Fundamentals

You have begun a protocol of estrogen-based hormone replacement therapy, a significant and proactive step in managing your biological state. The expectation is often a direct return to vitality, a lifting of the fog, and a restoration of the energy that defines you. For many, this is precisely what happens.

Yet, for others, the experience is incomplete. You might notice that while some symptoms recede, others persist ∞ perhaps an ongoing struggle with body composition, unpredictable energy levels, or a sense of metabolic disquiet. This experience is valid, and it points toward a profound biological reality.

The introduction of estrogen is one half of a powerful equation. The other half, the variable that dictates the true scope of the outcome, is how your body’s internal environment receives and interprets these new hormonal communications.

The single most important lifestyle element to manage for a woman using estrogen-based hormonal optimization is the regulation of insulin sensitivity. This concept is the master key that unlocks the full potential of your therapy. Estrogen itself is a powerful modulator of how your body uses glucose, the primary fuel for your cells.

It helps to keep your cells responsive, or “sensitive,” to insulin, the hormone responsible for escorting glucose from your bloodstream into your tissues for energy production. When your cells are sensitive, this process is efficient. Your blood sugar remains stable, your energy is consistent, and your body is less inclined to store excess energy as fat, particularly around the midsection.

The effectiveness of estrogen therapy is deeply intertwined with the body’s ability to efficiently manage glucose through insulin sensitivity.

During the menopausal transition, declining estrogen levels inherently push the body toward insulin resistance. This is a state where cells become “deaf” to insulin’s signal. The pancreas compensates by producing more insulin, leading to high levels of both glucose and insulin in the blood.

This state of high insulin, or hyperinsulinemia, is a primary driver of inflammation, fat storage, and metabolic dysfunction. Placing estrogen back into this system is like sending a clear message to a recipient who is not listening. The message itself is correct, but its reception is impaired. Therefore, managing lifestyle is about tuning the receiver. It is the work of ensuring your cells are exquisitely receptive to the hormonal signals your therapy provides.

