Fundamentals

Your body operates as an intricate, self-regulating system. The quest for well-being is a personal journey of understanding its signals and providing the necessary support for it to function optimally. When we extend this concept to the workplace, we encounter a similar dynamic system, one that seeks to balance the health of its members with the principles of autonomy and privacy.

The “De Minimis” Incentive Proposal emerged from a deep, systemic tension within this environment. It represents a critical examination of a single, powerful question ∞ at what point does an encouragement to share personal health information become a pressure that compromises an individual’s voluntary choice?

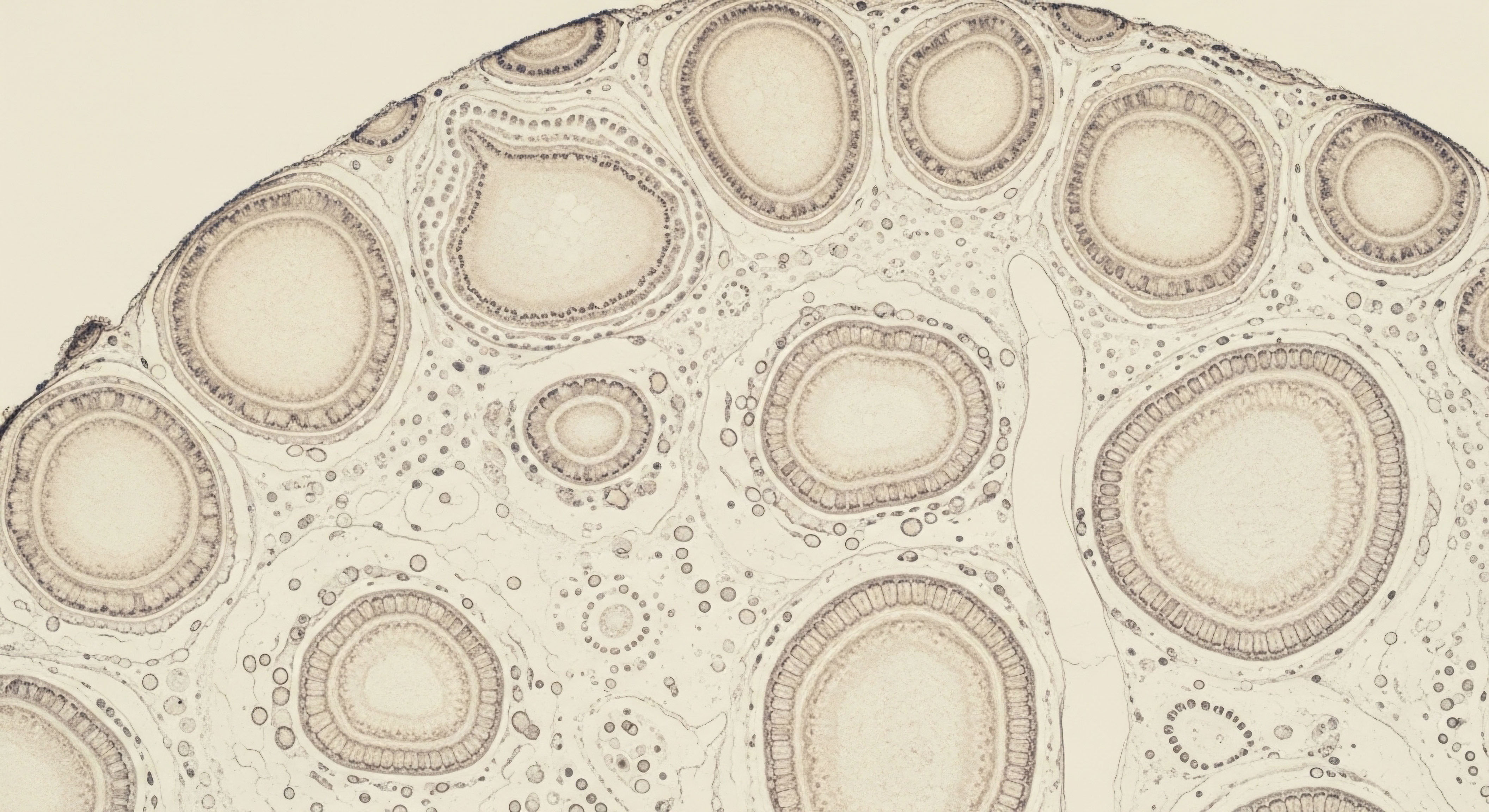

Consider the architecture of workplace wellness initiatives. Many are designed to gather information through biometric screenings or health risk assessments. This data can be immensely valuable, forming the basis of a personalized map toward improved vitality. The information, however, is profoundly personal, touching upon the very core of one’s physical and genetic makeup.

