Fundamentals

Your body is a finely tuned system of communication. Every sensation, every action, every moment of healing is coordinated by a constant flow of molecular messages. When you feel a surge of energy, a pang of hunger, or the calm of recovery, you are experiencing the direct result of this internal dialogue.

The language of this dialogue is written in molecules, principally in chains of amino acids. Understanding the vocabulary of this language is the first step toward comprehending your own biology on a more intimate level. We begin not with complex definitions, but with a simple, foundational principle ∞ the size and complexity of the message determines its function and its name.

At the heart of this system are amino acids, the elemental building blocks of both peptides and proteins. Think of them as the alphabet. When these letters are strung together by chemical links called peptide bonds, they form words and sentences. A short, simple chain of these amino acids is called a peptide.

These are the body’s equivalent of a concise, direct command or a quick status update. They are designed for rapid, specific tasks, delivering their message and then quickly degrading. Their small size allows for this efficiency, a molecular signal meant to act in the here and now.

The Spectrum of Molecular Messengers

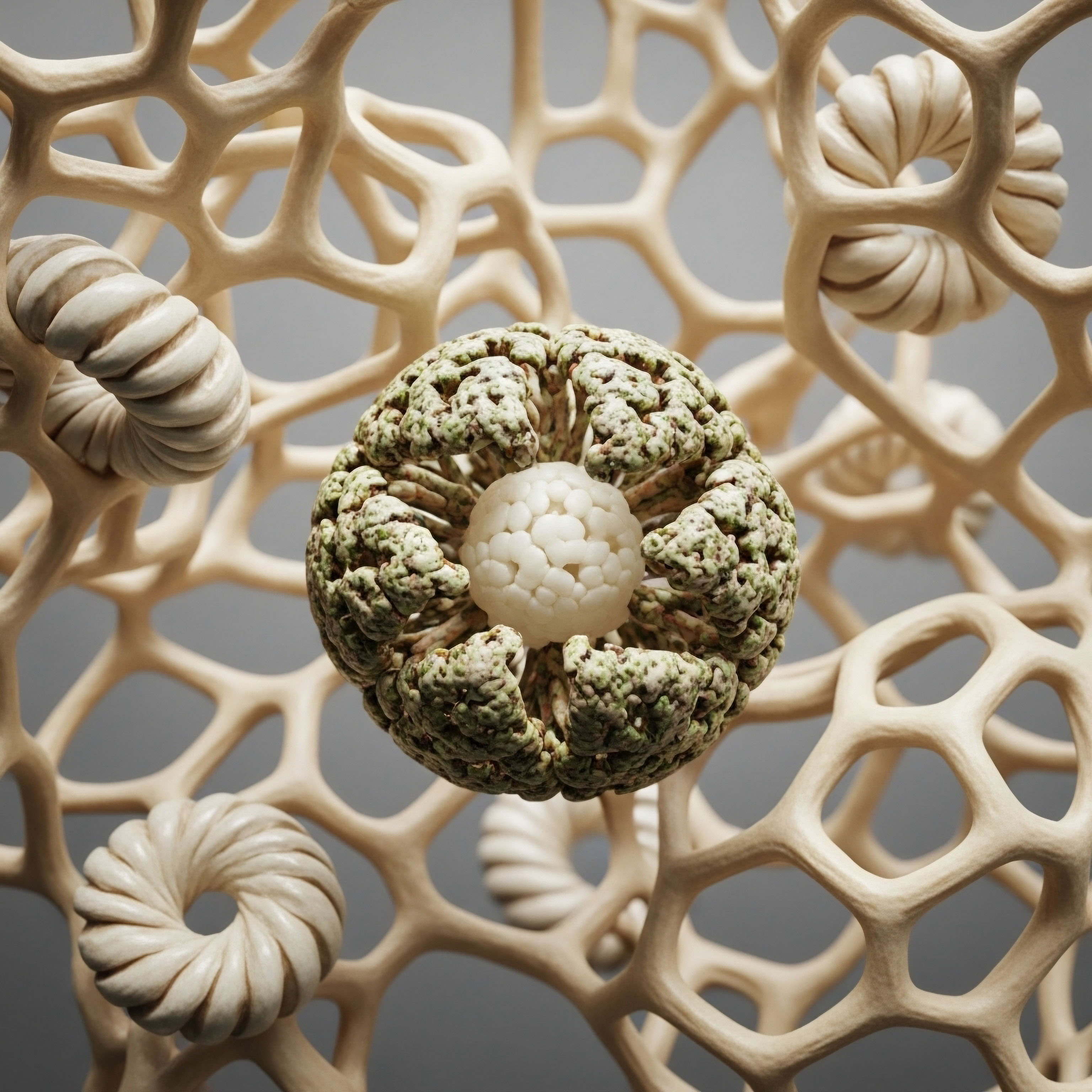

As these chains of amino acids grow longer and more elaborate, they begin to fold into complex, three-dimensional shapes. This transition from a simple chain to a complex structure marks the point where a peptide becomes a protein. A protein is a masterpiece of biological engineering.

Its intricate architecture is directly tied to its function, allowing it to act as an enzyme, a structural component, or a sophisticated long-term signaling molecule. It is the body’s equivalent of a detailed blueprint or a comprehensive instruction manual, capable of carrying out complex and sustained operations.

To bring clarity to this spectrum, regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have established a practical, working distinction. An amino acid polymer with a specific, defined sequence of 40 amino acids or fewer is classified as a peptide. Conversely, a polymer chain exceeding 40 amino acids is defined as a protein.

This numerical dividing line provides a clear and consistent standard for scientists, clinicians, and drug manufacturers. It is a foundational criterion that helps determine how these therapeutic molecules are developed, regulated, and ultimately used to support human health.

A molecule’s classification as a peptide or protein begins with a simple count of its amino acid building blocks.

This distinction based on size is the starting point for a much deeper conversation. It influences how a therapeutic agent is constructed, how it behaves within your body, and the clinical pathway it follows before it can be prescribed.

