Fundamentals

You have arrived at this point in your health journey because you are seeking a higher level of function. You feel the subtle, or perhaps pronounced, shifts in your body’s internal symphony ∞ the fatigue, the metabolic resistance, the loss of vitality ∞ and you recognize that the standard answers are insufficient.

Your search for tools like therapeutic peptides is a testament to your proactive stance, a desire to reclaim the biological inheritance of strength and clarity. It is within this very personal and driven pursuit that you encounter a landscape of immense promise shadowed by an equally immense ambiguity. The presence of impure, unregulated peptide products stems from a fundamental disconnect between the intended purpose of these molecules and the way they are being made available.

The primary mechanism allowing this situation to persist is a specific regulatory classification. Many of these compounds are distributed under the label “For Research Use Only” (RUO). This designation places them in a category akin to chemicals sold between scientific laboratories.

It signals that the product is intended for in-vitro experiments or animal studies, a context where the stringent requirements for human pharmaceuticals do not apply. This RUO pathway creates a parallel market that operates outside the direct oversight of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) framework for human drugs.

The system presumes a sophisticated end-user, a scientist who understands the product’s experimental nature. When these compounds are sought for personal wellness, a collision of two worlds occurs ∞ the world of clinical therapeutics and the world of unregulated chemical supply.

The “Research Use Only” label is the central regulatory gap that permits the distribution of peptides without clinical-grade purity verification.

The Two Paths of a Molecule

To understand this divide, consider the journey of a molecule intended for human use versus one intended for a research lab. An FDA-approved medication undergoes a rigorous, multi-year process of development, testing, and validation. Its manufacturing must adhere to a strict set of quality standards known as Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP).

Every step, from the sourcing of raw materials to the sterility of the final vial, is documented and validated to ensure safety, purity, and potency. This is a system built entirely around protecting the end user ∞ the patient.

The RUO peptide follows a different trajectory. Its synthesis may occur in a facility that does not operate under cGMP guidelines. The supply chain can be opaque, with little to no transparency about where the base ingredients originated or how they were handled.

The final product may lack the comprehensive testing that confirms its identity, purity, and the absence of harmful contaminants. The regulatory gap is this very divergence in pathways. One path is a meticulously paved and guarded highway designed for public transport. The other is an unmonitored service road intended for industrial use, which individuals are increasingly using as a shortcut to their destination of wellness, accepting the inherent and often invisible risks of the terrain.

What Defines a Therapeutic Tool?

The core of the issue rests on a question of definition. Is a peptide a therapeutic agent or a research chemical? The answer, from a regulatory standpoint, depends entirely on its label and intended use. The molecules themselves possess the potential to interact with human physiology in profound ways, acting as precise keys to unlock specific biological responses.

This inherent power is what makes them so compelling. The regulatory framework, however, responds to the manufacturer’s stated intent. By designating a product as RUO, a supplier effectively declares it is not for human application, thus navigating around the entire infrastructure of pharmaceutical safety. This leaves the ultimate responsibility, and the entire burden of risk, on the individual seeking to use these powerful tools for their own biological recalibration.

Intermediate

Advancing our understanding requires a closer examination of the specific mechanisms and agencies involved. The distribution of impure peptides is a direct consequence of an enforcement landscape struggling to keep pace with a rapidly evolving market. The FDA’s primary focus has historically been on drugs explicitly marketed for human use.

The “Research Use Only” designation creates a gray area where jurisdiction is less clear, allowing a market to flourish with minimal direct oversight of the products themselves. This has compelled a shift in regulatory strategy, moving from a focus on marketing language to a deeper scrutiny of the manufacturing and supply chain itself.

Regulators are increasingly targeting the source of these peptides. This includes unregistered manufacturing facilities and contract manufacturers who fail to provide documentation of cGMP, traceability, and sterile production standards. When a facility cannot demonstrate control over its processes, from the purity of its raw materials to the sterility of its final product, the potential for contamination or incorrect dosage becomes a significant public health concern.

