Fundamentals

The feeling can be deeply unsettling. You look in the mirror and see changes that feel alien to you ∞ persistent acne along the jawline, hair thinning in places you’ve always had it, or appearing in places you never did.

Your energy is a shadow of what it once was, and your monthly cycle, if it arrives at all, follows no predictable rhythm. These experiences are not isolated frustrations; they are signals from your body’s intricate communication network, the endocrine system. They are your biology asking for attention.

This journey into understanding your body begins with a single, powerful concept ∞ your hormonal state is a direct reflection of your internal environment. And the most profound influence on that environment is the food you consume every single day. The question of what dietary patterns best support androgen reduction is a personal one, and the answer lies in understanding the conversation between your plate and your hormones.

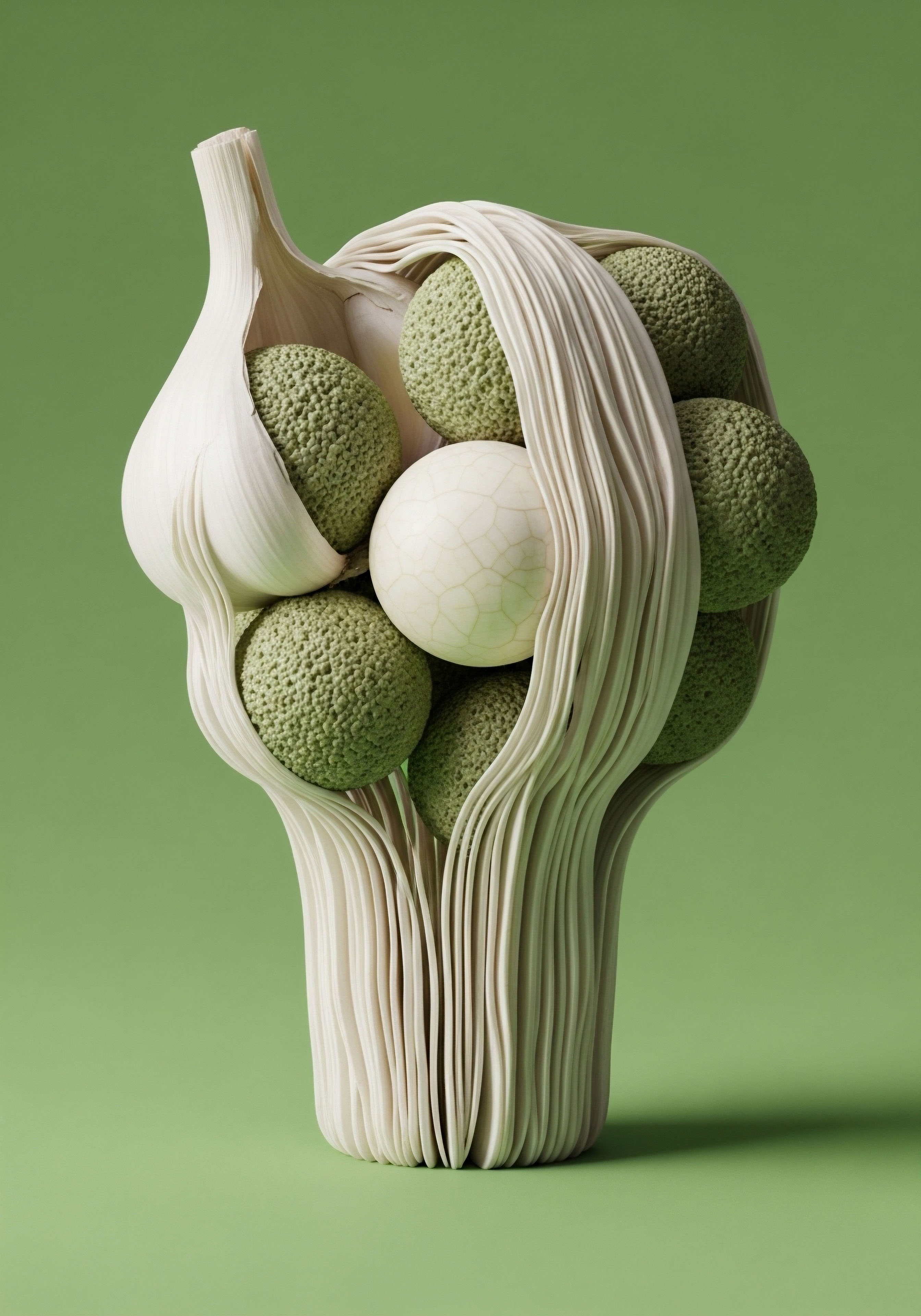

Your body is a marvel of biological engineering, and at the heart of its operations lies a delicate balance. Androgens, a group of hormones that includes testosterone, are often associated with male characteristics, yet they are vital for everyone, contributing to bone health, muscle mass, and libido.

The issue arises when their levels become elevated, creating a state of hyperandrogenism. This hormonal imbalance is a key feature in conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), which affects millions of women. The symptoms you experience are the downstream effects of this imbalance. Your body is not broken; it is responding predictably to a set of internal cues. Our goal is to change those cues, to recalibrate the system by addressing one of the most powerful levers we have ∞ nutrition.

Understanding the link between your diet and your hormones is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

The Central Role of Insulin

To understand how diet influences androgens, we must first look at another hormone, one that acts as a master conductor of your metabolic orchestra ∞ insulin. Produced by the pancreas, insulin’s primary job is to act like a key, unlocking your cells to allow glucose (sugar) from your bloodstream to enter and be used for energy.

This is a beautiful and efficient system when it is working correctly. When you eat a meal, particularly one containing carbohydrates, your blood glucose levels rise. Your pancreas releases insulin in response, which shuttles that glucose into your cells, and your blood sugar returns to a stable baseline.

