Fundamentals

The decision to cease a hormonal optimization protocol represents a significant moment in your personal health architecture. It is a point where you consciously choose to ask your body to resume full control of its own intricate endocrine symphony.

You may feel a sense of uncertainty, a questioning of how your internal systems will respond after a period of external support. This feeling is entirely valid. It stems from an intuitive understanding that your body has been operating under a different set of rules.

The process you are about to witness is one of biological recalibration, a gradual reawakening of a powerful and sophisticated communication network that governs vitality, mood, and function. Your goal is to understand this process, not as a passive observer, but as an informed partner in your own physiology.

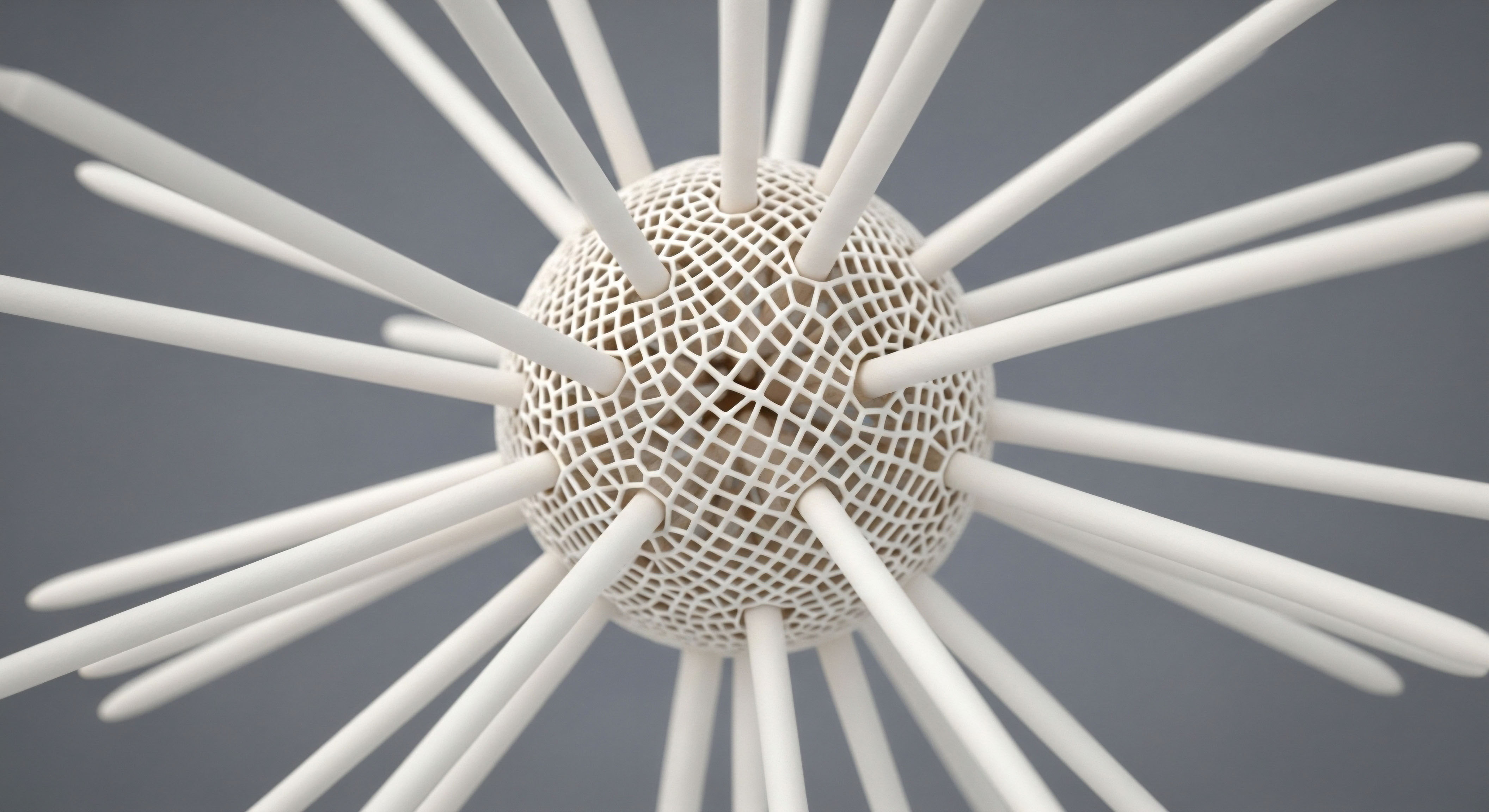

At the very center of this recalibration is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as your body’s internal executive command structure for hormone production. The hypothalamus, located deep within the brain, acts as the chief executive officer. Its primary role is to monitor the body’s overall status and issue top-level directives.

When it determines a need for hormonal action, it releases a critical memo, a chemical messenger called Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This memo travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the diligent middle manager of the operation.

Upon receiving the GnRH memo, the pituitary gland executes the command by releasing its own set of instructions into the bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones are the direct orders sent down to the factory floor ∞ the gonads (testes in men, ovaries in women).

LH is the primary signal that tells the gonads to produce testosterone or estrogen, while FSH manages the production of sperm or the maturation of ovarian follicles. This entire system is a feedback loop of profound elegance; the hormones produced by the gonads are themselves monitored by the hypothalamus, which then adjusts its GnRH memos accordingly to maintain perfect equilibrium.

The HPG axis functions as a precise biological thermostat, constantly adjusting hormonal output to maintain systemic balance.

When you begin a protocol involving exogenous hormones like Testosterone Cypionate, you are introducing a significant supply of the final product from an outside source. The hypothalamus, in its relentless efficiency, detects these high levels of circulating testosterone. It logically concludes that the factory is overproducing and that no new orders are necessary.

