Fundamentals

You may be experiencing a profound sense of fatigue, a persistent brain fog, or an inability to manage your weight, even when your thyroid lab results return within the “normal” range. This experience is deeply personal and can be incredibly frustrating, leaving you feeling unheard by the very system you turned to for answers.

Your feelings are valid; they are signals from your body communicating a deeper story about its internal environment. The narrative of your health is written not just in the blood that is drawn, but in the complex, living ecosystem within your digestive tract. Understanding this connection is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

The journey of a thyroid hormone from production to cellular action is a sophisticated process. Your thyroid gland primarily produces a prohormone called thyroxine, or T4. Think of T4 as a carefully packaged shipment of raw materials. For this material to be useful, it must be unpackaged and converted into its biologically active form, triiodothyronine, or T3.

It is T3 that docks with receptors on your cells and directs metabolic processes, influencing everything from your heart rate and body temperature to your energy levels and cognitive clarity. While a significant portion of this conversion happens in the liver, a critical and often underestimated part of this biochemical activation takes place within your gut.

Your gut microbiome functions as a vital endocrine organ, performing the final, critical steps to activate a portion of your body’s thyroid hormone supply.

The Unseen Workforce in Your Gut

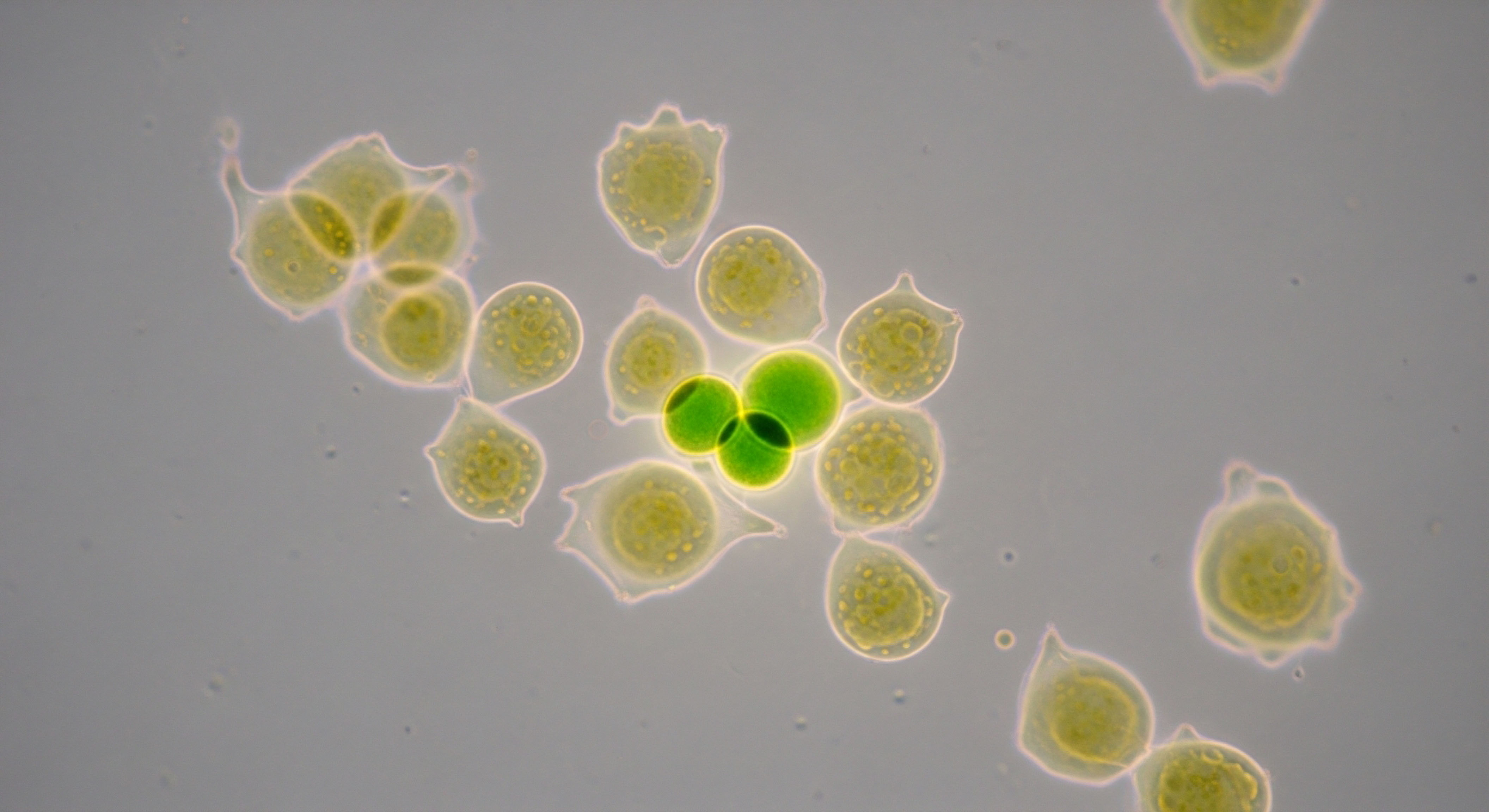

Residing within your gastrointestinal tract are trillions of microorganisms, a dynamic community collectively known as the gut microbiome. This internal ecosystem is a bustling metropolis of chemical activity. For years, its role was understood primarily in the context of digestion and nutrient absorption.

We now recognize its profound influence extends to regulating immunity, neurotransmitter production, and, crucially, endocrine function. Approximately 20% of your body’s T4 is converted into active T3 through the direct action of your gut bacteria. This means that the health and composition of your microbiome can directly impact the amount of usable thyroid hormone available to your cells.

When this microbial community is in balance, it works in silent partnership with your body’s systems. Specific beneficial bacteria produce enzymes that are essential for this hormonal conversion process. They are, in effect, the skilled technicians who perform the final assembly on the T4 prohormone, turning it into the T3 that your body can actually use.

