Fundamentals

Many individuals navigating their personal wellness protocols experience a deep desire for clarity regarding the body’s intricate responses. A common question arises concerning the pace of physiological adaptation, particularly the timeframe for observing significant changes in Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) levels through lifestyle interventions.

Your experience of seeking tangible progress, of sensing shifts within your own biological systems, is entirely valid and deeply understood. The journey toward hormonal recalibration is not always linear, yet it offers profound insights into your internal regulatory mechanisms.

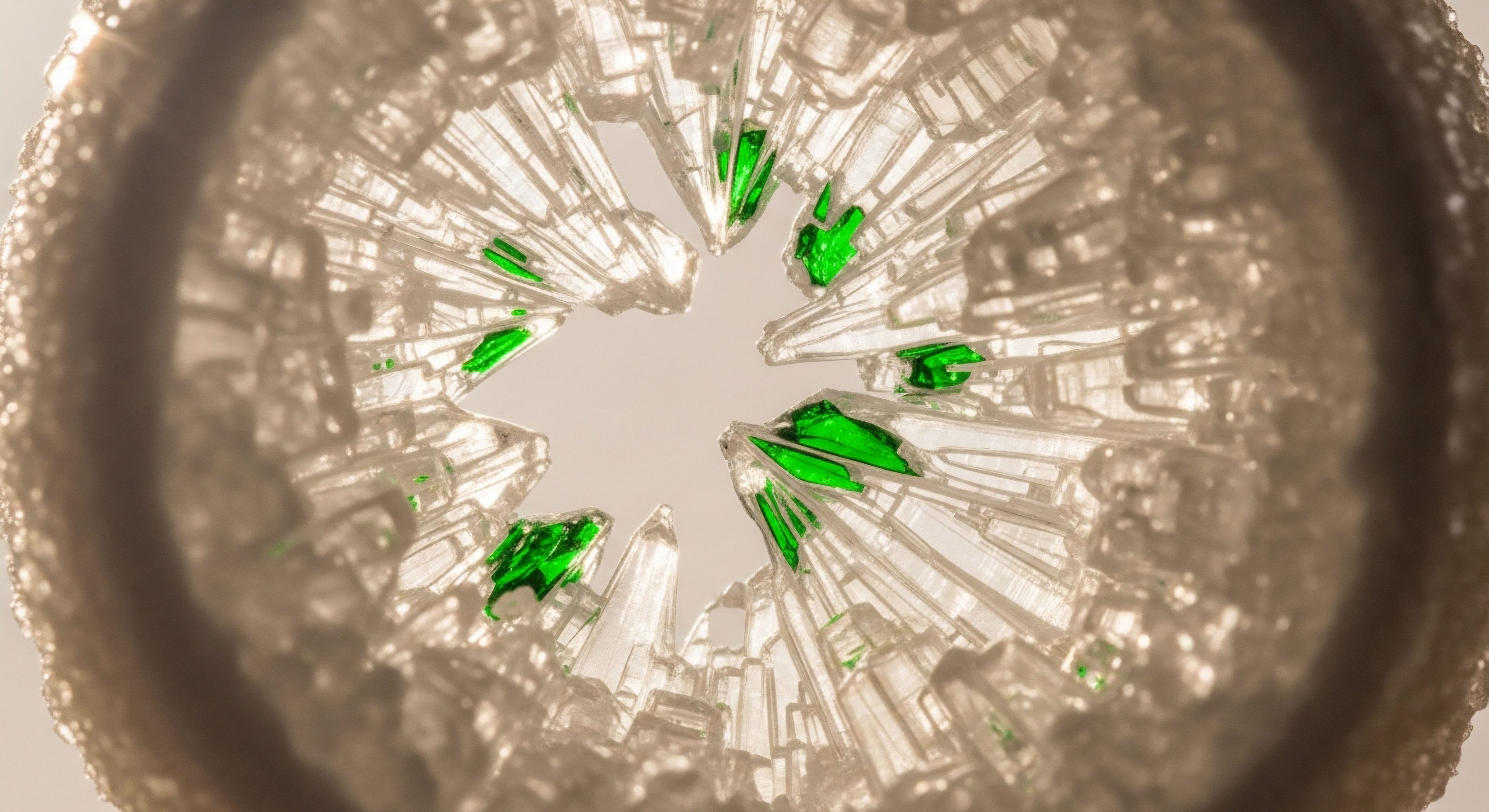

Sex Hormone Binding Globulin, a glycoprotein primarily synthesized by the liver, serves as a pivotal determinant of sex steroid bioavailability within the circulatory system. This protein acts as a sophisticated transport mechanism, binding with high affinity to androgens, such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone, and estrogens, including estradiol.