Consequently, it dramatically reduces or completely halts the release of its GnRH memos. The pituitary manager, receiving no directives from the executive office, stops sending LH and FSH to the gonads. The gonads, in turn, receiving no stimulation, slow down their own production and enter a state of dormancy. This is the biological mechanism of HPG axis suppression. It is a natural, predictable, and intelligent response of your body to an abundance of hormonal signals.

The recovery timeline is the period required for this entire command chain to resume its normal, self-regulated operations. When the external hormone supply is removed, the system slowly begins to notice the deficit. This is a gradual awakening. The hypothalamus must first clear the lingering signals of hormonal excess and then cautiously begin sending out its GnRH memos again.

The pituitary must regain its sensitivity to these signals and restart its own production of LH and FSH. Finally, the gonads, which have been dormant, must respond to these renewed stimuli and ramp up their own manufacturing. This sequence of events requires time.

The typical recovery period is highly variable, spanning from several months to, in some cases, over a year. The duration of your therapy, the specific compounds used, and your own unique physiology before starting the protocol are all critical factors that determine the pace of this reawakening. The process is one of patience and biological negotiation, allowing your body to rediscover its own rhythm and restore its innate hormonal architecture.

Intermediate

Understanding the general concept of HPG axis reactivation provides a solid foundation. A deeper clinical perspective requires examining the specific biochemical tools and strategies used to facilitate a smooth and efficient transition away from external hormonal support.

These protocols are designed to actively encourage the body’s endocrine system to resume its natural pulsatile signaling, mitigating the period of low hormone levels that can occur during unassisted recovery. The goal is to shorten the latency period and restore endogenous production in a structured manner, directly addressing the points of suppression within the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, while simultaneously ensuring the gonads are primed for renewed function.

Protocols for a System Reboot

A clinically guided post-therapy plan involves specific pharmacological agents that interact with the HPG axis at precise points. These are not blunt instruments; they are sophisticated modulators that help re-establish the delicate feedback loops governing your natural hormone production. The selection and timing of these agents are tailored to your specific situation, including the duration of your past therapy and your individual metabolic state.

