Fundamentals

Have you ever experienced those subtle shifts within your body, a feeling of being slightly out of sync, perhaps a persistent fatigue or an unexpected change in your monthly rhythm? These sensations, often dismissed as simply “getting older” or “stress,” frequently point to a deeper conversation happening within your biological systems.

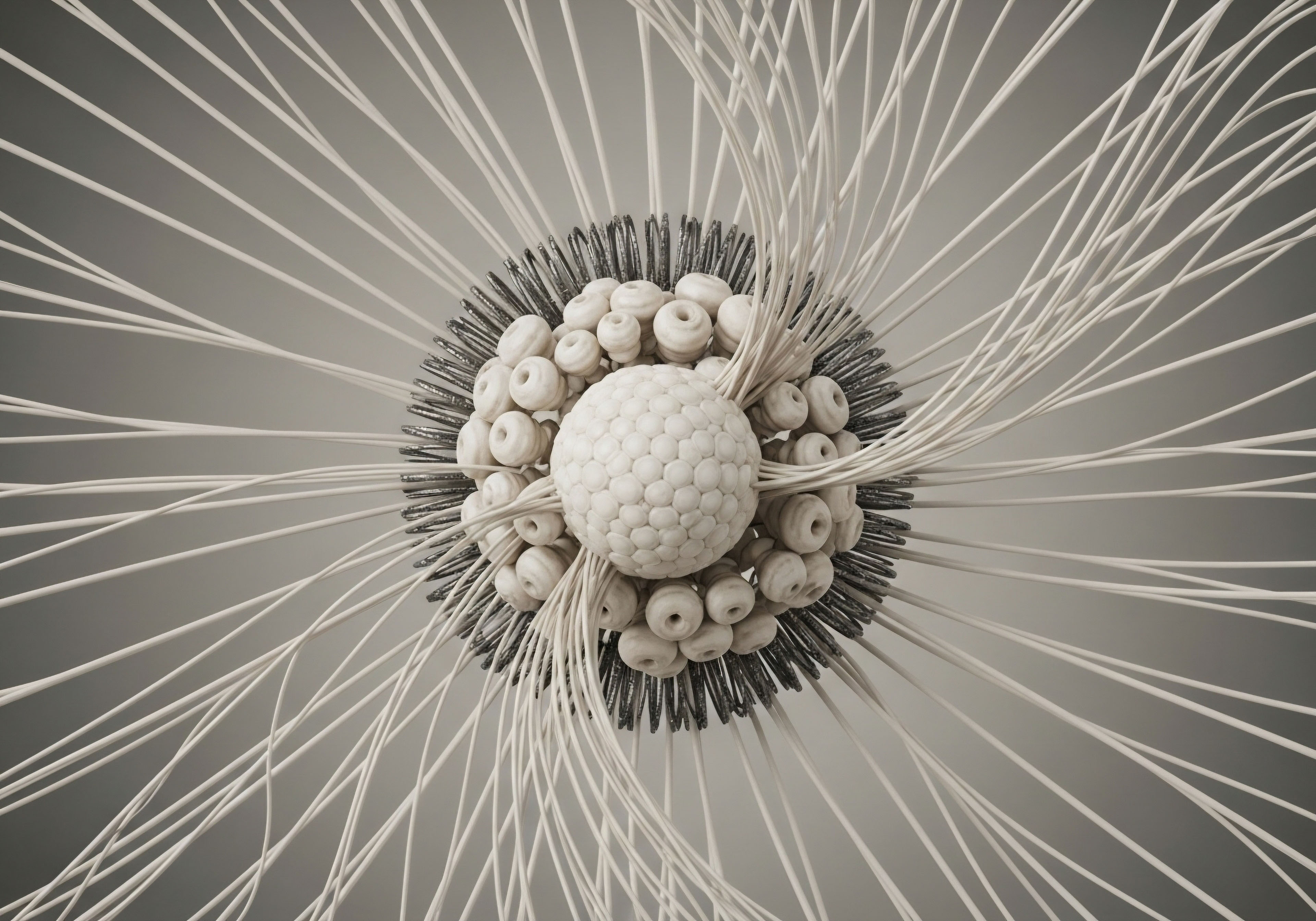

Your body communicates through an intricate network of chemical messengers, the endocrine system, which orchestrates nearly every aspect of your vitality and function. When this delicate balance is disturbed, even by seemingly innocuous habits, the reverberations can be felt throughout your entire being.

