Fundamentals

Your journey toward understanding your body is profoundly personal. It begins with a feeling, a symptom, or a quiet sense that things are not as they should be. Perhaps it is a persistent fatigue that sleep does not touch, a shift in your mood that feels foreign, or changes in your physical self that you cannot explain.

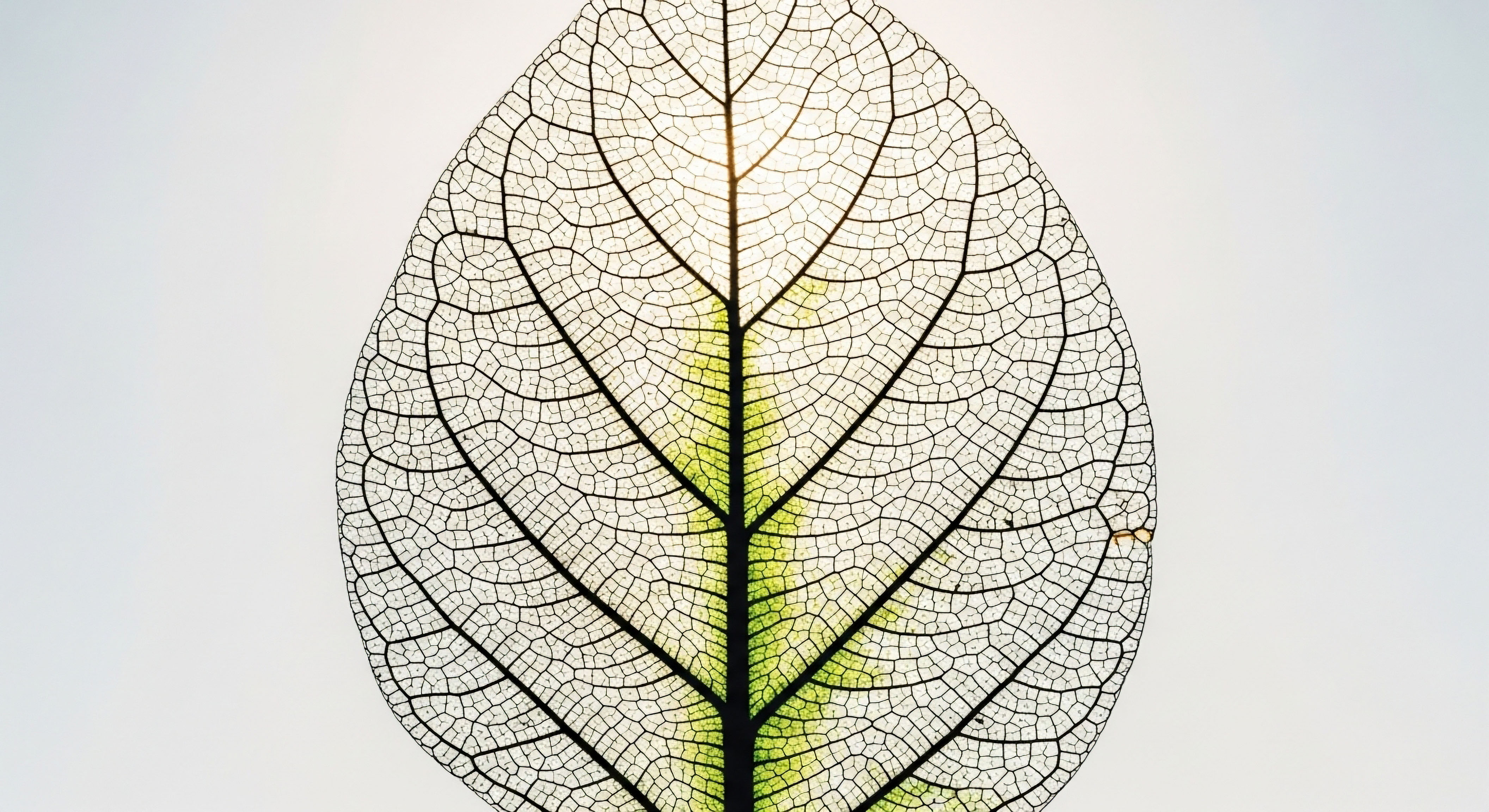

These experiences are the starting point. They are valid signals from your body’s intricate internal communication system, the endocrine network. When you decide to investigate these signals through hormonal testing, you are creating a map of this internal world. This map, composed of precise data points, reflects the core of your vitality, your emotional state, and your metabolic function. It is a biological blueprint of your present self.

