Fundamentals

Your body tells a story. Every metabolic panel, every hormonal assay, every logged symptom contributes a sentence to that narrative. When you seek to optimize your health, perhaps through testosterone replacement therapy or specialized peptide protocols, you are actively attempting to revise that story. You are providing your biological systems with new instructions.

In this profoundly personal process, you often invite a third-party wellness vendor to act as a co-author. This entity, operating outside the direct confines of your primary physician’s office, supplies the tools, platforms, and sometimes the clinical oversight to facilitate your health objectives. They are the interface between you and the complex science of physiological recalibration.

The role of this vendor is to translate your goals into a functional protocol. They may supply an application for tracking your progress, coordinate telehealth consultations, or facilitate the delivery of prescribed treatments. In doing so, they become the custodians of your body’s most sensitive data.

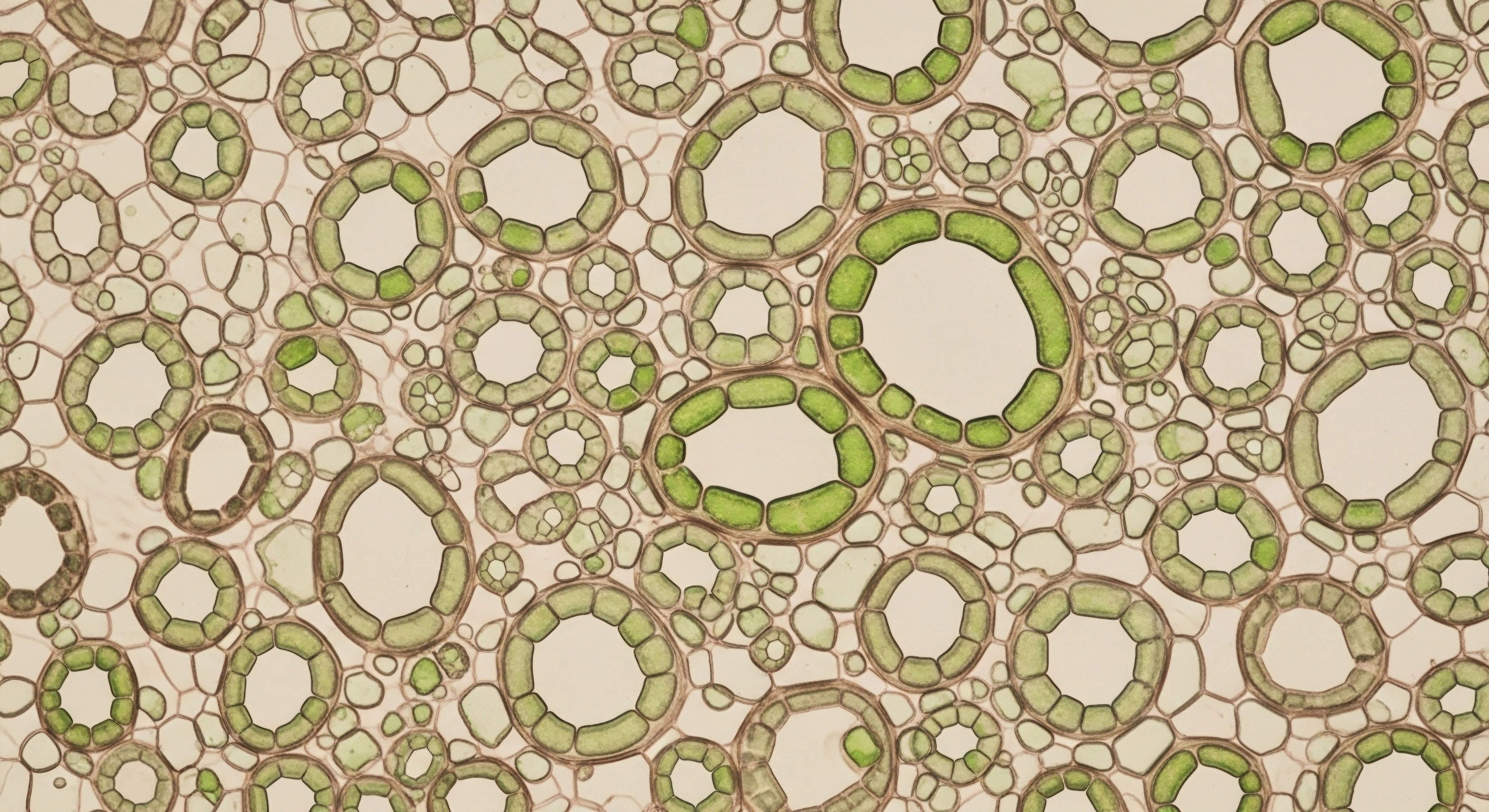

The information they collect is a digital representation of your internal state, a detailed schematic of your endocrine and metabolic machinery. This collection of data points, from testosterone levels to subjective feelings of vitality, forms a ‘data phenotype’ ∞ a digital twin of your biological self. Understanding this is the first step toward appreciating the gravity of their position.

What Is a Data Phenotype?

A data phenotype is the cumulative, digital profile of your individual health characteristics. It includes the objective numbers from lab reports, such as serum testosterone, estradiol levels, or growth hormone markers. It also encompasses the subjective inputs you provide, like sleep quality, mood fluctuations, and energy levels.

When you engage with a wellness vendor, you are continuously feeding this digital construct. This phenotype becomes a highly valuable asset, because it links hard biological data to real-world outcomes and experiences. It is the raw material from which insights about health, disease, and performance are forged. The vendor’s role, therefore, extends beyond service provision; they are architects and guardians of this intricate data structure.

The privacy policy is the foundational document that governs this relationship. It is the legal and ethical blueprint defining how your data phenotype will be handled, used, and protected. This document dictates the terms of engagement between you and the custodian of your biological narrative.

A clear, transparent, and robust privacy policy is the mechanism that ensures your personal health story remains yours. It establishes the boundaries of trust, defining who gets to read your story, under what circumstances, and for what purpose. Without this carefully defined container, your most personal information risks becoming a commodity, its narrative thread woven into datasets far beyond your control or awareness.