Understanding your own physiology is the first step toward reclaiming optimal health. Hormones, these powerful signaling molecules, regulate everything from your mood and energy levels to your reproductive capacity and metabolic rate. They are produced by various glands and travel through your bloodstream, delivering precise instructions to cells and tissues. A disruption in this sophisticated internal messaging service can lead to a cascade of symptoms that leave you feeling disconnected from your true potential.

For women, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, often referred to as the HPG axis, stands as a central pillar of hormonal health. This axis represents a complex feedback loop involving the hypothalamus in the brain, the pituitary gland at the base of the brain, and the ovaries.

The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which prompts the pituitary to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins then signal the ovaries to produce sex steroids, primarily estrogen and progesterone, which govern the menstrual cycle, fertility, and numerous other physiological processes.

The body’s endocrine system acts as a sophisticated internal communication network, with hormones serving as vital messengers that orchestrate physiological balance.

When alcohol enters the system, it does not simply affect one organ; it acts as a systemic disruptor, influencing multiple biological pathways simultaneously. The liver, being the primary site of alcohol metabolism, bears a significant burden. This organ is not only responsible for detoxifying alcohol but also plays a central role in the metabolism and clearance of hormones. Any impairment to liver function can therefore have far-reaching consequences for hormonal equilibrium.

Consider the profound impact on the HPG axis. Research indicates that alcohol consumption can interfere with the pulsatile release of GnRH from the hypothalamus. This interference can lead to a subsequent decrease in the pituitary’s secretion of LH and FSH, thereby diminishing the ovarian signals necessary for healthy follicular development and ovulation. Such a disruption can manifest as irregular menstrual cycles, anovulation, or even contribute to earlier onset of menopausal symptoms.

The effects extend beyond reproductive function, touching upon growth and bone health, particularly when alcohol consumption occurs during critical developmental periods like puberty. Alterations in hormonal levels in postmenopausal women also signify alcohol’s broad influence across different life stages. Understanding these foundational concepts provides a lens through which to view the more intricate mechanisms of alcohol’s hormonal impact.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding, we can now examine the specific clinical pathways through which alcohol exerts its influence on female hormonal health. The body’s endocrine symphony relies on precise timing and balanced levels of various hormones. Alcohol, a potent xenobiotic, can throw this delicate orchestration into disarray, affecting not only the reproductive hormones but also those governing stress response and metabolic function.

How Does Alcohol Alter Estrogen Metabolism?

One of the most well-documented effects of alcohol in women involves the metabolism of estrogen. The liver is central to estrogen detoxification and elimination. Alcohol metabolism in the liver utilizes specific enzyme systems, particularly the cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP450). When the liver is processing alcohol, its capacity to metabolize estrogens can be compromised. This can lead to altered ratios of estrogen metabolites or even an accumulation of certain estrogen forms.

Studies reveal that alcohol consumption can increase circulating estradiol levels, particularly in premenopausal women and those undergoing hormonal optimization protocols. This elevation can occur through several mechanisms. Alcohol may promote the activity of aromatase, an enzyme found in various tissues, including adipose tissue, which converts androgens (like testosterone) into estrogens.

An increased conversion rate means more estrogen is produced from existing androgen precursors. Additionally, alcohol can impede the clearance of estrogens from the bloodstream, prolonging their presence and activity within the body.

Alcohol disrupts the liver’s capacity to metabolize estrogens, potentially increasing circulating estradiol levels and altering beneficial metabolite ratios.

For women considering or undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), understanding this interaction is paramount. While TRT for women typically involves low-dose testosterone cypionate via subcutaneous injection, the body naturally converts some testosterone to estrogen via aromatase. If alcohol enhances this conversion or impairs estrogen clearance, it could lead to higher estrogen levels than desired, potentially negating some benefits of TRT or contributing to symptoms associated with estrogen dominance.

What Is Alcohol’s Impact on Progesterone Balance?

Progesterone, often called the “calming hormone,” plays a vital role in regulating the menstrual cycle, supporting pregnancy, and balancing estrogen’s effects. Research indicates that moderate alcohol consumption can lead to decreased progesterone levels in premenopausal women. This reduction can contribute to symptoms such as irregular cycles, heightened premenstrual symptoms, or even luteal phase defects, where the second half of the menstrual cycle is shortened or less robust.

The mechanisms behind this progesterone reduction are complex but may involve alcohol’s influence on ovarian function or the adrenal glands, which also produce progesterone. For women experiencing symptoms of progesterone insufficiency, such as mood changes, sleep disturbances, or heavy bleeding, alcohol consumption could exacerbate these challenges. Targeted progesterone therapy, often prescribed based on menopausal status, aims to restore this balance, but its efficacy could be undermined by ongoing alcohol intake.

How Does Alcohol Affect the Adrenal and Thyroid Axes?

