Fundamentals

You arrive here carrying a profound and valid concern. The data you generate through wellness apps and devices ∞ your heart rate, your sleep patterns, your cycle, your stress levels ∞ feels deeply personal. It is a digital reflection of your most intimate biological rhythms.

The question of what happens when this data is shared with unknown third parties is therefore a question about your own bodily autonomy and privacy. Your apprehension is a sign of astute awareness in a digital ecosystem that was not built with your best interests at its core.

My purpose is to translate the complex, often opaque world of digital health data into clear, actionable knowledge, empowering you to understand the systems at play and reclaim a sense of control over your own biological information.

The journey begins with understanding a fundamental distinction in how health information is treated. The information you share with your physician or a hospital is designated as Protected Health Information (PHI) and is governed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

This regulation creates a fortress around your clinical data, strictly limiting how it can be used or shared. Conversely, the data collected by most consumer wellness apps and wearable devices exists in a regulatory wilderness. It is classified as consumer health data, and it falls outside of HIPAA’s protective reach.

This creates a two-tiered system of privacy, where the digital breadcrumbs of your daily health habits receive far less protection than the formal records within a clinical setting. Companies that create these wellness tools are often free to set their own policies for how your information is collected, used, and, most importantly, sold.

Your daily wellness data, unlike your clinical records, often lacks the stringent legal protection you would expect.

This absence of regulation gives rise to a business model where your personal data is the primary commodity. Many companies offering these digital tools generate revenue by aggregating the data from millions of users and selling it to other entities.

These buyers include data brokers, which are companies that specialize in creating detailed profiles of individuals by purchasing information from myriad sources. They also include advertisers who wish to target you with specific products based on your health metrics, and potentially, other corporations interested in population-level health trends. The information you provide, often in good faith to monitor your own progress, becomes a product to be packaged, analyzed, and monetized in ways you never explicitly approved.

The Commercialization of Your Biology

When you track your sleep, you are not just logging hours; you are providing a window into your stress levels, your recovery, and your overall well-being. When you log your meals, you are offering insights into your metabolic health. This information, in aggregate, is incredibly valuable.

It allows third parties to make powerful inferences about your life. An algorithm might deduce from your sleep and activity data that you are experiencing a period of high stress, leading to targeted ads for supplements or meditation apps.

It might infer from location data and workout frequency that you are committed to a healthy lifestyle, or conversely, that you may be at risk for certain conditions. This is the mechanism of digital profiling, where your biological data is used to construct a predictive model of your behavior, preferences, and future health needs. This model is then used to influence your actions and purchasing decisions, a subtle yet powerful form of manipulation driven by your own data.

What Are the Immediate Consequences?

The most immediate and tangible danger is the loss of privacy through data breaches. Digital health companies, like any tech company, are targets for hackers. A breach could expose not just your name and email, but a detailed log of your physiological state, your location history, and sensitive information about your health concerns.

For instance, data from a period-tracking app could reveal a pregnancy, a miscarriage, or attempts to conceive. In certain contexts, this information could have legal or social ramifications. Beyond the acute risk of a breach, there is the chronic risk of systemic data sharing.

Your data, once sold to a broker, can be resold and combined with other data sets ∞ your purchasing history, your public records, your social media activity ∞ to create a startlingly complete picture of your life. This erosion of privacy is a slow, often invisible process, yet it represents a significant loss of control over your personal narrative.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the dangers of sharing wellness data, we must move beyond the surface-level concern of data breaches and into the intricate architecture of the data economy. The core issue resides in how this information is processed, interpreted, and ultimately weaponized for commercial and institutional purposes.

Your lived experience of health ∞ the fatigue, the hormonal shifts, the desire for peak performance ∞ is translated into cold, hard data points. These data points then fuel sophisticated analytical systems that create a digital proxy of you, a version that can be analyzed and acted upon without your consent. This section will dissect the specific mechanisms of this process, from the illusion of “anonymized” data to the real-world consequences of algorithmic profiling.

A common reassurance provided by app developers is that user data is “anonymized” before being shared or sold. This term suggests that all personally identifiable information, such as your name and email address, has been stripped away, leaving only a set of disembodied health metrics.

The technical reality of re-identification, however, renders this promise fragile. Researchers have repeatedly demonstrated that so-called anonymized datasets can be cross-referenced with other publicly available information to re-identify individuals.

For example, a dataset containing your location data from a fitness app, even without your name, could be linked to publicly accessible social media check-ins or other geo-tagged information to reveal your identity. The unique cadence of your daily routine ∞ your commute to work, your visit to a specific clinic, your weekend habits ∞ can be as identifying as a fingerprint. This technical vulnerability means that the very concept of anonymous health data is often a fallacy.

