Fundamentals

You have likely held the results of a wellness screening in your hands, a page filled with numbers and ranges that represent a snapshot of your internal world. It is a deeply personal document, reflecting the intricate processes that sustain you. A natural question arises from this experience ∞ what information is truly private, and what is accessible?

The answer lies in understanding the precise focus of a key piece of federal legislation, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, or GINA. This law establishes a clear boundary, safeguarding a specific type of biological information.

GINA’s protective shield is built around the concept of your genetic blueprint. It safeguards the information encoded in your DNA, the inherited instructions that you carry from birth. This includes the results of direct genetic tests, such as those that identify predispositions to certain conditions.

The law extends this protection to the genetic information of your family members and your documented family medical history, as these elements can offer predictive insights into your own potential health future. The core purpose is to prevent decisions being made about you based on a health condition you do not currently have but might one day develop.

The Boundary of Protection

The legislation’s protections are specific and targeted. GINA is fundamentally about predictive health information derived from your genes. It addresses the “what if” scenarios suggested by your DNA. This focus means that a vast category of health data falls outside its scope.

The law is designed to prevent discrimination based on your potential future health, not your current state of being. Its aim is to ensure that opportunities are not limited by the story your genes might tell about tomorrow.

GINA’s protections are centered on preventing discrimination based on potential, inherited health risks rather than current physiological status.

What, then, constitutes the information that a wellness screening can legitimately assess? The answer involves a different class of biological data. These are the markers that illustrate your body’s present condition. Think of them as readouts from your body’s operational systems. They measure metabolites, proteins, and cellular counts that reflect your current physiological function.

These are the numbers on your screening report, such as cholesterol levels, blood glucose, and liver enzyme counts. They provide a picture of your health today, a direct result of the complex interplay between your genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

Intermediate

To fully grasp the landscape of a corporate wellness screening, one must understand the distinction between two categories of biological information ∞ your genetic predispositions and your current physiological state. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) is constructed to protect the former. It treats your genetic code and family medical history as privileged information in the context of employment and health insurance, preventing these factors from being used to make predictive judgments about your future health risks.

A wellness program operating within GINA’s rules can request certain health information, provided it does so on a strictly voluntary basis. This means you must provide prior, knowing, and written consent. The program cannot penalize you for choosing not to provide genetic information.

For instance, you might be offered an incentive for completing a health risk assessment. You would still receive that incentive even if you leave the questions about family medical history blank. This structure is intended to create a clear separation between participation in a wellness program and the disclosure of sensitive genetic data.

What Is the Practical Difference in a Blood Test?

The practical application of GINA’s rules becomes clear when looking at a standard blood panel. A vial of blood contains a universe of information, but GINA cordons off a very specific portion of it. The law is concerned with tests that analyze your DNA or chromosomes to identify gene variants linked to disease.

Standard blood tests performed in a wellness screening do something else entirely. They measure the concentration of substances circulating in your blood at that moment, offering a real-time assessment of your metabolic and organ function.

This table illustrates the distinction between the protected and unprotected categories of information within a typical wellness program framework.

| Protected Genetic Information Under GINA | Permissible Biomarkers in Voluntary Screenings |

|---|---|

| Results of a BRCA1/BRCA2 gene test for cancer risk. | Complete Blood Count (CBC) including red and white blood cell counts. |

| Family history of Huntington’s disease. | Lipid Panel (Total Cholesterol, LDL, HDL, Triglycerides). |

| Genetic test showing a predisposition for Lynch syndrome. | Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP) including glucose, calcium, and electrolytes. |

| Information about a family member’s genetic carrier status. | Liver function tests (ALT, AST). |

| Request for or receipt of genetic counseling services. | Kidney function tests (BUN, Creatinine). |

| Genetic information of a fetus or embryo. | Inflammatory markers like C-Reactive Protein (CRP). |

The Concept of Manifest Disease

A critical element in GINA’s legal framework is the concept of a “manifest disease or disorder.” GINA’s protections apply to the predictive information about a condition you do not have.

Once an individual has been diagnosed with a condition and is showing symptoms, that condition is considered “manifest.” At that point, other laws, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), come into play to govern accommodations and prevent discrimination based on the disability itself. GINA’s role is to protect the unexpressed genetic potential, preserving your opportunities from being constrained by a risk that has not yet come to pass.

Standard wellness screenings assess current health indicators like cholesterol and glucose, which are distinct from the predictive genetic data protected by GINA.

This distinction is vital for understanding the flow of information. An employer cannot ask if you have a gene variant that increases your risk for type 2 diabetes. They can, however, within a voluntary wellness program, screen for your current blood glucose and HbA1c levels.

One is a predictive genetic risk; the other is a measure of your current metabolic health. This boundary allows wellness programs to function by focusing on current, modifiable health factors while preventing them from delving into your immutable genetic legacy.

