Fundamentals

When you find yourself grappling with concerns about male fertility or a perceived shift in your vitality, a deep understanding of your body’s intricate systems becomes paramount. This experience, often accompanied by a sense of uncertainty, can prompt a desire to reclaim a former state of function.

Spermatogenesis, the biological process responsible for sperm production, represents a delicate orchestration of hormonal signals and cellular activity. Its recovery, particularly after certain interventions or periods of imbalance, is not a simple, instantaneous event; rather, it represents a complex biological recalibration requiring precise conditions and time.

The journey toward restoring optimal male reproductive health begins with recognizing the central role of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This sophisticated communication network acts as the body’s internal messaging service, ensuring that the testes receive the correct instructions for producing both testosterone and sperm.

The hypothalamus, a region within the brain, initiates this cascade by releasing Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile fashion. This pulsatile release is a critical signal, much like a rhythmic drumbeat, that dictates the subsequent steps.

Upon receiving GnRH, the pituitary gland, a small but mighty endocrine organ situated at the base of the brain, responds by secreting two essential hormones ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH travels through the bloodstream to the Leydig cells within the testes, stimulating them to synthesize and release testosterone. FSH, conversely, targets the Sertoli cells, which are the supportive “nurse” cells within the seminiferous tubules where sperm development occurs. FSH is indispensable for initiating and maintaining spermatogenesis.

The testes, acting as the final component of this axis, produce both testosterone and sperm. Testosterone, while widely recognized for its role in male characteristics, also plays a direct, local role within the testes, supporting the maturation of sperm cells.

The entire system operates on a feedback loop, where rising levels of testosterone and inhibin (a hormone produced by Sertoli cells) signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, modulating GnRH, LH, and FSH release. This continuous dialogue ensures the body maintains a precise balance, adapting to internal and external cues.

