Fundamentals

You feel it in your energy, your mood, your sleep. You notice a shift in how your body responds to stress, to food, to exercise. This internal experience, this intimate knowledge of your own system, is the most valid data point you possess.

When you seek answers, you are often presented with charts and reference ranges that describe a statistical average, a composite of thousands of other people. Yet, you are not a statistical average. Your biology is uniquely yours, written in a code that dictates the very rhythm of your internal chemistry.

Understanding this code is the first step toward a new conversation about your health, one where your lived experience is explained and validated by the profound science of your own design.

At the heart of this personal biology lies the endocrine system, a magnificent communication network. Hormones are the messengers in this system, traveling through the bloodstream to deliver precise instructions to cells and organs. These instructions govern everything from your metabolic rate to your reproductive cycle.

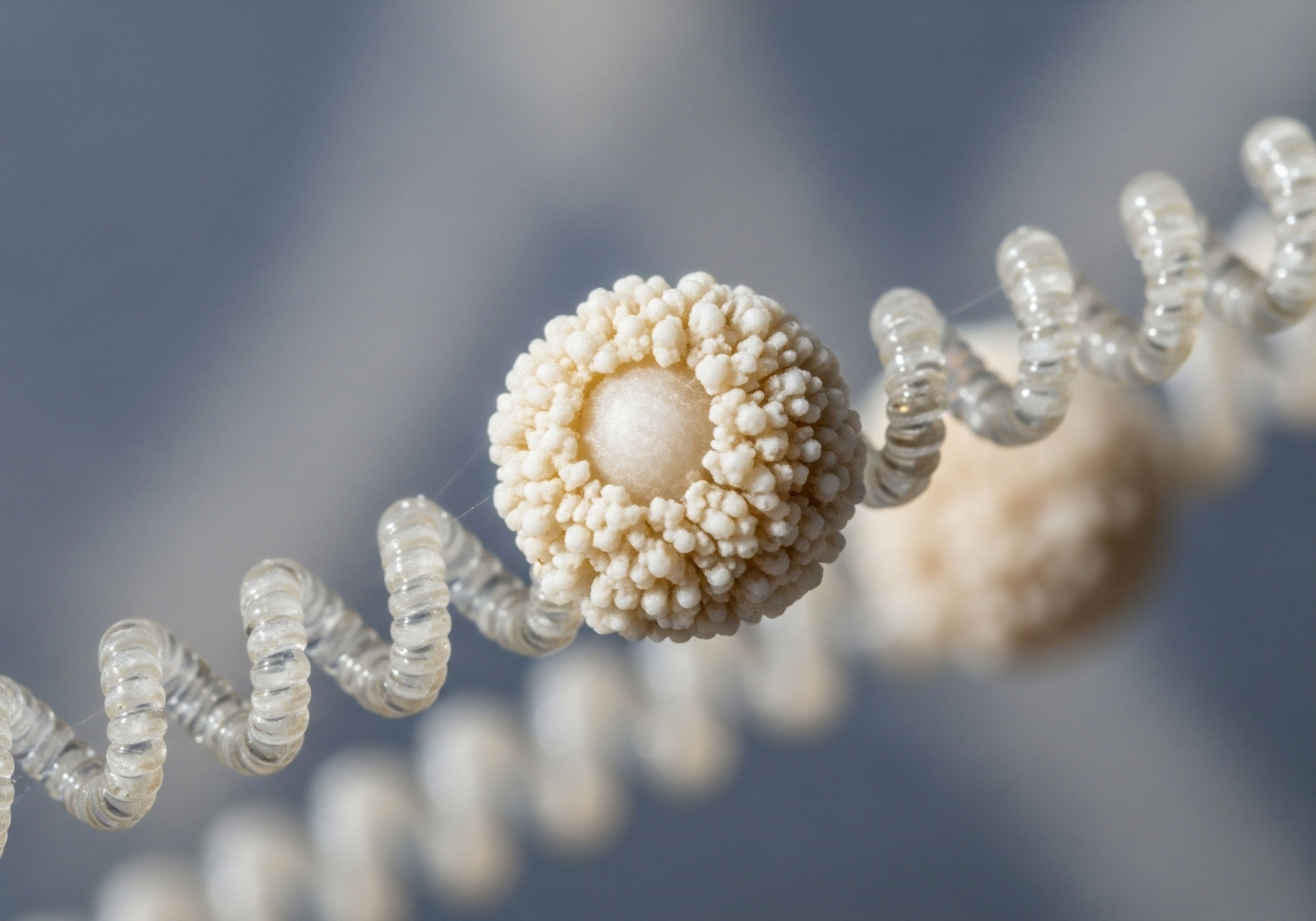

The production, transportation, and breakdown of these messengers is a process of breathtaking precision, a biochemical dance choreographed by your genetic blueprint. This blueprint, your DNA, contains the specific instructions for building the proteins, enzymes, and receptors that manage every facet of hormonal health. It is within this intricate code that we find the source of your unique hormonal signature.