Academic

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 represents a foundational piece of civil rights legislation for the genomic era. Its architecture, however, reveals a specific and deliberate focus that creates a significant gap between what is considered “genetic information” and the broader universe of biological markers.

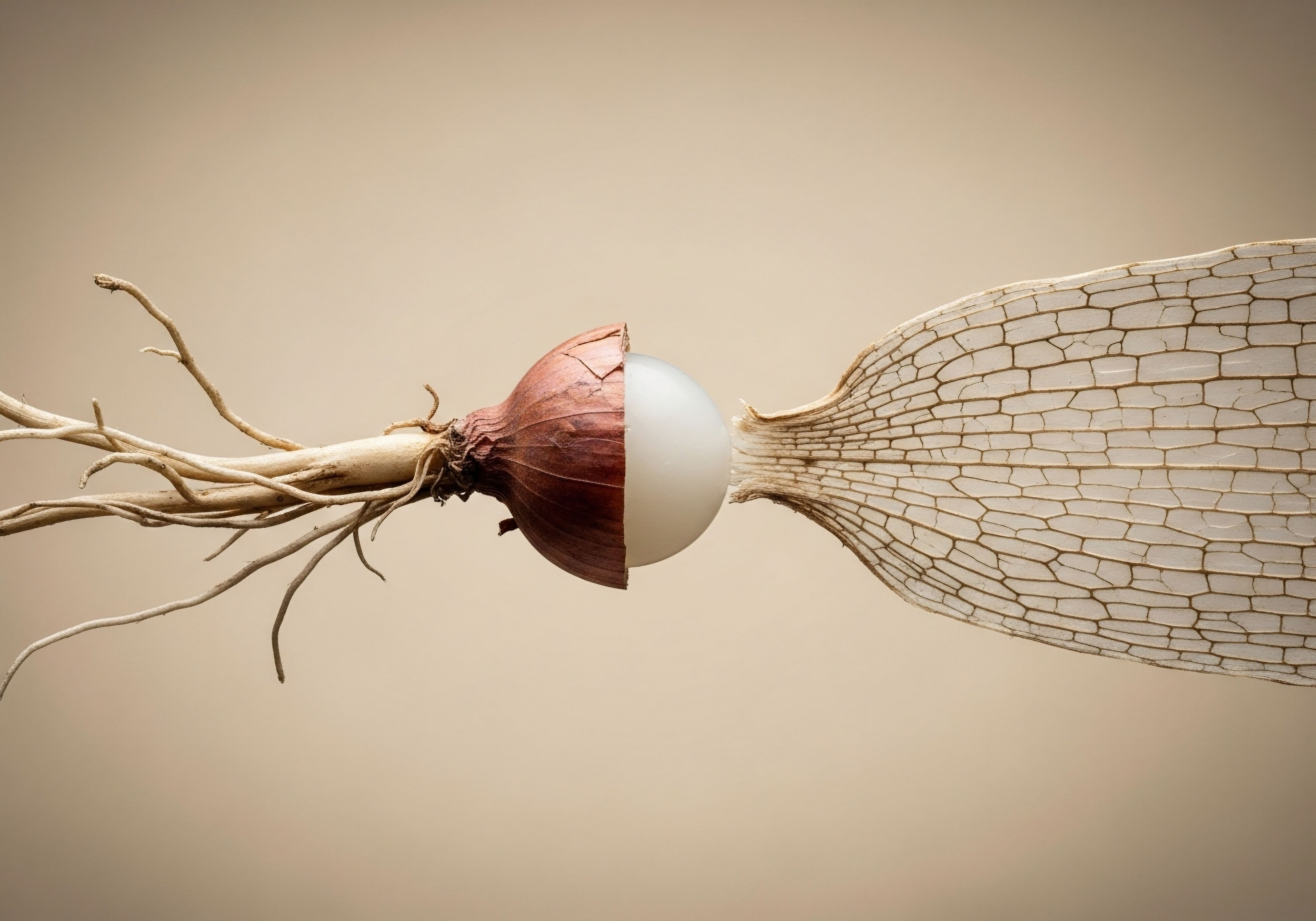

From a systems-biology perspective, the distinction is almost artificial, as all physiological processes are influenced by genetics. Legally, the distinction is paramount. GINA’s definition of genetic information is narrow, encompassing an individual’s genetic tests (analysis of DNA, RNA, chromosomes), the genetic tests of family members, and the manifestation of disease in family members.

This precise legal definition leaves a vast and growing field of non-genetic biomarkers outside its protective scope. A biomarker is a measurable indicator of some biological state or condition. While some biomarkers are explicitly genetic, many are proteins, metabolites, lipids, or inflammatory molecules whose levels reflect the dynamic interplay of genes, environment, and lifestyle. These biomarkers provide a high-resolution snapshot of an individual’s current health status, and their collection within a wellness context is largely ungoverned by GINA.