The journey of a molecule from the laboratory to your physician’s office is shaped by whether it is a concise peptide or a complex protein. This initial classification has profound implications for the development of therapies that aim to restore balance and function to your body’s intricate communication network.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational concept of size, the criteria that separate a peptide drug from a protein biologic become a matter of structure, origin, and regulation. These factors are interconnected, each influencing the others and collectively defining the therapeutic’s identity.

Understanding these distinctions is essential for appreciating how a specific therapy is designed to interact with your unique physiology and the meticulous process that ensures its safety and efficacy. The classification is a clinical and legal framework built upon the inherent molecular properties of these agents.

What Are the Core Distinguishing Factors?

Four primary criteria create the functional separation between peptide drugs and protein biologics. Each element provides a different lens through which to view these powerful therapeutic tools, moving from the molecule’s physical nature to its journey through the regulatory system. These are the pillars upon which the clinical and pharmaceutical worlds build their understanding and application of these therapies.

- Amino Acid Count and Molecular Weight ∞ This is the initial “bright-line” test. Peptide drugs consist of 40 or fewer amino acids, resulting in a low molecular weight. This smaller size often allows for more straightforward chemical synthesis. Protein biologics, with more than 40 amino acids, can extend to thousands of residues, leading to high molecular weights that necessitate production in living systems.

- Structural Complexity ∞ Peptides typically exhibit simpler primary and secondary structures, often existing as linear chains or simple helices. Proteins, however, possess intricate tertiary (three-dimensional folding) and sometimes quaternary (multiple subunits) structures. This complex architecture is vital for a protein’s specific biological function and is also what makes them sensitive to manufacturing and handling conditions.

- Method of Production ∞ The manufacturing process represents a fundamental divergence. Peptide drugs are generally created through controlled, predictable chemical synthesis in a laboratory. Protein biologics are produced using recombinant DNA technology, where genetic material is inserted into living cells (like bacteria, yeast, or mammalian cells) that then manufacture the protein. This biological process introduces variability that must be rigorously controlled.