The Cellular Conversation between Estrogen and Insulin

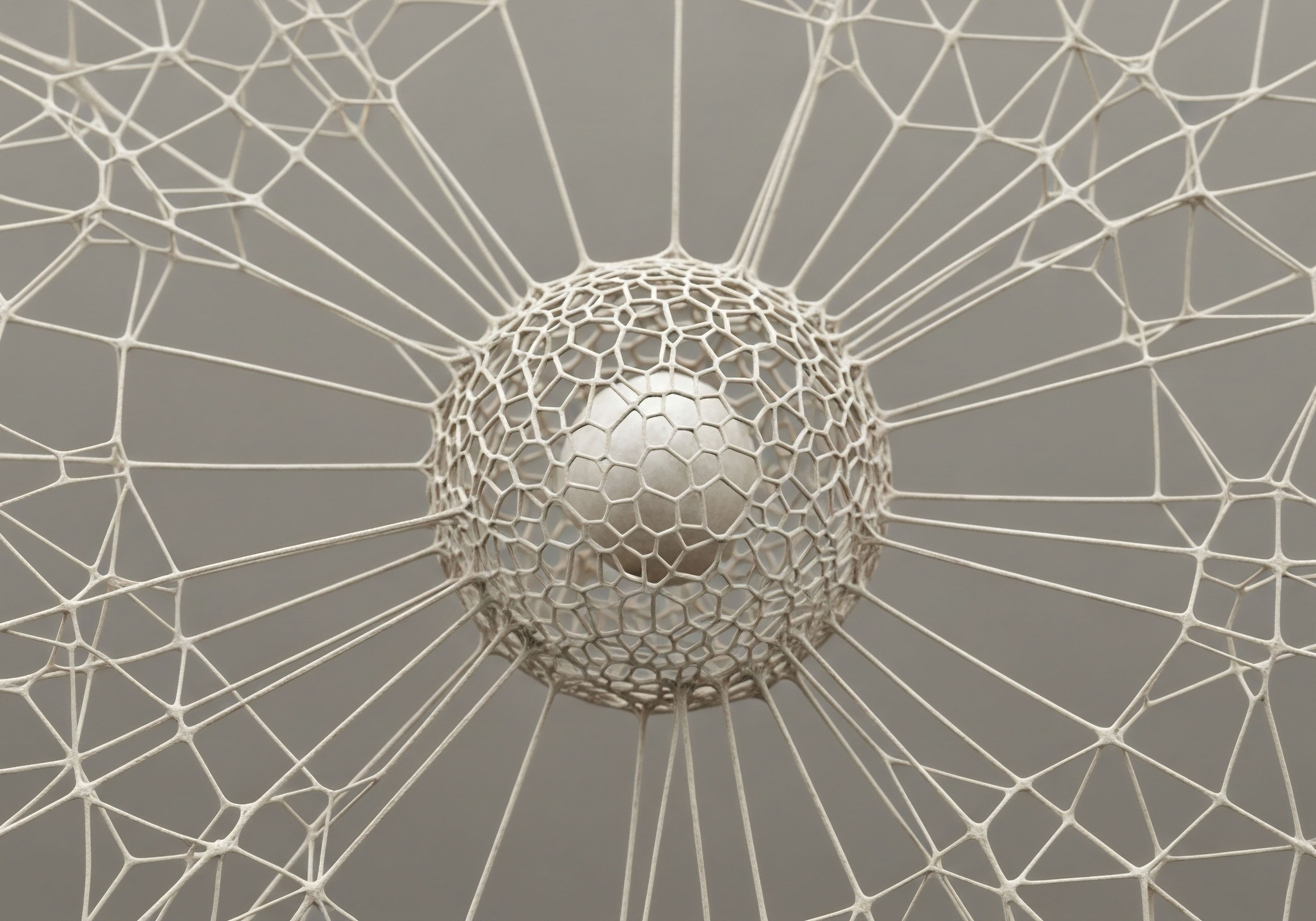

At a microscopic level, a continuous dialogue occurs between your hormones and your cells. Estrogen molecules travel through the bloodstream and bind to specific receptors on your cells, much like a key fitting into a lock. One of its downstream effects is to enhance the signaling pathway that insulin uses.

Think of estrogen as an amplifier for insulin’s voice. It helps insulin communicate more clearly with muscle and fat cells, instructing them to open their gates and welcome glucose in. This process is mediated by glucose transporters, specifically GLUT4, which move to the cell surface in response to insulin.

When you actively manage your insulin sensitivity through lifestyle, you are supporting this cellular conversation from the other side. You are ensuring the “locks” on the cells are clean and functional, and that the internal machinery responding to the “key” is well-maintained.

Lifestyle factors like nutrition, physical activity, sleep quality, and stress modulation directly impact this machinery. A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars, for example, constantly bombards the system with glucose, forcing the pancreas to shout with ever-increasing amounts of insulin. Over time, the cells defensively dampen their response to protect themselves from glucose overload, creating insulin resistance. This directly counteracts the beneficial metabolic effects of your estrogen therapy.

Why Is This the Foundational Factor?

Addressing insulin sensitivity is foundational because it sits at the crossroads of nearly every symptom and health risk associated with hormonal changes in women. It governs energy levels, body composition, cardiovascular health, and even cognitive function. By focusing on this one element, you create a cascade of positive effects that work in concert with your HRT.

- Body Composition ∞ High insulin levels are a direct command for the body to store fat, especially visceral fat, which is metabolically active and inflammatory. Improving insulin sensitivity allows the body to access and use stored fat for energy, complementing estrogen’s role in promoting a healthier fat distribution.

- Energy and Cognitive Clarity ∞ Stable blood sugar provides a steady source of fuel for the brain and body. The peaks and crashes associated with insulin resistance lead to fatigue, brain fog, and irritability. A stable metabolic environment allows for sustained energy and clearer thinking.

- Cardiovascular Protection ∞ Estrogen has a protective effect on the cardiovascular system. Insulin resistance works against this by promoting high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and inflammation in the blood vessels. Managing insulin sensitivity preserves the cardiovascular benefits of your HRT.

Your hormonal therapy is a clinical tool to re-establish a physiological baseline. Your lifestyle, centered on the principle of maximizing insulin sensitivity, is the mechanism that builds upon that baseline to restore full function and vitality. The two are inextricably linked, forming a synergistic partnership for long-term well-being.

Intermediate

Understanding that insulin sensitivity is the central lifestyle objective for women on estrogen-based HRT allows us to move from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’. The clinical application of this knowledge involves a multi-pronged approach where diet, exercise, and chronobiology are strategically manipulated to enhance cellular responsiveness.

This is not about restriction; it is about precision. Your hormonal therapy sets the stage for metabolic health, and your lifestyle choices direct the performance. The interaction is dynamic; estrogen can improve insulin signaling, but an insulin-sensitizing lifestyle allows that improvement to manifest fully, creating a powerful positive feedback loop.