A disruption in this workforce, a state known as dysbiosis, can therefore create a systemic bottleneck. The raw materials (T4) may be plentiful, yet the final, active product (T3) becomes scarce, leading to the familiar symptoms of an underactive thyroid.

Why Your Lab Results Tell Only Part of the Story

Standard thyroid panels typically measure Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) and free T4. These markers indicate that the initial signaling from your brain to your thyroid is working and that the gland is producing its primary hormone. They do not, however, always provide a clear picture of the conversion process occurring in peripheral tissues like the liver and the gut.

It is entirely possible to have “perfect” TSH and T4 levels while simultaneously suffering from a low level of active T3 due to poor conversion. This is where the lived experience of your symptoms provides essential data that laboratory tests might miss.

This condition, where symptoms of hypothyroidism persist despite normal lab values, is sometimes referred to as euthyroid sick syndrome. It highlights a system-wide dysfunction, and the gut is a primary location to investigate.

The health of your intestinal lining, the balance of your microbial populations, and your body’s ability to absorb key nutrients all converge to influence this final, critical step in thyroid hormone activation. Your journey toward wellness, therefore, involves looking beyond the thyroid gland itself and turning your attention to the foundational health of your digestive system, the site of this essential biochemical transformation.

Intermediate

Understanding that the gut is a site of thyroid hormone activation opens a new dimension in managing metabolic health. This knowledge shifts the focus toward the specific biological mechanisms at play within the intestinal environment.

The conversion of T4 to T3 in the gut is not a single event but a series of sophisticated biochemical processes, each facilitated by the microbial inhabitants of your digestive tract and the nutrients they help you absorb. By examining these pathways, we can appreciate how a balanced microbiome acts as a precise regulator of endocrine function.

The Chemical Mechanisms of Conversion

Your gut bacteria employ several distinct strategies to influence the pool of active T3 hormone. These mechanisms work in concert, demonstrating the deep integration of your microbiome with your body’s endocrine signaling. A healthy gut environment ensures these pathways function optimally, providing a steady supply of active thyroid hormone to your cells.