This information is more than a set of numbers on a lab report. It is a narrative of your unique physiology. It details the activity of powerful chemical messengers that govern everything from your energy levels and stress response to your reproductive health and cognitive clarity.

Because this data is so intimately tied to who you are, the question of who has access to it, and for what purpose, becomes critically important. The moment this personal blueprint is digitized, it enters a vast and complex ecosystem. It becomes an asset, a commodity with significant commercial value. Understanding the ethical dimensions of this reality is the first step in reclaiming agency over your own health story.

Your hormonal data is a detailed narrative of your body’s inner workings, making its security and use a deeply personal issue.

What Is Personalized Hormone Data?

Personalized hormone data refers to the specific measurements of your body’s endocrine markers. This includes levels of key hormones such as testosterone, estrogen, progesterone, cortisol, thyroid hormones (T3, T4, TSH), and many others. When you engage with a clinical service for hormone optimization, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or peptide therapy, this data collection becomes even more granular.

It includes not just baseline levels, but also your body’s response to specific protocols, dosages, and adjunctive treatments like Anastrozole or Gonadorelin. This creates a longitudinal record, a moving picture of your biochemistry over time.

This dataset might contain the following layers of information:

- Core Biomarkers ∞ These are the fundamental measurements from blood, saliva, or urine tests. They provide a snapshot of your hormonal status at a specific moment.

- Phenotypic Data ∞ This is the collection of your expressed traits and symptoms. It is the story you tell your clinician about your fatigue, mood, libido, or physical performance. When this subjective experience is correlated with your objective biomarkers, the data becomes immensely powerful.

- Treatment Data ∞ This layer includes the specifics of your personalized protocol. It details the type of therapy (e.g. Testosterone Cypionate injections, Ipamorelin peptides), the dosage, the frequency, and your physiological response.

- Genetic Information ∞ With the rise of direct-to-consumer genetic testing, many individuals now possess a fourth layer of data. Your genetic predispositions, when combined with your hormonal profile, can offer predictive insights into your health trajectory and your potential response to certain therapies.

This multi-layered dataset is a uniquely sensitive and valuable asset. It reveals not just your current health status, but also provides a basis for predicting future health outcomes and your potential as a consumer of health products. The commercialization of this data involves packaging and selling these insights to third parties who see its potential for profit.

The Commercial Value of Your Biological Blueprint

In the digital economy, data is a currency. Health data, and particularly the rich, longitudinal data from personalized wellness protocols, is one of the most valuable forms of this currency. Companies in various sectors are willing to pay for access to this information because it allows them to build highly accurate consumer profiles and predictive models. The process begins with the collection of your information, often through direct-to-consumer testing companies, wellness apps, or digital health platforms.

Your data is often “de-identified,” a process where direct identifiers like your name and address are removed. The data is then aggregated with data from thousands of other individuals, creating large datasets that can be analyzed for trends. For-profit companies are interested in these datasets for several reasons:

- Pharmaceutical Research and Development ∞ A pharmaceutical company can analyze aggregated hormonal data to identify populations that might benefit from a new drug. For instance, data showing a high prevalence of specific hormonal imbalances in a certain demographic could guide the development and marketing of a new therapeutic.

- Targeted Advertising ∞ Data brokers and marketing firms purchase these datasets to create detailed consumer profiles. If your data indicates you are a man undergoing TRT, you might be targeted with advertisements for specific supplements, gym memberships, or related health services. This targeting can be incredibly specific and effective.

- Insurance and Financial Industries ∞ While regulations like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in the United States offer some protections, the potential for health data to be used in risk assessment models by insurance companies remains a significant concern. Aggregated data can be used to assess the health risks of entire populations, which can indirectly affect policy pricing and availability.

- Corporate Wellness and Technology ∞ Tech companies developing new health-tracking wearables, apps, or AI-driven diagnostic tools need vast amounts of data to train their algorithms. Your personalized hormone data is the raw material that fuels the next generation of health technology.