A third-party wellness vendor acts as a custodian for the digital representation of your biological self, and their privacy policy is the contract that defines the security of that sensitive information.

The Nature of the Agreement

Engaging a wellness vendor is an act of implicit trust. You are trusting them not only with the logistical elements of your health protocol but with the very data that defines your physiological state. The privacy policy transforms this implicit trust into an explicit agreement.

It is a declaration of the vendor’s intentions and obligations. This document outlines the types of data being collected, the methods of collection, and the specific purposes for which the data will be used. It should clearly delineate between data used for your direct care and data that might be aggregated or de-identified for research, product development, or other business intelligence purposes.

A central function of this policy is to provide you with a clear understanding of your rights. These rights typically include your ability to access your data, to request corrections, and in some cases, to demand its deletion. The policy also details the security measures the vendor has implemented to protect your information from unauthorized access or breaches.

These safeguards are the digital equivalent of a locked medical file cabinet. They are the technical and administrative systems designed to preserve the confidentiality and integrity of your data phenotype. A thorough policy will explain these measures in understandable terms, providing reassurance that your biological narrative is shielded from prying eyes.

The importance of this document is magnified in the context of hormonal and metabolic health. The data involved is exceptionally personal. It speaks to your vitality, your fertility, your mental state, and your aging process. This is not innocuous information; it is the core of your lived experience.

Consequently, the privacy policy is the primary tool you have to ensure this sensitive information is treated with the respect and confidentiality it deserves. It is the charter that holds the vendor accountable, ensuring that their role as a facilitator of your wellness journey does not conflict with their fundamental duty to protect your privacy.

Intermediate

When you commit to a sophisticated health protocol, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, you are generating a continuous stream of high-value health information. A third-party wellness vendor is often the entity that helps manage this process, and their privacy policy is the critical legal instrument that dictates the flow and control of your data.