The Genetic Blueprint for Hormonal Function

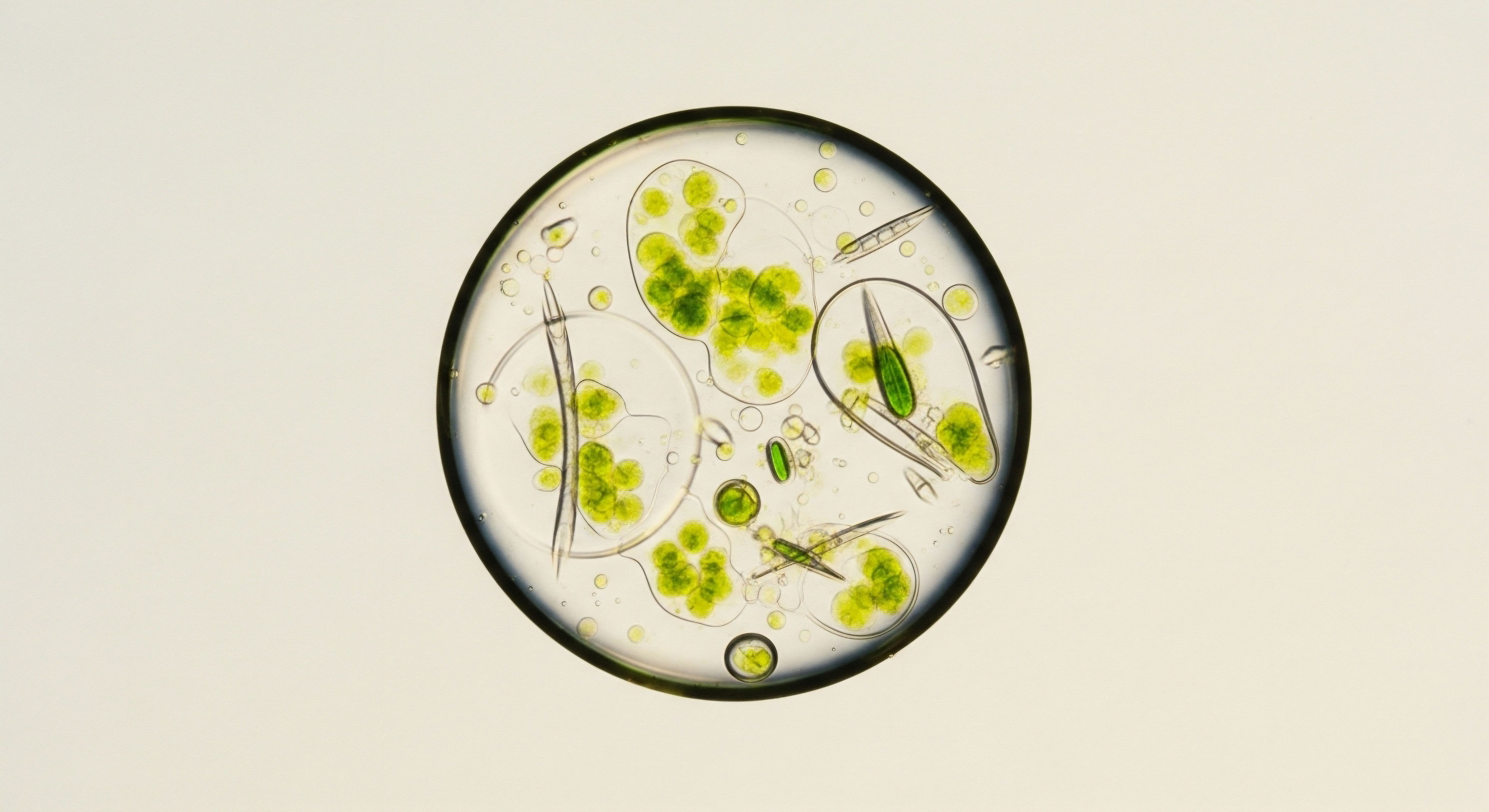

Every hormone in your body follows a lifecycle. It is synthesized from raw materials, released into circulation, binds to a receptor to deliver its message, and is eventually metabolized and cleared from the system. Each step of this journey is facilitated by enzymes, which are specialized proteins that act as catalysts for biochemical reactions.

The instructions for building each specific enzyme are encoded in a corresponding gene. A genetic variation, often called a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), is a common, normal variation in the sequence of that gene. These variations are what make each of us unique. They are subtle alterations in the blueprint’s instructions.

Imagine the process of hormone metabolism as a highly specialized assembly line. One enzyme is responsible for converting cholesterol into pregnenolone, the precursor to many other steroid hormones. Another enzyme, aromatase, is responsible for converting testosterone into estrogen. A different set of enzymes, primarily in the liver, is tasked with deactivating and packaging these hormones for removal.

A genetic variation can be likened to a subtle modification of one of the machines on this assembly line. One variation might make a particular machine run slightly faster, while another might cause it to run a bit slower. The result is a metabolic pathway that is inherently tailored to you. This explains why two individuals can follow identical lifestyle patterns yet exhibit vastly different hormonal profiles.

Your genetic code provides the fundamental instructions that orchestrate the lifelong production and processing of your body’s hormonal messengers.

This inherent biological individuality has profound implications. It means that your capacity to produce testosterone, your efficiency in converting it to estrogen, and your ability to clear used hormones from your system are all influenced by your unique genetic makeup. This foundational knowledge moves the conversation about health from a generic model to a personalized one.

It provides a biological context for why you feel the way you do and illuminates a path toward protocols that work with your body’s innate design, aiming to restore vitality and function in a way that is congruent with your own internal architecture.

Intermediate