The core ethical dilemma arises from a fundamental disconnect. You provide your biological samples and personal information with the goal of improving your own health. You are seeking clarity and a path toward feeling better. The companies facilitating this process, however, may have a dual purpose.

They provide a service to you while also viewing your data as a revenue-generating asset to be packaged and sold. This commercial interest can exist in direct tension with your right to privacy and your desire to control your own personal health narrative. The validation of your lived experience must be paired with a clear-eyed understanding of the systems that seek to monetize it.

Intermediate

The journey of your personalized hormone data from a blood sample to a line item on a data broker’s spreadsheet is a complex process governed by a patchwork of regulations and corporate policies. Understanding this lifecycle is essential for anyone engaging in personalized wellness protocols.

The moment you consent to a service, you are initiating a chain of events that extends far beyond your clinician’s office. The ethical considerations at this level move from the abstract to the practical, focusing on the mechanics of data flow, the limitations of privacy protections, and the nature of informed consent in the digital age.

The Lifecycle of Personalized Health Data

The commercialization of your hormone data is not a single event, but a multi-stage process. Each step presents unique ethical questions and potential vulnerabilities. Let’s trace the typical path of this information.

- Collection and Consent ∞ The process begins when you sign up for a service, whether it’s a direct-to-consumer hormone test or a comprehensive clinical protocol like TRT or peptide therapy. At this stage, you are presented with a privacy policy and terms of service. These documents, often lengthy and filled with legal jargon, outline how your data will be used. A key ethical issue here is the quality of “informed consent.” Many individuals agree to these terms without fully comprehending that they may be authorizing the company to de-identify and sell their data for research or commercial purposes.

- Analysis and Aggregation ∞ Your biological sample is analyzed, and the results are combined with the personal and symptomatic information you provided. This creates your individual dataset. The company then aggregates your de-identified data with that of thousands of other users. This aggregation is a critical step; it transforms individual data points into a statistically significant and commercially valuable dataset.

- De-Identification and Its Limits ∞ To comply with privacy regulations like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), companies must “de-identify” the data before sharing or selling it. This involves removing a specific list of 18 identifiers, including name, address, and social security number. The persistent ethical challenge is that de-identification is not foolproof. With the addition of other publicly available datasets (e.g. voter registrations, social media information), it is possible to “re-identify” individuals from an anonymized dataset. The more unique your health profile and demographic data, the higher the risk of re-identification.

- Sale and Distribution ∞ The aggregated, de-identified dataset is then licensed or sold to third parties. These can include pharmaceutical companies, academic researchers, marketing firms, and other tech companies. The initial company profits from this sale, creating a powerful financial incentive to maximize data collection.

- Third-Party Use ∞ The purchasing entity now uses your data for its own purposes. A pharmaceutical company might use it to identify a target market for a new drug that modulates estrogen. A marketing firm could use it to create a “lookalike audience” of individuals with similar health profiles to target with specific ads. The use of your data at this stage is far removed from your original intent of seeking personal health insights.

What Makes Hormonal Data Uniquely Sensitive?

All health data is sensitive, but personalized hormonal data carries a unique weight. It provides a window into the very core of an individual’s being, revealing information that is often deeply private and potentially stigmatizing. Commercializing this specific type of data raises distinct ethical alarms.

- Reproductive Health and Fertility ∞ Hormonal profiles can reveal information about a woman’s menopausal status, her fertility potential, or conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). For men, data from TRT protocols combined with Gonadorelin use can indicate attempts to preserve or restore fertility. The commercial use of this data could lead to targeted marketing for fertility treatments or, more troublingly, potential discrimination.

- Mental and Emotional State ∞ Hormones like cortisol, thyroid hormones, and sex hormones have a profound impact on mood, anxiety, and cognitive function. A dataset that shows a correlation between low testosterone and reported symptoms of depression is a powerful tool for companies marketing antidepressants or mental wellness apps.

- Aging and Vitality ∞ Protocols involving Growth Hormone peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin are explicitly aimed at mitigating aspects of the aging process. Data from these protocols provides a direct signal of an individual’s concerns about aging, making them a prime target for a vast range of “anti-aging” products and services.