The body’s stress response system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, is also significantly affected by alcohol. Alcohol acts as a physiological stressor, triggering the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus, which then stimulates the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This ultimately leads to increased production and secretion of cortisol from the adrenal glands.

Chronic alcohol exposure can lead to a dysregulated HPA axis, characterized by elevated baseline cortisol levels and an altered diurnal rhythm. Sustained high cortisol can suppress other hormonal pathways, including the HPG axis, and contribute to symptoms like fatigue, weight gain, sleep disturbances, and mood dysregulation. This chronic stress response can also impact the effectiveness of protocols designed to support adrenal health or manage stress-related hormonal imbalances.

The thyroid gland, a master regulator of metabolism, is not immune to alcohol’s effects. While some studies suggest a potential reduction in thyroid cancer risk with alcohol, other research indicates an increased risk of thyroid enlargement, particularly in women. Alcohol can directly suppress thyroid function through cellular toxicity and indirectly by blunting the response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH).

This can lead to decreased levels of peripheral thyroid hormones, triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), during chronic use and withdrawal, impacting metabolic rate, energy, and cognitive function.

Consider the following table summarizing alcohol’s impact on key female hormones ∞

| Hormone System | Alcohol’s Primary Effect | Potential Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| HPG Axis (Estrogen) | Increased circulating estradiol, altered metabolism, enhanced aromatase activity. | Irregular cycles, estrogen dominance symptoms, increased breast tissue sensitivity. |

| HPG Axis (Progesterone) | Decreased progesterone levels. | Luteal phase defects, heightened premenstrual symptoms, mood changes. |

| HPA Axis (Cortisol) | Increased cortisol secretion, HPA axis dysregulation. | Chronic stress response, fatigue, sleep disturbances, metabolic shifts. |

| Thyroid Hormones | Suppressed peripheral thyroid hormones, altered TRH response, thyroid enlargement risk. | Lower metabolic rate, energy deficits, cognitive slowing. |

Does Alcohol Influence Metabolic Hormones?

Alcohol also interacts with metabolic hormones, particularly those involved in glucose regulation. Some studies suggest that moderate alcohol consumption might improve insulin sensitivity and reduce fasting insulin and HbA1c concentrations in non-diabetic women. This effect, however, is not universally consistent across all research and appears to be more pronounced in women than in men.

While this might seem like a beneficial effect, it is important to consider the broader context. Alcohol provides empty calories and can disrupt gut health, which indirectly influences metabolic function and hormonal balance. The overall impact on metabolic health is complex and depends on the quantity and frequency of consumption, as well as individual metabolic resilience.

For individuals seeking comprehensive metabolic recalibration, including those on Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy (e.g. Sermorelin, Ipamorelin / CJC-1295 for anti-aging, muscle gain, fat loss, and sleep improvement), alcohol’s metabolic effects warrant careful consideration. Alcohol can interfere with sleep architecture, which is critical for natural growth hormone release, potentially undermining the benefits of such peptide protocols.

Understanding these intermediate pathways provides a clearer picture of how alcohol can subtly, yet significantly, undermine hormonal equilibrium, making personalized wellness protocols even more essential for restoring balance.

Academic

To truly grasp the profound influence of alcohol on female physiology, we must delve into the molecular and cellular mechanisms that underpin its systemic disruption. The intricate dance of hormones, enzymes, and receptors is susceptible to interference, and alcohol, or ethanol, acts as a pervasive agent capable of altering this delicate choreography at multiple levels.

Our focus here centers on the deep endocrinology of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and the sophisticated processes of hepatic hormone metabolism, which together represent critical vulnerabilities to alcohol exposure.

Molecular Disruption of the HPG Axis

The HPG axis is a finely tuned neuroendocrine feedback loop, commencing with the pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from specialized neurons in the hypothalamus. This pulsatility is paramount for stimulating the anterior pituitary to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins then act on the ovaries, driving follicular development, ovulation, and the synthesis of sex steroids, primarily estradiol and progesterone.

Alcohol exerts its disruptive force primarily at the hypothalamic level, interfering with the rhythmic secretion of GnRH. Studies in animal models have demonstrated that alcohol can reduce GnRH release from hypothalamic slices, leading to decreased LH levels in the bloodstream. This suppression of GnRH pulsatility directly impairs the downstream signaling to the pituitary and ovaries.

The precise molecular targets for alcohol’s action on GnRH neurons are still under investigation, but they likely involve alterations in neurotransmitter systems that regulate GnRH, such as endogenous opioid peptides like beta-endorphin, which normally restrain GnRH secretion. Alcohol’s interaction with these inhibitory pathways can further compound the dysregulation.

