI) often have lower PSA levels.

This seemingly paradoxical effect is thought to be due to hemodilution. Obese men tend to have a larger blood plasma volume, which can dilute the concentration of PSA, leading to a deceptively low reading. This makes it essential for clinicians to consider a man’s body composition when evaluating a PSA result.

A “normal” PSA in an obese man may warrant closer scrutiny than the same number in a lean man. Furthermore, conditions associated with obesity, such as high blood pressure and abnormal cholesterol levels, are also linked to changes in the prostate environment. Maintaining a healthy weight through a combination of diet and regular physical activity is therefore a cornerstone of managing both systemic inflammation and prostate health.

Academic

An academic exploration of lifestyle’s influence on PSA levels necessitates a shift in perspective, from viewing the prostate as an isolated organ to understanding it as a node within a complex network of interconnected biological systems.

The most illuminating path for this deep analysis is the examination of the interplay between metabolic syndrome, the endocrine function of adipose tissue, and the resulting inflammatory microenvironment of the prostate. This systems-biology approach reveals how disruptions in whole-body metabolism translate into specific molecular events within the prostate that can alter PSA expression and secretion, independent of underlying malignancy.

The Adipose Gland and Prostatic Inflammation

The modern understanding of adipose tissue has evolved. It is now recognized as a highly active endocrine and paracrine organ. Visceral adipose tissue, the fat surrounding the abdominal organs, is particularly metabolically active and pathogenic when in excess.

It secretes a host of signaling molecules known as adipokines, which include pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and leptin, as well as anti-inflammatory molecules like adiponectin. In a state of metabolic health, these signals are balanced. In the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome, this balance is disrupted, leading to a systemic, chronic, pro-inflammatory state.