The primary levers we can pull to modulate insulin sensitivity are nutritional strategy, physical stimulus, and neuro-endocrine regulation via sleep and stress management. Each of these inputs sends a distinct set of signals to your cells, influencing how they partition fuel and respond to hormonal instruction.

An effective protocol integrates all three, recognizing that they are deeply interconnected. For instance, a single night of poor sleep can induce a state of temporary insulin resistance comparable to that of a pre-diabetic individual, potentially negating the benefits of a perfectly structured diet for that day. This highlights the need for a holistic, systems-based view.

Nutritional Protocols for Metabolic Recalibration

The nutritional component of managing insulin sensitivity is centered on controlling the magnitude and frequency of insulin secretion. This is achieved by managing the quantity and quality of carbohydrates, ensuring adequate protein intake, and strategically timing meals. The goal is to create a metabolic environment characterized by stable blood glucose and moderate insulin levels.

Carbohydrate Management and Fiber Intake

The type and amount of carbohydrates consumed have the most direct impact on blood glucose and subsequent insulin demand. A diet that emphasizes high-fiber, low-glycemic index carbohydrates from whole food sources provides a slower, more controlled release of glucose into the bloodstream. This prevents the sharp spikes that can, over time, desensitize cells to insulin’s effects.

- Glycemic Load ∞ Focus on the overall glycemic load of a meal, which accounts for both the quality and quantity of carbohydrates. Combining carbohydrates with protein, fat, and fiber blunts the glycemic response.

- Sources ∞ Prioritize non-starchy vegetables, legumes, and select whole grains. These foods provide valuable micronutrients and fiber, which slows digestion and supports a healthy gut microbiome, an important secondary regulator of insulin sensitivity.

The Anabolic Role of Protein

Protein intake is critically important for women, especially those on HRT, for two primary reasons. First, it provides the building blocks for maintaining lean muscle mass, which is the body’s primary site for glucose disposal. More muscle means more storage capacity for glucose, acting as a metabolic “sink” that helps regulate blood sugar.

Second, protein has a minimal impact on blood glucose while stimulating the release of glucagon, a hormone that can help counteract some of insulin’s effects and promote satiety. Aiming for consistent protein intake at each meal helps stabilize energy and supports muscle protein synthesis.

Strategic nutritional choices, particularly those that manage carbohydrate load and ensure sufficient protein, are direct inputs for enhancing cellular insulin reception.

The Power of Physical Stimulus Exercise as Medicine

Physical activity is perhaps the most potent non-pharmacological tool for enhancing insulin sensitivity. Exercise works through both acute and chronic mechanisms. During and immediately after exercise, muscle cells can take up glucose without the need for insulin, a unique and powerful effect. Chronically, regular exercise leads to adaptations that make the entire system more efficient.

Different forms of exercise offer distinct benefits, and an optimal protocol combines them. Resistance training builds muscle mass, while aerobic exercise improves the efficiency of the cardiovascular system and the mitochondria within the cells.

The following table outlines the specific contributions of each modality:

| Exercise Modality | Primary Mechanism | Impact on Insulin Sensitivity | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance Training | Increases muscle mass (glucose sink); enhances GLUT4 transporter expression. | Long-term structural improvement in glucose disposal capacity. | 2-4 sessions per week focusing on compound movements (squats, deadlifts, presses). |

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | Depletes muscle glycogen rapidly; increases mitochondrial density. | Potent acute improvement in insulin sensitivity lasting 24-48 hours. | 1-2 short sessions per week, integrated with other training. |

| Steady-State Aerobic Exercise | Improves cardiovascular function and mitochondrial efficiency. | Enhances the body’s ability to use fat for fuel, reducing reliance on glucose. | 3-5 sessions per week of moderate-intensity activity like brisk walking, cycling, or swimming. |

How Do Sleep and Stress Influence Hormonal Efficacy?

The neuro-endocrine system, governed by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, is the third critical component. Chronic stress and inadequate sleep lead to elevated cortisol levels. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid, and its primary function in this context is to increase the availability of glucose in the bloodstream to deal with a perceived threat.

It does this by promoting glucose production in the liver and making muscle and fat cells resistant to insulin. This is a direct, powerful antagonism to the metabolic goals of your HRT and lifestyle efforts.

Managing this axis involves dedicated practices to down-regulate the stress response and prioritize sleep hygiene. These are not soft recommendations; they are clinical necessities for hormonal and metabolic health.

- Sleep Optimization ∞ Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. This involves creating a cool, dark, and quiet environment, and maintaining a consistent sleep-wake cycle to anchor the body’s circadian rhythm.