Understanding that our genetic blueprint influences our hormonal symphony is the first step. The next is to identify the specific genetic players and understand their precise roles. In clinical practice, we move beyond the general concept and into the specifics of pharmacogenomics, the study of how genes affect a person’s response to drugs and, by extension, to hormonal therapies.

This field provides a powerful lens through which we can anticipate an individual’s biochemical tendencies, allowing for a more precise and personalized application of support protocols like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy.

The machinery of hormone metabolism is largely driven by specific families of enzymes. These are the workers on the assembly line, and their efficiency is dictated by their genetic coding. Variations in these genes can lead to clinically significant differences in how both endogenous hormones and therapeutic hormones are processed.

For anyone considering or currently undergoing hormonal optimization, understanding these key genetic variations can be the difference between a successful protocol and one that produces frustrating side effects. It is the science of anticipating the body’s response before the first intervention is ever made.

Key Genes in Steroid Hormone Metabolism

Steroid hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, are metabolized through a series of complex, multi-stage pathways. Certain genes encode the enzymes that perform the most critical steps in these pathways. Variations in these genes are common in the population and can significantly alter the speed and direction of hormone conversion and clearance. By examining these variations, we can construct a more complete picture of an individual’s endocrine predispositions.

- CYP19A1 This gene codes for the enzyme aromatase, which is responsible for the conversion of androgens (like testosterone) into estrogens. A SNP that results in increased aromatase activity can mean that a man on TRT may convert a larger portion of his therapeutic testosterone into estradiol. This can lead to side effects such as water retention and mood changes, necessitating proactive management with an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole.

- COMT (Catechol-O-Methyltransferase) This enzyme is vital for breaking down catechol estrogens, which are metabolites of estrogen. Certain variations in the COMT gene lead to slower enzyme activity. For an individual with slow COMT function, estrogen metabolites can accumulate. This has implications for both men and women, as the buildup of these metabolites can influence cellular health and overall inflammatory status.

