Fundamentals

The experience of living with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) often involves a profound sense of disconnection from one’s own body. The symptoms, which can range from persistent weight gain and metabolic disruption to irregular menstrual cycles and changes in skin and hair, are tangible data points.

They are your body’s method of communicating a significant change in its internal environment. Understanding the language of these signals is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of agency over your health. At the center of this conversation is a powerful signaling molecule, a hormone that governs energy and influences reproductive function with remarkable precision ∞ insulin.

Insulin’s primary role is to manage blood glucose, shuttling it from the bloodstream into cells where it can be used for energy. Think of it as a key designed to unlock your body’s cells. In a state of insulin resistance, a condition central to the physiology of PCOS, the locks on the cells become less responsive to the key.

Your pancreas, the organ that produces insulin, compensates by releasing more and more of it to get the job done. This creates a state of chronically elevated insulin, known as hyperinsulinemia. This elevated hormonal signal becomes the driving force behind many of the symptoms you may be experiencing.

The core of PCOS management begins with understanding and addressing the body’s response to insulin.

The Insulin Androgen Connection

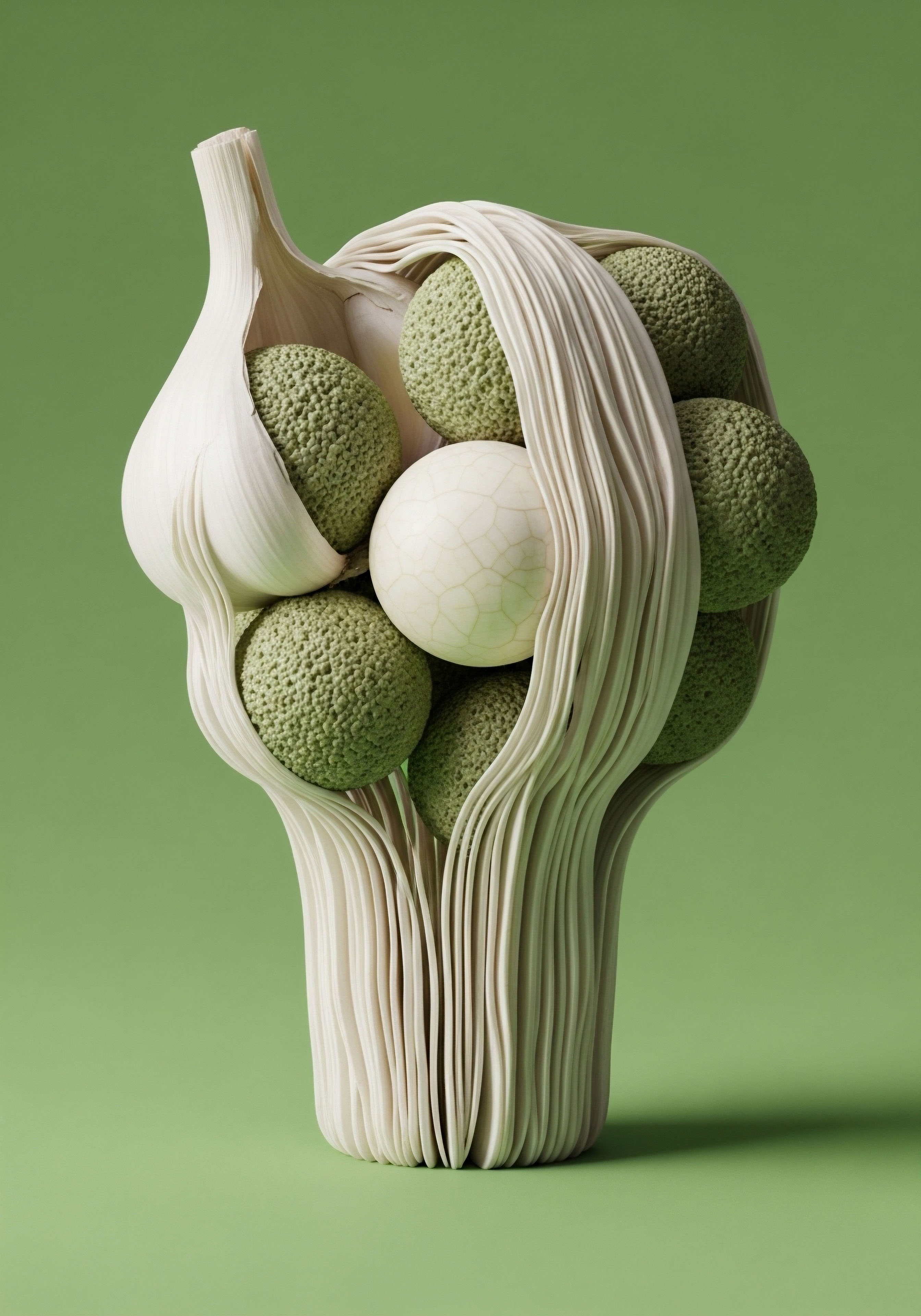

The ovaries are uniquely sensitive to the effects of insulin. When insulin levels are persistently high, they directly stimulate the theca cells within the ovaries to produce an excess of androgens, such as testosterone. This condition, hyperandrogenism, is a defining characteristic of PCOS and is responsible for clinical signs like hirsutism (unwanted hair growth), acne, and sometimes hair loss from the scalp.

The body’s intricate hormonal feedback loops are disrupted. This cascade of events also interferes with the delicate hormonal choreography required for the maturation and release of an egg each month, leading to the ovulatory dysfunction and irregular cycles that define the condition.

Furthermore, hyperinsulinemia sends a signal to the liver to decrease its production of a crucial protein called Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG acts like a transport vehicle, binding to testosterone in the bloodstream and keeping it inactive. When SHBG levels fall, the amount of free, biologically active testosterone rises, amplifying the effects of hyperandrogenism throughout the body.