The Sulfatase Pathway

One of the primary routes for T3 activation in the gut involves a process of sulfation and desulfation. In the liver, T4 can be converted into an inert, sulfated form called T3 Sulfate (T3S). This molecule is then excreted via bile into the intestines.

Here, beneficial gut bacteria produce a crucial enzyme known as intestinal sulfatase. This enzyme cleaves the sulfate group from the T3S molecule, liberating it and converting it back into active, usable T3. This T3 can then be reabsorbed into the bloodstream and utilized by the body. A gut microbiome lacking in these sulfatase-producing bacteria will be inefficient at this process, leading to a net loss of potential thyroid hormone.

Direct Deiodinase Activity

The enzymes responsible for converting T4 to T3 throughout the body are called deiodinases. They work by removing one iodine atom from the T4 molecule. While the primary deiodinase enzymes are found in tissues like the liver and muscle, emerging research indicates that certain species of gut bacteria possess their own deiodinase-like enzymatic machinery.

These bacteria can perform the conversion directly within the gut, contributing to the overall pool of circulating T3. The composition of the microbiome, therefore, determines the level of this direct enzymatic support for thyroid function.

The Role of Bile Acids

The connection extends even to the metabolism of fats. Your liver produces primary bile acids to help with digestion, and these are secreted into the gut. Your gut bacteria then metabolize these primary bile acids, transforming them into secondary bile acids.

These secondary bile acids have been shown to increase the activity of the body’s main deiodinase enzymes, particularly the ones located in the liver and other tissues. A healthy microbial ecosystem that efficiently produces secondary bile acids can therefore amplify the T4-to-T3 conversion process system-wide, creating a positive feedback loop that supports overall metabolic health.

A diverse and healthy gut microbiome directly manufactures enzymes and metabolites that are essential for activating thyroid hormone.

Which Nutrients Are Most Critical for T3 Activation?

The enzymatic processes of thyroid hormone synthesis and conversion are heavily dependent on specific micronutrients. The health of your gut lining and the balance of your microbiome directly dictate how efficiently you absorb these vital cofactors from your diet and supplements. Gut dysbiosis can lead to inflammation and damage to the intestinal wall, impairing nutrient absorption and creating deficiencies that compromise thyroid function, even with adequate intake.

- Selenium ∞ This mineral is a critical component of the deiodinase enzymes. Without sufficient selenium, the conversion of T4 to T3 is significantly hindered. The gut microbiome influences selenium availability in the body.

- Zinc ∞ Zinc is required for the synthesis of both Thyroid-Releasing Hormone (TRH) from the hypothalamus and Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) from the pituitary. It also plays a role in helping T3 bind to its cellular receptors.

- Iron ∞ Healthy iron levels are necessary for the proper functioning of the thyroid peroxidase (TPO) enzyme, which is essential for producing thyroid hormones in the first place. Anemia is commonly linked with hypothyroidism.

Key Bacterial Players and Their Roles

While the research is still evolving, specific genera of bacteria have been identified as having particularly important roles in the thyroid-gut axis. The balance between beneficial and potentially harmful bacteria can significantly sway thyroid hormone availability.

| Bacterial Genus | Primary Role in Thyroid Axis | Associated Health State |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus | Supports a healthy gut barrier, modulates immune function, and may improve absorption of key minerals like selenium and zinc. Certain species have shown potential to support thyroid function. | Generally associated with a healthy, balanced microbiome. Often found in probiotic supplements. |

| Bifidobacterium | Similar to Lactobacillus, this genus helps maintain intestinal integrity, reduces inflammation, and supports a healthy immune response, which is crucial in preventing autoimmune thyroid conditions. | A hallmark of a healthy gut ecosystem. Its presence is linked to reduced inflammation. |

| Enterococcus | While some species are commensal, an overgrowth of certain Enterococcus strains has been observed in some cases of hyperthyroidism, suggesting a potential link to gut imbalance in thyroid disease. | Overgrowth can be indicative of dysbiosis and may contribute to an inflammatory gut environment. |

| Gram-negative Bacteria (LPS-producing) | These bacteria contain Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in their cell walls. When the gut barrier is compromised, LPS can enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation and directly inhibiting T4-to-T3 conversion enzymes. | Associated with “leaky gut,” systemic inflammation, and suppression of active thyroid hormone. |

Maintaining a gut environment that favors the proliferation of beneficial genera like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium while keeping potentially inflammatory bacteria in check is a foundational strategy for supporting robust thyroid hormone conversion and overall metabolic wellness.

