Fundamentals

A Personal Question of Hormonal Balance

You may be reading this because you have started, or are considering, a hormonal optimization protocol that includes androgen therapy. It is a path many women take seeking to reclaim vitality, sharpen cognitive function, or restore a sense of well-being that has felt distant.

Amid the anticipated benefits, a deeply personal and important question often arises ∞ how does this affect my uterine health? This question comes from a place of profound self-awareness and a desire to ensure that in optimizing one aspect of your biology, you are carefully stewarding the whole.

Your concern is valid, and it points to a sophisticated understanding of the body as an interconnected system. The conversation about androgen therapy in women is evolving, and your question is at the very forefront of personalized, proactive wellness.

The endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, is a remarkably dynamic tissue. Its behavior is governed by a finely tuned dialogue between hormones. For much of your life, this dialogue has been dominated by the cyclical rise and fall of estrogen and progesterone.

Estrogen, particularly estradiol, instructs the endometrium to grow and thicken each month, preparing a potential home for a fertilized egg. Progesterone then arrives after ovulation, shifting the endometrium’s function from proliferation to stabilization and maturation. If pregnancy does not occur, progesterone levels fall, signaling the lining to shed. This cycle is a foundational rhythm of female biology.

Understanding the endometrium’s response to hormonal signals is the first step in ensuring its health during any hormonal therapy.

When we introduce androgen therapy, we are adding a new voice to this hormonal conversation. The primary androgen used in female protocols is testosterone. While often associated with male physiology, testosterone is a vital hormone for women, contributing to libido, bone density, muscle mass, and mood.

The core of ensuring endometrial safety during androgen therapy lies in understanding how testosterone and its metabolites interact with this sensitive tissue. The body can convert testosterone into other hormones. Through a process called aromatization, testosterone can be transformed into estradiol.

This means that introducing testosterone could potentially increase estrogen levels, which in turn could stimulate the endometrial lining to grow. Unopposed estrogenic stimulation, without the balancing effect of progesterone, is a primary risk factor for the development of endometrial hyperplasia, a condition of excessive cell growth that can sometimes lead to cancer. Therefore, monitoring endometrial health is a critical component of a responsible and effective hormonal optimization strategy.

The Protective Role of Progesterone

The key to maintaining a healthy endometrium during any hormonal therapy that might increase estrogenic stimulation is the presence of progesterone. Progesterone is the great counterbalance to estrogen’s proliferative signal. It acts as a maturational signal, telling the endometrial cells to stop dividing and to differentiate into a stable, secretory lining.

This is why, in conventional hormone replacement therapy for postmenopausal women with a uterus, progesterone (or a synthetic progestin) is always co-prescribed with estrogen. It provides the “off” switch to estrogen’s “on” switch.

In the context of androgen therapy for women, this principle remains the same. If a woman has a uterus, the potential for testosterone to convert to estradiol must be respected and managed. The primary strategy for this is ensuring adequate progesterone exposure.

For a pre- or perimenopausal woman who is still ovulating and producing her own progesterone, her natural cycle may provide sufficient protection. For a postmenopausal woman, or a woman on a protocol that suppresses her natural cycle, the co-administration of progesterone is a standard and essential part of the safety protocol. This is a foundational concept ∞ estrogen builds the lining, and progesterone protects it. Any therapeutic intervention that influences one side of this equation must account for the other.

Initial Assessment and Foundational Biomarkers

So, how do we begin to assess endometrial health? The process starts with a baseline evaluation and continues with regular monitoring. The initial biomarkers are not complex blood tests but are instead functional and anatomical assessments that give us a clear picture of the endometrium’s status.

- Symptom Monitoring ∞ The most basic, yet essential, biomarker is the absence of unscheduled uterine bleeding. Any bleeding or spotting that occurs outside of an expected menstrual cycle (in pre- or perimenopausal women) or any bleeding at all (in postmenopausal women) requires immediate evaluation. This is a direct signal from the body that the endometrial lining may be unstable or overly stimulated.