- SHBG (Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin) While not an enzyme, the SHBG gene codes for a protein that binds to sex hormones in the bloodstream, rendering them inactive. Genetic variations can lead to higher or lower baseline levels of SHBG. A person with a genetic tendency for high SHBG may have a high total testosterone level but a low free testosterone level, as more of the hormone is bound and unavailable to the tissues. This is a critical distinction in diagnosing and managing hormonal imbalances.

How Do Genetic Profiles Influence Clinical Protocols?

The knowledge of these genetic tendencies allows for a proactive, personalized approach to hormonal therapy. Instead of starting with a standard, one-size-fits-all protocol and adjusting based on side effects, we can use genetic information to inform the initial design of the protocol. This is the essence of data-driven, personalized medicine. It is a shift from a reactive model to a predictive one, where we anticipate the body’s unique metabolic signature and tailor the therapy accordingly.

Genetic variations in key metabolic enzymes directly inform how an individual will likely respond to specific hormonal therapies.

For instance, consider two men preparing to start TRT. Man A has a common variation in the CYP19A1 gene that leads to higher aromatase activity. Man B has a typical CYP19A1 gene. A standard TRT protocol might work perfectly for Man B, but it could lead to elevated estrogen levels and associated side effects in Man A.

By knowing this information upfront, a clinician can initiate Man A’s protocol with a concurrent low dose of Anastrozole, potentially preventing the side effects before they occur. This is a more elegant and efficient approach to biochemical recalibration.

| Gene | Enzyme/Protein | Function | Impact of Common Variations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP19A1 | Aromatase | Converts testosterone to estrogen | Can increase or decrease the rate of conversion, affecting the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio. |

| COMT | Catechol-O-Methyltransferase | Breaks down estrogen metabolites | Slower versions can lead to an accumulation of metabolites, influencing cellular health. |

| SHBG | Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin | Binds and transports sex hormones | Can lead to naturally higher or lower levels of free, bioavailable hormones. |

| UGT2B17 | UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase | Metabolizes and clears testosterone | Gene deletions, common in some populations, can drastically slow testosterone clearance. |

This level of personalization extends to other therapies as well. The response to peptide therapies like Sermorelin or CJC-1295, which stimulate the body’s own growth hormone production, is also governed by the integrity of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

Genetic factors influencing this axis can inform the selection of the most effective peptide protocol for an individual’s goals, whether they are focused on anti-aging, muscle gain, or improved sleep. The future of wellness protocols lies in this synergy between understanding the person’s subjective experience and interpreting their objective genetic data.