The Role of Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) are a class of compounds that play a central part in restarting the HPG axis. Two of the most well-established SERMs in this context are Clomiphene Citrate (Clomid) and Tamoxifen. These molecules work by occupying estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus.

By doing so, they block the ability of circulating estrogen to bind to these receptors. The hypothalamus interprets this blockade as a signal of low estrogen levels. In response to this perceived deficit, it initiates a powerful compensatory mechanism ∞ it increases the production and release of GnRH.

This surge in GnRH directly stimulates the pituitary gland to produce and secrete more LH and FSH. This increased output of gonadotropins travels through the bloodstream to the testes, signaling them to ramp up testosterone production and spermatogenesis. This is a way of tricking the brain’s feedback system to your advantage, using a perceived deficiency to stimulate the entire upstream hormonal cascade.

The Function of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) is another vital tool, though it works through a completely different mechanism. While SERMs focus on stimulating the top of the command chain (the hypothalamus and pituitary), hCG works directly on the bottom (the gonads). Biochemically, hCG is a potent mimic of Luteinizing Hormone (LH).

When administered, it binds directly to LH receptors on the Leydig cells within the testes. This provides a powerful, direct stimulus for testosterone production, independent of the pituitary’s own output. Its use is particularly important for individuals who have been on long-term therapy, as it can help prevent or reverse testicular atrophy that may have occurred due to prolonged lack of LH stimulation.

Using hCG can “jump-start” the testes, keeping them functional and responsive while the upstream HPG axis is slowly recovering its own signaling rhythm. Some protocols even incorporate low-dose hCG during testosterone therapy to maintain testicular volume and function, which can significantly shorten the subsequent recovery timeline.

What Factors Influence the Recovery Timeline?

The speed and success of HPG axis recovery are subject to a range of physiological variables. Acknowledging these factors is key to setting realistic expectations and tailoring a recovery protocol effectively. The process is a biological dialogue, and these elements determine the tone and pace of the conversation.

- Duration and Dose of Therapy ∞ The length of time you were on hormonal support and the dosages used are perhaps the most significant factors. Longer periods of use and higher doses lead to a more profound and sustained suppression of the HPG axis, requiring a longer recovery period.

- Formulation of Hormones Used ∞ The type of testosterone preparation matters. Long-acting injectable esters like Testosterone Cypionate create a sustained level of testosterone and may require a longer washout and recovery period compared to shorter-acting topical gels or creams.

- Pre-Therapy Baseline Function ∞ Your hormonal status before you began therapy is a critical determinant. An individual with robust HPG function who used therapy for optimization may recover more swiftly than someone who began with pre-existing secondary hypogonadism (a condition where the pituitary or hypothalamus was already under-functioning).

- Age and Individual Physiology ∞ The general responsiveness of the endocrine system can decline with age. Genetic factors and overall metabolic health, including factors like insulin sensitivity and inflammation, also contribute to the body’s ability to recalibrate its hormonal systems.

- Concurrent Use of hCG ∞ As previously mentioned, men who used hCG concurrently with their testosterone therapy often experience a much faster recovery. They have effectively kept the gonadal “factory” online, so only the upstream signaling from the brain needs to be restored.

A Comparative Look at Recovery Timelines

To provide a clearer picture, the following table illustrates a hypothetical progression of recovery, contrasting an unassisted approach with a clinically guided protocol. The values are illustrative, representing trends rather than exact predictions for any single individual.

| Time Since Discontinuation | Unassisted Recovery (Hormone Levels) | Guided Recovery Protocol (Hormone Levels) | Subjective Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1-4 |

LH, FSH, and Testosterone levels are very low, often below the normal reference range. |

SERMs are initiated, causing a rapid rise in LH and FSH. hCG may be used, causing a direct rise in Testosterone. |

Unassisted recovery may involve significant symptoms of hypogonadism. A guided protocol often mitigates these symptoms. |

| Months 2-3 |

LH and FSH may begin to slowly rise, with a very gradual increase in Testosterone. |