The FDA views this lack of transparency as a critical failure, especially when these products are linked to websites or platforms that imply human application, directly contradicting the RUO disclaimer.

How Does the Regulatory Framework Miss the Mark?

The challenge for regulators is amplified by disparities in how existing guidelines are interpreted and applied. Guidelines from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), for instance, provide a framework for drug development, but their application to novel synthetic peptides can be inconsistent. This ambiguity creates difficulties for both ethical developers and the agencies tasked with oversight.

The result is a fractured landscape where some actors operate with high standards while others exploit the lack of clear, universally enforced rules for these specific molecules.

The table below illustrates the stark contrast between the two pathways. The journey of an FDA-approved therapeutic is defined by checkpoints and validation, while the RUO pathway is characterized by their absence.

| Development Stage | FDA-Approved Pharmaceutical Pathway | “Research Use Only” (RUO) Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Standards |

Strict adherence to Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) is mandatory. Facilities are regularly inspected by the FDA. |

No cGMP requirement. Manufacturing conditions are unknown and undocumented. |

| Purity & Identity Testing |

Each batch is rigorously tested for identity, purity, potency, and contaminants. Results must meet pre-defined specifications. |

Third-party testing may be claimed but is often unverified. Batch-to-batch consistency is not guaranteed. |

| Supply Chain |

Transparent and traceable from raw material to final product. All suppliers must be vetted and qualified. |

Often opaque. The origin of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and other components is frequently unknown. |

| Clinical Trials |

Extensive multi-phase human clinical trials are required to establish safety and efficacy. |

No human clinical trials are conducted. The product is not intended for human use. |

| Regulatory Submission |

A comprehensive data package is submitted to the FDA for review and approval before marketing. |

No submission to the FDA is required. The product is sold as a chemical, not a drug. |

The Role of Compounding Pharmacies

Compounding pharmacies represent another layer of complexity in this system. These pharmacies are licensed to prepare personalized medications for specific patients based on a prescription. While they serve a legitimate and important function in medicine, the space has been penetrated by entities engaging in large-scale production of peptide formulas without individual prescriptions.

This practice, known as mass compounding, is illegal and circumvents the FDA’s drug approval process. The FDA has issued numerous warning letters to such establishments. Compounded drugs are not FDA-approved, meaning they have not undergone the same rigorous testing for safety and efficacy. While potentially of higher quality than an RUO product from an unknown lab, they still carry risks and exist within a separate regulatory space from fully approved pharmaceuticals.

The absence of mandatory cGMP adherence and a transparent supply chain in the RUO market is the critical failure point allowing impure products to reach consumers.