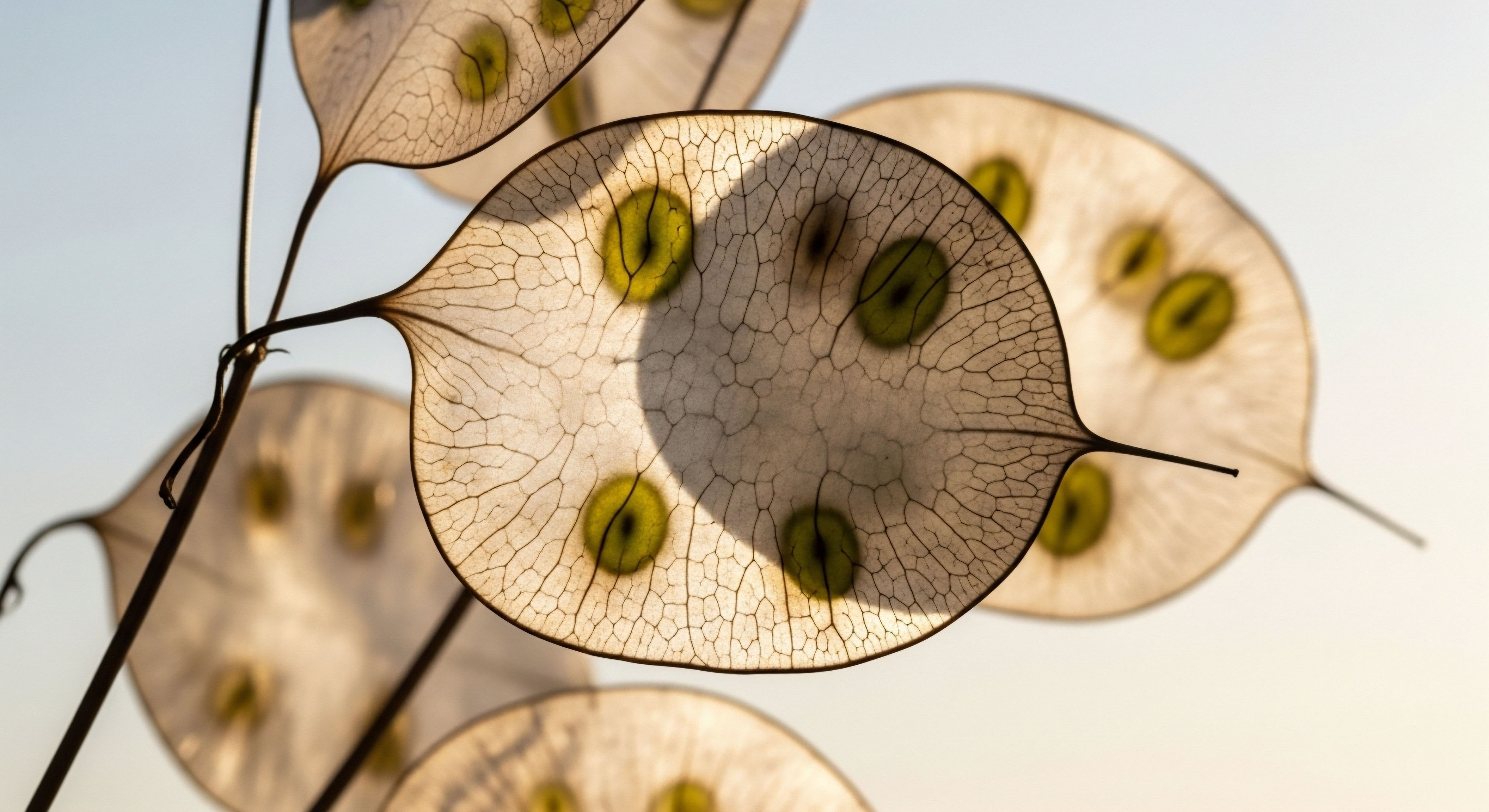

Spermatogenesis recovery involves a complex interplay of the HPG axis, where the hypothalamus, pituitary, and testes communicate through precise hormonal signals to restore sperm production.

Understanding this foundational biological framework provides a lens through which to view the factors influencing spermatogenesis recovery duration. It becomes clear that any disruption to this delicate hormonal dialogue, whether from external influences or internal imbalances, can extend the time required for the system to return to its functional baseline. The process demands patience and a targeted approach, aligning with the body’s inherent biological rhythms.

Intermediate

When considering the restoration of spermatogenesis, particularly after a period of exogenous testosterone administration or in cases of primary hypogonadism, specific clinical protocols become central to the discussion. These protocols aim to recalibrate the HPG axis, encouraging the body to resume its natural production of sperm. The interventions are designed to address the suppression that can occur when the body perceives sufficient testosterone from external sources, thereby reducing its own internal signaling for sperm creation.

One primary strategy involves the use of medications that directly stimulate the pituitary or block negative feedback signals. These agents work in concert to reawaken the dormant pathways responsible for testicular function. The goal is to provide the necessary biochemical cues for the testes to resume their critical role in reproductive health.

Targeted Agents for Spermatogenesis Support

Several pharmacological agents are employed in these recovery protocols, each with a distinct mechanism of action:

- Gonadorelin ∞ This synthetic analog of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) directly stimulates the pituitary gland to release LH and FSH. Administered typically via subcutaneous injections, often twice weekly, Gonadorelin mimics the natural pulsatile release of GnRH from the hypothalamus. This direct stimulation helps to restart the pituitary’s signaling to the testes, which is crucial for both testosterone production and spermatogenesis. Its use aims to prevent or reverse testicular atrophy and preserve fertility during or after testosterone replacement.

- Tamoxifen ∞ A selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), Tamoxifen works by blocking estrogen’s negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary. Estrogen, even in men, can signal to the brain that sufficient sex hormones are present, thereby suppressing LH and FSH release. By blocking these estrogen receptors, Tamoxifen effectively “removes the brake” from the HPG axis, allowing for increased secretion of LH and FSH, which in turn stimulates testicular function and sperm production.

- Clomid (Clomiphene Citrate) ∞ Similar to Tamoxifen, Clomid is also a SERM. It acts by competitively binding to estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary, preventing estrogen from exerting its inhibitory effects. This leads to an increase in GnRH, LH, and FSH secretion, thereby stimulating the Leydig cells to produce more endogenous testosterone and the Sertoli cells to support spermatogenesis. Clomid is often prescribed as an oral tablet, providing a convenient method for HPG axis stimulation.

- Anastrozole ∞ This medication is an aromatase inhibitor. Aromatase is an enzyme that converts androgens (like testosterone) into estrogens. By inhibiting this enzyme, Anastrozole reduces the overall estrogen levels in the body. Lower estrogen levels can reduce the negative feedback on the HPG axis, allowing for increased LH and FSH production. It is often included in protocols to manage potential estrogenic side effects from rising testosterone levels or to further enhance the HPG axis stimulation by reducing estrogenic suppression.

Clinical protocols for spermatogenesis recovery frequently involve Gonadorelin, Tamoxifen, Clomid, and Anastrozole, each designed to stimulate or modulate the HPG axis for renewed sperm production.