Academic

The intricate relationship between the gut microbiome and thyroid homeostasis represents a frontier in endocrinology and systems biology. Moving beyond the general concept of the thyroid-gut axis, a detailed molecular examination reveals how microbial metabolites and structural components can directly modulate thyroid hormone metabolism and immune function.

A particularly compelling area of investigation centers on the role of bacterial-derived endotoxins, specifically Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), in the pathogenesis of suppressed thyroid function, particularly in the context of non-thyroidal illness, also known as euthyroid sick syndrome.

The Inflammatory Cascade of Gut Permeability

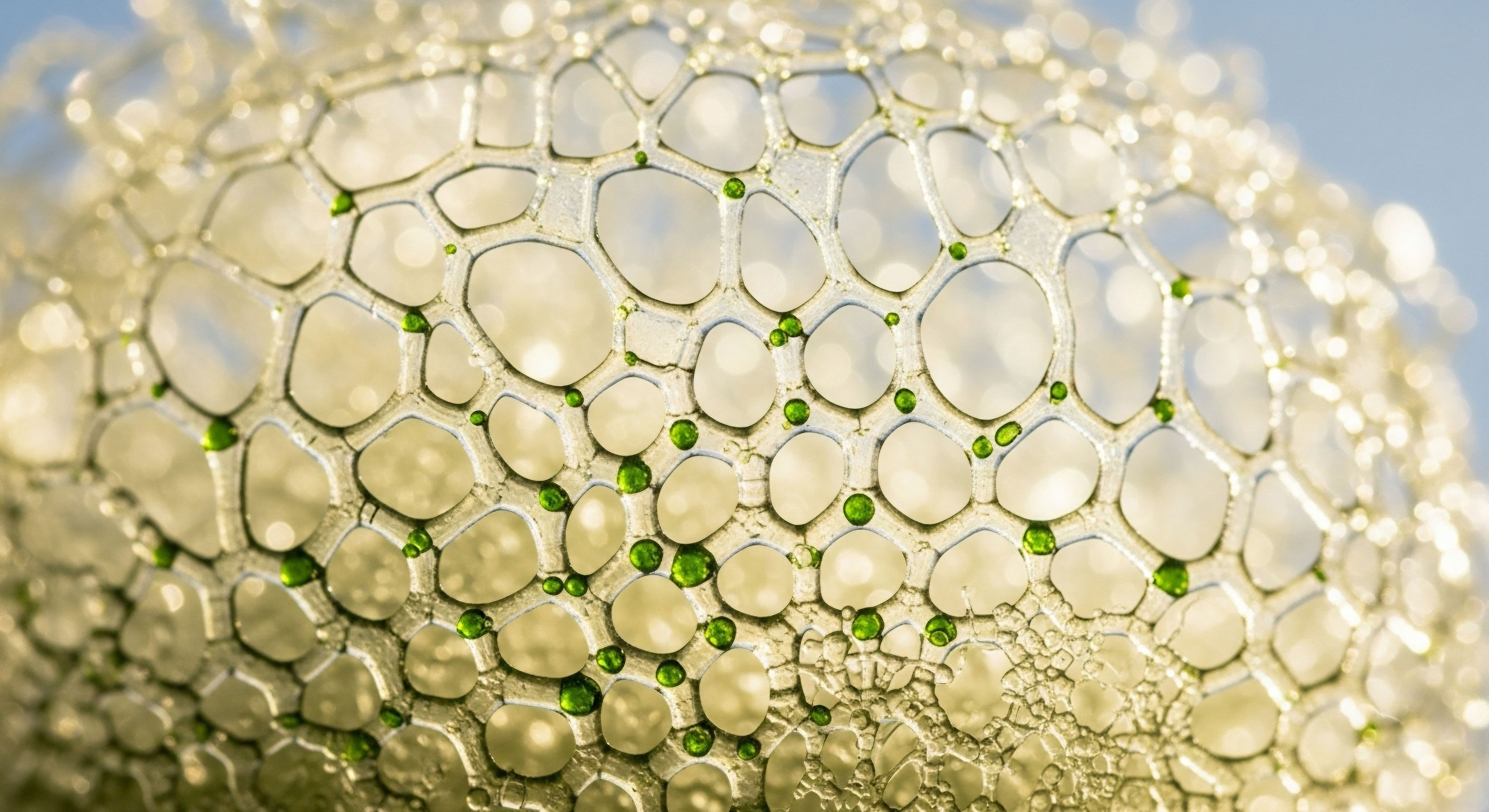

The intestinal epithelium forms a sophisticated, selectively permeable barrier that segregates the luminal contents of the gut from the host’s circulatory system. In a state of gut dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial commensal bacteria and an overgrowth of pathobionts, the integrity of this barrier can become compromised.

This condition, often termed increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut,” allows for the translocation of microbial components from the gut lumen into systemic circulation. Among the most immunogenic of these components is LPS, a major constituent of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

The presence of LPS in the bloodstream, a condition known as metabolic endotoxemia, is a potent trigger for the innate immune system. LPS binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune cells such as macrophages, initiating a powerful inflammatory signaling cascade.

This results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 (IL-1), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). This low-grade, chronic systemic inflammation becomes the backdrop against which critical physiological processes, including thyroid hormone conversion, are disrupted.

How Does Gut Inflammation Directly Suppress Active Thyroid Hormone?