Dietary adjustments, therefore, are not about restriction for its own sake. They represent a targeted intervention designed to lower the volume of the insulin signal, thereby restoring balance to the entire endocrine system. By modifying what and how you eat, you gain a direct line of communication to the biochemical pathways that govern your metabolic and reproductive health.

How Does Diet Re-Establish Hormonal Dialogue?

The most effective dietary strategies for PCOS are those that directly target the root cause of the hormonal imbalance ∞ insulin resistance. The goal is to choose foods that prompt a gentler, more stable insulin response rather than sharp, demanding spikes.

This approach helps to quiet the constant hormonal noise of hyperinsulinemia, allowing other signals, like those that govern ovulation and androgen production, to be heard correctly again. A diet tailored to improve insulin sensitivity can lead to lower androgen levels, more regular menstrual cycles, and a reduction in metabolic complications.

It is a foundational tool for recalibrating the body’s internal communication network and alleviating the very symptoms that can feel so overwhelming. The process validates your experience by treating your symptoms as solvable biological responses, not personal failings.

Intermediate

Advancing from the foundational knowledge of insulin’s role in PCOS, the next step involves examining the specific dietary architectures that have demonstrated clinical efficacy. The scientific literature points toward several distinct, yet philosophically aligned, nutritional protocols. These strategies all converge on a central mechanism ∞ the regulation of blood glucose and the subsequent moderation of the body’s insulin response.

The choice among them depends on individual metabolic needs, sustainability, and personal health objectives. Each approach provides a different set of tools to achieve the same biological goal of enhanced insulin sensitivity.

The Power of Glycemic Control

A Low-Glycemic Index (LGI) diet is a structured eating pattern centered on carbohydrate quality. The Glycemic Index is a scale that ranks carbohydrate-containing foods by how much they raise blood glucose levels after being eaten. Foods with a high GI are rapidly digested and cause a significant, swift rise in blood sugar and insulin.

