Fundamentals

You have likely arrived here holding a lab report, a set of numbers that feels both foreign and intensely personal. One of those numbers, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin or SHBG, may be flagged as low, and this single data point might connect to a constellation of symptoms you experience daily ∞ fatigue, a change in libido, a frustrating plateau in your fitness goals, or a general sense of metabolic dysregulation.

Your first question is a practical one ∞ if you commit to changing your lifestyle, how long until this number, and more importantly, how you feel, begins to shift? The answer unfolds over two distinct timelines. Initial, measurable responses in SHBG can be observed with remarkable speed.

Focused, intensive protocols involving specific dietary changes and consistent exercise have demonstrated statistically significant increases in SHBG in as little as three weeks. This rapid response is your body’s immediate acknowledgment of a new set of inputs. It is a biological signal of positive change.

Achieving a profound and, most critically, stable alteration in your SHBG levels requires a longer view. Lasting recalibration is a process of metabolic adaptation, reflecting a fundamental improvement in how your body manages energy. Clinical studies tracking individuals over extended periods reveal that significant, sustained increases in SHBG often take between one and two and a half years to fully manifest.

This longer timeframe corresponds with durable changes in body composition, such as sustained weight loss and improved insulin sensitivity. This duration reflects the time required for your body to truly heal its metabolic machinery, particularly within the liver, which is the primary production site for SHBG. The initial weeks show a response; the subsequent months and years are when that response becomes your new baseline.

SHBG serves as a sensitive barometer for the metabolic health of your liver, directly reflecting its operational status.

Understanding the Role of SHBG

To appreciate the significance of these changes, it is essential to understand what SHBG does. Imagine your hormones, like testosterone and estradiol, as powerful messengers needing to travel through the bloodstream to reach their target tissues. SHBG is a protein that functions as a specialized transport vehicle.

It binds to these hormones, rendering them temporarily inactive during transit. The hormones that are not bound to SHBG are termed “free” or “bioavailable,” and it is this unbound fraction that can enter cells and exert its biological effects. Your SHBG level, therefore, acts as a master regulator of hormonal activity.

When SHBG levels are low, a greater proportion of your hormones are free, which can lead to symptoms of hormonal excess. Conversely, when SHBG levels are high, more hormones are bound, potentially leading to symptoms of hormonal deficiency. The goal is a state of optimal balance, where SHBG levels ensure that the right amount of hormone is available for your body’s needs.

