Fundamentals

Your journey toward understanding your body’s intricate systems is a deeply personal one. It begins with an awareness, a sense that your vitality and function could be optimized. You might feel the subtle shifts in energy, the changes in sleep quality, or the cognitive fogginess that signals a deeper imbalance.

This internal conversation is the first step in reclaiming your biological sovereignty. In this context, workplace wellness programs emerge as a structured attempt to engage with these very personal health metrics. These initiatives, which often encourage you to track biomarkers and participate in health assessments, intersect with your private world of well-being.

At the heart of this intersection lies a complex regulatory landscape, governed by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC’s role is to ensure that these programs remain truly voluntary, protecting your right to privacy and preventing discrimination based on health status.

The central question revolves around incentives ∞ at what point does a financial reward for participation become a penalty for non-participation? This is a delicate balance, one that mirrors the homeostatic equilibrium our bodies constantly strive to maintain. The current status of the EEOC’s rules on these incentives is one of deliberate pause and re-evaluation.

Proposed regulations from early 2021, which suggested limiting incentives to a “de minimis” or token value, were withdrawn. This action leaves a void in federal guidance, placing the focus back on foundational principles of choice and privacy.

The absence of specific federal rules means the voluntariness of wellness programs is currently being examined on a case-by-case basis.

What Defines a Voluntary Wellness Program?

For any wellness initiative to be considered a supportive tool rather than a mandate, its voluntary nature is paramount. The core principle is that your participation must be a product of your own informed choice, free from undue influence. An incentive, such as a discount on health insurance premiums, is intended to encourage engagement.

The regulatory challenge is to define the threshold where encouragement transforms into coercion. A truly voluntary program respects your autonomy, ensuring that declining to participate does not result in a significant financial detriment or restricted access to benefits. This principle protects individuals who may not wish to share personal health information, which is a cornerstone of medical ethics and personal privacy.

The withdrawal of the most recent EEOC guidance returns the conversation to this foundational concept. Employers are now navigating this space by referencing the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), which provide the ethical guardrails.

These laws are designed to prevent discrimination, ensuring that an employee’s health data cannot be used to their disadvantage. Therefore, the structure of a wellness program, particularly its incentive model, is being scrutinized through the lens of these anti-discrimination statutes. The focus is less on a specific dollar amount and more on the tangible impact an incentive has on an individual’s freedom to choose.

Intermediate

To appreciate the current regulatory ambiguity, it is useful to examine the recent history of the EEOC’s guidance on wellness program incentives. This history reveals a consistent tension between promoting employee health and protecting employee rights under the ADA and GINA.

The core of the issue lies in programs that ask for health information, either through biometric screenings, health risk assessments, or other medical inquiries. When an incentive is tied to providing this information, its value can influence an employee’s decision-making process, potentially undermining the principle of voluntary participation.