Academic

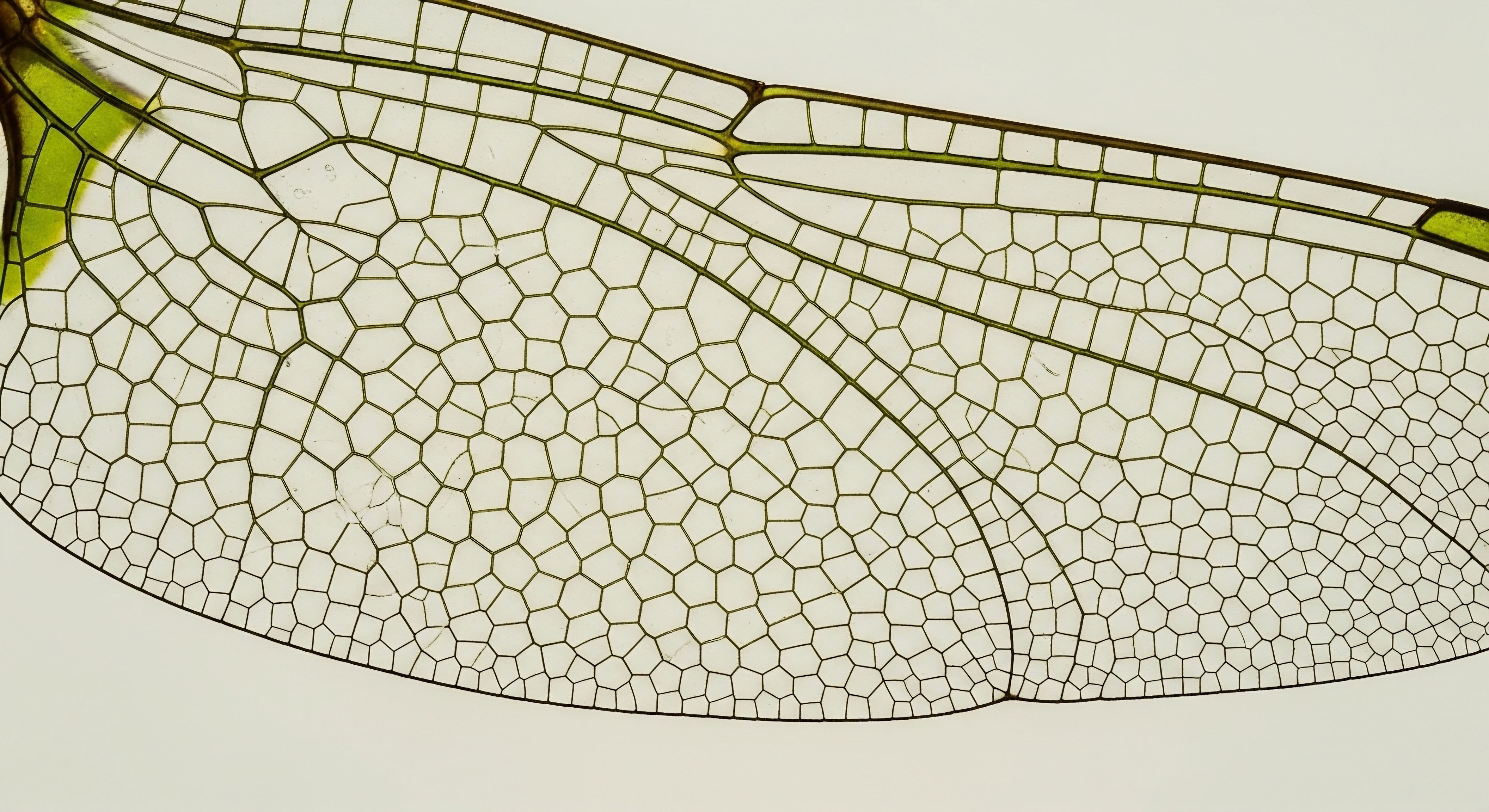

A sophisticated understanding of hormonal health requires moving beyond the measurement of circulating hormone concentrations and toward an appreciation of the complete biological circuit. This circuit includes not only hormone synthesis and metabolism but also transport, receptor binding, and intracellular signaling. It is at the level of the hormone receptor that the genetic symphony finds its crescendo.

The receptor is the final arbiter of a hormone’s message; its structure and sensitivity, dictated by its own genetic code, determine the ultimate physiological response. An inquiry into the genetics of hormone metabolism is incomplete without a parallel investigation into the genetics of hormone action.

The androgen receptor (AR) serves as a paradigmatic example of this principle. Encoded by the AR gene on the X chromosome, this receptor is the cellular target for androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). The biological effect of testosterone is contingent upon its ability to bind to the AR and initiate a cascade of downstream gene transcription.

Therefore, the functionality of the AR itself is a primary determinant of androgen sensitivity throughout the body. Inter-individual variability in the AR gene provides a compelling explanation for why two men with identical serum testosterone levels can exhibit markedly different phenotypes and responses to Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT).

The Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat Polymorphism

Within the first exon of the AR gene lies a polymorphic region characterized by a variable number of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats. The number of these CAG repeats is highly variable among individuals, typically ranging from 10 to 35. This repeat length is inversely correlated with the transcriptional activity of the androgen receptor.

A shorter CAG repeat length results in a more sensitive and efficient receptor, capable of initiating a stronger biological response to a given amount of androgen. Conversely, a longer CAG repeat length produces a less sensitive receptor, requiring a higher concentration of androgen to achieve the same effect.

This single genetic variation has profound systemic implications. A man with a shorter CAG repeat length may exhibit signs of robust androgenic activity even with testosterone levels in the lower end of the normal range. His body is simply more efficient at using the testosterone he has.