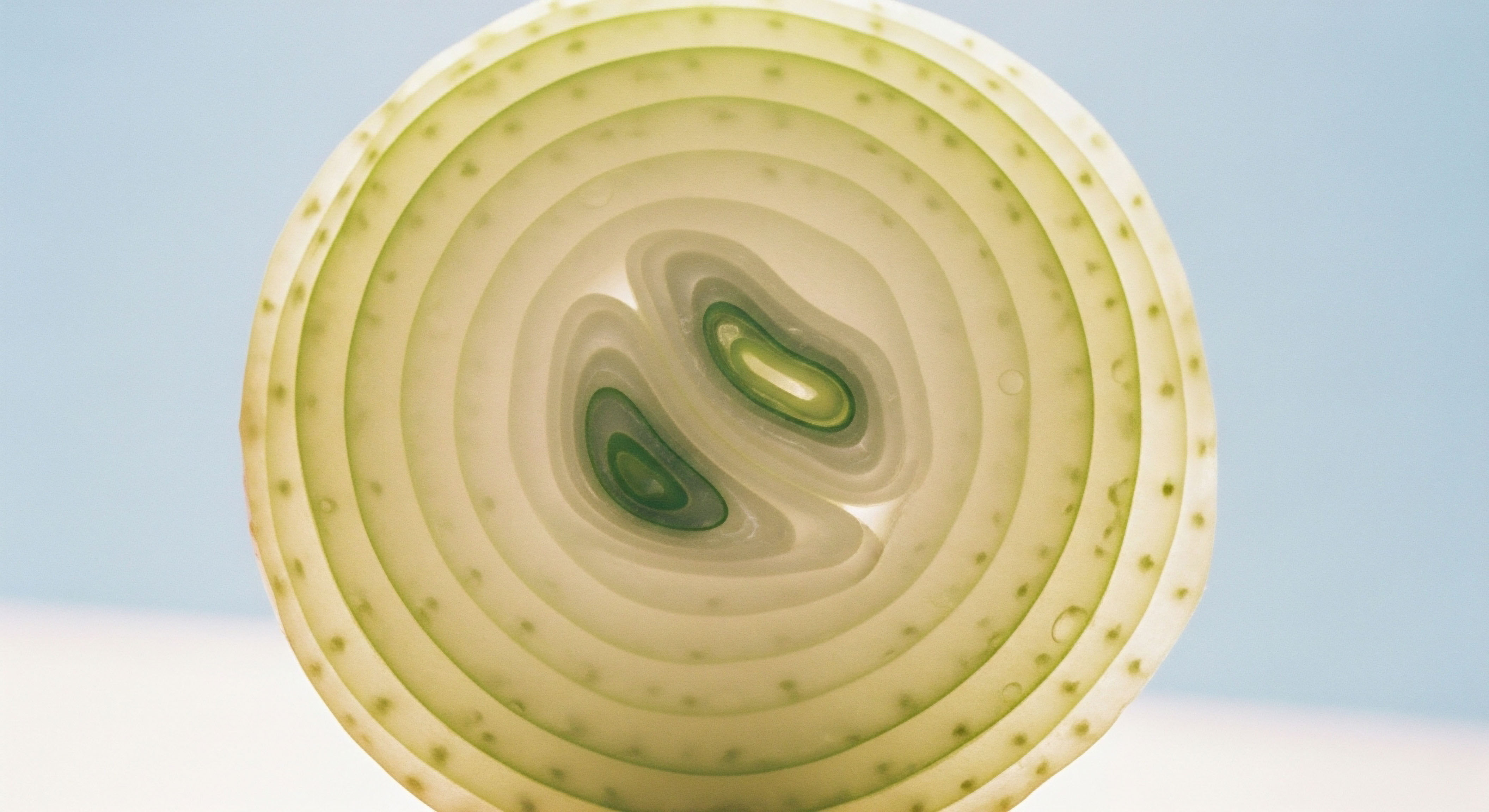

The Liver as the Command Center

The regulation of SHBG production is centered in the liver. Your liver is a metabolic powerhouse, responsible for processing nutrients, detoxifying substances, and synthesizing essential proteins, including SHBG. When the liver is burdened by an excess of certain types of energy, particularly from highly processed carbohydrates and fats, or when it is managing a state of insulin resistance, its priorities shift.

Its resources are diverted to handle this metabolic stress, and one of the consequences is a down-regulation of SHBG synthesis. A low SHBG level is therefore a direct communication from your liver, indicating that it is under metabolic strain. Lifestyle interventions work by alleviating this burden.

By changing your diet, you change the type and amount of energy the liver must process. Through exercise, you improve your body’s overall ability to utilize that energy efficiently. This combined approach allows the liver to restore its normal functions, including the robust production of SHBG.

What Are the Primary Lifestyle Interventions?

The strategies to modify SHBG levels are rooted in fundamental principles of metabolic health. They are not isolated tricks but a holistic approach to supporting your body’s innate regulatory systems. The three core pillars of intervention are diet, physical activity, and the resulting changes in body composition and insulin sensitivity.

- Dietary Composition This involves adjusting the macronutrient content of your meals to support metabolic health. A focus on high-fiber foods, adequate protein, and healthy fats reduces the glycemic load and provides the necessary building blocks for cellular repair. This approach directly impacts insulin signaling and reduces the fat storage burden on the liver.

- Physical Activity Regular movement, incorporating both aerobic and resistance training, is critical. Exercise enhances insulin sensitivity in your muscles, meaning they can absorb and use glucose from the blood more effectively. This reduces the demand on the pancreas to produce insulin and lowers circulating insulin levels, a key signal for the liver to increase SHBG production.

- Body Composition Optimization While weight loss is often a component of the process, the more precise goal is improving body composition. This means reducing excess adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat around the organs, and preserving or increasing lean muscle mass. Sustained improvements in body composition are strongly correlated with long-term normalization of SHBG levels.

These interventions work in concert. A well-formulated diet provides the right signals, exercise enhances the body’s ability to respond to those signals, and the resulting improvement in metabolic health is reflected in a healthier, more functional liver capable of producing optimal levels of SHBG.