- Stress Modulation ∞ Incorporate practices like meditation, deep breathing exercises, or simply spending time in nature. These activities help shift the nervous system from a sympathetic “fight-or-flight” state to a parasympathetic “rest-and-digest” state, lowering cortisol and improving insulin sensitivity.

By integrating these three pillars ∞ nutrition, exercise, and neuro-endocrine regulation ∞ you create a robust biological framework that allows your estrogen therapy to work most effectively. You are transforming your body from a passive recipient of a hormone into an active, efficient partner in its own wellness.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the interplay between estrogen replacement therapy and lifestyle management necessitates a deep dive into the molecular and physiological mechanisms that govern metabolic homeostasis. The assertion that insulin sensitivity is the paramount lifestyle factor to manage is grounded in a systems-biology perspective that recognizes the intricate crosstalk between gonadal steroid signaling, pancreatic function, and peripheral tissue glucose uptake.

Estrogen therapy does not operate in a vacuum; its efficacy is conditional upon the metabolic phenotype of the individual, a phenotype that is sculpted by daily inputs. This section will dissect the specific pathways through which these interactions occur, moving from the cellular receptor level to whole-body metabolic flux.

The primary mediators of estrogen’s metabolic effects are its receptors, principally Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) and Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ). These receptors are expressed in key metabolic tissues, including the pancreas, liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. The binding of estradiol to these receptors initiates a cascade of genomic and non-genomic events that collectively enhance insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance.

However, the functionality of these pathways can be either augmented or attenuated by lifestyle-driven factors, particularly those that influence the insulin signaling cascade itself, such as the PI3K/AKT pathway.

The Role of Estrogen Receptors in Pancreatic and Hepatic Function

The pancreas and liver are central hubs for glucose regulation. Estrogen exerts profound effects on both. In the pancreatic islets, ERα expression in beta-cells is associated with improved insulin synthesis and secretion in response to a glucose challenge. Estradiol has been shown to protect beta-cells from apoptosis and oxidative stress, thereby preserving the organ’s functional reserve. When a woman is on HRT, the provided estrogen aims to restore this protective and efficiency-enhancing effect.

Simultaneously, estrogen acts on the liver to suppress hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis). It achieves this by down-regulating the expression of key gluconeogenic enzymes like phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase). This action is crucial for maintaining fasting blood glucose in a healthy range.

A lifestyle that promotes insulin resistance, particularly one leading to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), directly opposes this mechanism. The accumulation of lipids in the liver creates a state of local inflammation and insulin resistance, which promotes unchecked gluconeogenesis, effectively overriding estrogen’s suppressive signal. Therefore, a nutritional strategy that reduces hepatic fat accumulation is not merely beneficial; it is a prerequisite for allowing therapeutic estrogen to perform its function.

The molecular actions of estrogen on the liver and pancreas are directly compromised by lifestyle-induced metabolic dysfunction, particularly hepatic steatosis and beta-cell stress.

Skeletal Muscle and Adipose Tissue a Battleground for Glucose

Skeletal muscle is the largest site of insulin-mediated glucose disposal in the body, accounting for approximately 80% of glucose uptake under insulin-stimulated conditions. Estrogen, via ERα, promotes insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in muscle by enhancing the expression and translocation of the GLUT4 glucose transporter to the cell membrane.

This is where exercise, particularly resistance training, becomes a powerful synergistic intervention. The mechanical stress and metabolic demand of resistance exercise stimulate GLUT4 translocation through an insulin-independent pathway (via AMPK activation) and also increase the total amount of GLUT4 protein in the muscle over time.

A woman on HRT who engages in regular resistance training is therefore sensitizing her muscle tissue to glucose uptake through two distinct, complementary pathways ∞ one hormonally supported by estrogen and one physically stimulated by exercise.

Adipose tissue presents a more complex picture. Estrogen promotes the storage of fat in subcutaneous depots, which are relatively benign, and limits the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT), which is highly inflammatory and metabolically detrimental. VAT is an endocrine organ in its own right, secreting adipokines like TNF-α and IL-6 that systemically induce insulin resistance.

The decline in estrogen during menopause facilitates a shift toward VAT accumulation. While HRT helps to counteract this shift, a lifestyle high in processed foods and sedentary behavior will continue to promote visceral adiposity. This creates a situation where the therapeutic estrogen is fighting against a pro-inflammatory, insulin-desensitizing environment created by lifestyle-driven VAT. The management of VAT through diet and exercise is thus a critical factor in determining the net metabolic outcome of HRT.

How Does the Route of Administration Affect Metabolic Outcomes?