The process of re-identifying “anonymous” data is a well-documented technical risk, challenging the privacy promises of many wellness platforms.

The Specter of Algorithmic Discrimination

Once your data is collected and linked to your identity, either directly or through re-identification, it can be used to make critical, life-altering decisions about you. This is the domain of algorithmic discrimination, where automated systems use your health data to assess your risk and value to an organization. The most significant threats lie in the realms of insurance and finance.

How Could My Insurance Premiums Be Affected?

Life and disability insurance companies operate on the principle of risk assessment. Historically, this assessment was based on your medical records and a physical exam. The vast datasets from wellness apps offer a far more granular, continuous stream of information.

An insurer could potentially purchase data from a broker that reveals your sedentary lifestyle, your poor sleep patterns, or even your grocery purchases. This information could be used to classify you as a higher risk, leading to increased premiums or an outright denial of coverage. While regulations like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) offer some protections, the data from wellness apps often occupies a legal gray area, leaving consumers vulnerable to this new form of data-driven underwriting.

The table below illustrates the stark contrast between the data traditionally used for insurance underwriting and the new forms of data becoming available through wellness apps, highlighting the expanded scope of surveillance.

| Data Source Category | Traditional Underwriting Data | Modern Wellness Data |

|---|---|---|

| Activity Level | Self-reported exercise habits, occupation | Daily step counts, GPS-tracked runs, gym check-ins, sedentary time |

| Metabolic Health | Clinical blood tests (glucose, cholesterol) | Logged meals, heart rate variability, sleep quality, stress level monitoring |

| Behavioral Patterns | Motor vehicle records, credit history | Location history, social media sentiment, online purchase history, sleep/wake times |

| Health Status | Physician reports, prescription history | Symptom tracking, cycle monitoring, self-reported mood, biometric sensor data |

The Architecture of Data Monetization

Understanding the flow of your data is key to understanding the danger. The process typically follows a predictable path, designed to extract maximum value from your information.

- Data Collection ∞ You use an app or wearable. The device collects a wide range of data, often more than is necessary for the app’s function. This includes your health metrics, location, and sometimes even your in-app behavior.

- Data Aggregation ∞ The app developer aggregates your data with that of millions of other users. At this stage, the data may undergo a superficial process of “anonymization.”

- Data Sale ∞ The aggregated dataset is sold to third parties. The primary buyers are data brokers, who specialize in enriching and reselling this information.

- Data Enrichment and Profiling ∞ The data broker combines the wellness data with other datasets they have purchased or acquired. This is where your “anonymous” health data is often re-identified and linked to your real-world identity, creating a comprehensive profile.

- Targeted Action ∞ This enriched profile is then sold to other businesses. An insurance company might use it for risk assessment, a political campaign for targeted messaging, or a consumer brand for hyper-specific advertising. Your own biology is thus used to categorize and influence you.