Intermediate

For the individual already familiar with the basics of hormonal health, understanding the specific mechanisms through which lifestyle interventions modulate SHBG is the next logical step. The timeline for change is a direct consequence of how profoundly these interventions can influence the body’s intricate signaling pathways.

The rapid, three-week response seen in some studies is driven by acute shifts in insulin and hepatic glucose processing. The longer, one-to-two-year timeframe for sustained change reflects the deeper work of reversing insulin resistance and reducing hepatic steatosis (fatty liver), which are the primary controllers of SHBG synthesis. This journey is about recalibrating the sensitive conversation between your dietary inputs, your metabolic machinery, and your endocrine output.

Dietary Protocols and Their Mechanisms

The composition of your diet sends powerful instructions to your liver. Different dietary strategies can be effective because they target the same core mechanism from different angles ∞ reducing the metabolic burden on the liver and improving insulin sensitivity.

The Fiber and Protein Axis

Dietary fiber, particularly soluble fiber found in foods like oats, legumes, and apples, plays a significant role. It slows the absorption of glucose, preventing sharp spikes in blood sugar and the corresponding surge of insulin. This blunting of the insulin response is a direct signal to the liver to maintain or increase SHBG production.

Furthermore, fiber is fermented by the gut microbiome into short-chain fatty acids, which have systemic benefits for metabolic health. Protein intake also has a modulating effect. Diets with adequate protein have been shown to support healthy SHBG levels, partly by promoting satiety and aiding in the maintenance of lean muscle mass, which is crucial for insulin sensitivity. The balance of these macronutrients is key to creating a favorable hormonal environment.

Comparing Dietary Frameworks for SHBG Optimization

Different dietary models can achieve the goal of raising SHBG. Their effectiveness is rooted in their ability to lower circulating insulin and reduce the substrate for de novo lipogenesis (the creation of new fat) in the liver.

| Dietary Protocol | Primary Mechanism for SHBG Increase | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Fat, High-Fiber | Reduces total caloric and fat load on the liver, minimizing hepatic fat accumulation. The high fiber content directly improves insulin sensitivity by slowing glucose absorption. | Studies demonstrating significant SHBG increases in as little as three weeks utilized this model, emphasizing reduced fat intake and increased fiber. |

| Low-Carbohydrate / Ketogenic | Dramatically reduces glucose and subsequent insulin spikes. This directly mitigates the primary signal (hyperinsulinemia) that suppresses SHBG production in the liver. | The core principle aligns with the established mechanism of insulin-mediated SHBG suppression. By minimizing the insulin response, this approach directly targets the root cause of low SHBG in many individuals. |

Effective dietary strategies for raising SHBG converge on a single principle which is reducing the liver’s exposure to high levels of insulin.

The Central Role of Insulin Resistance

Insulin is the most powerful regulator of SHBG. In a state of health, after a meal, the pancreas releases insulin to help shuttle glucose into cells for energy. In a state of insulin resistance, the cells, particularly muscle and fat cells, become less responsive to insulin’s signal.

The pancreas compensates by producing even more insulin to overcome this resistance, leading to a condition of chronic high insulin levels known as hyperinsulinemia. The liver, which remains sensitive to insulin, receives this powerful signal. High insulin levels directly inhibit the genetic transcription of the SHBG gene in hepatocytes (liver cells).

Therefore, any lifestyle intervention that successfully raises SHBG does so primarily by reversing insulin resistance and lowering chronic insulin levels. This is the central mechanism that connects diet, exercise, and body composition to your SHBG lab value.

Exercise Prescription for Hormonal Recalibration

Physical activity is a potent tool for improving insulin sensitivity, acting independently of weight loss. It makes your muscles more efficient at taking up glucose, thereby reducing the need for high levels of insulin.

- Aerobic Training Activities like brisk walking, running, or cycling improve cardiovascular health and enhance mitochondrial function. This form of exercise creates a significant demand for glucose, helping to clear it from the bloodstream and reduce the stimulus for insulin secretion. The goal is consistency, aiming for at least 150-225 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week.

- Resistance Training Building and maintaining muscle mass through weightlifting or bodyweight exercises is metabolically crucial. Muscle is a primary site for glucose disposal. The more muscle mass you have, the more “storage space” you have for glucose, preventing it from contributing to hyperinsulinemia and hepatic fat accumulation. Combining both aerobic and resistance training provides a comprehensive strategy for metabolic improvement.