To properly evaluate this document, one must move beyond a surface-level reading and dissect its components with a clear understanding of the regulatory landscape. The central piece of legislation in the United States governing health information is the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). However, its application to wellness vendors is complex and often misunderstood.

HIPAA’s Privacy Rule applies to “covered entities,” which are defined as health plans, health care clearinghouses, and health care providers who conduct certain electronic transactions. If a wellness vendor is operating as part of your employer’s group health plan, it is likely considered a “business associate” of a covered entity and is therefore bound by HIPAA’s stringent rules.

In this scenario, your data, known as Protected Health Information (PHI), receives robust protection. The vendor cannot share your identifiable data with your employer for employment-related decisions and must adhere to strict security standards.

The situation becomes ambiguous when the wellness vendor operates outside of this structure. Many direct-to-consumer wellness companies, apps, and platforms are not considered covered entities. They are not directly billing insurance or operating as part of a formal health plan. In these cases, HIPAA does not apply.

This is a critical distinction. The data they collect, while identical in nature to PHI, may not have the same legal protections. Instead, their practices are governed by their own privacy policy and broader consumer protection laws, such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act, which prohibits deceptive practices. This regulatory gray area makes a thorough analysis of the vendor’s privacy policy an absolute necessity for the informed patient.

Deconstructing the Privacy Policy

A well-structured privacy policy should be transparent and specific. It is a technical document, and its language must be precise. When reviewing it, you are acting as the primary auditor of your own data security. Your focus should be on several key areas.

Data Collection and Use

The policy must explicitly state what information is being collected. This is often more extensive than one might assume. It includes not only your lab results and prescription details but also your browsing history on their platform, your IP address, and any information you voluntarily disclose in surveys or communications.

The document should then specify the purpose of this collection. Legitimate purposes include providing your clinical care, processing payments, and internal operations. You should look for language that discusses secondary uses, such as “research,” “product development,” or “marketing.” The terms governing these secondary uses are of paramount importance.

The protections afforded to your health data are not universal; they depend entirely on whether the wellness vendor is legally classified as a HIPAA-covered entity.

Data Sharing and Third-Party Access

This section is arguably the most critical. The policy must identify with whom your data may be shared. Vague terms like “trusted partners” or “third-party affiliates” are red flags. A transparent policy will name the categories of third parties, such as laboratories, pharmacies, or data analytics firms.

It will also explain the legal basis for this sharing, which is typically your consent as granted by agreeing to the policy. Pay close attention to any clauses that permit the sale of de-identified or aggregated data.

While your name may be removed, research has shown that de-identified data can sometimes be re-identified by cross-referencing it with other publicly available datasets. This creates a potential pathway for your sensitive health information to be used in ways you never intended.

Below is a table outlining the typical types of data collected by a wellness vendor and the potential privacy implications associated with each.

| Data Type | Primary Use | Potential Secondary Use & Privacy Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Data (Lab Results, Prescriptions) | Managing your specific health protocol (e.g. dosing TRT). | Inclusion in large, aggregated datasets for research or sale to pharmaceutical companies. Potential for re-identification. |

| User-Reported Data (Symptom Logs, Mood) | Tracking subjective response to treatment for adjustments. | Used to build predictive models for marketing purposes, targeting users with specific supplements or services. |

| Genetic Information (If applicable) | Personalizing treatment protocols based on genetic markers. | Highly sensitive data that, if breached, has implications for you and your biological relatives. Could be used by insurance companies in the future if regulations change. |

| Platform Metadata (IP Address, Usage Patterns) | Website optimization and security. | Tracking user behavior to build a detailed consumer profile for targeted advertising, both on and off the platform. |

Understanding Data States

The language in a privacy policy often refers to different states of data. Understanding these distinctions is key to grasping the level of risk.

- Identifiable Data ∞ This is your raw data, directly linked to your name, email address, and other personal identifiers. This state should have the highest level of security and the strictest access controls.

- De-Identified Data ∞ This is data where direct identifiers like your name and social security number have been removed. However, as mentioned, the risk of re-identification exists, especially with detailed datasets containing multiple health markers.