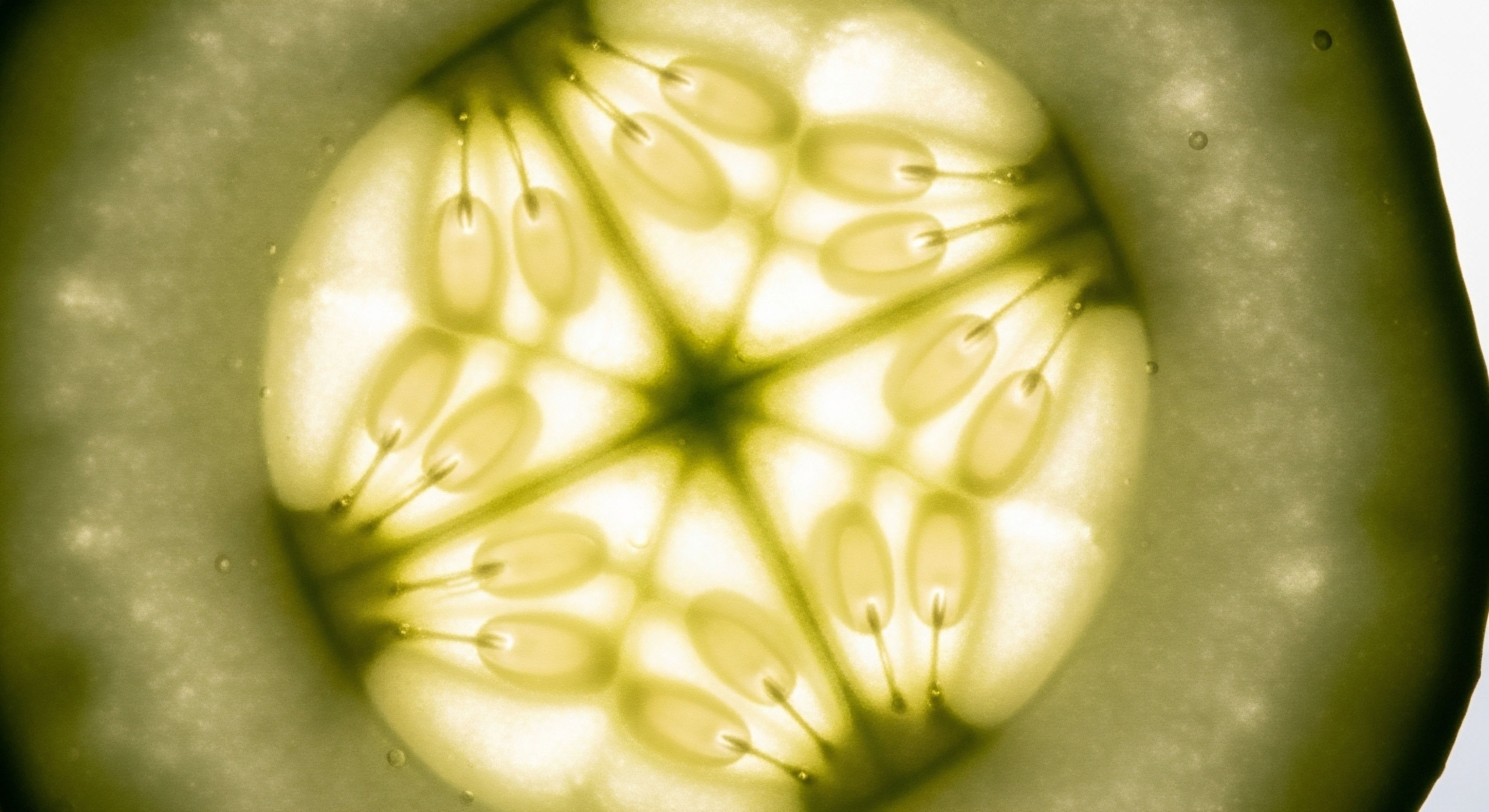

The situation can be understood by analogy to a biological feedback loop. In the endocrine system, a gland releases a hormone that travels to a target cell to produce an effect. The system has built-in negative feedback loops to prevent overproduction.

A large financial incentive can act like a powerful, synthetic signal that overrides the body’s natural regulatory mechanisms. It can create such a strong motivation that the individual’s intrinsic choice ∞ their personal “set point” for privacy and comfort ∞ is effectively bypassed. The EEOC’s struggle has been to define a “safe” level for this external signal, one that encourages without overwhelming the system of individual choice.

A Tale of Two Rule Sets

The regulatory landscape has been shaped by two key sets of rules ∞ the 2016 Final Rules and the withdrawn 2021 Proposed Rules. Understanding their differences clarifies the current state of uncertainty. The 2016 rules established a clear, quantitative limit on incentives, which was later challenged in court and vacated, leading to the current gap in guidance. The 2021 proposed rules represented a significant shift in the EEOC’s thinking, moving toward a much more conservative qualitative standard.

| Feature | 2016 Final Rules (Vacated) | 2021 Proposed Rules (Withdrawn) |

|---|---|---|

| Incentive Limit for Most Programs | Up to 30% of the total cost of self-only health insurance coverage. | Limited to “de minimis” incentives (e.g. a water bottle, a gift card of modest value). |

| Legal Justification | Interpreted the ADA’s “safe harbor” provision to allow for these incentives as part of a benefit plan. | Argued that more than a de minimis incentive renders participation involuntary. |

| Status | The incentive provisions were vacated by a federal court effective January 1, 2019. | Formally proposed in January 2021 and withdrawn in February 2021. |

What Are the Different Types of Wellness Programs?

The type of wellness program also dictates which rules apply, adding another layer of complexity. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), as amended by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also has rules for wellness programs that are part of a group health plan. These rules often coexist with, and sometimes differ from, the EEOC’s framework. The withdrawn 2021 rules attempted to align these different regulatory schemes more closely.

- Participatory Programs ∞ These programs do not require an individual to satisfy a standard related to a health factor in order to receive a reward. Examples include attending a nutrition seminar or completing a health risk assessment without any requirement to achieve a certain result. Under the withdrawn 2021 rules, these programs could only offer de minimis incentives if they required the disclosure of medical information.

- Health-Contingent Programs ∞ These programs require an individual to satisfy a standard related to a health factor to obtain a reward. They are further divided into two categories:

- Activity-Only Programs ∞ These require an individual to perform or complete an activity related to a health factor but do not require them to attain a specific outcome. Examples include walking programs or exercise challenges.

- Outcome-Based Programs ∞ These require an individual to attain or maintain a specific health outcome to receive a reward. Examples include achieving a certain cholesterol level or quitting smoking. HIPAA generally allows these programs (when part of a health plan) to offer incentives up to 30% of the cost of coverage (or 50% for tobacco cessation).

The withdrawal of the EEOC’s proposed rules means that employers offering programs that collect health information must primarily look to the ADA and GINA’s broad anti-discrimination principles for guidance. This leaves them without a clear, quantitative safe harbor, pushing them toward a more cautious approach that prioritizes the truly voluntary nature of participation.

Academic

The ongoing deliberation over wellness program incentives represents a critical juncture in labor law, public health policy, and bioethics. The core of the academic and legal debate is the interpretation of the term “voluntary” within the statutory frameworks of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA).