The binding capacity of SHBG directly influences the fraction of these vital hormones that remains “free” and biologically active, thereby governing their access to target tissues throughout the body. Understanding this dynamic is foundational to comprehending how changes in SHBG can profoundly impact overall vitality and metabolic function.

Significant modifications in circulating SHBG levels through dedicated lifestyle shifts are indeed achievable, typically becoming apparent within a span of several weeks to a few months. A comprehensive recalibration of the endocrine system, however, often extends over a longer period, reflecting the body’s adaptive intelligence and the complex interplay of various physiological axes. The initial responses offer encouraging markers of progress, while sustained effort drives more enduring systemic adjustments.

SHBG, a liver-produced protein, governs sex hormone availability, with lifestyle interventions showing measurable changes within weeks to months.

Understanding SHBG as a Biomarker

The concentrations of SHBG in plasma offer more than a simple numerical value; they provide a diagnostic window into underlying metabolic and hormonal health. Low SHBG levels frequently correlate with conditions characterized by insulin resistance, such as Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).

Elevated SHBG, conversely, can sometimes accompany conditions like hyperthyroidism or certain forms of hypogonadism. The utility of SHBG as a biomarker extends beyond merely reflecting current hormonal status; it can also predict future metabolic health trajectories.

Monitoring SHBG levels, therefore, becomes an integral part of a personalized wellness protocol. This allows for a precise assessment of how the body responds to targeted interventions, providing objective data that aligns with subjective improvements in well-being. The objective is to cultivate an internal environment where hormones operate with optimal efficiency, supporting every facet of physiological function.

Intermediate

For those familiar with the fundamental role of SHBG, the next logical step involves a deeper investigation into the specific mechanisms by which lifestyle interventions orchestrate changes in its circulating levels. These interventions do not merely act superficially; they engage the body’s profound biochemical pathways, guiding the liver, the primary site of SHBG synthesis, toward a more balanced production.

This section explores the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of these adaptations, detailing the specific protocols that influence SHBG and, by extension, the bioavailability of crucial sex hormones.

How Does Nutrition Influence SHBG Production?

Dietary choices exert a profound influence on SHBG regulation, primarily through their impact on metabolic signaling pathways within the liver. Consuming a diet rich in refined carbohydrates and saturated fats can depress SHBG levels, largely mediated by the resulting hyperinsulinemia. Insulin, in elevated concentrations, acts as an inhibitory signal on hepatic SHBG gene expression. Conversely, dietary patterns emphasizing whole foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and high-quality proteins, tend to support elevated SHBG levels.

- Carbohydrate Modulation ∞ High carbohydrate diets can decrease beta-oxidation and increase lipogenesis in the liver, which subsequently inhibits SHBG expression. Reducing excessive carbohydrate intake, especially from processed sources, can therefore contribute to SHBG normalization.

- Protein Quality ∞ Adequate intake of diverse protein sources provides the necessary amino acid precursors for optimal liver function and protein synthesis, indirectly supporting SHBG production.

- Healthy Fats ∞ The type of dietary fat matters significantly. While saturated fats can negatively influence SHBG, beneficial fats, such as those found in olive oil, have been shown to regulate SHBG expression positively.

- Specific Nutritional Factors ∞ Caffeine, a widely consumed stimulant, has demonstrated the capacity to upregulate hepatic SHBG expression through pathways involving adiponectin and the AKT/FOXO1 pathway. This highlights the intricate molecular interplay between dietary components and endocrine regulation.

The Impact of Physical Activity and Body Composition

Physical activity and maintaining a healthy body composition are cornerstones of SHBG optimization. Obesity, particularly visceral adiposity, is consistently associated with lower SHBG levels. This association stems from the chronic inflammatory state and insulin resistance often accompanying excess body fat, both of which negatively influence hepatic SHBG synthesis.

