Fundamentals

The experience of perimenopause begins within your own body, a profound shift in its internal communication system. You may notice changes in your energy, your sleep, your moods, and your monthly cycle. These are tangible signals of a natural biological transition, one driven by fluctuating levels of key hormones, primarily estrogen and progesterone.

Providing your body with specific nutritional building blocks is a direct way to support its internal equilibrium during this time. Your dietary choices become a foundational tool for navigating this change with vitality.

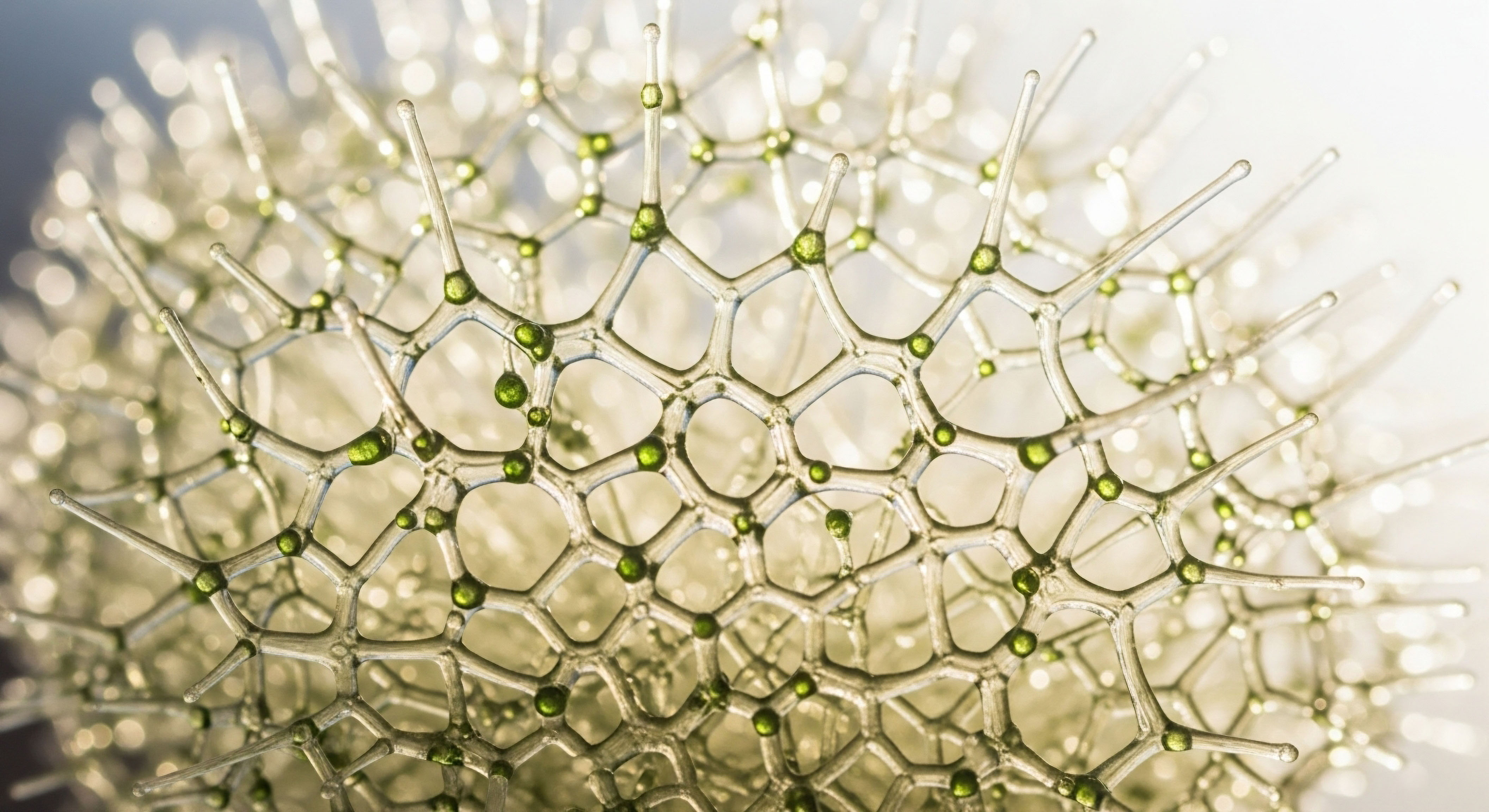

Think of your endocrine system as a complex signaling network. Hormones are the messengers, carrying instructions to cells throughout your body. During perimenopause, the production of these messengers becomes less predictable. A well-constructed diet supplies the raw materials needed to build these molecules and helps the body process them effectively, bringing a greater sense of stability to the entire system.

Architects of Cellular Communication

Certain foods contain compounds that can gently and beneficially interact with your body’s hormonal pathways. Integrating these into your daily meals provides a consistent source of support for your changing biology.

Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds with a molecular structure similar to the body’s own estrogen. This similarity allows them to bind to estrogen receptors, creating a mild balancing effect. When your natural estrogen levels dip, phytoestrogens can provide a subtle lift; when levels are high, they can occupy receptors and buffer the impact. This helps to smooth out the fluctuations that contribute to symptoms like hot flashes.

- Flaxseeds ∞ Ground flaxseeds are a potent source of lignans, a primary class of phytoestrogens.

- Soy ∞ Foods like tofu, tempeh, and edamame contain isoflavones, another well-studied type of phytoestrogen.

- Legumes ∞ Chickpeas and lentils offer both phytoestrogens and a wealth of fiber, contributing to hormonal and digestive health.

Reinforcing Your Body’s Framework

The decline in estrogen directly affects bone density. Estrogen helps to regulate the constant process of bone remodeling, where old bone is broken down and new bone is formed. As estrogen levels wane, this balance can tip towards greater bone loss, increasing the long-term risk of osteoporosis. Therefore, providing the essential minerals for bone architecture becomes a primary objective.