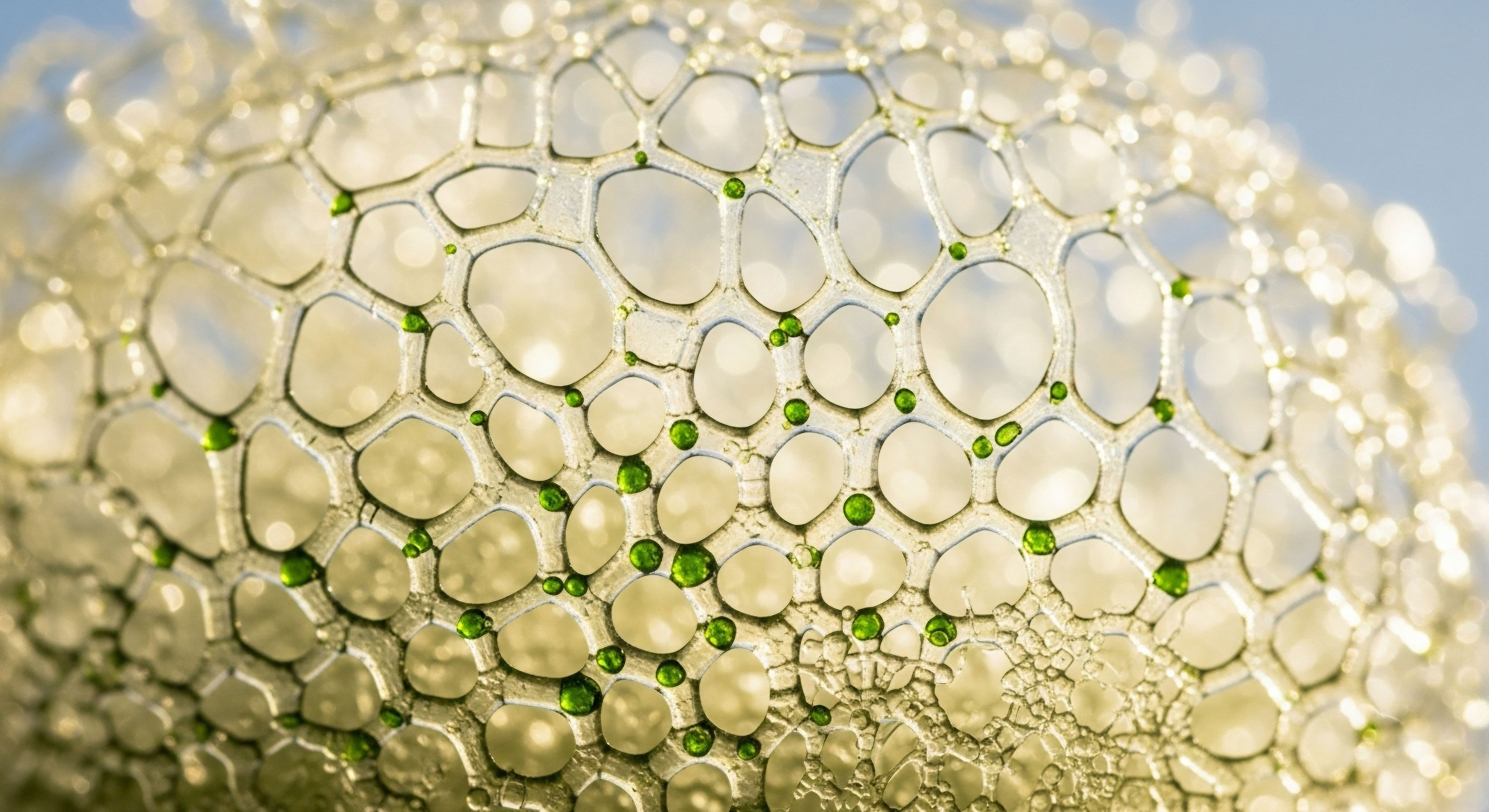

This systemic inflammation has direct consequences for the prostate. Circulating TNF-α and IL-6 can infiltrate the prostatic stroma and epithelium, promoting a local inflammatory response. This condition, often termed chronic subclinical prostatitis, can disrupt the integrity of the basal cell layer and the prostatic ductal architecture.

This structural disruption allows for increased leakage of PSA from the ductal lumen, where it is normally concentrated, into the surrounding capillaries and subsequently into the general circulation. The elevated PSA seen in this context is a direct biomarker of this localized, metabolically-driven inflammation.

What Is the Role of Insulin Resistance?

A central feature of metabolic syndrome is insulin resistance. In this state, cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin, prompting the pancreas to produce ever-higher amounts in a condition known as hyperinsulinemia. Insulin, along with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), is a potent mitogen, a substance that encourages cell division and proliferation.

The prostate gland is highly responsive to these growth signals. Elevated levels of insulin and IGF-1 can stimulate the proliferation of both benign and malignant prostate epithelial cells. This increased cellular turnover and glandular volume can contribute to higher overall PSA production. Therefore, the hyperinsulinemia that characterizes metabolic syndrome can directly influence PSA levels by promoting glandular growth, creating a feedback loop where poor metabolic health drives prostatic changes.

Metabolic syndrome transforms adipose tissue into an inflammatory organ, directly altering the prostate’s cellular environment and influencing PSA levels.

The table below details the specific molecular mechanisms through which components of metabolic syndrome can influence the prostate and PSA levels.

| Component of Metabolic Syndrome | Key Molecular Mediator | Mechanism of Action on the Prostate |

|---|---|---|

| Visceral Obesity |

Leptin, TNF-α, IL-6 |

Promotes a pro-inflammatory state within the prostate stroma, increases oxidative stress, and disrupts epithelial barrier integrity, leading to increased PSA leakage. |

| Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia |

Insulin, Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) |

Acts as a mitogen, stimulating the proliferation of prostate epithelial cells. This increases overall glandular volume and PSA production capacity. |

| Dyslipidemia |

High Triglycerides, Low HDL Cholesterol |

Associated with increased intraprostatic inflammation and oxidative stress. Cholesterol is also a precursor for androgen synthesis, which can influence prostate cell activity. |

| Hypertension |

Angiotensin II, Endothelial Dysfunction |

Contributes to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress. Reduced blood flow and hypoxia can further exacerbate inflammatory conditions within the prostate. |

How Do Lifestyle Interventions Disrupt These Pathways?

Understanding these mechanisms illuminates why specific lifestyle interventions are effective. These are not abstract wellness recommendations; they are targeted strategies to reverse the underlying pathophysiology.