Engaging in regular exercise, particularly a combination of aerobic activity and resistance training, promotes insulin sensitivity and reduces overall adiposity, thereby fostering an environment conducive to increased SHBG. The physiological state induced by fasting and exercise, characterized by increased AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity and enhanced fat oxidation (beta-oxidation), also directly promotes SHBG production.

| Intervention Category | Specific Actions | Typical SHBG Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Adjustments | Reducing refined carbohydrates, increasing whole foods, optimizing protein and healthy fat intake, caffeine consumption | Increases SHBG |

| Physical Activity | Regular aerobic and resistance exercise, fostering a “fasting state physiology” | Increases SHBG |

| Body Composition | Reducing adiposity, particularly visceral fat, improving insulin sensitivity | Increases SHBG |

| Stress & Sleep | Managing chronic stress, optimizing sleep hygiene | Supports SHBG stability (indirectly via metabolic health) |

The Role of Stress Management and Sleep Hygiene

The endocrine system functions as a highly integrated network. Chronic psychological stress, leading to sustained elevations in cortisol, can indirectly affect SHBG levels by influencing metabolic health and insulin sensitivity. Similarly, inadequate sleep disrupts circadian rhythms and glucose metabolism, potentially impacting SHBG regulation. Prioritizing stress reduction techniques and consistent, restorative sleep provides a supportive foundation for all hormonal optimization efforts, allowing the body’s intrinsic regulatory systems to function with greater precision.

What Does Individual Variability in Response Mean?

While general trends in SHBG response to lifestyle interventions are well-established, individual outcomes vary considerably. This variability stems from a complex interplay of genetic predispositions, baseline metabolic status, and the consistency and intensity of the interventions themselves. A personalized approach acknowledges these differences, emphasizing iterative adjustments based on regular biomarker monitoring and a keen awareness of subjective well-being.

Academic

To truly comprehend the timeframe for significant SHBG changes from lifestyle interventions, one must delve into the molecular and cellular underpinnings of its regulation. This exploration moves beyond correlative observations, seeking the intricate feedback loops and transcriptional controls that govern SHBG synthesis within the hepatocyte. The liver, as the primary site of SHBG production, acts as a sophisticated endocrine organ, dynamically adjusting its output in response to systemic metabolic and hormonal cues.

Hepatic SHBG Synthesis and Transcriptional Regulation

The human SHBG gene, located on chromosome 17p13.1, features a complex transcriptional control system. Its expression in hepatocytes is primarily driven by a proximal promoter, a TATA-less region containing several characterized footprint (FP) regions crucial for binding specific transcription factors. Among these, Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 Alpha (HNF4A) stands as a paramount regulator, acting as a positive transcriptional activator of the SHBG gene. The activity and abundance of HNF4A within the liver are profoundly influenced by the hepatocyte’s metabolic state.

Insulin, a key metabolic hormone, exerts a potent inhibitory effect on hepatic SHBG production. This inhibition occurs at the transcriptional level, where hyperinsulinemia, often characteristic of insulin resistance, downregulates SHBG gene expression. The molecular mechanism involves insulin signaling pathways that can reduce HNF4A activity or promote the activity of antagonistic transcription factors, thereby diminishing SHBG mRNA synthesis. Conversely, conditions promoting insulin sensitivity tend to support robust SHBG transcription.

Molecular Mechanisms of Dietary Modulation

The impact of diet on SHBG extends to specific macronutrient compositions and even individual phytochemicals. High carbohydrate diets, particularly those rich in monosaccharides like fructose, are potent inhibitors of SHBG gene expression. This effect is mediated by their capacity to induce hepatic de novo lipogenesis, which subsequently increases hepatocyte palmitate content.

Elevated palmitate levels then reduce HNF4A protein levels, thereby suppressing SHBG synthesis. This provides a precise molecular explanation for the observed inverse relationship between high carbohydrate intake and SHBG concentrations.

Conversely, compounds such as caffeine have demonstrated the ability to upregulate SHBG expression. Caffeine’s mechanism involves increasing adiponectin production in adipose tissue, which then acts on the liver to increase beta-oxidation and decrease lipogenesis. These metabolic shifts collectively enhance HNF4A activity, culminating in increased SHBG gene transcription. This intricate cascade illustrates how specific dietary components can fine-tune hepatic gene expression, impacting systemic hormone regulation.