A consistent intake of calcium and vitamin D is fundamental to maintaining skeletal strength through the perimenopausal transition and beyond.

Calcium is the primary mineral that gives bones their hardness and structure. Vitamin D is essential for your body to absorb that calcium from your diet and deposit it into your skeleton. Without sufficient vitamin D, dietary calcium cannot be used effectively. These two nutrients work as a team, making their combined intake a critical dietary focus.

Fueling Metabolic Stability

Hormonal fluctuations can also disrupt your body’s management of blood sugar, leading to energy crashes and mood swings. Dietary fiber is a key regulator of this system. It slows the absorption of sugar from the digestive tract into the bloodstream, promoting more stable blood sugar and insulin levels. This metabolic evenness translates into more consistent energy and a more stable mood throughout the day.

Furthermore, fiber plays a direct role in hormone regulation by supporting efficient digestion and elimination. The gut is a primary site for processing and clearing used hormones from the body. A high-fiber diet ensures this process runs smoothly, preventing the recirculation of excess estrogens that can contribute to hormonal imbalance.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational nutrients, a more sophisticated dietary approach to perimenopause involves understanding the intricate connections between your gut, your inflammatory status, and your endocrine system. The foods you consume directly influence the microbial ecosystem in your intestines, which in turn has a profound impact on how your body metabolizes and balances hormones. This is a systems-based approach, recognizing that hormonal health is deeply interconnected with other core biological processes.

The Gut-Hormone Connection

Your gastrointestinal tract is home to a complex community of microorganisms known as the gut microbiome. Within this community resides a specific collection of bacteria with a very specialized job ∞ metabolizing estrogens. This subset of microbes, collectively called the estrobolome, produces an enzyme that reactivates processed estrogen in the gut, allowing it to re-enter circulation. The health and diversity of your estrobolome directly modulate your body’s circulating estrogen levels.