The effect of exercise is cumulative. While a single session can temporarily improve insulin sensitivity, a consistent, long-term program is what leads to the structural and functional adaptations that result in sustained increases in SHBG. The one-year timeframe noted in research reflects the period required for these deep adaptations to take hold.

Academic

From a clinical and molecular perspective, the timeline for altering Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin levels is a direct reflection of hepatic metabolic reprogramming. The rapid changes observed in short-term, intensive interventions are epiphenomena of acute substrate shifts, primarily a reduction in portal glucose and insulin concentrations.

The more clinically meaningful and durable elevation of SHBG, observed over months to years, represents a successful reversal of the molecular pathology that suppresses its synthesis ∞ hepatic steatosis and the consequent downregulation of key transcription factors. Understanding this process requires a detailed examination of the hepatocyte’s inner workings and its response to systemic metabolic cues.

The Hepatic Nexus of SHBG Regulation

The synthesis of SHBG is almost exclusively a function of the liver. The core of its regulation lies within the genetic machinery of the hepatocyte. The expression of the SHBG gene is not primarily controlled by the hormones it transports, but by the metabolic status of the liver itself.

The central molecular switch in this process is a transcription factor known as Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 alpha (HNF-4α). HNF-4α binds to the promoter region of the SHBG gene and acts as a powerful activator, initiating its transcription into messenger RNA (mRNA) and subsequent protein synthesis. Therefore, the concentration of circulating SHBG is, to a large degree, a proxy for the activity of HNF-4α within the liver.

How Does the Liver Interpret Metabolic Signals?

The activity of HNF-4α is exquisitely sensitive to the liver’s internal metabolic environment. A state of chronic energy surplus, particularly one rich in fructose and glucose, triggers a cascade that suppresses HNF-4α. This occurs through the activation of pathways involved in de novo lipogenesis (DNL), the process by which the liver converts excess carbohydrates into fatty acids.

As hepatic triglyceride content increases, a condition known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or hepatic steatosis develops. This lipotoxic environment directly inhibits HNF-4α expression and activity. Consequently, the primary driver of low SHBG is not merely high insulin, but the underlying hepatic fat accumulation that hyperinsulinemia promotes.

This provides a clear, mechanistic explanation for why lifestyle interventions focused on reducing liver fat are so effective. They restore the proper function of HNF-4α, thereby “switching on” SHBG production.

The circulating level of SHBG functions as a high-fidelity biomarker of intrahepatic fat content and the activity of the transcription factor HNF-4α.

What Is the True Relationship between Insulin and SHBG Production?

While hyperinsulinemia is strongly and inversely correlated with SHBG levels, in-vitro studies have shown that insulin itself is a relatively weak direct suppressor of the SHBG gene. The more potent mechanism of suppression is indirect. Chronic hyperinsulinemia is a primary driver of hepatic DNL.

By promoting the uptake and conversion of glucose into fat within the liver, insulin creates the lipotoxic conditions that lead to the downregulation of HNF-4α. This explains why interventions that improve insulin sensitivity throughout the body are so effective.

By reducing the chronic insulin signal, they decrease the stimulus for fat storage in the liver, allowing HNF-4α to recover and drive SHBG synthesis. This resolves the apparent paradox and clarifies that liver fat is the most direct and powerful negative regulator of SHBG production.

Molecular Regulators of SHBG Gene Expression

The regulation of the SHBG gene is a complex interplay of various factors, with the metabolic state of the hepatocyte being paramount. Understanding these inputs provides a complete picture of how systemic health translates into specific hormonal outputs.

| Regulator | Effect on SHBG Gene Expression | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4α (HNF-4α) | Strong Up-regulation | Binds directly to the SHBG gene promoter, acting as a primary transcription activator. Its own activity is suppressed by hepatic fat accumulation. |

| Insulin | Indirect Down-regulation | Promotes hepatic de novo lipogenesis, leading to liver fat accumulation, which in turn suppresses HNF-4α. It is a weak direct inhibitor. |

| Glucose & Fructose | Indirect Down-regulation | Serve as substrates for hepatic lipogenesis, contributing to the fatty liver state that suppresses HNF-4α and thus SHBG production. |

| Thyroid Hormones (T3) | Up-regulation | Directly enhances the activity of the SHBG gene promoter, which is why thyroid status can significantly impact SHBG levels. |

| Estrogens | Up-regulation | Increase SHBG gene transcription, leading to higher SHBG levels observed in states of high estrogen, such as during pregnancy or with oral estrogen use. |