How Does the Law Classify Different Biomarkers?

The legal and clinical classification of biomarkers is essential to understanding the limits of GINA’s protections. The legislation effectively creates a hierarchy of data based on its source and predictive nature. Information derived directly from the genome is protected, while information reflecting the downstream output of physiological systems is not.

The following table provides a more detailed classification of biomarker types, clarifying their relationship to the GINA framework.

| Biomarker Class | Description | GINA Protection Status |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Biomarkers | Direct analysis of DNA/RNA sequences or chromosomal changes (e.g. single nucleotide polymorphisms, gene mutations). | Protected. This is the core definition of “genetic information.” |

| Proteomic Biomarkers | Measurement of proteins or peptides in tissues or fluids (e.g. Prostate-Specific Antigen, C-Reactive Protein). | Excluded. These reflect current physiological processes, not direct genetic code. |

| Metabolomic Biomarkers | Measurement of small molecules involved in metabolism (e.g. glucose, cholesterol, uric acid). | Excluded. These are considered indicators of current metabolic function. |

| Transcriptomic Biomarkers | Measurement of gene expression levels (RNA). | Protected. As this involves analysis of RNA, it falls under the definition of a genetic test. |

| Epigenetic Biomarkers | Analysis of modifications to DNA that do not change the sequence itself (e.g. DNA methylation). | Ambiguous/Likely Protected. This area is legally developing, but as it involves analysis of DNA, it would likely be considered a genetic test. |

The Emerging Challenge of Precision Medicine

The advancement of precision medicine and high-throughput screening technologies presents a growing challenge to the adequacy of GINA’s framework. It is now possible to generate vast amounts of proteomic and metabolomic data from a single blood sample.

This data can be used in algorithms to create highly predictive risk scores for various diseases, achieving a level of predictive power that rivals some genetic tests. Yet, because these biomarkers are not derived from direct DNA analysis, they are not covered by GINA.

The legal framework of GINA protects the genetic blueprint, while the vast landscape of protein and metabolic biomarkers that reflect current health remains outside its scope.

This creates a potential loophole. An organization could theoretically develop a comprehensive health risk profile of an individual based on a panel of unprotected biomarkers, effectively circumventing the spirit of the law. The legislation was written before the current explosion in biomarker discovery and data analytics.

Consequently, a legal and ethical debate is underway regarding whether existing protections should be expanded to cover other forms of predictive health information, ensuring that the original intent of the law keeps pace with the progress of science.

- Genomic Data ∞ The primary focus of GINA is the protection of an individual’s raw genetic sequence and inherited predispositions. This information is seen as immutable and highly predictive, warranting special legal status.

- Phenotypic Data ∞ The law permits the collection of phenotypic data, which are the observable characteristics of an individual, including the results of most standard blood tests. These biomarkers are viewed as a reflection of current health, influenced by a combination of genetics and external factors.

- Regulatory Lag ∞ There is an observable lag between the rapid advancement of biomedical technology and the evolution of legal frameworks. The increasing predictive power of non-genetic biomarkers raises questions about whether the legal definition of protected health information needs to be broadened to prevent new forms of discrimination.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008.” Title II of GINA, Pub. L. 110-233, 122 Stat. 881.

- Rothstein, Mark A. “Is GINA Obsolete?” Hastings Center Report, vol. 49, no. 5, 2019, pp. 3-4.

- Green, Robert C. et al. “GINA, Genetic Discrimination, and Genomic Medicine.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 372, no. 12, 2015, pp. 1166-1168.

- Allyse, Megan A. et al. “Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 ∞ Acknowledging the Perceived Need for Protection.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 83, no. 11, 2008, pp. 1269-1272.

- Hudson, Kathy L. “Genomics, Health Care, and Society.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 365, no. 11, 2011, pp. 1033-1041.

- Prince, Anya E. R. and Benjamin E. Berkman. “When is a Medical Test a Genetic Test? Re-evaluating the Definition of ‘Genetic Test’ in the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 45, no. 1, 2017, pp. 101-113.

- Starke, C. et al. “Genetic Testing in Natural History Studies ∞ A Review of the Regulatory and Legal Landscape.” Biomarkers in Medicine, vol. 15, no. 6, 2021, pp. 437-449.

- Javitt, Gail H. and Kathy Hudson. “The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act ∞ A new law for a new era of medicine.” The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 83, no. 4, 2008, pp. 433-436.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The knowledge of what is measured, what is protected, and what is revealed is the first step in a much longer, more personal process. Your health data tells a story, a complex narrative written in the language of proteins, metabolites, and genes.

Understanding the grammar of this language allows you to become an active participant in that story. Each biomarker, each result, is a point of information. It is a signpost, not a destination. The true value of this information is unlocked when it is used not as a label, but as a guide for proactive, informed decisions about the systems that support your vitality.