A diet rich in prebiotic fiber and probiotics cultivates a healthy and diverse microbiome, which supports a balanced estrobolome. Prebiotic fibers, found in foods like garlic, onions, and asparagus, are indigestible fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria. Probiotic foods, such as yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut, introduce live beneficial bacteria directly into the system. Together, they create an internal environment where hormonal metabolism can function optimally.

Your gut microbiome acts as a central command center for hormone regulation, directly influencing estrogen levels through a specialized set of bacteria.

How Does Diet Influence Inflammatory Pathways?

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a common physiological stressor that can amplify perimenopausal symptoms. The hormonal shifts of this period can themselves contribute to inflammation, and a pro-inflammatory diet can add fuel to the fire. An anti-inflammatory eating pattern helps to quiet this underlying reactivity, which can soothe symptoms like joint pain, mood disturbances, and even the intensity of hot flashes.

The mechanism involves specific food components that modulate the body’s inflammatory signaling pathways. Omega-3 fatty acids, for example, are precursors to powerful anti-inflammatory molecules called resolvins and protectins. Conversely, certain fats promote the production of pro-inflammatory messengers.

| Type of Fat | Primary Sources | Role in Hormonal and Inflammatory Health |

|---|---|---|

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), flaxseeds, chia seeds, walnuts | Actively reduces inflammation, supports brain health, and provides building blocks for hormone production. |

| Monounsaturated Fats | Olive oil, avocados, almonds | Supports cardiovascular health and has neutral to anti-inflammatory effects. |

| Saturated Fats | Red meat, full-fat dairy, coconut oil | Should be consumed in moderation as high intake can contribute to inflammation and affect cholesterol levels. |

| Trans Fats | Processed baked goods, fried foods | Strongly pro-inflammatory and detrimental to cardiovascular health; should be avoided. |

Targeted Micronutrients for Symptom Management

Beyond broad food categories, specific vitamins and minerals play targeted roles in mitigating some of the most challenging symptoms of perimenopause. Ensuring an adequate supply of these micronutrients can provide another layer of support for your neurological and physiological well-being.

| Nutrient | Symptom-Specific Role | Rich Food Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium | Supports the nervous system to promote relaxation and improve sleep quality. It can also help with muscle tension and mood stability. | Leafy greens (spinach, Swiss chard), nuts (almonds, cashews), seeds (pumpkin seeds), dark chocolate. |

| B Vitamins (B6, B12) | Essential for neurotransmitter synthesis, including serotonin and dopamine, which regulate mood. They support cognitive function and can help with brain fog. | Lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, legumes, nutritional yeast. |

| Iron | Crucial for women experiencing heavier menstrual bleeding, as depletion can lead to fatigue, weakness, and anemia. | Lean red meat, poultry, fish, lentils, beans, fortified cereals. |

Academic

A highly specific and potent dietary intervention for modulating female hormonal balance involves the targeted consumption of brassica vegetables. The clinical significance of this food family, which includes broccoli, cauliflower, kale, and Brussels sprouts, extends far beyond their basic nutritional profile.

Their value lies in their unique content of glucosinolates, particularly glucobrassicin, which upon digestion yields bioactive compounds like indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and its primary metabolite, 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM). These compounds are powerful modulators of estrogen metabolism, primarily through their influence on hepatic detoxification pathways.

Hepatic Estrogen Metabolism a Two Phase Process

The liver is the primary site for the biotransformation and detoxification of steroid hormones, including estrogens. This process occurs in two distinct phases, and the balance between them is critical for maintaining hormonal health. The objective is to convert fat-soluble estrogens into water-soluble forms that can be safely excreted from the body.

Phase I metabolism involves a group of enzymes known as the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family. These enzymes hydroxylate estrogens, creating different estrogen metabolites. The two primary pathways are:

- The 2-hydroxylation pathway (CYP1A1/1A2) ∞ This pathway produces 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1), which is considered a “beneficial” or “weak” estrogen metabolite. It has minimal estrogenic activity and is associated with lower risks of hormone-sensitive conditions.