The systemic inflammation driven by metabolic endotoxemia has profound and direct consequences for thyroid hormone metabolism. The primary enzymes responsible for the peripheral conversion of T4 to the biologically active T3 are the iodothyronine deiodinases, particularly type 1 deiodinase (D1), which is highly expressed in the liver, and type 2 deiodinase (D2). The pro-inflammatory cytokines released in response to LPS have been shown to be powerful inhibitors of D1 activity.

This inhibition creates a significant bottleneck in the T4-to-T3 conversion pathway. The liver, a primary site of T3 production, becomes less efficient at activating thyroid hormone. Consequently, circulating levels of active T3 fall, while levels of reverse T3 (rT3), an inactive metabolite, may rise as T4 is shunted down an alternative pathway.

This biochemical state ∞ characterized by normal or low TSH, normal T4, but low T3 ∞ is the clinical signature of euthyroid sick syndrome. The patient exhibits the classic symptoms of hypothyroidism because their cells are being starved of the active hormone, a direct downstream effect of gut-derived inflammation.

Lipopolysaccharide from gut bacteria can trigger a systemic inflammatory response that directly inhibits the enzymes responsible for converting inactive T4 into active T3 hormone.

A Systems Biology View of Autoimmune Thyroiditis

The implications of LPS-driven inflammation extend into the realm of autoimmunity. The chronic immune activation initiated by metabolic endotoxemia can contribute to the loss of immune tolerance, a key step in the development of autoimmune diseases like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. The GALT (Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue), which comprises approximately 70% of the body’s immune system, is at the front line of this interaction. Persistent stimulation of the GALT by translocating LPS can lead to a hyper-responsive immune state.

In genetically susceptible individuals, this can facilitate molecular mimicry, where the immune system mistakenly attacks thyroid tissue due to structural similarities between bacterial antigens and thyroid proteins. Furthermore, studies have identified altered microbial signatures in patients with Hashimoto’s, often showing a decreased abundance of beneficial, anti-inflammatory genera like Prevotella, and an increase in opportunistic pathogens.