- Lifestyle and Behavior ∞ Hormonal data can indirectly reveal lifestyle choices. For example, patterns in cortisol levels might suggest high stress, while certain hormonal markers can be affected by diet, exercise, and sleep patterns. This information can be used to build a behavioral profile that is highly valuable to marketers.

The process of de-identifying health data is not infallible, and the potential for re-identification poses a persistent risk to individual privacy.

The commercialization of this data means that these deeply personal aspects of your life can be translated into attributes within a marketing profile, shaping the digital world you experience and the commercial messages you receive.

Navigating a Complex Regulatory Landscape

The rules governing the use of health data are complex and vary by jurisdiction. In the United States, the primary framework is HIPAA. However, HIPAA’s protections have significant limitations in the context of modern data commercialization.

The table below provides a simplified comparison of two key regulatory frameworks:

| Feature | HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) – USA | GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) – EU |

|---|---|---|

| Who is Covered? | Applies to “covered entities” (healthcare providers, health plans, healthcare clearinghouses) and their “business associates.” It does not typically cover direct-to-consumer companies, wellness apps, or genetic testing companies that are not affiliated with a covered entity. | Applies to any organization that processes the personal data of individuals residing in the European Union, regardless of where the organization is based. This has a much broader reach. |

| Definition of Personal Data | Focuses on “Protected Health Information” (PHI), which is health data created or received by a covered entity that can be linked to a specific individual. | Defines “personal data” very broadly to include any information relating to an identifiable person, including genetic and biometric data. The standard for identifiability is high. |

| Consent | Allows for the use and disclosure of de-identified data without patient consent. The standards for de-identification are defined within the law. | Requires explicit, unambiguous consent for each specific purpose of data processing. “Blanket consent” for future, unspecified uses is generally not permissible. Individuals have a clear right to withdraw consent. |

| Data Portability | Provides a right for individuals to access and receive a copy of their PHI from covered entities. | Provides a right for individuals to receive their personal data in a machine-readable format and to transmit that data to another controller. This is a more powerful right of control. |

| Right to Erasure | Does not provide a general “right to be forgotten.” Data is retained according to legal and professional standards. | Includes a “right to erasure” (the “right to be forgotten”), allowing individuals to request the deletion of their personal data under certain circumstances. |

This comparison highlights a critical ethical gap. Many of the companies at the forefront of personalized wellness and data commercialization operate outside the direct purview of HIPAA. They collect your hormonal data, your genetic data, and your lifestyle information, and because they are not your direct healthcare provider in the traditional sense, they may operate in a regulatory gray area.

This leaves the consumer in a vulnerable position, often with fewer rights and protections than they assume. A responsible approach to personalized wellness requires a clear understanding of these limitations and a commitment to advocating for stronger, more comprehensive data privacy laws that reflect the realities of the 21st-century health landscape.

Academic

The commercialization of personalized hormone data represents a new frontier in bioethics, one that moves beyond traditional discussions of patient confidentiality into the complex domain of predictive analytics, biocapital, and the algorithmic construction of identity. At an academic level, the most pressing ethical considerations arise at the intersection of longitudinal endocrine data and pharmacogenomics.

This convergence creates a dataset of unprecedented power, capable of generating novel therapeutic insights while simultaneously posing profound risks of genetic discrimination, population-level surveillance, and the erosion of individual autonomy. A rigorous examination of this issue requires a systems-biology perspective, viewing the data not as isolated markers but as a dynamic representation of the interplay between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, metabolic pathways, and an individual’s unique genetic blueprint.

The Synergistic Power of Hormonal and Genomic Datasets

The true value for commercial entities lies in the fusion of two distinct but deeply interconnected streams of biological information ∞ the dynamic, real-time functionality of the endocrine system and the static, predictive potential of the genome. When a company acquires both your hormonal panel from a TRT protocol and your raw genetic data from a direct-to-consumer (DTC) testing service, it can create a multi-dimensional profile that is vastly more valuable than the sum of its parts.

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how an individual’s genes affect their response to drugs. Historically, this has been used to predict adverse reactions or to optimize dosing for specific medications. When applied to hormonal health, it opens up new possibilities. For example, variations in genes like CYP19A1 can influence the rate at which testosterone is converted to estrogen.

An individual with a specific polymorphism in this gene might require a different dose of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to manage side effects during TRT. This is a clinically valuable insight.