Beyond the hypothalamus, alcohol may also directly affect pituitary responsiveness to GnRH, though the hypothalamic effect appears to be the primary driver of gonadotropin suppression. At the ovarian level, alcohol can directly impair follicular development and steroidogenesis. It can disrupt the intricate signaling pathways within granulosa cells, which are responsible for producing estrogen and progesterone under the influence of LH and FSH.

This direct ovarian toxicity, combined with central HPG axis suppression, culminates in impaired ovulation and altered sex steroid production, leading to menstrual irregularities, anovulation, and subfertility.

Alcohol primarily disrupts the HPG axis by impairing hypothalamic GnRH pulsatility, leading to reduced LH and FSH secretion and direct ovarian dysfunction.

Complexities of Hepatic Hormone Metabolism

The liver serves as the central hub for the metabolism and clearance of steroid hormones. Alcohol consumption profoundly impacts these hepatic processes, leading to altered circulating hormone levels and metabolite profiles. The primary enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism, alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), compete for metabolic resources with the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system, which is crucial for steroid hormone biotransformation.

Specifically, alcohol can influence the activity of various CYP isoforms, such as CYP1A1, CYP1B1, and CYP3A4, which are involved in estrogen hydroxylation. Estrogens are metabolized into various forms, including 2-hydroxyestrogens (2-OHE), 4-hydroxyestrogens (4-OHE), and 16-hydroxyestrogens (16-OHE). The balance between these metabolites is clinically significant, as 2-OHE metabolites are generally considered more protective, while 4-OHE and 16-OHE metabolites are associated with increased proliferative activity and potential genotoxicity.

Alcohol consumption can shift estrogen metabolism towards less favorable pathways, potentially increasing the production of the more genotoxic 4-OHE and 16-OHE metabolites, while decreasing the protective 2-OHE forms. This alteration in estrogen metabolite ratios, coupled with impaired conjugation pathways like glucuronidation and sulfation (which prepare hormones for excretion), can lead to higher levels of circulating, biologically active estrogens.

This mechanism contributes to the observed increase in estradiol levels in women who consume alcohol, particularly postmenopausal women where peripheral aromatization in adipose tissue becomes a more significant source of estrogen.

The enterohepatic circulation of estrogens also plays a role. Estrogens conjugated in the liver are excreted into the bile, deconjugated by gut bacteria, and reabsorbed. Alcohol can disrupt the gut microbiome, altering this enterohepatic recirculation and potentially leading to increased reabsorption of unconjugated estrogens, further contributing to elevated systemic levels.

Adrenal Steroidogenesis and Stress Response Dysregulation

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, responsible for the body’s stress response, is highly sensitive to alcohol. Acute alcohol intake triggers a robust activation of the HPA axis, leading to increased secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus, followed by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary, and ultimately, cortisol from the adrenal cortex.

Chronic alcohol exposure leads to persistent HPA axis activation and dysregulation. This can manifest as elevated basal cortisol levels, a blunted diurnal cortisol rhythm, and impaired negative feedback mechanisms. The sustained hypercortisolemia can have widespread effects on other endocrine systems, including suppression of the HPG axis, insulin resistance, and alterations in thyroid hormone sensitivity.

The adrenal glands also produce dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfated form, DHEA-S, which are precursors to sex hormones. Chronic alcohol use can alter the balance of these adrenal androgens, further contributing to hormonal imbalances.

Consider the intricate interplay of these pathways in the context of personalized wellness protocols. For women experiencing symptoms related to hormonal changes, such as those in perimenopause or postmenopause, understanding alcohol’s impact on estrogen and progesterone metabolism is vital. Protocols involving low-dose testosterone or progesterone therapy aim to restore specific hormonal levels. If alcohol is simultaneously increasing estrogen and decreasing progesterone, it creates a counterproductive environment, making it harder to achieve optimal balance.

Furthermore, the HPA axis dysregulation induced by alcohol can undermine the effectiveness of interventions aimed at stress management or adrenal support. The body’s ability to respond appropriately to stressors is compromised, making individuals more vulnerable to the physiological and psychological consequences of chronic stress.