The Americans with Disabilities Act Meaning ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), enacted in 1990, is a comprehensive civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities across public life. (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act Meaning ∞ The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) is a federal law preventing discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment. (GINA) stand as guardians of this personal space, establishing a clear principle that any employee’s participation in a program that collects such data must be entirely voluntary. The “De Minimis” proposal directly addressed the biochemistry of that word, “voluntary.”

The proposal sought to define the precise threshold where a financial incentive shifts from a gentle nudge to an undeniable force.

The term “de minimis,” derived from the legal maxim de minimis non curat lex (“the law does not concern itself with trifles”), was proposed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission An employer’s wellness mandate is secondary to the biological mandate of your own endocrine system for personalized, data-driven health. (EEOC) as a new standard.

This standard would permit only trivial incentives, such as a water bottle or a gift card of very modest value, for wellness programs Meaning ∞ Wellness programs are structured, proactive interventions designed to optimize an individual’s physiological function and mitigate the risk of chronic conditions by addressing modifiable lifestyle determinants of health. that ask for protected health information without being part of a formal group health plan. This was a direct response to a foundational instability in the regulatory environment.

For years, a different set of rules under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) allowed for substantial financial incentives, creating a paradox. Two different regulatory bodies offered conflicting signals on the same essential issue, leaving both employers and employees in a state of chronic uncertainty.

The proposal, though ultimately withdrawn, was significant because it attempted to create a clear, protective boundary. It was a clinical intervention designed to diagnose and treat a specific point of friction in the system.

By suggesting a “de minimis” or trivial value, the EEOC aimed to ensure that an employee’s decision to participate was driven by an intrinsic desire for health, not by a compelling financial reward that could feel coercive. Understanding this proposal is the first step in appreciating the delicate interplay between promoting collective well-being and safeguarding the deeply personal nature of each individual’s health journey.

Intermediate

To grasp the full clinical significance of the de minimis proposal, one must first understand the distinct biological pathways of wellness programs themselves. They are not a monolithic entity; rather, they are classified into two primary categories based on their operational mechanics and their relationship with an employee’s health data. This classification is the key to understanding why different regulatory frameworks apply and why the de minimis concept was targeted so specifically.

The Two Primary Modalities of Wellness Programs

The regulatory system views wellness programs through a bifurcated lens, separating them based on their fundamental design. The two categories possess different requirements and are governed by different rules, a distinction that created the conflict the de minimis proposal sought to resolve.

- Participatory Programs These programs function on the basis of access and encouragement. An employee receives a reward, if one is offered, simply for taking part in an activity. This could include completing a Health Risk Assessment (HRA), attending a nutritional seminar, or undergoing a biometric screening. The crucial element is that the reward is not tied to the results of these activities. An employee who completes an HRA receives the same incentive regardless of the health risks identified. These programs fall squarely under the purview of the EEOC when they include medical inquiries, as the ADA and GINA demand that such participation be voluntary.

-

Health-Contingent Programs These programs introduce a direct link between action and a measurable health outcome. They function as a guided pathway toward a specific health goal. To receive a reward, an employee must meet a defined standard. This category is further divided into two sub-types:

- Activity-Only Programs Require completing an activity, like a walking program or a series of health coaching sessions. While more involved than simple participation, the reward is for doing the activity, not for achieving a specific metric like weight loss.

- Outcome-Based Programs Require attaining a specific health outcome, such as lowering cholesterol to a certain level, achieving a target blood pressure, or quitting smoking. These are the most direct form of incentive-based health management.

A Tale of Two Regulators

The central conflict arises from two different sets of federal guidelines that govern these programs. The tension is a direct result of these agencies having different core missions. The de minimis proposal was an attempt to create a zone of clarity where their jurisdictions overlapped and created confusion.

The regulatory landscape for wellness incentives is governed by a fundamental divergence in philosophy between two federal agencies.