- Transvaginal Ultrasound ∞ This imaging technique is a cornerstone of endometrial assessment. It uses sound waves to create a clear picture of the uterus and allows a clinician to precisely measure the thickness of the endometrial lining, referred to as the endometrial stripe. A thin, well-defined stripe is reassuring, while a thickened or irregular stripe would prompt further investigation.

- Progesterone Challenge Test ∞ For women who are not having regular cycles, this test can be very informative. It involves taking a course of progesterone for 10-14 days. If the woman experiences a withdrawal bleed after stopping the progesterone, it indicates that her body had produced enough estrogen to build up the uterine lining. This confirms that the endometrium is responsive and that an estrogenic environment exists, reinforcing the need for ongoing progesterone opposition.

These initial steps provide the foundational data points. They establish a baseline and create the framework for ongoing monitoring. They translate the complex internal hormonal milieu into clear, actionable information, allowing you and your clinician to proceed with confidence, knowing that a robust safety plan is in place.

Intermediate

Interpreting the Endometrial Ultrasound

The transvaginal ultrasound is the primary surveillance tool for endometrial health in women undergoing androgen therapy. Its value lies in its ability to provide a direct, non-invasive visualization of the uterine lining. The key measurement obtained is the endometrial thickness. The interpretation of this measurement, however, depends entirely on the individual’s menopausal status and hormonal context.

For a postmenopausal woman not on any hormone therapy, a very thin endometrial stripe is expected, typically less than 4-5 millimeters (mm). This thinness reflects the low-estrogen environment. When a postmenopausal woman is on androgen therapy, this 5 mm threshold remains a critical safety benchmark.

An endometrial thickness measurement that remains consistently below 5 mm is a strong indicator of endometrial atrophy (a normal, thin state) and provides a high degree of confidence that there is no excessive stimulation occurring. Studies on women using testosterone have shown that it does not independently stimulate endometrial proliferation; in fact, some evidence suggests it may have an antiproliferative effect.

The concern, as previously discussed, is its conversion to estradiol. Therefore, a thin endometrial stripe on ultrasound suggests that this conversion is not leading to clinically significant estrogenic effects on the uterus, or that any such effects are being adequately opposed by progesterone.

What If the Endometrial Lining Is Thickened?

An endometrial thickness measurement exceeding 5 mm in a postmenopausal woman, or one that shows significant interval growth in any woman on androgen therapy, is a biomarker that requires a structured response. It is not an immediate diagnosis of a problem, but a signal to gather more information.

The first step is often to rule out benign causes, such as small endometrial polyps or fibroids, which can also increase the measured thickness. If no benign cause is apparent, the next step is to obtain a tissue sample for histologic analysis. This is the definitive way to assess the health of the endometrial cells themselves.

The two primary methods for obtaining a tissue sample are:

- Endometrial Biopsy ∞ A common in-office procedure where a thin, flexible tube is passed through the cervix to suction a small sample of the endometrial lining. It is quick and provides a direct assessment of the tissue’s architecture.

- Hysteroscopy with Dilation and Curettage (D&C) ∞ A more comprehensive procedure, often done in a surgical setting. A thin, lighted camera (hysteroscope) is inserted into the uterus to visually inspect the entire lining. This allows for targeted biopsies of any suspicious areas and is often combined with a D&C to remove a larger sample of tissue for analysis.

The pathology report from this tissue sample is the ultimate biomarker. It will classify the endometrium as benign (e.g. proliferative, secretory, or atrophic), or it will identify the presence of hyperplasia (with or without atypia) or, in rare cases, carcinoma. This information dictates all subsequent clinical decisions.

Systemic Hormonal Biomarkers and Their Significance

While direct assessment of the endometrium is paramount, monitoring systemic hormone levels provides crucial context. Blood tests for key hormones help to understand the overall endocrine environment that the endometrium is being exposed to. These tests are not direct markers of endometrial health, but they are essential for managing the therapy that influences it.