A challenge occurs when cells become less responsive to insulin’s signal. This is a condition known as insulin resistance. Imagine the locks on your cells have become rusty. The key (insulin) still fits, but it takes more and more effort to turn it.

Your pancreas, sensing that glucose is still high in the blood, compensates by pumping out even more insulin. This leads to a state of chronically high insulin levels, or hyperinsulinemia. This is where the connection to androgens becomes critically clear. The elevated levels of insulin send a powerful signal to the ovaries, prompting them to produce more testosterone.

Simultaneously, high insulin levels travel to the liver and suppress the production of a crucial protein called Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG acts like a hormonal taxi service, binding to testosterone in the bloodstream and keeping it inactive. When SHBG levels drop, more testosterone is left to roam free in its unbound, biologically active form. This “free androgen index” is often what drives the most noticeable symptoms. Therefore, managing insulin is the cornerstone of managing androgens.

Foundational Dietary Principles

With this understanding of the insulin-androgen connection, the logic behind dietary recommendations becomes clear. The primary objective is to create a metabolic environment that promotes stable blood sugar and insulin sensitivity. This involves shifting the focus toward dietary patterns that provide a slow, steady release of energy, rather than sharp spikes and crashes.

Focusing on Low-Glycemic Foods

The glycemic index (GI) is a tool that ranks carbohydrate-containing foods by how much they raise blood glucose levels after being eaten. High-GI foods, like white bread, sugary cereals, and potatoes, are rapidly digested and cause a quick surge in blood sugar and a corresponding large release of insulin.

Low-GI foods, such as non-starchy vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, are digested more slowly, leading to a gentler rise in blood sugar and a more moderate insulin response. Adopting a low-glycemic dietary pattern helps to break the cycle of hyperinsulinemia that drives androgen production. This means building meals around fiber-rich vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats, with mindfully chosen whole-food carbohydrate sources.

Embracing Anti-Inflammatory Eating

Chronic low-grade inflammation is another key factor that contributes to insulin resistance and hormonal imbalance. Many of the foods that are high on the glycemic index are also pro-inflammatory. Processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats can trigger an inflammatory response in the body, further impairing insulin signaling and exacerbating hormonal symptoms.