Academic

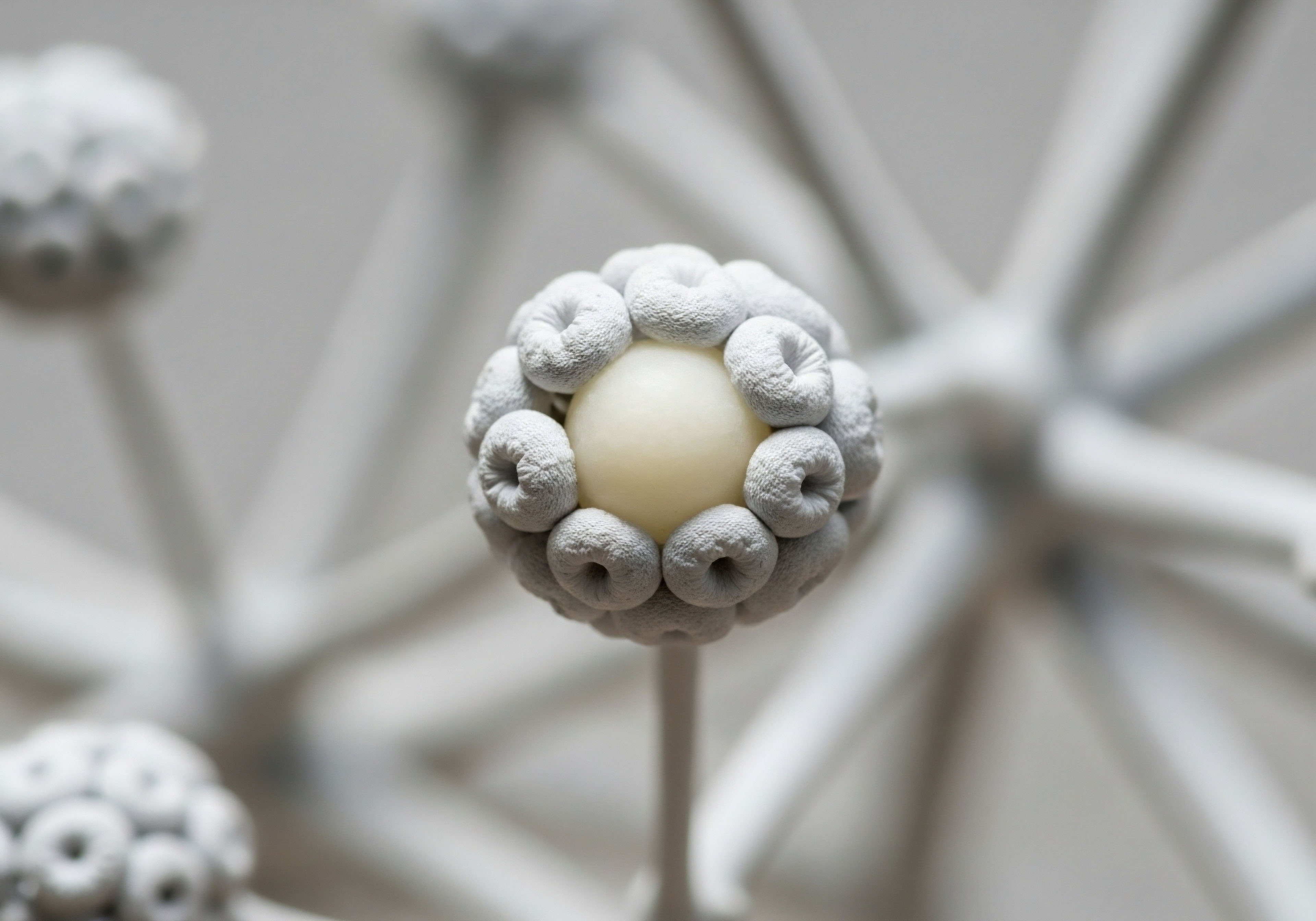

A rigorous examination of the dangers inherent in sharing wellness data requires a systems-level perspective, one that integrates the principles of endocrinology, metabolic science, and data security. The data points collected by a wearable device are not merely numbers; they are digital biomarkers that reflect the intricate operations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, the state of your metabolic function, and the subtle interplay of neurotransmitters.

When this high-fidelity biological information is exfiltrated into poorly regulated commercial ecosystems, the risks transcend simple privacy violations. They become matters of biological misinterpretation, algorithmic bias, and the potential for profound, systemic discrimination. This analysis delves into the specific vulnerabilities of high-dimensional health data and the inadequacy of current technological safeguards.

The modern wellness ecosystem operates on the extraction of what can be termed “behavioral surplus.” This concept describes the practice of collecting data far beyond what is required to deliver the user-facing service. A heart rate monitor needs to know your heart rate to function, but the platform behind it may also collect second-by-second telemetry, location data, and patterns of use.

This surplus data is the raw material for building predictive models of user behavior. A systematic review of health data privacy reveals that a majority of mobile health applications collect and transmit more data than is functionally necessary, often to a complex network of third-party trackers and data brokers. The privacy policies governing this collection are consistently found to be opaque and confusing, making true informed consent a practical impossibility for the average user.

The Unique Peril of Genomic and Endocrine Data

While all health data is sensitive, information related to our genetic makeup and endocrine function presents a unique set of dangers. The increasing popularity of direct-to-consumer genetic testing services, which often integrate with wellness platforms, means that users are sharing their immutable genetic blueprint with commercial entities.

This data, which reveals predispositions to a vast range of conditions, from metabolic disorders to neurodegenerative diseases, is a prime target for data miners. Unlike behavioral data, which can change over time, your genomic data is a permanent record.

Similarly, data that reflects endocrine function ∞ such as cycle tracking, sleep quality, and heart rate variability (a proxy for autonomic nervous system tone) ∞ provides a deep window into your physiological state. For a woman, this data can map out her entire menstrual cycle, indicating perimenopausal transitions or fertility windows.