However, when these datasets are aggregated on a massive scale, the focus shifts from individual clinical management to population-level predictive modeling. A commercial entity can now ask far more complex questions:

- Predictive Efficacy ∞ Can we identify genetic markers that predict which individuals will have the most robust response to a specific growth hormone peptide, like Tesamorelin, for visceral fat reduction? This allows for the targeted marketing of that peptide to a pre-qualified audience.

- Risk Stratification ∞ Are there genetic variants that, when combined with a specific hormonal profile (e.g. low testosterone and high cortisol), correlate with a higher long-term risk for metabolic syndrome or cardiovascular disease? This information is of immense interest to insurance companies and public health planners, but it also creates a framework for potential discrimination.

- Novel Drug Discovery ∞ By analyzing the complex interplay between genes, hormone levels, and patient-reported outcomes, companies can identify new biological pathways to target for drug development. The aggregated data of thousands of individuals on personalized protocols becomes the unpaid, and often unwitting, foundation for the next generation of patented pharmaceuticals.

This process transforms the individual’s health journey into a form of “biocapital.” Your biology, digitized and aggregated, becomes a raw material that generates economic value for corporations. The ethical dilemma is that the individual who provides this raw material rarely shares in the immense profits generated from it and may be exposed to new forms of risk without their explicit and fully informed consent.