- Regulatory Pathway ∞ In the United States, these production differences lead to two distinct regulatory approvals. Peptide drugs, as synthesized molecules, are typically approved via a New Drug Application (NDA). Protein biologics, products of living systems, require a Biologic License Application (BLA). This separation governs everything from clinical trial design to the approval of subsequent generic or biosimilar versions.

A Comparative Analysis of Therapeutic Classes

The practical implications of these criteria are significant for both the clinician and the patient. The choice between a peptide and a protein therapy is informed by these deep-seated differences, which affect how the treatment is administered, how the body responds, and its accessibility.

| Criterion | Peptide Drug | Protein Biologic |

|---|---|---|

| Size (Amino Acids) | 40 or fewer | Greater than 40 |

| Structure | Simple; linear or simple helix (primary/secondary) | Complex; 3D folding (tertiary/quaternary) |

| Production Method | Chemical Synthesis | Recombinant DNA in Living Cells |

| Primary Regulatory Body (U.S.) | Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) | Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) |

| Regulatory Application | New Drug Application (NDA) | Biologic License Application (BLA) |

| Follow-On Product | Generic | Biosimilar |

The path a therapeutic molecule takes from laboratory to patient is fundamentally determined by its size, structure, and source.

For instance, the complexity and cellular origin of a protein biologic mean that creating a “copy” is far more challenging than for a chemically synthesized peptide. A follow-on version of a biologic is called a biosimilar, reflecting that it is highly similar, but not identical, to the original.

A generic peptide, however, can be an exact replica of the original synthesized molecule. This distinction has direct consequences on the cost and availability of these treatments long after the original patent has expired. The framework is designed to account for the inherent complexity of working with molecules derived from living systems.

Academic

The distinctions between a protein biologic and a peptide drug, while codified by regulatory bright lines, manifest most profoundly at the interface of pharmacology and immunology. The physical and manufacturing dissimilarities give rise to divergent behaviors within the human body, influencing everything from metabolic fate to the potential for an immune response.

An academic exploration of these criteria reveals a landscape of clinical nuance where molecular characteristics dictate therapeutic strategy and patient outcomes. It is in this domain that we appreciate the full weight of the classification.

How Does Molecular Origin Shape Immunogenicity?

One of the most significant clinical consequences of the protein versus peptide distinction is the concept of immunogenicity ∞ the propensity of a therapeutic agent to provoke an unwanted immune response. The immune system is exquisitely tuned to identify and neutralize foreign biological matter. Protein biologics, by their very nature, carry a higher intrinsic risk of being recognized as foreign. This stems from two core attributes.

First, their large size and complex, folded structures present a multitude of potential epitopes, which are specific sites on the molecule that can be recognized by immune cells. A larger, more complex surface area provides more opportunities for the immune system to “see” the therapeutic as non-self.

Second, their production in non-human cell lines (such as Chinese Hamster Ovary cells) can introduce subtle post-translational modifications, like glycosylation patterns, that differ from those found in humans. These subtle variations can be flagged by the immune system, leading to the development of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs).

The formation of ADAs can neutralize the therapeutic, reducing its efficacy, or in some cases, trigger serious adverse events. This potential for an immune reaction necessitates rigorous monitoring and characterization during the development of any biologic.

Peptide drugs, due to their smaller size and chemical synthesis, generally exhibit lower immunogenicity. Their simple structures present fewer epitopes, and chemical synthesis ensures a homogenous product free of potentially immunogenic cellular contaminants or non-human modifications. This gives them a pharmacological advantage in certain contexts, as they are less likely to be inactivated by the patient’s own immune system over time.

Pharmacokinetics the Impact of Size and Structure

The behavior of a drug in the body over time, its pharmacokinetics, is also deeply influenced by these defining criteria. The processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) are starkly different for a small peptide versus a large protein.

- Absorption and Administration ∞ Large proteins are almost always administered via injection (subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous) because their size and complexity prevent them from surviving the harsh environment of the digestive tract and passing through the intestinal wall. Many smaller peptides face the same fate, though ongoing research into oral delivery systems is a dynamic field.