These laws were enacted as civil rights statutes to prevent discrimination, and their application to wellness programs forces a nuanced examination of the relationship between employer, employee, and personal health information.

The central legal conflict arises from the ADA’s allowance for “voluntary medical examinations, including voluntary medical histories, which are part of an employee health program.” The ambiguity of “voluntary” is where jurisprudence has focused. The lawsuit AARP v.

EEOC (2017) was a seminal event, wherein the court determined that the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for its 2016 rule allowing incentives of up to 30% of the cost of health coverage. The court found that such a significant financial sum could be coercive, effectively penalizing employees who chose not to disclose their private medical information. This ruling invalidated the quantitative safe harbor and set the stage for the current regulatory vacuum.

The legal discourse centers on whether a substantial financial incentive fundamentally alters the nature of consent, transforming a voluntary choice into an economic necessity.

The Jurisprudence of Coercion and Consent

The legal analysis of wellness incentives parallels the doctrine of informed consent in clinical medicine. For consent to be valid, it must be given freely, without coercion or undue influence. In the context of wellness programs, the “undue influence” is the financial incentive. Legal scholars and courts must weigh the employer’s legitimate interest in promoting a healthier workforce against the employee’s fundamental right to medical privacy and freedom from discrimination based on disability or genetic information.

The withdrawn 2021 proposed rules, with their “de minimis” standard, represented a philosophical shift toward prioritizing employee autonomy and privacy over the potential public health benefits of widespread program participation. This approach aligns with a more protective interpretation of the ADA and GINA, viewing them primarily as anti-discrimination statutes rather than public health tools.

The debate continues over whether the ADA’s insurance “safe harbor” provision ∞ which permits practices based on underwriting or classifying risks ∞ applies to wellness programs. The EEOC has historically maintained a narrow view of this provision, arguing it does not apply to most wellness programs, a position that informs its protective stance.

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | EEOC issues Final Rules under ADA and GINA. | Established a 30% incentive limit, providing a clear quantitative standard for employers. |

| 2017 | AARP v. EEOC court ruling. | The court vacates the 30% incentive limit, finding the EEOC did not adequately justify it, creating legal uncertainty. |

| 2019 | Vacatur of the 2016 incentive rules takes effect. | Employers are left with no official EEOC guidance on permissible incentive levels. |

| 2021 (Jan) | EEOC issues new Proposed Rules. | Introduced a “de minimis” standard for most wellness programs that collect health data, signaling a major policy shift. |

| 2021 (Feb) | EEOC withdraws the Proposed Rules. | Reinstates the regulatory vacuum, leaving the legal landscape to be shaped by case law and statutory interpretation. |

| Present | Absence of specific EEOC regulations. | Courts evaluate programs on a case-by-case basis, focusing on whether incentives are coercive under the ADA and GINA. |

What Is the Future of Wellness Program Regulation?

The future of EEOC regulation in this area remains uncertain. Any new proposed rules will need to grapple with the same fundamental conflict and provide a well-reasoned justification for the incentive limits they establish. This justification will likely need to be supported by economic and behavioral data to withstand judicial scrutiny.

Until new regulations are finalized, the legal environment will continue to be defined by the courts. This case-by-case approach creates a complex compliance challenge for employers, who must assess their programs not against a clear rule, but against the evolving interpretation of what it means for a program to be truly voluntary. This places a premium on conservative, ethically grounded program design that emphasizes employee well-being and autonomy over simple participation metrics.

- Emphasis on Privacy ∞ Future regulations will likely continue to strengthen privacy protections for the health data collected through wellness programs, in line with broader trends in data privacy.

- Alignment with HIPAA ∞ There will be continued pressure for the EEOC to harmonize its rules with existing HIPAA regulations to reduce the compliance burden on employers, though the differing statutory purposes of these laws make perfect alignment challenging.

- Focus on Program Design ∞ Beyond incentives, there is a growing focus on whether programs are “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease,” ensuring they provide actual value to employees rather than simply serving as a mechanism for data collection.

References

- GiftCard Partners. “EEOC Wellness Program Incentives ∞ 2025 Updates to Regulations.” 2025.

- LHD Benefit Advisors. “Proposed Rules on Wellness Programs Subject to the ADA or GINA.” March 4, 2024.

- Sequoia. ” EEOC Releases Proposed Rules on Employer-Provided Wellness Program Incentives.” January 20, 2021.

- Wellable. “EEOC Announces New Rules For Wellness Program Incentives.” June 11, 2020.

- The National Law Review. “New Wellness Programs Rules Proposed by EEOC.” January 2021.

Reflection

Where Does Your Personal Health Journey Begin?

The landscape of corporate wellness is in constant flux, reflecting a broader societal conversation about privacy, health, and autonomy. While external programs and incentives can offer structure, the true impetus for understanding your own biology must originate from within. The data points from a biometric screening are inert without your own curiosity to give them meaning.

The journey to reclaim your vitality is yours to direct. The knowledge you gain about your body’s systems, from its hormonal cascades to its metabolic pathways, is the ultimate tool for self-advocacy. This internal work is the foundation upon which all other health-related choices are built, empowering you to navigate any program or protocol with clarity and purpose.