LH and FSH are robustly elevated. The testes are producing significant endogenous Testosterone. |

Energy and well-being often begin to return more quickly with a guided protocol. The unassisted path can still feel challenging. |

| Months 4-6 |

The system continues its slow recovery. Spermatogenesis may begin to resume. |

The protocol may be tapered as the body’s natural pulsatile rhythm is re-established. |

A sense of stability is more likely in the guided group. The unassisted group is still in a more variable phase. |

| Months 6-12+ |

A majority of individuals will have recovered significant function, though full recovery can take up to 24 months. |

The goal is a fully self-regulated HPG axis, with all support medications withdrawn. |

Long-term stability is the endpoint for both paths, but the guided journey is designed to be faster and more comfortable. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis recovery transcends a simple timeline and delves into the neuroendocrine and cellular dynamics of its suppression and subsequent reactivation. The introduction of exogenous androgens does not simply add to the body’s hormonal pool; it fundamentally alters the intricate signaling architecture that governs endogenous production.

The recovery process is therefore a complex biological sequence involving the restoration of pulsatile hormone secretion, cellular receptor sensitivity, and steroidogenic capacity. Understanding this process at a molecular level is essential for appreciating the rationale behind clinical recovery protocols and the variability seen in patient outcomes.

Neuroendocrine Dynamics of HPG Suppression

The primary mechanism of HPG axis suppression by exogenous testosterone is the disruption of the endogenous pulsatile secretion of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. Healthy HPG function depends on GnRH being released in discrete bursts, typically every 60 to 120 minutes. This pulsatility is critical for maintaining the sensitivity of GnRH receptors on the pituitary gonadotroph cells.

When the body is exposed to continuous high levels of androgens and their aromatized metabolite, estradiol, the negative feedback mechanism becomes tonic rather than dynamic. This sustained inhibitory signal suppresses both the frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses. The pituitary, deprived of its rhythmic stimulation, downregulates its own machinery for producing and releasing Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). This results in low or undetectable serum levels of gonadotropins, effectively silencing the command signal to the gonads.

Restoring the HPG axis is fundamentally about re-establishing the precise, rhythmic pulse of neuroendocrine communication.

Cellular Consequences in the Testes

The absence of circulating LH has direct and significant consequences at the testicular level. Leydig cells, which are responsible for testosterone production, are entirely dependent on LH stimulation. Without this signal, they become quiescent, reducing or ceasing steroidogenesis.

Over prolonged periods, this can lead to a decrease in Leydig cell volume and even a reduction in their absolute number, a condition of functional atrophy. Similarly, FSH is the primary driver of Sertoli cell function, which is essential for orchestrating spermatogenesis.

The suppression of FSH impairs this process, leading to oligozoospermia (low sperm count) or azoospermia (absence of sperm). Inhibin B, a peptide hormone produced by Sertoli cells, serves as a key marker of their activity and provides negative feedback to the pituitary, specifically for FSH production. During suppression, Inhibin B levels fall, reflecting the dormant state of spermatogenesis. Recovery of spermatogenesis is therefore contingent on the restoration of FSH signaling and the subsequent reactivation of Sertoli cell function.

How Can We Measure the Recovery Process?