An anti-inflammatory diet, rich in antioxidants and beneficial compounds, helps to quell this internal fire. This includes a colorful array of vegetables and fruits, omega-3 fatty acids from sources like fatty fish, and healthy fats from olives, avocados, and nuts. Spices like turmeric and ginger also possess potent anti-inflammatory properties. The Mediterranean diet is an excellent example of an eating pattern that is both low-glycemic and anti-inflammatory.

The Importance of Nutrient Density

When your body is under metabolic stress, providing it with the micronutrients it needs to function optimally is essential. Certain nutrients play a direct role in hormone health. Magnesium, found in leafy greens, nuts, and seeds, is involved in insulin signaling.

Zinc, present in shellfish, legumes, and seeds, is important for ovarian function and can help reduce some androgen-related symptoms. B vitamins are crucial for energy metabolism and hormone production. Focusing on whole, unprocessed foods ensures a rich supply of these vital nutrients, supporting your body’s ability to heal and rebalance.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational principles of insulin management, we can now examine the specific architectural frameworks of dietary patterns that have been clinically studied for their effects on androgen reduction. These are not rigid “diets” in the conventional sense, but rather flexible, evidence-based templates for constructing a way of eating that supports endocrine health.

The primary goal remains the same ∞ to mitigate hyperinsulinemia and reduce inflammation. However, these patterns offer structured approaches to achieve that goal, each with its own unique emphasis.

A Deeper Look at Key Dietary Patterns

Three dietary patterns consistently emerge in the clinical literature as beneficial for conditions of androgen excess ∞ the Low-Glycemic Index Diet, the Mediterranean Diet, and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. Each of these patterns shares common ground in its emphasis on whole foods and its ability to improve insulin sensitivity, yet they offer slightly different paths to the same destination.

The Low-Glycemic Index (LGI) Diet

The LGI diet is perhaps the most direct approach to controlling the insulin response. Its core principle is the deliberate selection of carbohydrates that have a minimal impact on blood glucose levels. This requires a conscious shift away from high-GI foods and toward those with a lower GI value.

A study published in 2024 specifically found that a low-glycemic diet with anti-inflammatory elements led to a significant decrease in total testosterone and the free androgen index in overweight women with hyperandrogenism.

- Core Components ∞ The diet is built upon non-starchy vegetables (like broccoli, peppers, and leafy greens), legumes (lentils, chickpeas), and certain fruits (berries, cherries). Protein sources are lean, and fats are healthy. When grains are included, they are intact whole grains like quinoa or steel-cut oats.

- Mechanism of Action ∞ By preventing sharp spikes in blood glucose, the LGI diet reduces the demand on the pancreas to produce large amounts of insulin. This directly interrupts the primary mechanism driving ovarian androgen overproduction and the suppression of SHBG. Over time, this can lead to improved insulin sensitivity, making the body’s cells more responsive to the hormone.

The Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet is less about specific glycemic values and more about an overall pattern of eating that is rich in beneficial nutrients and low in inflammatory triggers. It is characterized by a high intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and whole grains, with olive oil as the principal source of fat.

Fish and poultry are consumed in moderation, while red meat and dairy are limited. Research from Johns Hopkins Medicine highlights the Mediterranean diet as a powerful tool to address the systemic inflammation often seen in individuals with PCOS.

- Core Components ∞ Abundant plant foods, liberal use of extra virgin olive oil, high consumption of fish (especially fatty fish rich in omega-3s), and moderate consumption of wine with meals.

- Mechanism of Action ∞ The diet’s power lies in its synergy. The high fiber content slows sugar absorption. The abundance of monounsaturated fats from olive oil and omega-3s from fish has potent anti-inflammatory effects, which can improve insulin receptor function. The rich supply of antioxidants from colorful plants helps to combat oxidative stress, a partner to inflammation. This multi-pronged approach helps to create a favorable metabolic environment for hormonal balance.

The DASH Diet

The DASH diet was originally developed to combat high blood pressure, but its principles are highly effective for improving metabolic health as well. It emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products and is low in saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol. It also includes whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts.

A systematic review found that the DASH diet can lead to a reduction in insulin resistance and an improvement in abdominal fat deposition, both of which are linked to androgen levels.