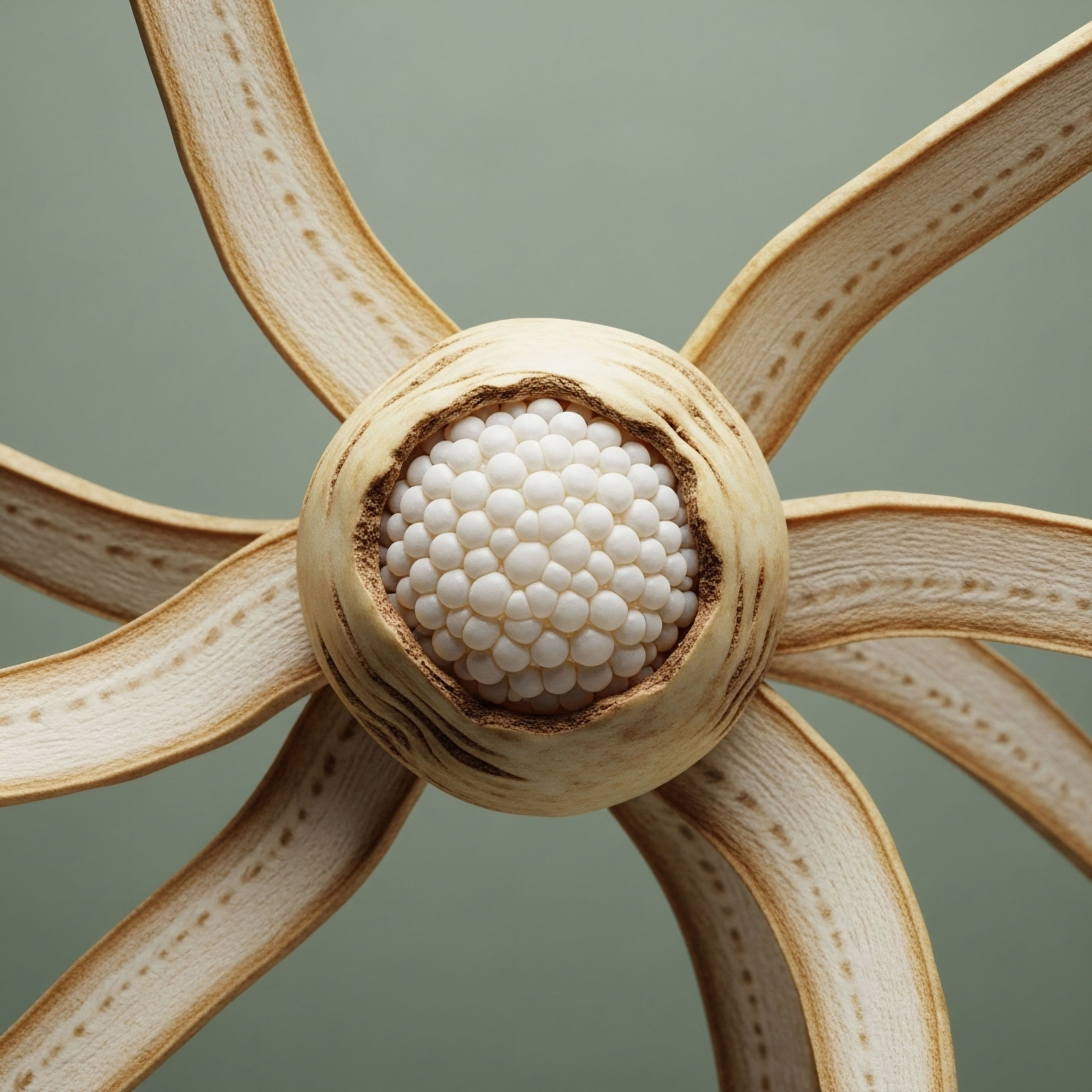

The Pathophysiological Cascade of SHBG Suppression

The journey to low SHBG follows a predictable and reversible metabolic path. Recognizing these steps is essential for designing effective, targeted interventions.