The method of estrogen delivery ∞ oral versus transdermal ∞ has significant metabolic implications that are important at a clinical level. Oral estrogen undergoes a “first-pass” metabolism in the liver. This hepatic passage can lead to increased production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which reduces the amount of free, bioavailable testosterone.

It can also impact lipid metabolism and inflammatory markers. Transdermal estrogen, conversely, is absorbed directly into the systemic circulation, bypassing the initial hepatic metabolism and more closely mimicking physiological ovarian secretion. For women with pre-existing metabolic concerns or risk factors, transdermal delivery is often preferred as it may have a more neutral or even favorable effect on insulin sensitivity and other metabolic parameters compared to oral preparations.

This choice, made with a clinician, is another layer of personalization that interacts with lifestyle. A woman on oral estrogen may need to be even more diligent with her lifestyle to offset potential negative hepatic effects.

The following table summarizes key metabolic considerations for different HRT administration routes.

| Parameter | Oral Estrogen Administration | Transdermal Estrogen Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic First-Pass Effect | Significant; influences production of binding globulins and clotting factors. | Bypassed; direct entry into systemic circulation. |

| Insulin Sensitivity | Variable effects reported; some studies suggest potential for neutral or negative impact. | Generally considered neutral to favorable; less impact on glucose metabolism. |

| SHBG Levels | Tends to increase SHBG, potentially lowering free androgen levels. | Minimal effect on SHBG levels. |

| Inflammatory Markers | Can increase levels of C-reactive protein (CRP). | Generally does not increase CRP. |

In conclusion, the scientific evidence converges on a clear point. While estrogen replacement therapy provides a foundational hormonal signal essential for metabolic health in postmenopausal women, its ultimate success is gated by the insulin sensitivity of the target tissues.

This sensitivity is not a static property but a dynamic state that is continuously shaped by the integration of nutrition, physical activity, and neuro-endocrine balance. A lifestyle protocol designed to optimize insulin signaling does not just support HRT; it enables it, allowing the full spectrum of its beneficial effects to be realized at a molecular, physiological, and experiential level.

References

- Salpeter, S. R. Walsh, J. M. E. Ormiston, T. M. Greyber, E. Buckley, N. S. & Salpeter, E. E. (2006). Meta-analysis ∞ effect of hormone-replacement therapy on components of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism, 8(5), 538-554.

- Goodman, M. P. (2013). Are all estrogens created equal? A review of oral vs. transdermal therapy. Journal of Women’s Health, 22(3), 185-195.

- Lobo, R. A. (2017). Hormone-replacement therapy ∞ current thinking. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 13(4), 220-231.

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Clegg, D. J. & Hevener, A. L. (2013). The role of estrogens in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Endocrine Reviews, 34(3), 309-338.

- Stachowiak, G. Pertyński, T. & Pertyńska-Marczewska, M. (2015). Metabolic effects of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause Review, 14(1), 53-58.

- Godsland, I. F. (2005). Oestrogens and insulin secretion. Diabetologia, 48(11), 2213 ∞ 2220.

- Davis, S. R. Castelo-Branco, C. Chedraui, P. Lumsden, M. A. Nappi, R. E. Shah, D. & Villaseca, P. (2012). Understanding weight gain at menopause. Climacteric, 15(5), 419-429.

- Ko, S. H. & Kim, H. S. (2012). Menopause-associated lipid metabolic disorders and foods beneficial for postmenopausal women. Nutrients, 4(11), 1644-1660.

Reflection

You now possess a deeper map of your own biology, one that illustrates the profound partnership between your clinical therapy and your daily choices. The information presented here is a framework for understanding the dialogue happening within your body at every moment.

It illuminates the principle that introducing a hormone is the beginning of a process, not the end of one. The true work lies in cultivating an internal environment where that hormone can speak its intended language of health and vitality with absolute clarity.

Consider the signals you send to your body each day through food, movement, and rest. How do these signals align with the goals of your hormonal protocol? Viewing your lifestyle choices through the lens of cellular communication can shift the perspective from one of rules and restrictions to one of intelligent, purposeful self-care.

You are the ultimate steward of your own physiological system. This knowledge is not a burden of responsibility, but a tool of empowerment. It is the key to moving beyond merely managing symptoms and toward the active creation of profound and lasting wellness.

Glossary

insulin sensitivity

insulin resistance

estrogen therapy

metabolic health

blood glucose

muscle protein synthesis

resistance training

estrogen replacement therapy

glucose uptake

estrogen receptor alpha

adipose tissue

pi3k/akt pathway