- Core Components ∞ High in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. It specifically encourages low-fat or fat-free dairy and is lower in sodium than a typical Western diet.

- Mechanism of Action ∞ Like the other patterns, the DASH diet is rich in fiber and nutrients. Its emphasis on limiting sodium and increasing potassium, calcium, and magnesium intake may have additional benefits for cellular function and blood pressure regulation, which are often comorbid concerns in individuals with metabolic syndrome. The overall pattern is one that naturally supports stable blood sugar and reduces metabolic stress.

Adopting an evidence-based dietary pattern provides a structured yet flexible path toward hormonal recalibration.

Comparative Analysis of Dietary Patterns

To better visualize the similarities and differences between these effective dietary patterns, the following table provides a comparative overview.

| Dietary Component | Low-Glycemic Index (LGI) Diet | Mediterranean Diet | DASH Diet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Controlling blood glucose and insulin response by selecting specific carbohydrate types. | Overall pattern rich in anti-inflammatory fats, fiber, and antioxidants. | Reducing blood pressure and improving metabolic markers through a nutrient-dense, low-sodium pattern. |

| Key Foods | Non-starchy vegetables, legumes, berries, lean protein, healthy fats, intact whole grains. | Olive oil, fatty fish, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, whole grains. | Fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, whole grains, lean protein, nuts, seeds. |

| Foods to Limit | Refined grains (white bread, pasta), sugary drinks, processed snacks, high-GI fruits and vegetables. | Red meat, processed foods, refined sugars, butter. | Saturated fats, full-fat dairy, sugary beverages, high-sodium processed foods. |

| Clinical Evidence for Androgen Reduction | Directly shown to reduce total and free testosterone by managing insulin. | Reduces inflammation and insulin resistance, indirectly supporting androgen balance. | Improves insulin sensitivity and reduces central adiposity, contributing to lower androgen levels. |

The Role of the Gut Microbiome

An emerging area of research is the connection between the gut microbiome ∞ the trillions of bacteria residing in your digestive tract ∞ and hormonal health. The composition of your gut bacteria can influence inflammation, nutrient absorption, and even the metabolism of hormones.

A diet high in processed foods and low in fiber can lead to a state of gut dysbiosis, where less beneficial bacteria proliferate. This can increase gut permeability (“leaky gut”), allowing inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream and contribute to systemic inflammation and insulin resistance.

All three of the dietary patterns discussed above are beneficial for the gut microbiome due to their high fiber content. Fiber acts as a prebiotic, providing fuel for beneficial gut bacteria. A healthy gut lining and a balanced microbiome are another layer of support in the quest for hormonal harmony.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of dietary influence on androgen modulation requires a descent into the molecular machinery of the cell. The clinical manifestations of hyperandrogenism are the macroscopic expression of a complex interplay between genetic predispositions, metabolic signals, and endocrine feedback loops. The dietary patterns discussed previously are effective because they modulate these fundamental biological pathways.

Here, we will dissect the intricate mechanisms through which nutrition recalibrates the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, influences steroidogenesis at the ovarian level, and alters the bioavailability of androgens in circulation.