The following table illustrates the conflicting signals sent by the two primary regulatory bodies, which created the environment for the de minimis proposal.

| Regulatory Body & Governing Laws | Core Mission | Stance on Incentives | Primary Program Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) Governs ADA & GINA | Prevent discrimination based on disability and genetic information. Protect employee privacy and autonomy. | Historically cautious. Views large incentives as potentially coercive, rendering participation “involuntary” and thus violating the ADA/GINA if medical information is collected. The de minimis proposal was the ultimate expression of this view. | Participatory programs that involve disability-related inquiries or medical exams (e.g. HRAs, biometric screenings). |

| Departments of Labor, Treasury, and HHS Govern HIPAA & ACA | Promote health and prevent disease, often through cost-containment strategies in group health plans. | Explicitly permits substantial incentives. Allows rewards of up to 30% of the total cost of health coverage (and 50% for tobacco cessation programs) for meeting health goals. | Health-contingent programs (both activity-only and outcome-based) that are part of a group health plan. |

How Did the De Minimis Proposal Fit In?

The de minimis incentive proposal An employer can offer a significant vaccine incentive if it only requires proof, but not if the incentive is coercive for an employer-run program. was a surgical intervention. It was designed to resolve the paradox specifically for participatory programs that collected medical data but were not part of a HIPAA-regulated health-contingent plan.

The EEOC reasoned that if a program simply asks for sensitive information (a medical inquiry under the ADA) without the robust framework of a health-contingent plan, the only way to ensure it is truly voluntary is to make the incentive for providing that information trivially small.

It left the larger incentives for the HIPAA-governed health-contingent programs Meaning ∞ Health-Contingent Programs are structured wellness initiatives that offer incentives or disincentives based on an individual’s engagement in specific health-related activities or the achievement of predetermined health outcomes. untouched, acknowledging their separate regulatory standing. This created a clear, albeit strict, dividing line ∞ if you are asking for health data just for participation, the reward must be minimal. If you are asking an employee to achieve a health outcome within a structured group health plan, the existing HIPAA rules apply.

Academic

The 2021 de minimis incentive Meaning ∞ A De Minimis Incentive refers to the smallest discernible physiological stimulus or intervention capable of eliciting a measurable, though often subtle, biological response or adjustment within a homeostatic system. proposal cannot be understood as a mere regulatory adjustment; it was the inevitable intellectual consequence of a fundamental schism in legal philosophy, brought to a head by the U.S. District Court’s decision in AARP v. EEOC.

An academic analysis reveals that the court’s ruling was a systemic diagnosis, exposing a flawed logical foundation within the EEOC’s previous regulatory structure. The case, and the de minimis proposal that followed, forces a deeper inquiry into the operational definition of “voluntary” within the complex bio-socio-economic system of employer-sponsored health initiatives.

The Judicial Diagnosis in AARP V EEOC

In its 2017 ruling, the court performed a critical dissection of the EEOC’s 2016 regulations, which permitted wellness incentives Meaning ∞ Wellness incentives are structured programs or rewards designed to motivate individuals toward adopting and maintaining health-promoting behaviors. up to 30% of the cost of self-only health coverage. The court found these regulations “arbitrary and capricious.” The core of the court’s reasoning was a rejection of the EEOC’s stated rationale ∞ the desire to “harmonize” its rules with those of HIPAA.

The court effectively declared that this harmonization was a category error. The purpose of the ADA and GINA Meaning ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in employment, public services, and accommodations. is to prevent discrimination and protect individuals from being compelled to disclose private information. The purpose of the ACA’s wellness provisions under HIPAA is to encourage health-promoting behaviors, often with an eye toward healthcare cost containment.

Simply borrowing the 30% incentive figure from one statute and pasting it into the other, the court argued, ignored the distinct protective purpose of the ADA and GINA.

The administrative record lacked a reasoned explanation for why a 30% incentive did not render a program coercive. The court highlighted the AARP’s compelling argument that for a low-wage worker, a penalty equivalent to 30% of their insurance premium is not a choice but a powerful economic compulsion.

This pressure could disproportionately affect those with disabilities, who, on average, have lower incomes. The court remanded the rule, instructing the EEOC to build a logical case from first principles or formulate a new one. The subsequent failure to do so led to the rule’s vacatur, creating the regulatory vacuum the de minimis proposal was designed to fill.

What Is the True Nature of Voluntary Action?

The de minimis proposal represents a specific philosophical stance on the nature of voluntary action in the presence of incentives. It implicitly argues that in the context of revealing protected health information, true voluntariness can only exist in the near-total absence of financial pressure.