Systemic hormone levels offer a window into the biochemical environment, allowing for precise adjustments to the therapeutic protocol.

The following table outlines the key hormonal biomarkers to monitor in a woman on androgen therapy and the rationale for each.

| Biomarker | Clinical Rationale and Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Total and Free Testosterone |

This is the primary measure of therapeutic dosing. The goal is to bring testosterone levels into the optimal physiological range for a healthy young woman, typically the upper quartile of the normal reference range. Levels that are excessively high increase the substrate available for aromatization into estradiol, potentially increasing the risk of endometrial stimulation. |

| Estradiol (E2) |

This is a critical safety marker. Monitoring estradiol levels directly assesses the degree of testosterone aromatization. While on therapy, estradiol levels should be monitored to ensure they do not rise to a level that would confer risk. In postmenopausal women, these levels should remain low. If estradiol levels are elevated, it may indicate a need to adjust the testosterone dose or, in some cases, consider the use of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole, though this is less common in female protocols than in male TRT. |

| Progesterone |

For women taking supplemental progesterone, measuring levels can confirm absorption and adequacy of dosing, although this is not always necessary as the protective effect is the primary goal. For premenopausal women not on supplemental progesterone, a mid-luteal phase progesterone level can confirm ovulation and adequate endogenous production, which is protective for the endometrium. |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) |

SHBG is a protein that binds to sex hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, rendering them inactive. Testosterone therapy can lower SHBG levels. A lower SHBG means that a higher fraction of the total testosterone is “free” and biologically active. Monitoring SHBG helps to correctly interpret the free testosterone and free estradiol levels, giving a more accurate picture of the hormones available to act on tissues like the endometrium. |

The Integrated Monitoring Protocol

Optimal management combines these anatomical and biochemical biomarkers into a cohesive protocol. This creates a system of checks and balances to ensure both efficacy and safety. A typical monitoring schedule for a woman on androgen therapy with an intact uterus would look something like this:

- Baseline Assessment ∞ Before initiating therapy, a baseline transvaginal ultrasound and a full hormonal panel (Testosterone, Estradiol, Progesterone, SHBG) are established. Any pre-existing endometrial abnormalities are addressed.

- Initial Follow-up (3-6 months) ∞ Hormone levels are re-checked to ensure the testosterone dose is appropriate and to assess the impact on estradiol levels. The patient is questioned about any unscheduled bleeding.

- Annual Surveillance ∞ A transvaginal ultrasound is performed annually to monitor endometrial thickness. Hormone levels are also checked annually or more frequently if doses are adjusted.

- As-Needed Evaluation ∞ Any instance of unscheduled bleeding or spotting must trigger an immediate evaluation, typically starting with a transvaginal ultrasound and proceeding to endometrial sampling if the lining is thickened.

This structured approach allows for the personalization of therapy. It recognizes that each woman’s body will respond uniquely to hormonal inputs. By systematically monitoring these key biomarkers, it is possible to tailor the protocol ∞ adjusting testosterone dosage, ensuring adequate progesterone opposition ∞ to maintain the endometrium in a safe, quiescent state while achieving the systemic benefits of the therapy.