Insulin’s Molecular Crosstalk with Ovarian Steroidogenesis

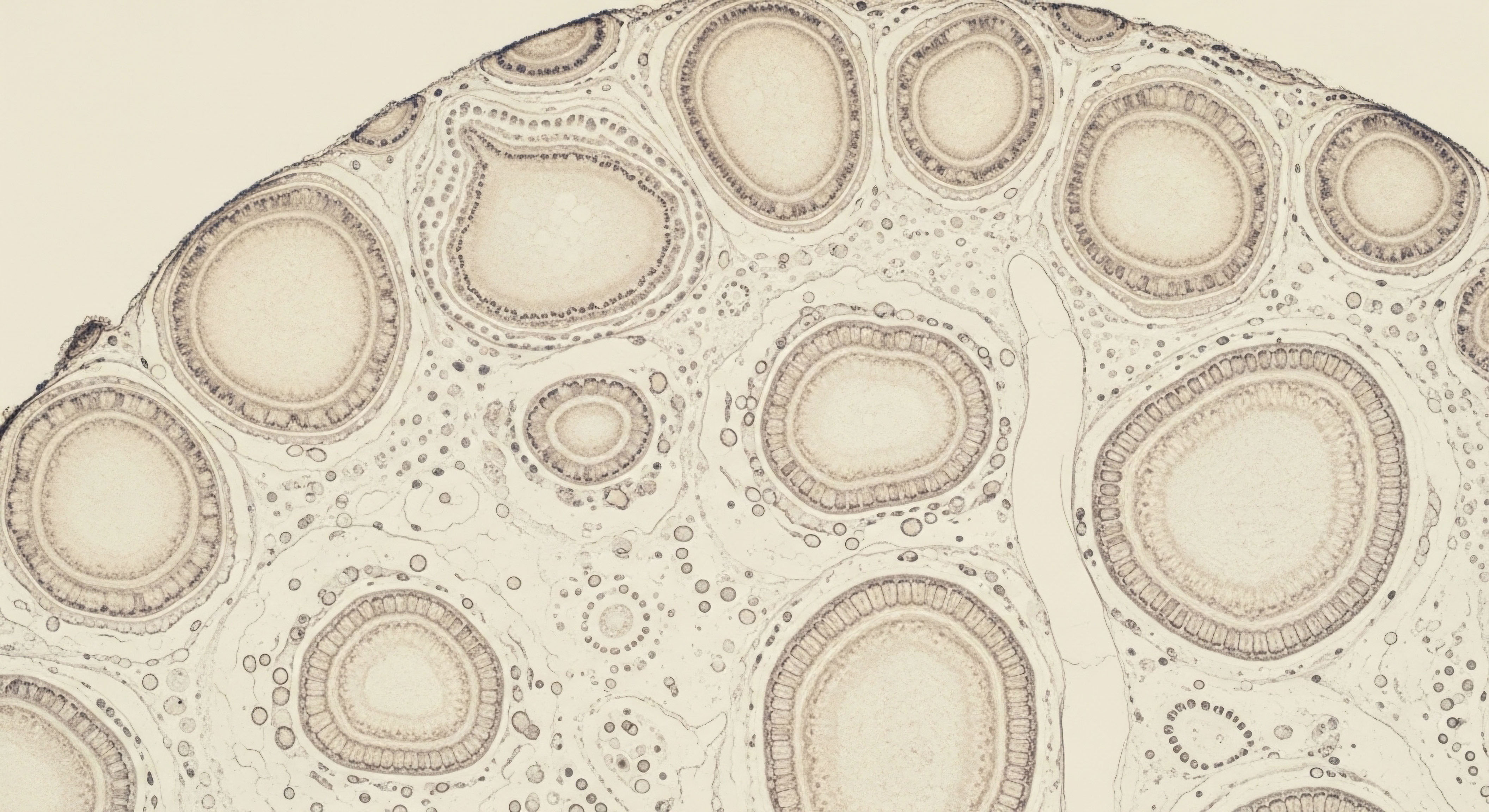

The link between hyperinsulinemia and hyperandrogenism is not merely correlational; it is causal, rooted in the molecular biology of the ovarian theca cells. These cells are responsible for producing androgens, primarily androstenedione and testosterone, under the stimulation of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) from the pituitary gland. Insulin acts as a potent co-gonadotropin, amplifying the effects of LH on these cells. The mechanism is multifaceted:

- Upregulation of Steroidogenic Enzymes ∞ Insulin directly activates the expression and activity of key enzymes in the androgen synthesis pathway. One of the most critical is CYP17A1 (17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase), the rate-limiting enzyme for androgen production. Insulin, through its receptor and subsequent signaling cascades (primarily the PI3K/Akt pathway), enhances the transcription of the CYP17A1 gene. This effectively accelerates the conversion of progesterone and pregnenolone into androgens.