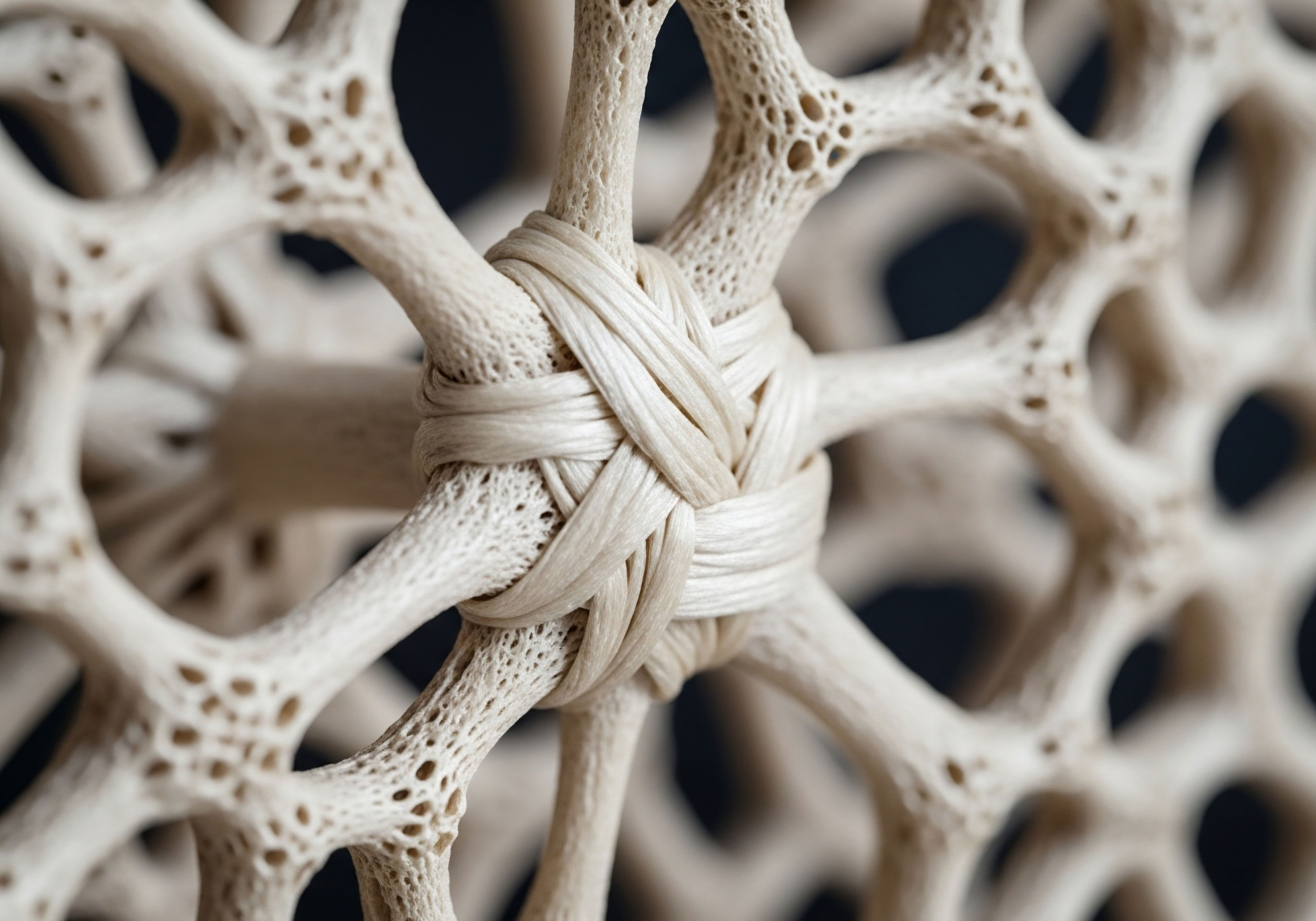

What Are the Limits of Anonymization in High-Dimensional Data?

The standard defense against privacy concerns is the practice of data anonymization or de-identification. However, in the context of high-dimensional datasets that include both genomic and longitudinal hormonal data, the concept of true anonymization becomes fragile, if not entirely illusory. Research has repeatedly shown that individuals can be re-identified from anonymized datasets using only a small number of data points.

Consider the following table, which details the types of data points that might be collected in a comprehensive, personalized wellness program. The combination of these factors creates a unique signature that can defy conventional de-identification techniques.

| Data Category | Specific Data Points | Potential for Re-identification and Commercial Use |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age (or birth year), ZIP code, ethnicity | When combined with other data, these points can be cross-referenced with public records to narrow down identity. ZIP code plus birth date can uniquely identify a significant portion of the population. |

| Genomic Data | Raw SNP data, specific gene variants (e.g. APOE, MTHFR), ancestry information | Genomic data is a uniquely powerful identifier. Even a small subset of SNPs can be used to link an “anonymous” sample to a named individual in a public genealogy database. |

| Endocrine Data | Longitudinal levels of Testosterone, Estradiol, SHBG, LH, FSH, Cortisol, DHEA-S, TSH | The specific trajectory of multiple hormone levels over time creates a unique “hormonal fingerprint.” This is especially true when it reflects a response to a specific therapeutic protocol. |

| Pharmacological Data | Specific protocol used (e.g. Testosterone Cypionate 150mg/week + Anastrozole 0.25mg 2x/week + Ipamorelin 300mcg/day) | Highly specific treatment regimens are not common. This information, combined with a general location and age, can act as a powerful quasi-identifier. |

| Phenotypic Data | Patient-reported symptoms (e.g. low libido, brain fog, joint pain), treatment goals (e.g. muscle gain, fat loss) | This narrative data adds another layer of specificity that can aid in re-identification and is extremely valuable for creating targeted marketing personas. |

The convergence of these data streams creates a situation where the promise of anonymity is a technical fiction. The ethical framework for data governance must evolve to acknowledge this reality. It must move beyond a focus on removing direct identifiers and toward a model that grants individuals fundamental rights over the use of their biological information, regardless of its “identifiable” state.

The fusion of genomic and longitudinal hormonal data creates a powerful predictive tool, raising complex ethical questions about biological privacy and data ownership.

Data Ownership and the Problem of Derived Insights

Who owns your personalized hormone data? The answer is legally and ethically ambiguous. You own your body, but do you own the data generated from it? When you provide a sample to a company, the terms of service often grant that company broad rights to use the resulting data. This raises an even more complex question ∞ who owns the insights derived from your data?

When your data is aggregated with thousands of others and analyzed using proprietary algorithms, new information is created. The algorithm might identify a novel correlation between a specific genetic marker and a positive response to a peptide like PT-141 for sexual health. This derived insight is a new piece of intellectual property.

It was created using your data, but it is owned by the company that performed the analysis. This is the core of the business model for many digital health companies.

This model raises several profound ethical issues:

- Equity and Justice ∞ The value generated by these derived insights is not shared with the individuals who provided the foundational data. This creates a system where the biological resources of the many are used to generate profits for the few. There is a growing argument for new models of “data trusts” or “information fiduciaries” that would manage personal data on behalf of individuals and ensure they share in the economic benefits.