The specific combination and dosage of these agents are tailored to the individual’s unique physiological response and clinical objectives. Regular monitoring of hormone levels, including testosterone, LH, FSH, and estradiol, is essential to guide adjustments and ensure the protocol is effectively promoting recovery without adverse effects.

Comparing Spermatogenesis Recovery Agents

Understanding the distinct actions of these agents helps in appreciating their strategic deployment in recovery protocols.

| Agent | Primary Mechanism of Action | Targeted Effect on Spermatogenesis | Typical Administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gonadorelin | GnRH analog; direct pituitary stimulation | Directly stimulates LH/FSH release, promoting testicular function and sperm production | Subcutaneous injection, 2x/week |

| Tamoxifen | Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM) | Blocks estrogen negative feedback on pituitary/hypothalamus, increasing LH/FSH | Oral tablet |

| Clomid | Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM) | Blocks estrogen negative feedback on pituitary/hypothalamus, increasing LH/FSH | Oral tablet |

| Anastrozole | Aromatase Inhibitor | Reduces estrogen conversion, decreasing negative feedback on HPG axis | Oral tablet, 2x/week |

The duration of these protocols varies significantly among individuals, influenced by factors such as the duration of prior testosterone suppression, individual biological responsiveness, and overall metabolic health. A patient’s journey toward full spermatogenesis recovery is a highly personalized process, requiring consistent clinical oversight and patience.

Academic

The duration of spermatogenesis recovery extends beyond the simple application of stimulating agents; it is deeply intertwined with the intricate molecular and cellular dynamics of the male reproductive system, alongside broader metabolic and environmental influences. A comprehensive understanding requires a deep dive into the endocrinological nuances and the systems-biology perspective, recognizing that the testes do not operate in isolation but are influenced by the entire physiological landscape.

Molecular Signaling and Cellular Dynamics

Spermatogenesis is a highly organized process occurring within the seminiferous tubules of the testes, involving a precise sequence of cell divisions and differentiations. This process is critically dependent on the coordinated action of gonadotropins (LH and FSH) and local testicular factors.

Luteinizing Hormone (LH) primarily acts on the Leydig cells, which reside in the interstitial tissue between the seminiferous tubules. LH binding to its receptors on Leydig cells initiates a signaling cascade, primarily through the cyclic AMP (cAMP) pathway, leading to the synthesis of testosterone from cholesterol.

This locally produced testosterone is indispensable for spermatogenesis. While systemic testosterone levels are important, the high local concentration of testosterone within the seminiferous tubules, maintained by the androgen-binding protein produced by Sertoli cells, is particularly vital for germ cell development.

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), on the other hand, targets the Sertoli cells, which are the somatic cells within the seminiferous tubules that provide structural and nutritional support to developing germ cells. FSH binding to its receptors on Sertoli cells stimulates their proliferation and differentiation, as well as the production of various factors essential for spermatogenesis, including androgen-binding protein (ABP), inhibin B, and growth factors.

ABP maintains the high local testosterone concentration, while inhibin B provides negative feedback to the pituitary, regulating FSH secretion. The integrity and function of Sertoli cells are paramount for the progression of spermatogenesis, from spermatogonia to mature spermatozoa.

The pulsatile nature of GnRH release from the hypothalamus is a fundamental determinant of LH and FSH secretion. Disruptions to this pulsatility, often seen with continuous exogenous testosterone administration, can lead to significant suppression of endogenous gonadotropin release, thereby halting the natural testicular function. Recovery protocols aim to re-establish this pulsatile signaling, allowing the pituitary to resume its rhythmic communication with the testes.

Metabolic Health and Testicular Function

Beyond direct hormonal signaling, systemic metabolic health exerts a profound influence on spermatogenesis recovery duration. Conditions such as insulin resistance, obesity, and chronic inflammation can significantly impair testicular function and prolong recovery.

- Insulin Resistance ∞ This condition, characterized by the body’s reduced responsiveness to insulin, is frequently associated with lower testosterone levels and impaired sperm quality. Insulin resistance can directly affect Leydig cell function, reducing their capacity to produce testosterone. It also contributes to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which are detrimental to germ cell development and the integrity of the seminiferous tubules.

- Obesity ∞ Adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, is metabolically active and contains the aromatase enzyme, which converts androgens into estrogens. In individuals with excess adiposity, this increased aromatase activity leads to higher circulating estrogen levels. Elevated estrogen provides strong negative feedback to the HPG axis, suppressing LH and FSH release and consequently reducing endogenous testosterone production and impairing spermatogenesis. Weight management and body composition optimization are therefore critical components of a holistic recovery strategy.