- Synergy with LH Signaling ∞ Insulin receptors and LH receptors are both present on theca cells. When insulin binds to its receptor, it can trigger downstream signaling molecules that are also used by the LH receptor pathway. This creates a synergistic effect, meaning the combined stimulus from both insulin and LH results in a far greater androgen output than either hormone could achieve alone.

- Suppression of SHBG Synthesis ∞ At the hepatic level, insulin exerts a powerful inhibitory effect on the production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). The transcription of the SHBG gene is suppressed by high insulin levels, likely mediated through the downregulation of key liver-enriched transcription factors like HNF-4α. The resulting decrease in circulating SHBG means a higher proportion of total testosterone exists in its unbound, biologically active state, capable of binding to androgen receptors throughout the body and exerting its effects.

Dietary interventions that lower ambient insulin levels ∞ such as low-glycemic load diets ∞ directly target these three molecular leverage points. By reducing the chronic insulin stimulus, these diets downregulate the expression of steroidogenic enzymes, reduce the synergistic amplification of the LH signal, and allow for the recovery of hepatic SHBG synthesis.

The Influence of Dietary Components on Inflammatory Pathways

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a key pathophysiological feature of metabolic dysfunction and acts as a potent amplifier of insulin resistance. Dietary patterns influence this inflammatory state at a molecular level, primarily through the modulation of the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) signaling pathway.

How Do Dietary Choices Impact Inflammation?

Certain dietary components can either promote or inhibit the activation of this pathway. For instance, a high intake of saturated fatty acids and advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which are abundant in processed and high-sugar foods, can activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on immune cells.

This activation triggers a cascade that leads to the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, the inhibitor of NF-κB. Once freed, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus and initiates the transcription of a host of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6.

These cytokines can then interfere with insulin signaling in peripheral tissues like muscle and fat, inducing insulin resistance by phosphorylating insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at inhibitory serine sites. This creates a vicious cycle where inflammation drives insulin resistance, which drives hyperinsulinemia, which in turn promotes more inflammation.

Conversely, components of anti-inflammatory diets, like the Mediterranean diet, can disrupt this cycle. Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) can be converted into specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) like resolvins and protectins, which actively terminate the inflammatory response.

Polyphenols, found in colorful plants, olive oil, and green tea, can directly inhibit the activation of NF-κB and scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), reducing the oxidative stress that often accompanies inflammation. By mitigating the inflammatory cascade, these dietary patterns help preserve insulin sensitivity, thereby indirectly contributing to the reduction of androgen excess.

Nutritional interventions achieve androgen reduction by fundamentally altering the molecular signals that govern hormone synthesis and bioavailability.

Detailed Mechanisms of Action for Specific Nutrients

Beyond broad dietary patterns, specific nutrients and food components have been investigated for their roles in modulating androgen metabolism. The table below details some of these interactions.

| Nutrient/Component | Source | Proposed Mechanism of Action for Androgen Reduction | Supporting Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Fiber (Soluble & Insoluble) | Legumes, oats, psyllium, vegetables, whole grains | Slows glucose absorption, reducing postprandial insulin spikes. Increases SHBG levels. Modulates gut microbiota to reduce systemic inflammation. | High |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA/DHA) | Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), fish oil supplements | Reduces inflammation via production of resolvins and inhibition of NF-κB. Improves insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. May directly lower androgen levels. | Moderate to High |

| Magnesium | Leafy greens, nuts, seeds, dark chocolate | Acts as a cofactor for multiple enzymes in the insulin signaling pathway. Improves insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake. | Moderate |

| Zinc | Oysters, red meat, poultry, beans, nuts | May inhibit 5-alpha reductase, the enzyme that converts testosterone to the more potent DHT. Also has anti-inflammatory properties. | Moderate |

| Phytoestrogens (e.g. Isoflavones) | Soy products (tofu, edamame), flaxseeds | Weakly bind to estrogen receptors, potentially modulating HPG axis feedback. May increase SHBG production. Some studies suggest a mild anti-androgenic effect. | Low to Moderate (Controversial) |

| Spearmint Tea (Mentha spicata) | Spearmint leaves | Clinical studies in women with PCOS have shown it can significantly reduce free and total testosterone levels, potentially through inhibition of testosterone synthesis or enhancement of its clearance. | Moderate (for symptomatic relief) |

Can a High Protein Diet Help with Androgen Reduction?