- The 16α-hydroxylation pathway (CYP3A4) ∞ This pathway produces 16α-hydroxyestrone (16α-OHE1), a much more potent and biologically active metabolite. Elevated levels of 16α-OHE1 are linked to increased estrogenic stimulation of tissues.

Phase II metabolism involves conjugation, where enzymes attach molecules like glucuronic acid or sulfate to the Phase I metabolites, rendering them water-soluble and ready for excretion via urine or bile.

The ratio of 2-OHE1 to 16α-OHE1 is a key biomarker of estrogenic activity and hormonal risk, with a higher ratio being favorable.

How Do Cruciferous Vegetables Influence Estrogen Pathways?

The compounds I3C and DIM derived from brassica vegetables exert a profound influence on this metabolic system. Their primary mechanism of action is the selective upregulation of Phase I enzymes, particularly those in the favorable 2-hydroxylation pathway.

By increasing the activity of CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 enzymes, I3C and DIM actively steer estrogen metabolism away from the potent 16α-hydroxylation pathway and toward the production of the less estrogenic 2-OHE1 metabolite. This shift in the metabolic ratio is a powerful mechanism for reducing the overall estrogenic burden on the body. This biochemical recalibration can be particularly beneficial during perimenopause, when fluctuating and sometimes high estrogen levels can contribute to symptoms and increase tissue sensitivity.

Consuming brassica vegetables regularly provides the substrates for this beneficial metabolic shift. Steaming or lightly cooking these vegetables can enhance the bioavailability of these compounds. This dietary strategy represents a direct, evidence-based method for supporting the body’s innate capacity to maintain a healthy hormonal environment through the modulation of specific enzymatic pathways. This is a clear example of how food acts as biological information, providing precise instructions to the body’s metabolic machinery.

References

- Erdélyi, A. et al. “The importance of nutrition in menopause and perimenopause ∞ A review.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 24, 2023, p. 5148.

- Desmawati, D. and D. Sulastri. “Phytoestrogens and their health effect.” Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, vol. 7, no. 3, 2019, pp. 495-499.

- Baker, J. M. et al. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Min, Y. et al. “Indole-3-carbinol, a plant-derived compound, stimulates the proliferation of human-colorectal-cancer-derived Caco-2 cells by upregulating the expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor.” Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, vol. 22, no. 11, 2011, pp. 1046-1052.

- Bradlow, H. L. et al. “2-hydroxyestrone ∞ the ‘good’ estrogen.” Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 150, no. Supplement, 1996, pp. S259-S265.

- Silvestrini, A. et al. “The role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis.” Endocrine, vol. 60, no. 1, 2018, pp. 18-25.

- Parazzini, F. et al. “Dietary components and menopausal symptoms in a cohort of Italian women.” Climacteric, vol. 21, no. 2, 2018, pp. 185-190.

- Simkin-Silverman, L. R. et al. “Effects of a low-fat diet on hot flashes in a 2-year randomized controlled trial.” Menopause, vol. 14, no. 5, 2007, pp. 835-843.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map, detailing the biological terrain of perimenopause and the ways nutrition can act as a guide. It connects the feelings within your body to the cellular processes that drive them. This knowledge transforms abstract symptoms into clear signals, providing a language to understand your body’s needs.

The true work begins now, in your own kitchen and with your own choices. Consider this an invitation to begin a personal experiment, one of listening to your body with a new level of awareness. Each meal is an opportunity to provide support, to observe the response, and to refine your own unique protocol for vitality.

This journey is about reclaiming a collaborative relationship with your own biology, using informed choices to steer yourself toward a state of resilient well-being.

Glossary

estrogen levels

phytoestrogens

dietary fiber

estrobolome

anti-inflammatory eating

omega-3 fatty acids

hormonal balance

hepatic detoxification

estrogen metabolism