In contrast, a man with a longer CAG repeat length may experience symptoms of hypogonadism, such as fatigue and low libido, despite having testosterone levels in the mid-to-upper range of normal. His cellular machinery is less sensitive to the androgen signal. This phenomenon of receptor sensitivity provides a crucial layer of context to standard laboratory testing and helps validate the experience of the symptomatic individual whose bloodwork appears “normal.”

What Are the Clinical Implications of AR Genotyping?

The clinical utility of AR genotyping is most apparent in the context of TRT. An individual with a long CAG repeat length may require a higher therapeutic dose of testosterone to achieve symptomatic relief. Their target for “optimal” free testosterone may be in the upper quartile of the reference range, as this is the level required to sufficiently activate their less sensitive receptors.

For these individuals, protocols may also be designed to optimize levels of DHT, a more potent androgen, to further amplify the signal at the receptor level. Without this genetic information, a clinician might undertreat the patient based on conventional laboratory targets, leaving them with persistent symptoms.

The genetic architecture of the androgen receptor itself is a primary determinant of the body’s response to testosterone.

Conversely, a patient with a short CAG repeat length may be highly sensitive to TRT. They might achieve full symptomatic resolution at a more conservative dose, and they may also be more susceptible to androgen-related side effects, such as erythrocytosis or adverse lipid profile changes.

For these individuals, a “less is more” approach is often warranted, with meticulous attention paid to keeping hormone levels within a physiologic sweet spot. This genetic information allows for a level of therapeutic precision that is unattainable with serum hormone analysis alone.

| SNP Identifier | Gene | Associated Pathway | Potential Clinical Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs700519 | CYP19A1 | Aromatization | Associated with variations in estradiol levels in men, influencing TRT management. |

| rs4680 | COMT | Estrogen Metabolism | The Val158Met polymorphism alters enzyme activity, affecting catechol estrogen clearance. |

| rs1044325 | ESR1 | Estrogen Receptor Alpha | Influences bone mineral density and response to estrogen, particularly in post-menopausal women. |

| rs6259 | SHBG | Hormone Transport | Associated with circulating levels of SHBG, which modulates free testosterone and estradiol. |

The integration of such molecular data into clinical practice represents a significant evolution in endocrinology. It moves the discipline toward a systems-biology perspective, where the interplay between hormone concentrations, metabolic enzyme efficiencies, and receptor sensitivities is fully appreciated. This multi-faceted analytical approach is essential for truly personalized medicine, enabling the design of hormonal optimization protocols that are not only effective but are also exquisitely tailored to the unique genetic and biochemical individuality of the person seeking care.

References

- Crandall, Carolyn J. et al. “Genetic Variation and Hot Flashes ∞ A Systematic Review.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 102, no. 8, 2017, pp. 2850-2862.

- Lehr, T. et al. “Genetic modelling of the estrogen metabolism as a risk factor of hormone-dependent disorders.” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 265, no. 3, 2001, pp. 127-133.

- Ruth, Katherine S. et al. “Genetic Regulation of Physiological Reproductive Lifespan and Female Fertility.” Trends in Genetics, vol. 37, no. 1, 2021, pp. 53-64.

- Zhu, Jing, et al. “Effect of hormone metabolism genotypes on steroid hormone levels and menopausal symptoms in a prospective population-based cohort of women experiencing the menopausal transition.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 9, 2013, pp. 3846-3855.

- Jernström, Helena, and Håkan Olsson. “The androgen receptor and its association with breast cancer risk and progression.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, vol. 95, no. 3, 2006, pp. 191-201.

- Narayanan, Ramesh, and Michael L. Mohler. “Pharmacogenomics of the Androgen Receptor.” Pharmacogenomics, vol. 12, no. 4, 2011, pp. 545-556.

- Stanworth, Robert D. and T. Hugh Jones. “Testosterone for the aging male ∞ current evidence and recommended practice.” Clinical Interventions in Aging, vol. 3, no. 1, 2008, pp. 25-44.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a new vocabulary for understanding your body’s internal dialogue. It provides a framework, grounded in molecular science, that connects your personal experience to your unique biological code. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It transforms the conversation from one of symptom management to one of systemic understanding and proactive calibration.

The goal is a state of vitality that feels authentic to you, achieved by working in concert with your body’s innate design. Your biology is not your destiny; it is your blueprint. The next step is to decide what you want to build.