Genetic Polymorphisms and SHBG Variability

Individual differences in SHBG levels and their response to lifestyle interventions are not solely a function of environmental factors; genetic variation also plays a substantial role. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) within the SHBG gene itself, as well as in genes involved in its regulation, can influence circulating SHBG concentrations. For example, specific SNPs have been associated with both SHBG levels and the future risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, suggesting a direct role for SHBG in glucose homeostasis.

Twin studies consistently demonstrate a significant genetic influence on SHBG levels, with heritability estimates ranging considerably depending on the population and covariates. These genetic predispositions can dictate an individual’s baseline SHBG levels and modulate the magnitude and speed of their response to lifestyle modifications. Understanding these genetic factors allows for a more tailored and realistic expectation of outcomes within personalized wellness protocols.

| Regulatory Factor | Mechanism of Action | Impact on SHBG Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin | Inhibits HNF4A activity, promotes lipogenesis | Decreased |

| HNF4A | Positive transcriptional activator of SHBG gene | Increased |

| Fructose (High Intake) | Induces hepatic de novo lipogenesis, reduces HNF4A | Decreased |

| Caffeine | Increases adiponectin, enhances beta-oxidation, boosts HNF4A | Increased |

| Thyroid Hormones | Stimulate SHBG production | Increased |

Connecting SHBG to the Broader Endocrine System

SHBG does not exist in isolation; it functions as an integral component of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and the broader metabolic landscape. Perturbations in SHBG levels can cascade throughout the endocrine system, influencing the availability of sex hormones for receptor binding and feedback regulation.

For instance, low SHBG, often seen with insulin resistance, results in a higher fraction of free testosterone, which can contribute to hyperandrogenic states in women (e.g. PCOS) or, paradoxically, mask functional hypogonadism in men by artificially elevating free testosterone calculations despite low total testosterone.

The therapeutic strategies within hormonal optimization protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or peptide therapies, often aim to re-establish a more favorable hormonal milieu where SHBG levels align with optimal free hormone concentrations. By meticulously addressing lifestyle factors that modulate SHBG, clinicians and individuals collaboratively work toward a biochemical recalibration that supports not only hormonal balance but also systemic metabolic resilience.

This profound understanding empowers individuals to engage with their health journey, making informed decisions that resonate at the cellular level.

References

- Ramachandran, S. Hackett, G. I. Strange, R. C. et al. (2019). Sex Hormone Binding Globulin ∞ A Review of its Interactions With Testosterone and Age, and its Impact on Mortality in Men With Type 2 Diabetes. Sex Med Rev, 7(4), 669-678.

- Sáez-López, M. J. et al. (2024). Recent Advances on Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Regulation by Nutritional Factors ∞ Clinical Implications. Mol Nutr Food Res, 68(13), e2300898.

- Hopps, E. et al. (2015). Novel insights in SHBG regulation and clinical implications. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 26(10), 540-547.

- Sáez-López, M. J. et al. (2024). The Recent Advances on SHBG Regulation by Nutritional Factors. Int J Mol Sci, 25(13), 7050.

- Hackett, G. I. et al. (2019). Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Genetic Variation ∞ Associations with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 104(11), 5461-5472.

- Fung, M. M. et al. (1997). Changes in sex hormone-binding globulin, insulin, and serum lipids in postmenopausal women on a low-fat, high-fiber diet combined with exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 82(9), 2919-2923.

- Cho, N. H. et al. (2015). Genetic effects on serum testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin in men ∞ a Korean twin and family study. Asian J Androl, 17(6), 939-943.

Reflection

The understanding you have cultivated regarding SHBG and its intricate relationship with lifestyle interventions represents a significant stride in your health journey. This knowledge is not merely academic; it is a lens through which to view your own biological systems, offering a profound sense of agency.

Consider this exploration a foundational step, a recalibration of your internal compass. Your unique physiology dictates a personalized path, one where insights gleaned from science merge with your lived experience. The pursuit of optimal vitality is an ongoing dialogue with your body, a conversation that becomes clearer and more empowering with each informed decision.