Academic

Molecular Mechanisms of Androgen Action in the Endometrium

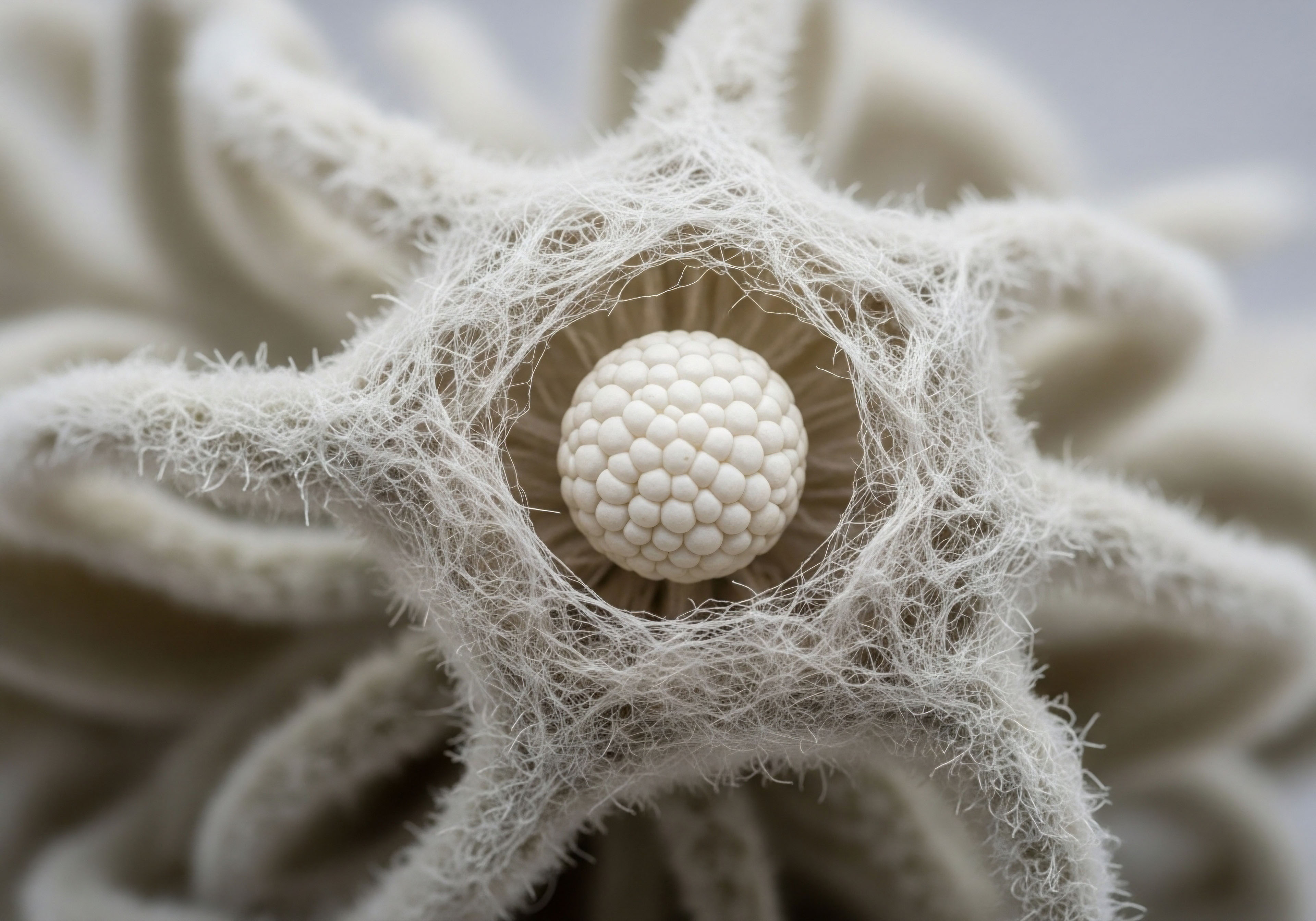

A sophisticated understanding of endometrial health during androgen therapy requires moving beyond macroscopic measurements and into the molecular landscape of the endometrial cell itself. The endometrium is not merely a passive recipient of hormonal signals; it is an active participant, expressing a complex array of hormone receptors and local metabolic enzymes that determine its response.

The primary mechanism of androgen action is through the androgen receptor (AR), a nuclear transcription factor that, when activated by testosterone or its more potent metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT), can directly modulate gene expression.

Research has demonstrated that AR is expressed in both the stromal and glandular components of the human endometrium. Its expression appears to be cycle-dependent, suggesting a physiological role. The direct effects of AR activation in endometrial tissue appear to be primarily anti-proliferative and pro-differentiative.