In contrast, low-GI foods are digested more slowly, resulting in a gradual, more stable increase in blood glucose. A meta-analysis of multiple randomized controlled trials found that LGI diets significantly improved insulin resistance, as measured by HOMA-IR, in women with PCOS.

These diets also demonstrated favorable effects on cholesterol levels, triglycerides, and total testosterone, underscoring their comprehensive metabolic benefits. This dietary pattern does not necessitate the elimination of carbohydrates, but rather a conscious selection of sources that support metabolic stability.

- Principle of LGI Eating ∞ Prioritize carbohydrates that are rich in fiber and minimally processed.

- Key Food Sources ∞ These include non-starchy vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds.

- Clinical Impact ∞ Studies show that adherence to an LGI diet can improve not only biochemical markers but also clinical outcomes like emotional health and fertility in women with PCOS.

Ketogenic Approaches a Metabolic Reset

A ketogenic diet (KD) represents a more profound metabolic intervention. By drastically reducing carbohydrate intake (typically to under 50 grams per day) and increasing fat consumption, the body shifts its primary fuel source from glucose to ketones, which are produced from the breakdown of fat.

This metabolic state, known as ketosis, results in exceptionally low and stable insulin levels. For women with PCOS, this can be a powerful tool for breaking the cycle of hyperinsulinemia. A pilot study involving overweight women with PCOS who followed a ketogenic diet for 24 weeks observed significant reductions in body weight (-12%), percent free testosterone (-22%), and fasting insulin (-54%).

Two women in the small study also became pregnant despite prior infertility issues, highlighting the diet’s potential impact on reproductive function. The pronounced effect on insulin levels directly addresses the primary driver of ovarian androgen production.

Dietary protocols for PCOS are united by their ability to moderate the body’s insulin secretion and improve cellular sensitivity.

The DASH Diet an Effective Strategy

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet is another evidence-based protocol that has shown significant benefits for women with PCOS. Originally designed to lower blood pressure, the DASH diet emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and low-fat dairy, while limiting foods high in saturated fat and sugar.

Its principles naturally create a nutrient-dense, high-fiber eating pattern that is moderately low in glycemic load. A 2024 network meta-analysis, which compared multiple dietary interventions, ranked the DASH diet as the most effective for reducing HOMA-IR, fasting blood glucose, and fasting insulin levels in women with PCOS. This suggests that its balanced, whole-foods approach is exceptionally well-suited to improving insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health in this population.

The effectiveness of these varied dietary strategies underscores a critical point. There is no single “PCOS diet,” but rather a set of guiding principles. The most successful approach will be one that an individual can adhere to consistently over the long term, as studies show that the duration of the dietary intervention is associated with the degree of improvement.

Comparing Dietary Frameworks for PCOS

| Dietary Protocol | Primary Mechanism | Typical Macronutrient Profile | Key Food Inclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Glycemic Index (LGI) | Minimizes post-meal glucose and insulin spikes by slowing carbohydrate absorption. | Moderate Carbohydrate, Moderate Protein, Variable Fat. | Legumes, non-starchy vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds. |

| Ketogenic (KD) | Induces a metabolic shift to fat-burning (ketosis), leading to very low and stable insulin levels. | Very Low Carbohydrate, Moderate Protein, High Fat. | Avocados, olive oil, nuts, seeds, fatty fish, non-starchy vegetables. |

| DASH Diet | Reduces overall metabolic load through a nutrient-dense, high-fiber, whole-foods pattern. | High Carbohydrate (from whole sources), Moderate Protein, Low-to-Moderate Fat. | Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean poultry, fish, nuts. |

Implementation Steps for a PCOS-Friendly Diet

Regardless of the specific diet chosen, certain foundational practices are universally beneficial for managing insulin resistance in PCOS.

- Prioritize Whole Foods ∞ Build your meals around unprocessed foods like vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats. These foods are naturally more satiating and have a gentler effect on blood sugar.

- Incorporate Fiber ∞ Soluble and insoluble fiber, found in vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, slows digestion and helps stabilize blood glucose levels.