This perspective aligns with principles from behavioral economics, which demonstrate that human decision-making is not always rational and can be heavily influenced by framing and financial stakes. A large incentive can create a powerful cognitive bias, shifting the decision away from a careful consideration of privacy risks toward the immediate financial gain or avoidance of loss.

The proposal suggests that the integrity of a voluntary choice is inversely proportional to the magnitude of the financial incentive attached to it.

This table explores the competing philosophies on what constitutes a “voluntary” program, a central conflict in the ongoing regulatory debate.

| Philosophical Framework | Definition of “Voluntary” | View of Incentives | Underlying Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy-Centric (EEOC/ADA/GINA) | A choice made free from undue influence or coercion, where the individual feels no significant pressure to participate. | Large incentives are inherently suspect and potentially coercive, as they can overwhelm rational decision-making about privacy. This is the framework that produced the de minimis concept. | The primary goal is the protection of the individual’s right to privacy and freedom from discrimination. The potential for economic pressure to reveal health data is the chief harm to be avoided. |

| Utilitarian/Public Health (HIPAA/ACA) | The presence of a choice, even if one option is financially favored, as long as reasonable alternatives exist for those who cannot meet the standard. | Incentives are a rational and effective tool to encourage positive health behaviors that benefit both the individual and the collective by improving health and reducing costs. | The primary goal is improving population health outcomes and managing systemic healthcare costs. Individual choice is preserved through the mechanism of reasonable alternatives. |

The Unresolved Prognosis and Current State of Systemic Disequilibrium

The withdrawal of the de minimis proposal in early 2021 returned the regulatory environment to a state of profound uncertainty. The fundamental conflict diagnosed in AARP v. EEOC Meaning ∞ AARP v. remains untreated. There is currently no EEOC-defined incentive limit for participatory wellness programs Meaning ∞ Participatory Wellness Programs represent structured health initiatives where individuals actively collaborate in the design, implementation, and ongoing adjustment of their personal health strategies. that collect medical information.

This leaves employers in a precarious position, navigating a landscape where compliance with one federal law (HIPAA) could create risk under another (the ADA). Legal challenges against employers continue, operating in this gray area. The significance of the de minimis proposal, therefore, lies not in its implementation but in its intellectual clarity.

It was a bold, if ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to establish a clear, protective rule based on a coherent philosophical principle ∞ that the sanctity of private medical and genetic information Meaning ∞ The fundamental set of instructions encoded within an organism’s deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, guides the development, function, and reproduction of all cells. requires a standard of voluntariness that is almost entirely free of financial influence.

References

- Bates, John D. AARP v. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 267 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2017).

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Proposed Rule on Amendments to Regulations Under the Americans with Disabilities Act.” Federal Register, vol. 86, no. 5, 7 Jan. 2021, pp. 1166-1185.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Proposed Rule on Amendments to Regulations Under the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.” Federal Register, vol. 86, no. 5, 7 Jan. 2021, pp. 1186-1198.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Department of the Treasury. “Final Rules Under the Affordable Care Act for Programs of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention.” Federal Register, vol. 78, no. 106, 3 June 2013, pp. 33158-33200.

- Madison, Kristin M. “The Law and Policy of Employer-Sponsored Wellness Programs ∞ A New Decade of Challenge and Opportunity.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 48, no. S1, 2020, pp. 11-14.

- Schmidt, Harald, and George Loewenstein. “The Problem with Unconditional Wellness Incentives.” The American Journal of Bioethics, vol. 19, no. 9, 2019, pp. 58-60.

- Lerner, D. et al. “The high costs of poor health ∞ The business case for health and performance management programs.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, vol. 52, no. 5, 2010, pp. 489-495.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Course

The intricate legal and philosophical debates surrounding wellness incentives ultimately circle back to a deeply personal space. The information you have absorbed about these regulations is more than academic; it is a framework for understanding the systems that influence your health decisions in the workplace. This knowledge is the first, essential tool.

It empowers you to look at any wellness initiative not as a simple directive, but as a dialogue. You can now ask more precise questions, understanding the principles of autonomy, privacy, and encouragement that operate beneath the surface. Your personal health journey is a dynamic process of calibration and response. Recognizing the external pressures and incentives is the first step in ensuring the path you choose is authentically your own, guided by an internal compass toward sustained vitality and function.