- Dietary Modification ∞ A diet low in refined carbohydrates and high in fiber, healthy fats, and phytonutrients directly combats insulin resistance and reduces the inflammatory load. By improving insulin sensitivity, the body’s need to produce excess insulin is diminished, reducing the mitogenic stimulation of the prostate. Phytonutrients from vegetables, fruits, and spices actively inhibit inflammatory pathways, such as the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway, which is a master regulator of the inflammatory response.

- Consistent Physical Activity ∞ Exercise has profound effects on metabolic health. It improves insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle, reducing the burden on the pancreas. It also promotes the reduction of visceral adipose tissue, thereby decreasing the secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines. Furthermore, exercise can stimulate the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines, actively countering the systemic inflammation driven by obesity.

- Stress Modulation ∞ Chronic psychological stress, acting through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, results in elevated cortisol levels. While acutely anti-inflammatory, chronic elevation of cortisol can dysregulate the immune system and contribute to insulin resistance, further linking the body’s stress response system to the metabolic drivers of prostatic inflammation. Practices like mindfulness and adequate sleep help regulate the HPA axis, mitigating this effect.

In conclusion, a sophisticated understanding of PSA dynamics requires looking beyond the prostate itself. The gland is a sensitive endpoint that reflects the body’s overall metabolic and inflammatory state. Lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, and stress management are not merely “healthy habits”; they are powerful biochemical interventions that can modulate the very pathways that lead to prostatic inflammation and altered PSA levels.

Interpreting a PSA result, therefore, necessitates a holistic assessment of the individual’s metabolic health, as the number on the page is often a commentary on the health of the entire system.

References

- Paller, C. J. et al. “A randomized phase II study of pomegranate extract for men with rising PSA following initial therapy for localized prostate cancer.” Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, vol. 16, no. 1, 2013, pp. 50-55.

- Hamilton, R. J. et al. “The influence of lifestyle changes (diet, exercise and stress reduction) on prostate cancer tumour biology and patient outcomes ∞ A systematic review.” BJU International, vol. 131, no. 5, 2023, pp. 552-569.

- Lin, P.-H. et al. “Lifestyle and risk factors associated with elevated prostate-specific antigen levels in rural men ∞ implications for health counseling.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 20, no. 4, 2023, p. 3479.

- Tewari, R. et al. “Dietary Factors and Supplements Influencing Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Concentrations in Men with Prostate Cancer and Increased Cancer Risk ∞ An Evidence Analysis Review Based on Randomized Controlled Trials.” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 19, 2022, p. 4078.

- Godos, J. et al. “Dietary Factors and Prostate Cancer Development, Progression, and Reduction.” Cancers, vol. 14, no. 15, 2022, p. 3721.

- Algotar, Ashish M. et al. “Chronic use of NSAIDs and/or statins does not affect PSA or PSA velocity in men at high risk for prostate cancer.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, vol. 23, no. 10, 2014, pp. 2196-2198.

- Vidal, A. C. et al. “Aspirin, NSAIDs, and risk of prostate cancer ∞ results from the REDUCE study.” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 21, no. 4, 2015, pp. 756-762.

- Chang, S. L. et al. “Statin use and risk of prostate cancer ∞ a meta-analysis of observational studies.” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 10, 2012, e46691.

- He, K. et al. “Clinical factors affecting prostate-specific antigen levels in prostate cancer patients undergoing radical prostatectomy ∞ a retrospective study.” Future Science OA, vol. 7, no. 3, 2021, FSO675.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological terrain influencing your prostate health. It connects the dots between your daily choices and the subtle signals your body produces, like the PSA level. This knowledge is designed to shift your perspective from one of passive concern to one of active participation.

The number on your lab report is a single data point in a continuous conversation you are having with your body. Your lifestyle choices are your side of that dialogue.

Consider the systems at play within you. Think of the intricate network connecting your metabolism, your inflammatory status, and the health of every cell, including those in your prostate. How might your daily routines be shaping this internal environment? This journey of understanding is a deeply personal one.

The path toward sustained wellness is built upon a foundation of this knowledge, tailored to your unique biology and life circumstances. The ultimate goal is to cultivate an internal state that promotes resilience and vitality, allowing you to function with clarity and confidence for years to come.