In vitro studies have shown that androgens can inhibit estrogen-induced growth of endometrial cells and can promote stromal cell decidualization, a process of maturation that is critical for implantation and endometrial stability. This suggests a direct, protective role for androgens, which may help to explain why testosterone therapy, when properly managed, does not typically induce endometrial hyperplasia.

The clinical data from studies on transmasculine individuals on high-dose testosterone therapy further supports this, showing a significant tendency towards endometrial atrophy, not proliferation.

However, the net effect of androgen therapy on the endometrium is a summation of multiple, sometimes opposing, molecular pathways. The two most important are:

- Direct AR-Mediated Effects ∞ As described, these are generally anti-proliferative and contribute to endometrial stability.

- Indirect Estrogenic Effects ∞ This occurs via the local conversion of testosterone to estradiol by the enzyme aromatase, which is present in endometrial tissue as well as adipose tissue. This locally produced estradiol can then bind to estrogen receptors (ER-alpha and ER-beta) and exert a classic proliferative stimulus.

The ultimate response of the endometrium depends on the balance between these direct androgenic and indirect estrogenic signals, as well as the all-important presence of progesterone acting through its own progesterone receptors (PR-A and PR-B). A healthy, protected endometrium is one in which the anti-proliferative signals from progesterone and direct androgen action outweigh the proliferative signals from systemic and locally produced estrogen.

Advanced Biomarkers from Endometrial Histology

When an endometrial biopsy is performed, standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining provides the crucial diagnosis of hyperplasia or malignancy. However, the tissue sample can be subjected to more advanced molecular analysis to yield a far deeper understanding of the endometrial environment. These techniques, while not yet standard for routine monitoring, are invaluable in complex cases and in research settings, and they point to the future of personalized endometrial assessment.

Histological analysis can be extended with molecular tools to quantify the precise hormonal signaling status within the endometrial tissue.

This table details some of these advanced immunohistochemical (IHC) markers and their significance.

| Molecular Marker (IHC) | Biological Function and Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Ki-67 |

Ki-67 is a protein that is present in the nucleus of cells during all active phases of the cell cycle (G1, S, G2, M) but is absent in resting cells (G0). Its presence is a direct and quantifiable measure of cellular proliferation. A low Ki-67 index in an endometrial biopsy is a powerful molecular confirmation of a quiescent, non-proliferating endometrium, providing a high degree of reassurance. Conversely, a high Ki-67 index indicates significant proliferative activity, even in the absence of frank hyperplasia, and would signal a need to increase progesterone opposition or decrease the estrogenic load. |

| Estrogen Receptor (ER) & Progesterone Receptor (PR) |

Staining for ER and PR quantifies the expression of the very receptors that mediate hormonal effects. A healthy, progesterone-dominant endometrium should show strong PR expression, as progesterone upregulates its own receptor. Conversely, unopposed estrogen stimulation can downregulate both ER and PR, a paradoxical finding seen in some forms of endometrial hyperplasia. Assessing the ratio and distribution of these receptors provides a functional snapshot of the tissue’s hormonal status and its potential responsiveness to therapy. |

| PTEN (Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog) |

PTEN is a critical tumor suppressor gene. Loss of PTEN function is one of the earliest and most common molecular events in the development of endometrioid-type endometrial cancer. Immunohistochemical staining can detect the loss of the PTEN protein. While not a routine marker for monitoring, its absence in a biopsy is a significant finding that indicates a field defect and a heightened risk of progression to malignancy, requiring definitive management. |

| p53 |

The p53 protein is another crucial tumor suppressor, often called the “guardian of the genome.” Mutations in the TP53 gene are characteristic of the more aggressive, serous-type endometrial cancers. Abnormal p53 staining patterns (either complete absence or strong, diffuse overexpression) in a biopsy are a marker of a high-risk lesion, even if the histology is ambiguous. This finding has profound prognostic implications. |

What Is the Future of Endometrial Surveillance?