- Aggregated Data ∞ This involves pooling your data with that of other users to create large-scale statistical summaries (e.g. “20% of our male users between 40-50 have low testosterone”). This is generally considered lower risk, but the quality of the aggregation process matters.

A vendor’s privacy policy must be explicit about which state of data is used for which purpose. The sharing or sale of identifiable data without your explicit, separate consent for a specific purpose is a significant breach of trust. The policy should grant you control over these permissions, allowing you to opt in or out of secondary data uses. This principle of granular consent is a hallmark of a user-centric privacy framework.

Academic

The proliferation of third-party wellness vendors represents a paradigm shift in the generation and custodianship of longitudinal health data. These entities, particularly those focused on hormonal optimization and metabolic health, are positioned at the confluence of direct-to-consumer healthcare and big data analytics.

The privacy policy, in this context, functions as more than a mere legal disclosure; it is the ethical and operational charter that governs the creation of vast, novel biological datasets. An academic appraisal of this document requires a multi-disciplinary lens, incorporating principles from medical ethics, data science, and regulatory law to fully comprehend its implications.

The fundamental transaction is the exchange of deeply personal physiological data for a specialized health service. The data collected ∞ ranging from serum levels of testosterone and estradiol to genomic markers and patient-reported outcomes ∞ is of immense scientific and commercial value.

It provides a granular, real-world view into the dynamic interplay of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, metabolic function, and subjective well-being. The privacy policy, therefore, must be scrutinized as the primary instrument mediating the inherent tension between patient care and data monetization. A vendor’s business model is often predicated on the secondary use of this data, making the policy’s stipulations on data anonymization and sharing the core of the ethical debate.