- Systemic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress ∞ Chronic low-grade inflammation, often associated with metabolic dysfunction, can directly damage testicular tissue and germ cells. Inflammatory cytokines can disrupt the blood-testis barrier, a protective immunological barrier essential for spermatogenesis, and induce oxidative stress. Oxidative stress, an imbalance between reactive oxygen species production and antioxidant defenses, can lead to DNA damage in sperm, impairing their viability and function. Addressing underlying inflammatory drivers through nutritional interventions and lifestyle modifications can significantly support recovery.

Metabolic health, including insulin sensitivity, body composition, and inflammatory status, significantly influences spermatogenesis recovery by impacting hormonal balance and testicular cellular integrity.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

The modern environment presents numerous challenges to male reproductive health, and these factors can certainly extend the duration of spermatogenesis recovery. Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), found in plastics, pesticides, and personal care products, can interfere with hormonal signaling pathways, mimicking or blocking natural hormones. These disruptions can directly impair testicular function and the delicate balance of the HPG axis.

Lifestyle choices also play a critical role. Chronic psychological stress can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to increased cortisol production. Elevated cortisol levels can suppress GnRH release, thereby inhibiting LH and FSH secretion and impairing testicular function. Adequate sleep, balanced nutrition, and regular physical activity are not merely general wellness recommendations; they are fundamental pillars supporting optimal hormonal balance and cellular repair mechanisms necessary for spermatogenesis.

How Do Environmental Toxins Influence Spermatogenesis Recovery Duration?

Environmental toxins, particularly endocrine-disrupting chemicals, can directly interfere with the intricate hormonal signaling required for sperm production. These compounds can mimic or block the actions of natural hormones, leading to dysregulation of the HPG axis and direct damage to testicular cells.

The cumulative exposure to such chemicals can create a persistent challenge for the body’s ability to restore spermatogenesis, often prolonging the recovery period. Understanding these external influences allows for targeted mitigation strategies, such as reducing exposure to plastics and choosing organic produce, to support the body’s inherent healing capacities.

The duration of spermatogenesis recovery is thus a reflection of the body’s overall systemic health and its capacity for biological recalibration. It is a process that demands a comprehensive approach, addressing not only the direct hormonal signaling but also the broader metabolic, inflammatory, and environmental landscape. A patient’s journey toward restored fertility and vitality is a testament to the body’s remarkable ability to heal when provided with the right conditions and support.

References

- Handelsman, D. J. & Inder, W. J. (2013). Testosterone and the Male Reproductive System. In L. J. De Groot & G. M. Chrousos (Eds.), Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.

- Nieschlag, E. & Behre, H. M. (Eds.). (2012). Andrology ∞ Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction (3rd ed.). Springer.

- Sharpe, R. M. (2018). Hormonal control of spermatogenesis. In Encyclopedia of Reproduction (2nd ed. Vol. 3, pp. 297-304). Academic Press.

- McLachlan, R. I. & O’Donnell, L. (2019). Hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis and its disorders. In Endocrinology ∞ Adult and Pediatric (7th ed. Vol. 2, pp. 2005-2017). Elsevier.

- Kumanov, P. & Nandipati, K. C. (2017). Male Infertility and Endocrine Disorders. In Endocrine Disorders and Male Reproductive Health (pp. 1-22). Springer.

- Travison, T. G. et al. (2017). The relationship between obesity and testosterone in men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 102(11), 4067-4076.

- Santi, D. et al. (2018). Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Male Reproductive Health. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 9, 705.

- Foresta, C. et al. (2011). Insulin resistance and male reproduction. Human Reproduction Update, 17(5), 675-688.

Reflection

As you consider the intricate biological systems that govern male reproductive health, you might begin to perceive your own body not as a collection of isolated parts, but as a deeply interconnected network. The insights shared here, from the precise dance of the HPG axis to the pervasive influence of metabolic health and environmental factors, serve as a starting point.

This knowledge is not merely academic; it is a tool for introspection, prompting you to consider how your daily choices and broader environment might be influencing your internal equilibrium.

Understanding these mechanisms empowers you to engage more deeply with your own health journey. It suggests that reclaiming vitality and function is a collaborative effort between your inherent biological resilience and informed, personalized guidance. The path to optimal well-being is unique for each individual, requiring a thoughtful approach that respects your personal physiology and aspirations.