- Distribution ∞ Once in circulation, a protein’s large size often restricts its distribution to the vascular and interstitial spaces. Peptides, being smaller, may penetrate tissues more readily, although this is highly dependent on the specific molecule’s chemical properties.

- Metabolism and Half-Life ∞ This is a critical point of divergence. Small peptides are often rapidly cleared from circulation by proteolytic enzymes and renal filtration, resulting in a very short half-life, sometimes mere minutes. This necessitates frequent dosing or formulation in extended-release depots. Large proteins are cleared more slowly, their size protecting them from rapid renal clearance and enzymatic degradation, leading to a much longer half-life that allows for less frequent dosing intervals. For example, monoclonal antibodies, a class of protein biologics, can have half-lives measured in weeks.

When Does a Peptide Behave like a Protein?

The regulatory line at 40 amino acids is a bright one, yet pharmaceutical science continually engineers molecules that operate in the gray area. Advanced peptide chemistry now allows for the synthesis of molecules approaching 100 amino acids, blurring the manufacturing distinction. Furthermore, chemical modifications are used to bestow protein-like properties upon peptides.

A prominent example is PEGylation, the process of attaching polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to a peptide. This modification increases the molecule’s hydrodynamic size, effectively shielding it from renal clearance and enzymatic degradation. The result is a peptide drug with a dramatically extended half-life, behaving pharmacokinetically much more like a protein biologic. These hybrid molecules challenge simple classification and demonstrate that the functional properties of a drug can be deliberately engineered.

A molecule’s clinical behavior is a direct consequence of its physical structure and manufacturing origin.

This deep dive reveals that the criteria separating these two classes of drugs are far from arbitrary. They are rooted in fundamental principles of biology, chemistry, and medicine. The classification of a therapeutic as a protein biologic or a peptide drug is a clinical shorthand for a whole suite of expected behaviors, risks, and therapeutic strategies. It informs the physician’s approach to treatment and provides a framework for developing ever more sophisticated and targeted therapies.

| Characteristic | Peptide Drug | Protein Biologic |

|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity Risk | Generally low; fewer epitopes, synthetic purity. | Higher; large size, complex structure, potential for non-human modifications. |

| Typical Half-Life | Short (minutes to hours); rapid enzymatic and renal clearance. | Long (days to weeks); slower clearance due to large size. |

| Primary Clearance Route | Renal filtration and enzymatic degradation. | Proteolytic degradation and target-mediated clearance. |

| Delivery Route | Primarily injectable; some nasal or transdermal routes explored. | Injectable (subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous). |

References

- Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati. “FDA Releases Final Guidance ∞ Transition of Previously Approved Drugs to Being ‘Deemed Licensed’ Biologics.” JD Supra, 6 Mar. 2020.

- Food and Drug Administration. “Definition of the Term ‘Biological Product’; Proposed Rule.” Federal Register, vol. 83, no. 239, 12 Dec. 2018, pp. 63893-63901.

- Broussard, Suzanne. “What Are the Major Regulatory Differences for Getting a Biologic Product Versus a Drug Compound into The Marketplace? BLA vs NDA.” Criterion Edge, 2020.

- Food and Drug Administration. “Definition of the Term ‘Biological Product’; Final Rule.” Federal Register, vol. 85, no. 35, 21 Feb. 2020, pp. 10057-10064.

- GaBI Online. “FDA issues new rule on definition of term ‘biological product’.” Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal), 6 Mar. 2020.

Reflection

You began this exploration with the lived experience of your own body’s internal communication. The knowledge you have gathered here ∞ distinguishing the concise message of a peptide from the detailed manual of a protein ∞ transforms abstract science into a tangible understanding of therapeutic design.

This is the essential purpose of clinical translation ∞ to equip you with the clarity to see the logic behind the medicine. This understanding is the foundation. The next step is to consider how these precisely defined tools might apply to your own unique biological system, a personal inquiry best guided by a partnership with a qualified clinical expert who can translate this knowledge into a personalized protocol.