This underscores a complex interplay where gut dysbiosis both suppresses active hormone conversion through inflammatory pathways and potentially contributes to the autoimmune destruction of the thyroid gland itself.

| Step | Biological Event | Key Molecules Involved | Clinical Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dysbiosis | An imbalance in the gut microbiome, with an overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria. | Reduced Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium; Increased opportunistic pathogens. | Foundation for intestinal barrier dysfunction. |

| 2. Increased Permeability | The tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells loosen, compromising the gut barrier. | Zonulin, Claudins. | Translocation of luminal contents into circulation. |

| 3. Metabolic Endotoxemia | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria enters the bloodstream. | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS). | Initiation of a systemic immune response. |

| 4. Immune Activation | LPS binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune cells, triggering an inflammatory cascade. | TLR4, NF-κB. | Release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. |

| 5. Cytokine Release | Systemic circulation of inflammatory messengers. | TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6. | Widespread low-grade inflammation. |

| 6. Deiodinase Inhibition | Pro-inflammatory cytokines directly suppress the activity of the Type 1 Deiodinase (D1) enzyme, primarily in the liver. | Type 1 Deiodinase (D1). | Impaired conversion of T4 to active T3. |

| 7. Hypothyroid Phenotype | Reduced levels of active T3 lead to symptoms of hypothyroidism despite potentially normal T4 and TSH levels. | Low Free T3, potentially high Reverse T3. | Fatigue, weight gain, cognitive slowing (Euthyroid Sick Syndrome). |

This detailed molecular pathway illustrates that the gut microbiome is not a passive bystander but an active participant in thyroid health. The composition of this microbial community holds direct regulatory power over the availability of active thyroid hormone, making the assessment and support of gut health a primary clinical consideration in the management of thyroid dysfunction and related metabolic disorders.

References

- Kresser, Chris. “Gut Microbes and Your Thyroid ∞ What’s the Connection?” Chris Kresser, 2023.

- Fröhlich, Eleonore, and Richard Wahl. “Thyroid-Gut-Axis ∞ How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function?” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 8, no. 10, 2019, p. 1679.

- Virili, Camilla, and Marco Centanni. “Does microbiota composition affect thyroid homeostasis?” Endocrine, vol. 49, no. 3, 2015, pp. 583-587.

- Yin, Jie, et al. “The relationships between the gut microbiota and its metabolites with thyroid diseases.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 13, 2022, p. 959269.

- Spaggiari, Giorgia, et al. “Major influences of the gut microbiota on thyroid metabolism ∞ a concise systematic review.” International Journal of Nutrology, vol. 16, no. 01, 2023, pp. e1-e7.

- Lauritano, E. C. et al. “Association between hypothyroidism and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 11, 2007, pp. 4180-4184.

Reflection

Your Biology Is a Conversation

The information presented here offers a map, tracing the intricate biochemical dialogue between the world within your gut and the energy that fuels your life. This is your personal biology, a dynamic and responsive system. The symptoms you feel are a part of this conversation, signals carrying valuable information about the state of your internal environment.

Knowledge of these pathways ∞ from microbial enzymes to inflammatory signals ∞ transforms your perspective. It moves you from a position of passive suffering to one of active participation in your own health narrative.

Consider the ecosystem within you. What is the quality of the environment you are cultivating? The food you consume, the stress you manage, the sleep you prioritize ∞ these are all inputs that shape the composition of your microbiome. This community, in turn, speaks directly to your endocrine system, influencing the very hormones that govern your vitality.

This understanding is the first, most crucial step. The path forward is one of partnership, both with your own body and with practitioners who recognize the profound interconnectedness of its systems. Your journey is unique, and armed with this knowledge, you are now equipped to ask deeper questions and seek solutions that honor the complexity of your whole being.

Glossary

thyroid hormone

gut microbiome

euthyroid sick syndrome

active thyroid hormone

intestinal sulfatase

thyroid function

secondary bile acids

bile acids

gut dysbiosis

thyroid-gut axis

bifidobacterium

lactobacillus

metabolic endotoxemia

pro-inflammatory cytokines