- Ensure Adequate Protein ∞ Including a source of protein with each meal can increase satiety and help mitigate the glycemic response of carbohydrates.

- Choose Healthy Fats ∞ Monounsaturated and omega-3 fatty acids, found in avocados, olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish, can help reduce inflammation, which is often elevated in PCOS.

These dietary frameworks provide a clinical roadmap. They offer structured, evidence-based methods to fundamentally alter the hormonal environment that drives PCOS, moving beyond symptom management to address the underlying metabolic dysfunction.

| Clinical Outcome | Low-Glycemic Index (LGI) Diet | Ketogenic Diet (KD) | DASH Diet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) | Significant Improvement | Significant Improvement | Ranked Most Effective |

| Weight Management | Effective, especially for fat mass reduction | Highly Effective | Effective, especially when calorie-controlled |

| Androgen Levels | Reduces Total Testosterone | Reduces Free Testosterone | Reduces Androgens |

| Lipid Profile | Improves Total Cholesterol, LDL, and Triglycerides | Variable, may improve Triglycerides | Improves Triglycerides |

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of dietary efficacy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome requires an examination of the molecular and cellular underpinnings of the disorder. The clinical manifestations of PCOS are downstream consequences of a complex, tissue-specific dysregulation in insulin signaling. The phenomenon of insulin resistance in PCOS is unique.

There is a divergence in post-receptor signaling pathways, where the metabolic actions of insulin are impaired, while its mitogenic and steroidogenic actions persist, or are even amplified. This selective insulin resistance is the central node from which the syndrome’s reproductive and metabolic pathologies radiate. Dietary interventions are effective precisely because they modulate the upstream signal ∞ hyperinsulinemia ∞ that perpetuates this dysfunctional signaling cascade.