The role of macronutrient ratios, particularly high-protein diets, is a subject of ongoing investigation. Some studies suggest that higher protein intake can enhance satiety and preserve lean body mass during weight loss, which is beneficial for metabolic health. The thermic effect of food is also higher for protein, meaning more calories are burned during its digestion.

However, the direct impact on androgen levels appears to be primarily mediated by the caloric deficit and subsequent weight loss, rather than the protein content itself. Some research even suggests that very high protein intake in certain contexts could have complex effects on the HPG axis.

Therefore, a moderate increase in protein from high-quality sources within a balanced, low-glycemic, and anti-inflammatory framework is a reasonable strategy, but extreme high-protein diets may not offer additional androgen-reducing benefits beyond their effect on weight management.

References

- Kłósek, M. et al. “Reduction in the Free Androgen Index in Overweight Women After Sixty Days of a Low Glycemic Diet.” Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny, vol. 75, no. 1, 2024, pp. 65-74.

- Barrea, L. et al. “Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Hyperandrogenism Mediate the Link between Poor Diet Quality and Ovarian Dysmorphology in Reproductive-Aged Women.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 11, 2021, p. 3786.

- Shang, Y. et al. “Dietary Modification for Reproductive Health in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 735954.

- Chacko, S. A. et al. “Relations of Dietary Magnesium Intake to Fasting Insulin, Glucose, and Insulin Resistance.” Diabetes Care, vol. 33, no. 2, 2010, pp. 304-10.

- Moran, L. J. et al. “Dietary Composition in the Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review to Inform Evidence-Based Guidelines.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, vol. 113, no. 4, 2013, pp. 520-45.

- González, F. “Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ Underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction.” Steroids, vol. 77, no. 4, 2012, pp. 300-5.

- Poretsky, L. et al. “The Insulin-Related Ovarian Regulatory System in Health and Disease.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 20, no. 4, 1999, pp. 535-82.

- Grant, P. “Spearmint herbal tea has significant anti-androgen effects in polycystic ovarian syndrome. A randomized controlled trial.” Phytotherapy Research, vol. 24, no. 2, 2010, pp. 186-8.

- Cutler, D. A. et al. “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 377, no. 1, 2017, pp. 55-65.

- Liepa, G. U. et al. “A review of the effects of nuts on appetite, food intake, metabolism, and body weight.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 86, no. 5, 2007, pp. 1588-96.

Reflection

You have now traveled through the intricate biological landscape that connects your plate to your hormonal health. You have seen how a simple meal can initiate a cascade of molecular signals that echo throughout your entire system. This knowledge is powerful.

It shifts the narrative from one of passive suffering to one of active participation in your own well-being. The symptoms you have been experiencing are not a life sentence; they are a conversation. Your body has been speaking to you, and now you are better equipped to understand its language.

The path forward is one of personalization and self-compassion. The dietary patterns and principles outlined here are not rigid prescriptions but guiding stars. They provide a framework, a starting point from which to build a way of eating that feels sustainable, enjoyable, and nourishing for you. Your journey will be unique.

It will involve listening to your body’s feedback, observing how you feel, and making adjustments along the way. Consider this knowledge the first, most important step. The next is to apply it, patiently and consistently, and perhaps in partnership with a healthcare professional who can help you navigate the specifics of your individual biology.

You hold the power to change the conversation with your body, to move from a state of imbalance toward one of vitality and function. The potential for recalibration lies within you.

Glossary

androgen reduction

dietary patterns

polycystic ovary syndrome

hyperandrogenism

blood glucose levels

blood sugar

insulin resistance

high insulin levels

free androgen index

shbg

insulin sensitivity

blood glucose

insulin response

insulin signaling

anti-inflammatory diet

omega-3 fatty acids

mediterranean diet

low-glycemic diet

dash diet

androgen levels

gut microbiome

cyp17a1