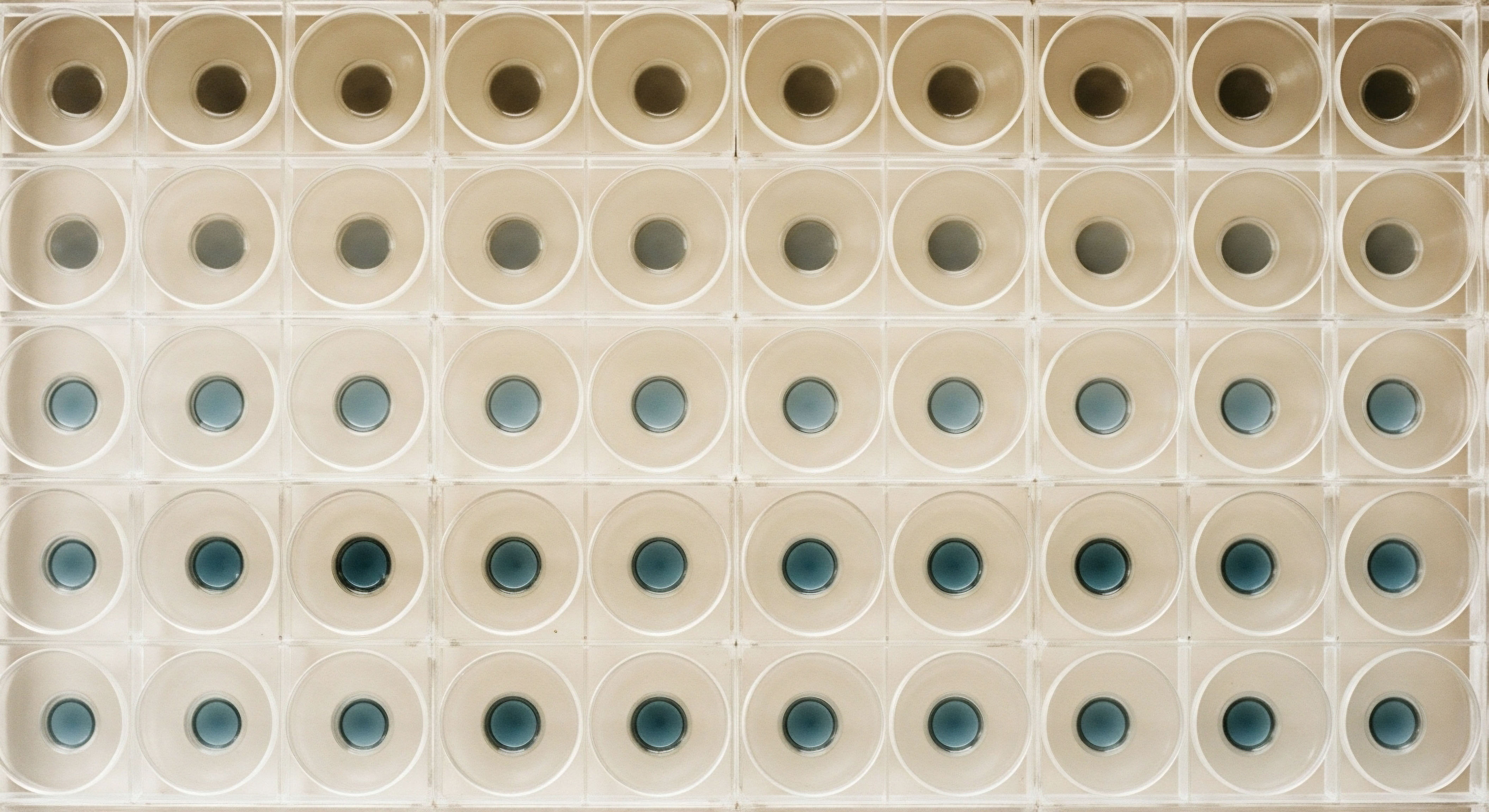

Monitoring HPG axis recovery involves a panel of specific serum biomarkers that, when interpreted together, provide a detailed picture of the system’s status. The table below outlines the key markers and their clinical significance during the recovery phase.

| Biomarker | Role in HPG Axis | Pattern During Recovery | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) |

Pituitary hormone that stimulates Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone. |

This is one of the first markers to rise, indicating the pituitary is responding to renewed GnRH signals. |

A rising LH is the primary indicator that the hypothalamic-pituitary unit is “waking up.” |

| Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) |

Pituitary hormone that stimulates Sertoli cells in the testes, driving spermatogenesis. |

Tends to rise alongside or slightly after LH. Its recovery is essential for fertility. |

FSH levels correlate with the reactivation of the machinery for sperm production. |

| Total Testosterone |

The primary androgen, produced by the Leydig cells in response to LH. |

Its rise follows the rise in LH, as the testes begin to respond to the renewed stimulation. |