The Cellular Basis of Insulin Resistance in PCOS

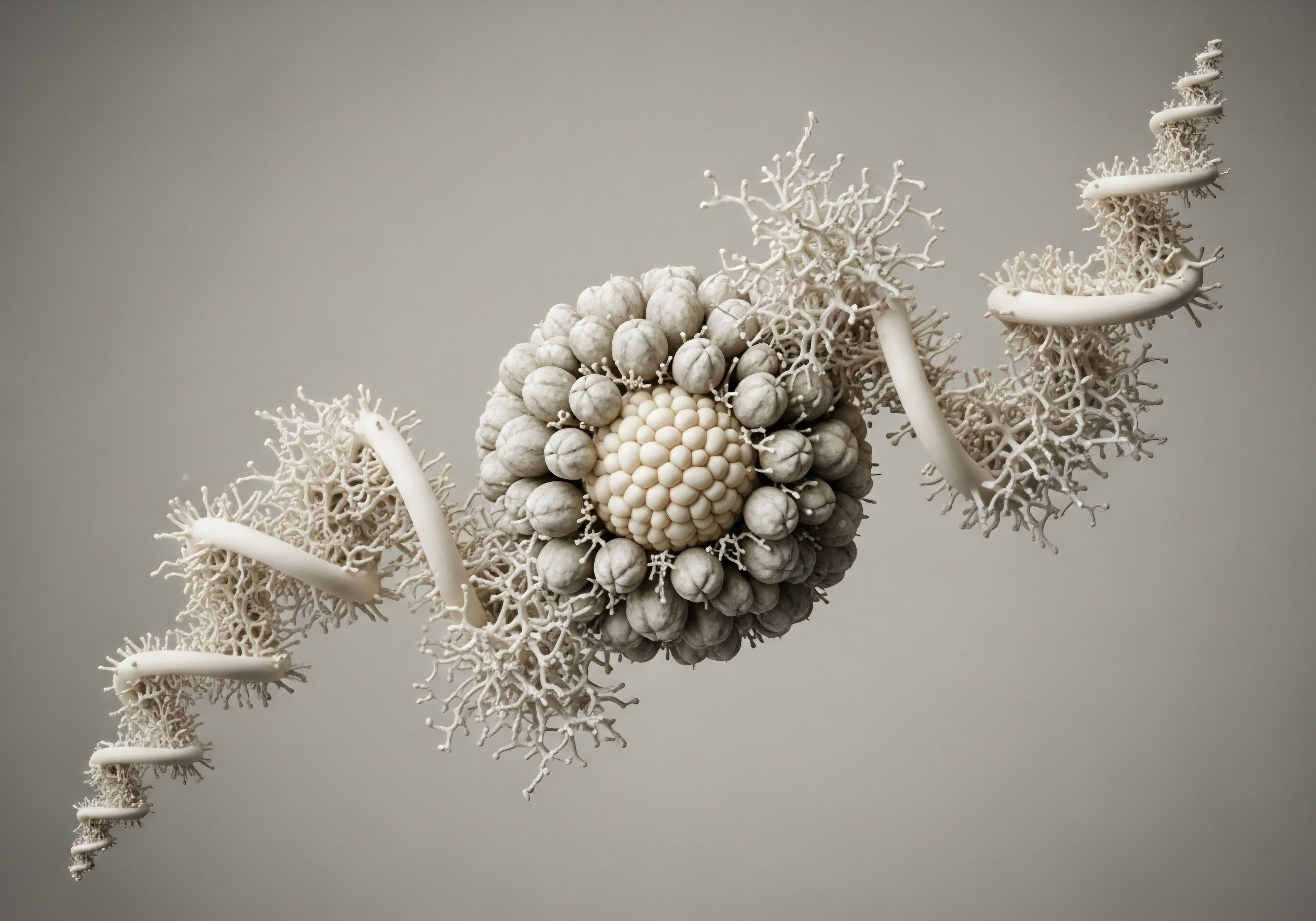

In metabolically active tissues like skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, insulin binding to its receptor normally triggers a phosphorylation cascade that activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. This pathway is critical for stimulating the translocation of the glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) to the cell membrane, facilitating glucose uptake from the blood.

In women with PCOS, there are intrinsic and extrinsic defects in this pathway, leading to impaired glucose disposal and systemic insulin resistance. However, in the theca cells of the ovary, insulin signaling through a separate pathway, the MAPK/ERK pathway, which influences cell growth and steroidogenesis, remains intact.

Chronically high insulin levels therefore continuously stimulate this pathway, leading to excessive androgen biosynthesis. This creates a paradoxical situation where the body’s tissues are resistant to insulin’s metabolic benefits, while the ovaries remain hyper-responsive to its androgen-promoting effects.

Dietary strategies succeed by reducing the chronic hyperinsulinemic state that drives the ovary’s overproduction of androgens.

The Inositol Connection and the Ovarian Paradox

The mechanism of this selective insulin resistance can be further elucidated by examining the role of inositols, specifically myo-inositol (MI) and D-chiro-inositol (DCI). These two molecules function as crucial second messengers in the insulin signaling cascade.

MI is a precursor to inositol phosphoglycans (IPGs) that mediate GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake, while DCI is involved in activating enzymes for glycogen storage. In a healthy individual, the body maintains a specific physiological ratio of MI to DCI in different tissues. This balance is disrupted in PCOS due to an enzyme called epimerase, which converts MI into DCI. The activity of this epimerase is insulin-dependent.

How Does the Ovarian Environment Become Dysregulated?

In the ovaries of women with PCOS, the constant state of hyperinsulinemia leads to over-activity of the epimerase enzyme. This causes an accelerated conversion of MI to DCI within the ovarian tissue. The result is a local deficiency of MI and an excess of DCI. This imbalance has two critical consequences:

- MI Deficiency ∞ Myo-inositol is essential for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) signaling, which is necessary for proper follicle development and oocyte maturation. A local deficiency of MI impairs the ovary’s response to FSH, contributing to anovulation and poor oocyte quality.