The future of assessing endometrial health will likely move toward less invasive and more functionally informative biomarkers. While ultrasound and biopsy will remain important, emerging fields offer the potential for a more nuanced understanding. One area of intense research is the analysis of the endometrial fluid aspirate.

This fluid, obtained through a simple, office-based procedure similar to an endometrial biopsy but less invasive, contains a rich soup of proteins, lipids, microRNAs, and exfoliated cells. Analyzing this “liquid biopsy” of the uterus could provide a real-time molecular snapshot of the endometrium’s health without requiring a tissue sample.

Furthermore, the concept of endometrial receptivity, primarily studied in the context of in-vitro fertilization, has relevance here. Tests like the Endometrial Receptivity Analysis (ERA), which analyze the expression of hundreds of genes related to the window of implantation, are fundamentally assessing the endometrium’s response to progesterone.

A “receptive” profile is, by definition, a progesterone-dominant, non-proliferating profile. While not designed for cancer screening, the molecular signature of a non-receptive or “pre-receptive” endometrium could, in this context, be a reassuring sign of a safe, atrophic state. The integration of these transcriptomic and proteomic approaches with traditional clinical methods represents the next frontier in ensuring the long-term safety and health of the endometrium for women on all forms of hormonal therapy.

References

- Michels, K. A. et al. “Postmenopausal Androgen Metabolism and Endometrial Cancer Risk in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 109, no. 5, 2017, djw288.

- Asseler, J. D. et al. “Endometrial thickness assessed by transvaginal ultrasound in transmasculine people taking testosterone compared with cisgender women.” Reproductive BioMedicine Online, vol. 45, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1033-1038.

- Slayden, O. D. and R. M. Brenner. “Effects of Testosterone Treatment on Endometrial Proliferation in Postmenopausal Women.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 83, no. 2, 1998, pp. 381-386.

- Simitsidellis, I. Saunders, P. T. K. & Gibson, D. A. “Androgens and endometrium ∞ New insights and new targets.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 465, 2018, pp. 48-60.

- Deligdisch, L. “Effects of hormone therapy on the endometrium.” Modern Pathology, vol. 6, no. 1, 1993, pp. 94-106.

- Wierman, M. E. et al. “Androgen Therapy in Women ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 99, no. 10, 2014, pp. 3489-3510.

- “Endometrial thickness.” Radiopaedia.org, Radiopaedia.org, 18 Sept. 2023.

- Prior, J. C. “Progesterone Is Important for Transgender Women’s Therapy ∞ Applying Evidence for the Benefits of Progesterone in Ciswomen.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 104, no. 4, 2019, pp. 1181-1186.

- Revel, A. et al. “Endometrial receptivity markers, the journey to successful embryo implantation.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 13, no. 1, 2007, pp. 83-92.

- Rechberger, T. et al. “What Role do Androgens Play in Endometrial Cancer?” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 4, 2023, p. 3943.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Biology

The information presented here provides a map of the biological terrain, outlining the known pathways and the clinical tools used to navigate them. This knowledge is a form of power. It transforms abstract concern into a structured, manageable process. Your journey with hormonal optimization is deeply personal, a continuous dialogue between how you feel and what the objective data reveals.

The biomarkers of endometrial health are simply the language of that dialogue, the tangible points of connection that allow you and your clinical guide to make informed, collaborative decisions.

Consider this knowledge not as a set of rigid rules, but as the foundational understanding needed to ask more precise questions. How does my body aromatize testosterone? What is my individual sensitivity to estrogenic stimulation? How does my system respond to progesterone? The answers to these questions will define your unique path.

The goal is to achieve a state of calibrated equilibrium, where every system is supported and vitality is reclaimed without compromise. This process is a testament to the remarkable capacity of the human body to adapt and the power of scientific insight to guide that process with wisdom and care.