This marker reflects the successful downstream effect of pituitary recovery on gonadal function. |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) |

A protein that binds to testosterone, affecting its bioavailability. |

Can fluctuate during recovery. Exogenous testosterone often suppresses SHBG, so it may rise during recovery. |

Changes in SHBG affect the interpretation of Total Testosterone levels and are important for calculating free or bioavailable testosterone. |

| Estradiol (E2) |

An estrogen metabolite of testosterone, produced via the aromatase enzyme. |

Will rise in proportion to testosterone production. Must be monitored to ensure proper androgen/estrogen balance. |

Excessive E2 relative to testosterone can cause side effects and may itself exert negative feedback on the HPG axis. |

| Inhibin B |

A peptide produced by Sertoli cells that reflects spermatogenic activity. |

A rise in Inhibin B is a direct marker of Sertoli cell function recovery and is correlated with sperm production. |

This provides a more direct assessment of fertility recovery than FSH alone. |

What Do Clinical Studies Reveal about Recovery Rates?

The existing body of research provides valuable data, though it is important to contextualize the source. Much of our understanding is extrapolated from studies on male hormonal contraception and on individuals who have used androgenic-anabolic steroids (AAS).

One prospective study of former AAS users found that after a three-month period of cessation combined with a post-cycle therapy (PCT) protocol, 79.5% of men achieved a satisfactory recovery of HPG axis function. This study also established a clear correlation between the duration, dose, and type of AAS used and the level of testosterone recovery, reinforcing the dose-dependent nature of the suppression.

Data from male contraceptive trials, where testosterone was used to suppress spermatogenesis, offer further insight. These studies suggest recovery probabilities for spermatogenesis at 67% by 6 months, 90% by 12 months, and approaching 100% by 24 months after cessation. These figures underscore the variable but generally predictable timeline of recovery, while also highlighting that a subset of individuals may experience significantly prolonged or, in rare cases, incomplete recovery.

These data collectively affirm that while spontaneous recovery is the norm, the timeline is extended and influenced by a multitude of factors, making clinically guided protocols a valuable strategy for many.

References

- Ramasamy, Ranjith, et al. “Recovery of spermatogenesis following testosterone replacement therapy or anabolic-androgenic steroid use.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 105, no. 2, 2016, pp. e23-e24.

- Lykhonosov, M. P. “Peculiarity of recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (hpg) axis, in men after using androgenic anabolic steroids.” Problems of Endocrinology, vol. 66, no. 4, 2020, pp. 57-64.

- Mills, M. J. et al. “The effect of metformin on the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis in men with late-onset hypogonadism.” Andrology, vol. 9, no. 1, 2021, pp. 265-272.

- Schulman, R. N. & Lipshultz, L. I. “Recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis after testosterone therapy.” Asian Journal of Andrology, vol. 18, no. 3, 2016, pp. 343-348.

- Coward, R. M. & Rajanahally, S. “Management of the man with secondary hypogonadism due to testosterone supplementation.” Current Urology Reports, vol. 18, no. 10, 2017, p. 81.

Reflection

You have now explored the intricate biological landscape of your body’s endocrine system, from its fundamental communication principles to the sophisticated clinical strategies designed to support its function. This knowledge is a powerful asset. It transforms uncertainty into understanding and provides a framework for interpreting the signals your body sends.

The path you are on, whether it involves continuing, modifying, or ceasing a therapeutic protocol, is uniquely yours. The timelines and mechanisms we have discussed are the map, but you are the cartographer of your own territory. Consider what vitality means to you. What are your personal goals for your health, energy, and function?

The information presented here is the first step in a dialogue ∞ a dialogue between you and your body, and between you and the clinical experts who can help guide your journey. Your biology is not a static set of instructions; it is a dynamic, responsive system. Armed with this deeper knowledge, you are better equipped to be an active participant in its lifelong calibration.