The table below illustrates the specific enzymatic and metabolic pathways affected by alcohol ∞

| Hormone/Pathway | Enzymes/Mechanisms Affected by Alcohol | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Metabolism | CYP450 isoforms (CYP1A1, CYP1B1, CYP3A4), Aromatase activity, Glucuronidation, Sulfation. | Shift to less favorable estrogen metabolites (e.g. higher 16-OHE), impaired clearance, elevated circulating estradiol. |

| HPG Axis Regulation | Hypothalamic GnRH pulsatility, Pituitary LH/FSH secretion, Ovarian steroidogenesis. | Suppressed ovarian function, irregular cycles, anovulation. |

| Adrenal Steroidogenesis | CRH, ACTH, Cortisol synthesis and rhythm, DHEA/DHEA-S balance. | Chronic hypercortisolemia, impaired stress response, altered adrenal androgen production. |

| Thyroid Hormone Conversion | TRH response, Peripheral T4 to T3 conversion, Direct cellular toxicity. | Reduced active thyroid hormone levels, blunted metabolic rate. |

The implications for personalized wellness protocols are significant. For instance, in men undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), alcohol’s ability to increase aromatase activity could lead to higher estrogen conversion, necessitating careful monitoring and potentially the use of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole. Similarly, for women, the interplay between alcohol and endogenous estrogen levels becomes a critical consideration in managing symptoms related to hormonal balance.

Even therapies like Pentadeca Arginate (PDA), used for tissue repair and inflammation, could be indirectly impacted. Chronic alcohol consumption often leads to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, creating a physiological environment that requires more intensive repair and anti-inflammatory support. Understanding these deep biological interactions allows for a more precise and effective approach to biochemical recalibration, ensuring that interventions are not undermined by lifestyle factors.

References

- Emanuele, Mary Ann, Frederick Wezeman, and Nicholas V. Emanuele. “Alcohol’s Effects on Female Reproductive Function.” Alcohol Research & Health, vol. 33, no. 1-2, 2010, pp. 108-121.

- Sarkola, Taisto, Heikki Mäkisalo, Tatsushige Fukunaga, and C. J. Peter Eriksson. “Acute effect of alcohol on estradiol, estrone, progesterone, prolactin, cortisol, and luteinizing hormone in premenopausal women.” Alcoholism ∞ Clinical and Experimental Research, vol. 23, no. 6, 1999, pp. 976-982.

- Holzhauer, Cathryn, et al. “Fluctuations in progesterone moderate the relationship between daily mood and alcohol use in young adult women.” Addictive Behaviors, vol. 100, 2020, p. 106146.

- Tin, Sandar, et al. “Alcohol intake and endogenous sex hormones in women ∞ Meta-analysis of cohort studies and Mendelian randomization.” Cancer, vol. 130, no. 13, 2024, pp. 2005-2016.

- Emanuele, Mary Ann, and Nicholas V. Emanuele. “Alcohol and the Endocrine System.” Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 95, no. 2, 2011, pp. 339-355.

- Badrick, E. et al. “The relationship between alcohol consumption and cortisol secretion in an aging cohort.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 93, no. 1, 2008, pp. 74-79.

- Valeix, Pierre, et al. “Effects of light to moderate alcohol consumption on thyroid volume and thyroid function.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 68, no. 6, 2008, pp. 988-995.

- Bielinski, Stephen J. et al. “Alcohol Consumption and Urinary Estrogens and Estrogen Metabolites in Premenopausal Women.” Cancer Causes & Control, vol. 27, no. 2, 2016, pp. 221-230.

- Sarkola, Taisto, and C. J. Peter Eriksson. “Effects of alcohol on the female endocrine system.” Alcoholism ∞ Clinical and Experimental Research, vol. 26, no. 11, 2002, pp. 1618-1622.

- Polk, David M. et al. “Moderate alcohol consumption increases insulin sensitivity and ADIPOQ expression in postmenopausal women ∞ a randomised, crossover trial.” Diabetologia, vol. 51, no. 8, 2008, pp. 1375-1381.

Reflection

As you consider the intricate details of how alcohol interacts with your hormonal pathways, reflect on your own unique biological blueprint. The knowledge presented here is not merely a collection of facts; it serves as a mirror, allowing you to observe the subtle and profound ways your lifestyle choices can influence your internal equilibrium. Your body possesses an innate intelligence, constantly striving for balance, and understanding its language empowers you to support that inherent capacity.

This exploration into alcohol’s endocrine effects is a starting point, an invitation to a deeper conversation with your own physiology. Each individual’s response to external factors is unique, shaped by genetic predispositions, environmental exposures, and the complex interplay of their entire system. Armed with this understanding, you are better equipped to make informed decisions that align with your personal health goals.

Consider this journey of self-discovery a continuous process. Reclaiming vitality and function without compromise requires a commitment to listening to your body’s signals, interpreting them through a scientific lens, and then applying personalized strategies. This path involves thoughtful consideration of your habits and a willingness to recalibrate when necessary, always with the aim of optimizing your well-being.