- DCI Excess ∞ D-chiro-inositol, when present in high concentrations in the ovary, appears to potentiate insulin’s effect on theca cells, stimulating androgen production. The excess DCI contributes directly to ovarian hyperandrogenism.

This situation is termed the “ovarian paradox.” While the rest of the body’s tissues (like muscle and fat) may be deficient in DCI-related mediators, contributing to systemic insulin resistance, the ovary suffers from a functional MI deficiency and a DCI excess.

How Do Dietary Adjustments Correct This Paradox?

Dietary strategies such as LGI, ketogenic, and DASH diets are effective because they fundamentally reduce the primary driver of this pathological process ∞ hyperinsulinemia. By lowering circulating insulin levels, these diets decrease the stimulus for epimerase over-activity within the ovary. This helps to normalize the local MI to DCI ratio, achieving two therapeutic goals simultaneously:

- Restoring FSH Sensitivity ∞ By allowing MI levels in the ovary to replete, the follicles can respond more appropriately to FSH, improving the chances of successful ovulation and enhancing oocyte quality.

- Reducing Androgen Production ∞ By decreasing the excessive local concentration of DCI, the stimulus for insulin-mediated androgen synthesis in theca cells is reduced.

This mechanistic understanding clarifies why dietary change is a cornerstone of PCOS management. It directly targets the biochemical lesion at the heart of the ovarian dysfunction. Furthermore, it explains the rationale behind the therapeutic use of inositol supplementation.

Clinical trials have shown that administering a combination of MI and DCI, typically in a 40:1 ratio that mimics the physiological plasma ratio, can help correct both the systemic insulin resistance and the local ovarian paradox. This approach improves insulin sensitivity systemically while providing the ovary with the necessary MI to restore normal function. The dietary and supplemental strategies are two sides of the same coin, both aiming to re-establish a healthy intracellular signaling environment.

References

- Shang, Y. et al. “Effect of Diet on Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 105, no. 10, 2020, pp. 3346-3360.

- Zhang, X. et al. “Dietary Modification for Reproductive Health in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 12, 2021, article 688507.

- Sivanola, M. et al. “The Role of Lifestyle Interventions in PCOS Management ∞ A Systematic Review.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 12, 2023, article 2796.

- Li, C. et al. “Ranking the dietary interventions by their effectiveness in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and network meta-analysis.” Nutrition Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, 2024, article 15.

- Paoli, A. et al. “The Ketogenic Diet in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Review of the Evidence.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 27, no. 5, 2020, pp. 300-306.

- Mavrommati, E. et al. “Effects of Dietary Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load on Cardiometabolic and Reproductive Profiles in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 151, no. 3, 2021, pp. 643-653.

- Unfer, V. et al. “The inositols and polycystic ovary syndrome.” Journal of the Turkish-German Gynecological Association, vol. 17, no. 2, 2016, pp. 111-115.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. and Papavassiliou, A. G. “Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome.” Trends in Molecular Medicine, vol. 12, no. 7, 2006, pp. 324-332.

- Laganà, A. S. et al. “Myo-inositol for insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome and gestational diabetes.” Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, vol. 14, no. 4, 2018, pp. 345-355.

- Corbould, A. “Insulin and hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.” Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, vol. 116, no. 3, 2008, pp. 144-152.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological systems at play within Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. It details the pathways, the signals, and the ways in which carefully considered dietary inputs can change the conversation your body is having with itself. This knowledge moves the locus of control, placing a powerful tool for change directly in your hands. The data and the mechanisms are the science, but your lived experience is the starting point for its application.

As you consider this information, the valuable question becomes one of personal translation. Which of these evidence-based frameworks aligns with your life, your preferences, and your unique metabolic signature? Consider your body’s signals not as frustrations, but as feedback. A path toward wellness is built by listening to that feedback and responding with informed, consistent action.

The goal is to find a sustainable way of eating that feels like a form of self-respect, a daily practice of recalibrating your system toward balance and vitality. This knowledge is the first step; the journey of applying it is a profoundly personal one.