- Chronic Metabolic Overload This initial stage is characterized by a consistent surplus of energy, particularly from high-glycemic index carbohydrates and certain fats, overwhelming the body’s capacity for healthy storage and utilization.

- Development of Insulin Resistance Peripheral tissues, like muscle, become less responsive to insulin. This forces the pancreas to secrete progressively higher amounts of insulin to maintain normal blood glucose levels, resulting in systemic hyperinsulinemia.

- Induction of Hepatic De Novo Lipogenesis The liver, driven by high insulin and an abundance of substrate (glucose), accelerates the process of converting these substrates into triglycerides, leading to fat accumulation within the hepatocytes.

- Downregulation of HNF-4α Activity The resulting intrahepatic lipotoxicity creates a cellular environment that actively suppresses the expression and function of the HNF-4α transcription factor, the master switch for SHBG production.

- Reduced SHBG Transcription and Secretion With HNF-4α suppressed, the SHBG gene is no longer adequately transcribed. This leads to reduced synthesis and secretion of SHBG from the liver, resulting in the low circulating levels observed on lab reports.

The timeframe to reverse this cascade dictates the timeframe for SHBG normalization. Reducing the metabolic overload can yield acute changes in weeks. Resolving the underlying insulin resistance and, most importantly, reducing the accumulated liver fat is a longer process, requiring months to years of consistent, targeted lifestyle modification.

This explains why sustained weight loss is so strongly correlated with sustained increases in SHBG. It is a direct marker of a healthier, less fatty liver that has restored its proper endocrine function.

References

- Long, T. et al. “Long-term Weight Loss Maintenance, Sex Steroid Hormones and Sex Hormone Binding Globulin.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, vol. 28, no. 12 Supplement 2, 2019, pp. A095-A095.

- Tymchuk, C. N. et al. “Effects of diet and exercise on insulin, sex hormone-binding globulin, and prostate-specific antigen.” Nutrition and Cancer, vol. 31, no. 2, 1998, pp. 127-31.

- Longcope, C. et al. “Diet and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 85, no. 1, 2000, pp. 293-296.

- Plymate, S. R. et al. “Inhibition of sex hormone-binding globulin production in the human hepatoma (Hep G2) cell line by insulin and prolactin.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 67, no. 3, 1988, pp. 460-4.

- Kaaks, R. et al. “A randomized controlled trial of diet, physical activity and breast cancer recurrences ∞ the DIANA-5 study.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, vol. 134, no. 2, 2012, pp. 789-99.

- Selva, D. M. et al. “The transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha determines the production of sex hormone-binding globulin.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 10, 2007, pp. 3968-74.

- Simo, R. et al. “Sex hormone-binding globulin gene expression and insulin resistance.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 97, no. 5, 2012, pp. E809-13.

- Peter, A. et al. “Relationships of Circulating Sex Hormone ∞ Binding Globulin With Metabolic Traits in Humans.” Diabetes, vol. 59, no. 12, 2010, pp. 3167-73.

- Sutton-Tyrrell, K. et al. “Liver fat and SHBG affect insulin resistance in midlife women ∞ The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN).” Obesity, vol. 18, no. 12, 2010, pp. 2261-7.

- Pugeat, M. et al. “Insulin inhibits the production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in hepatocytes.” Journal of endocrinological investigation, vol. 18, no. 8, 1995, pp. 573-6.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map, detailing the biological terrain that connects your daily choices to your hormonal health. You now possess the understanding that your SHBG level is a dynamic signal, a message from the core of your metabolic engine. It reflects the health of your liver, the efficiency of your insulin, and the overall state of your internal environment. This knowledge transforms a simple number on a page into a powerful tool for insight.

Consider this understanding as the starting point of a more conscious and collaborative relationship with your own body. The path forward is one of physiological restoration. It is about systematically removing the metabolic stressors and providing the precise inputs that allow your body’s innate intelligence to re-establish balance.

This journey is unique to you, and while the principles are universal, their application is personal. The data points and timelines are guideposts, not rigid prescriptions. They illuminate the potential for profound change and empower you to take the first, most important step ∞ the decision to begin the process of recalibration, guided by insight and a commitment to your own vitality.