For a man, declining sleep quality and heart rate variability could be correlated with a decline in testosterone. When fed into an algorithm, these patterns can be used to make highly specific, and potentially stigmatizing, inferences about an individual’s hormonal health, vitality, and even their suitability for certain roles or responsibilities.

The danger lies in the reduction of a complex, dynamic biological system to a set of predictive data points, which are then interpreted by a crude algorithmic lens devoid of clinical context or human empathy.

The translation of dynamic biological systems into static data points for algorithmic analysis is a primary source of risk.

De-Anonymization and the Failure of Current Privacy Models

The predominant privacy-preserving model used by commercial entities is data anonymization, followed by the sale of aggregated datasets. As established in the academic literature, this model is fundamentally flawed. High-dimensional data, which includes the rich, longitudinal data streams from wearables, is particularly susceptible to re-identification.

A study in Nature Communications demonstrated that 99.98% of Americans could be correctly re-identified in any dataset using just 15 demographic attributes. The combination of age, gender, zip code, and a few health data points can be enough to pinpoint an individual with alarming accuracy.

The table below outlines some of the advanced privacy-preserving technologies discussed in the academic literature and their current limitations in the context of consumer wellness data.

| Technology | Mechanism | Limitations in Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Homomorphic Encryption | Allows for computation on encrypted data without decrypting it first. | Computationally intensive and expensive, making it impractical for the high-volume, real-time data processing required by most wellness apps. |

| Federated Learning | Trains machine learning models locally on user devices, sharing only the model updates, not the raw data. | Requires significant computational power on the user’s device and can still be vulnerable to inference attacks that reconstruct user data from the model updates. |

| Differential Privacy | Adds statistical “noise” to a dataset to protect individual identities while allowing for aggregate analysis. | A trade-off exists between privacy and accuracy. The level of noise required to truly protect individuals can render the data useless for granular analysis. |

| Blockchain | Creates a decentralized, immutable ledger for data transactions, potentially giving users more control. | Scalability issues, high energy consumption, and the public nature of most blockchains can create new privacy vulnerabilities if not implemented correctly. |

The core issue is that these advanced techniques are rarely implemented in the consumer wellness space due to cost, complexity, and a business model that disincentivizes robust privacy. The economic incentive lies in the unfettered collection and sale of data, not in its protection. Therefore, the data representing your most intimate biological processes is secured by the weakest, most easily defeated methods, creating a systemic risk that affects anyone participating in this digital ecosystem.

References

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism ∞ The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs, 2019.

- Al-Rubaie, M. & J. M. Chang. “Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning ∞ A Systematic Literature Review.” IEEE Access, vol. 8, 2020, pp. 123695-123715.

- Sun, G. et al. “Security and Privacy of Technologies in Health Information Systems ∞ A Systematic Literature Review.” MDPI Electronics, vol. 11, no. 9, 2022, p. 1345.

- Rocher, L. J. M. Hendrickx, & Y-A. de Montjoye. “Estimating the success of re-identifications in incomplete datasets using generative models.” Nature Communications, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, p. 3069.

- O’Loughlin, K. et al. “Privacy Practices of Health Information Technologies ∞ Privacy Policy Risk Assessment Study and Proposed Guidelines.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 23, no. 9, 2021, e29204.

- World Privacy Forum. “The Scoring of America ∞ How Secret Consumer Scores Threaten Your Privacy and Your Future.” 2014.

- Abouelmehdi, K. A. Beni-Hssane, & H. Khaloufi. “Big data security and privacy in healthcare ∞ A systematic review.” Journal of Big Data, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018, p. 1.

- Ghasemi, M. Z. Zare, & M. R. Meybodi. “A systematic literature review on privacy risks in health big data.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.03811, 2025.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Compass

You have now journeyed through the intricate landscape of digital health data, from the clear and present dangers of commercial exploitation to the deep, systemic risks embedded in the very architecture of our modern data economy. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose.

It acts as a calibration tool for your internal compass, allowing you to navigate this world with a newfound clarity and a heightened sense of your own biological sovereignty. The feelings of unease you may have started with are now contextualized, validated by a clear understanding of the mechanisms at play.

This understanding is the first, essential step. The path forward involves a series of personal calculations, a conscious weighing of convenience against vulnerability. It prompts a dialogue with yourself about the true value of the data you generate and the level of trust you are willing to place in the digital custodians of that information.

Each decision to use a device, to enable a permission, to agree to a policy, becomes an informed choice rather than a passive acceptance. Your health journey is uniquely your own; the way you manage its digital footprint should be as well. The power resides in this deliberate, conscious engagement with the tools you choose to bring into your life.