- Transparency and Accountability ∞ The algorithms used to generate these insights are often “black boxes.” They are proprietary and opaque. An individual may be subject to decisions based on these algorithmic insights (e.g. being placed in a high-risk category for insurance) without any ability to understand, contest, or correct the underlying data or logic.

- Autonomy and Control ∞ The commercialization of derived insights creates a future where your biological data could be used to influence your choices and behaviors in ways you cannot anticipate. Predictive models could be used to target you with “interventions” designed to modify your behavior for commercial gain, all based on a profile that you did not explicitly create and do not control.

The ethical considerations that arise from the commercialization of personalized hormone data require a fundamental rethinking of our approach to privacy, ownership, and consent. The existing regulatory frameworks, developed in an era of siloed, paper-based records, are insufficient to address the challenges of a deeply interconnected, algorithmically-driven health economy.

As we continue to map the intricacies of the human endocrine system and genome, we must simultaneously develop a robust ethical and legal architecture that protects the individual at the center of this new biological frontier. This architecture must be built on the principles of transparency, equity, and the unwavering right of the individual to be the ultimate arbiter of their own biological narrative.

References

- Vayena, E. Gasser, U. & de Lombaerde, P. (Eds.). (2016). Big Data, Big Implications ∞ A Guide to the New Digital Public Health. United Nations University.

- Rothstein, M. A. & Knoppers, B. M. (2019). The new world of genetic and genomic data sharing. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 47(1), 5-6.

- Shabani, M. & Marelli, L. (2019). Emerging ethical issues regarding digital health data. On the World Medical Association Draft Declaration on Ethical Considerations Regarding Health Databases and Biobanks. Journal of Medical Ethics, 45(6), 411 ∞ 414.

- Evans, B. J. (2011). The limitless scope of the health information privacy laws. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 39(1), 5-7.

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics. (2015). The collection, linking and use of data in biomedical research and health care ∞ ethical issues. Nuffield Council on Bioethics.

- The Endocrine Society. (2022). Enhancing the Trustworthiness of the Endocrine Society’s Clinical Practice Guidelines. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 107(8), 2129 ∞ 2138.

- McGuire, A. L. & Beskow, L. M. (2010). Informed consent in genomics and genetic research. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 11, 361-381.

- Clayton, E. W. Evans, B. J. Hazel, J. W. & Rothstein, M. A. (2019). The law of genetic privacy ∞ applications, implications, and limitations. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 47(S3), 17-29.

- Mittelstadt, B. D. & Floridi, L. (2016). The ethics of big data ∞ Current and foreseeable issues in biomedical contexts. Science and engineering ethics, 22(2), 303-341.

- Issa, A. M. (2009). Ethical perspectives on pharmacogenomic profiling in the community. Personalized Medicine, 6(4), 403-413.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Course

The knowledge you have gained about your own biology and the digital world it inhabits is a form of power. It is the power to ask better questions, to make more informed choices, and to engage with your health journey from a position of strength.

The path to vitality is a personal one, and you are its primary navigator. The data, the protocols, and the clinical guidance are all tools to help you chart your course. They provide the coordinates and the topographical details, but you hold the compass. Your lived experience, your personal goals, and your intuitive sense of your own body are the ultimate arbiters of your direction.

Consider the information presented here not as a final destination, but as a set of navigational aids. The landscape of personalized medicine and digital health is constantly evolving. Your role is to remain an active, engaged, and curious participant in your own wellness.

Use this understanding to build a partnership with your clinical team, one founded on transparency and shared goals. Ask about their data privacy practices. Inquire about how your information is stored and used.

Your proactive engagement is the most crucial element in ensuring that your journey toward health is one that honors your autonomy, respects your privacy, and ultimately leads you to a place of greater function and well-being. The potential to recalibrate your biological systems and reclaim your vitality is immense. Let this knowledge be the foundation upon which you build your personal path forward.

Glossary

testosterone replacement therapy

personalized hormone data

when combined with

personalized wellness

digital health

hormonal data

health data

your personalized hormone data

your personalized hormone

ethical considerations

informed consent

hormone data

peptide therapy

re-identification

hipaa

data commercialization

pharmacogenomics

biocapital

data anonymization