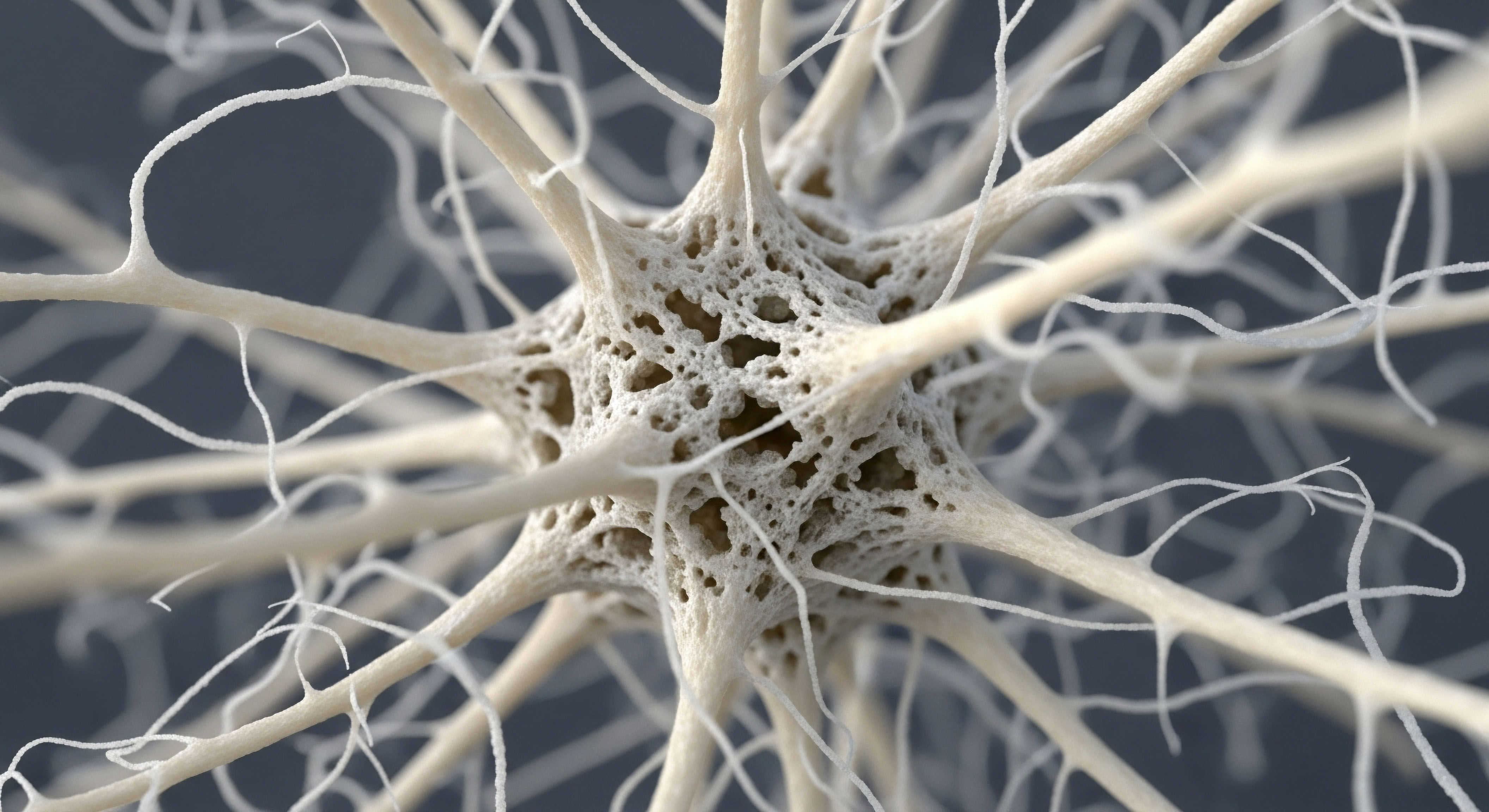

The Fallibility of Anonymization and the Specter of Re-Identification

A central pillar of many privacy policies is the assurance that shared data will be “de-identified” or “anonymized.” From a data science perspective, true anonymization of high-dimensional data is a non-trivial challenge. High-dimensional data refers to datasets with a large number of variables per individual, which is precisely what is collected in comprehensive wellness programs.

A dataset containing age, zip code, and date of a clinical visit can be sufficient to re-identify a significant portion of the U.S. population. When you add the richness of hormonal panels, specific medication protocols (e.g. Testosterone Cypionate with Anastrozole), and user-logged symptoms, the resulting data phenotype becomes a unique digital fingerprint.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule provides two pathways for de-identification ∞ “Safe Harbor,” which involves removing 18 specific identifiers, and “Expert Determination,” where a statistician certifies that the risk of re-identification is very small. Vendors not covered by HIPAA are not bound by these standards and may use proprietary or less rigorous methods.

Their privacy policies often lack specific details about the de-identification methodology used. This ambiguity is a significant point of failure. Without a clear, auditable standard, the promise of anonymity can be illusory. The potential for re-identification means that sensitive data, which may include information about fertility treatments, sexual function, or mental health status, could be linked back to an individual, creating risks of discrimination, stigmatization, or emotional distress.

The promise of data anonymization within a privacy policy is often a statistical assurance, not an absolute guarantee, especially when dealing with the unique, high-dimensional data from personalized health protocols.

What Is the Economic Value of Your Hormonal Data?

The secondary use of health data is a multi-billion dollar industry. Pharmaceutical companies, research institutions, and insurance underwriters all have a vested interest in acquiring large-scale, longitudinal health datasets. The information generated through a TRT or peptide therapy program is particularly valuable because it tracks patient outcomes over time in response to specific interventions.

This data can accelerate drug discovery, refine treatment protocols, and build predictive models for disease risk. The privacy policy dictates how, and if, the vendor can participate in this market.

The table below outlines the key stakeholders in the health data economy and the specific value they derive from the type of data a wellness vendor collects.

| Stakeholder | Type of Data Sought | Economic or Strategic Value |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Companies | Longitudinal data on drug efficacy and side effects (e.g. response to Anastrozole in a TRT protocol). | Informing Phase IV (post-market) research, identifying new drug targets, and marketing to specific patient populations. |

| Academic & Research Institutions | Aggregated, de-identified datasets for population health studies. | Studying the long-term effects of hormonal therapies, identifying correlations between lifestyle factors and hormonal health. |

| Insurance Companies & Underwriters | Risk-stratification data, predictive models of disease. | Refining actuarial tables and potentially adjusting premiums (a practice currently limited by law but a future risk). |

| Data Brokers | Any and all consumer data, including health-related information. | Creating comprehensive consumer profiles to be sold to marketers for highly targeted advertising. |

Algorithmic Bias and the Future of Personalized Medicine

Beyond individual privacy, the manner in which vendors collect and structure data has broader societal implications. The datasets being built by these companies will inevitably be used to train the next generation of artificial intelligence and machine learning models for healthcare.

If the user base of a particular wellness platform is not representative of the general population ∞ for instance, if it skews towards a specific socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or age group ∞ the resulting algorithms may be biased. An AI model trained primarily on data from affluent, middle-aged men undergoing TRT may not provide accurate or safe recommendations for other demographics.

The privacy policy rarely, if ever, addresses this issue of algorithmic fairness. It is focused on the rights of the individual user, not the collective impact of the data. However, as personalized medicine becomes more reliant on these predictive models, the construction of the underlying datasets becomes an issue of public health.

A truly forward-thinking ethical framework would require vendors to be transparent about the demographic composition of their datasets and the steps they are taking to mitigate bias. The absence of such considerations in current privacy policies highlights a critical gap between the rapid pace of technological development and the maturation of the ethical and regulatory frameworks designed to govern it.

How Can Privacy Policies Evolve?

The current model of a long, legalistic privacy policy that a user agrees to with a single click is insufficient for the sensitivity of the data being exchanged. A more ethical and robust model would incorporate principles of dynamic, granular consent.

This would involve a user interface that allows the patient to specify, on a granular level, what their data can be used for. For example, a user could consent to their data being used for their own care and for aggregated academic research, but not for internal marketing or sale to third parties.

This approach transforms the privacy policy from a static, one-time agreement into a dynamic, ongoing negotiation between the user and the vendor. It places control back in the hands of the individual whose biology is generating the data, ensuring that the role of the wellness vendor remains firmly rooted in its primary purpose ∞ to facilitate the patient’s personal health journey.

References

- Workplace Wellness Programs Put Employee Privacy At Risk. KFF Health News, 2015.

- STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES ∞ Wellness programs ∞ What. Littler Mendelson P.C.

- Wellness Apps and Privacy. Beneficially Yours, 2024.

- Corporate Wellness Programs Best Practices ∞ ensuring the privacy and security of employee health information. Healthcare Compliance Pros.

- Are Workplace Wellness Programs Secure and Confidential?. Marathon Health, 2016.

- Examining Oversight of the Privacy & Security of Health Data Collected by Entities Not Regulated by HIPAA. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016.

- Principles for Health Information Collection, Sharing, and Use ∞ A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2022.

- Ethical Issues in Patient Data Ownership. Cureus, 2021.

Reflection

Your Biology Your Narrative

You have now seen the architecture behind the agreement. You understand that when you provide your biological data to a wellness vendor, you are creating a digital extension of yourself. This data phenotype is a powerful entity, capable of informing profound personal health decisions and contributing to a broader scientific understanding. The privacy policy is the constitution that governs this digital citizen. It sets the laws of its existence, its rights, and its interactions with the wider world.

The knowledge you have gained is the first and most vital instrument in managing this relationship. It allows you to read between the lines of a legal document and see the operational reality it describes. It equips you to ask pointed questions and demand clarity. This is the foundation of genuine informed consent. Your health protocols are a deliberate and personal undertaking. The management of the data that flows from them must be equally deliberate.

Consider your own health data as a narrative. Each data point is a word, each lab panel a sentence, each month of progress a paragraph. This story is uniquely yours. As you move forward, the central question becomes ∞ Who do you trust to be its editor? Who gets to read the drafts?

And under what terms will your story be shared with the world? The answers to these questions will define the integrity of your personal health journey in an increasingly data-driven world. Your vigilance is the ultimate safeguard.