Academic

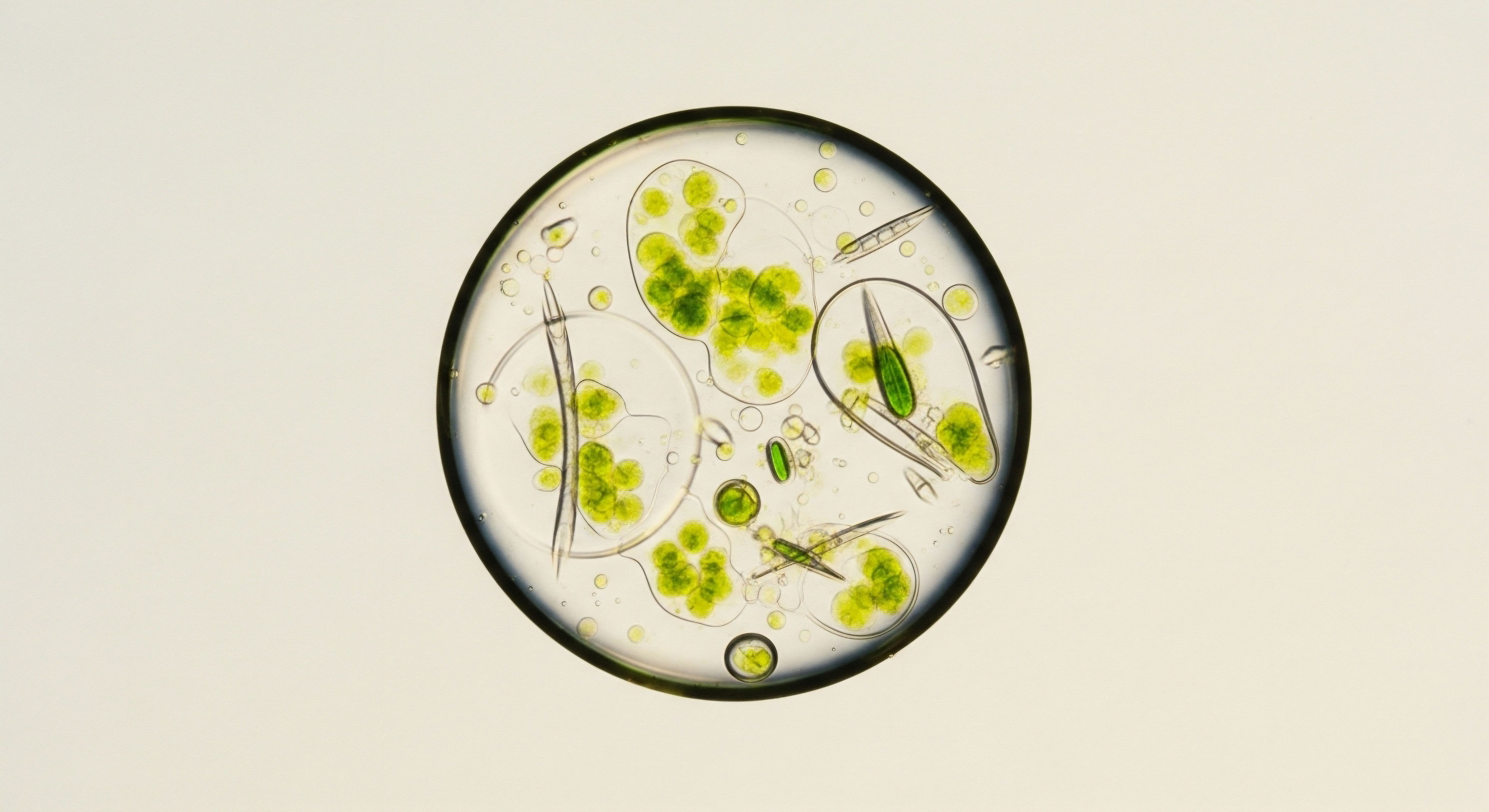

A granular analysis of the regulatory environment reveals that the challenges are rooted in the biochemical complexity of peptides and the legal definitions within existing statutes. Peptides are larger and more intricate than traditional small-molecule drugs, making the identification and characterization of impurities a far more demanding analytical task.

An impurity in a small-molecule drug might be a single, easily identifiable related compound. In a peptide synthesized via solid-phase methods, impurities can include a vast array of structurally similar but functionally distinct molecules. This biochemical reality complicates the application of established regulatory standards.

The FDA has acknowledged this complexity by issuing new guidance for certain highly purified synthetic peptide drug products. This guidance lowers the threshold for when an impurity must be scrutinized. For these peptides, any impurity present at a level above 0.10% that is not found in the reference drug must be evaluated for its potential to provoke an immune response (immunogenicity).

This is a stricter standard than the 0.15% threshold for many small-molecule drugs. This move signals a deeper appreciation of the risks associated with peptide impurities. A seemingly minor structural change can, in some cases, transform a therapeutic molecule into an antigenic one, capable of triggering an adverse immune reaction. The existence of this new, stricter guidance for approved products simultaneously highlights the profound lack of any such standard in the RUO market.

What Are the Specific Classes of Peptide Impurities?

The physiological risk of impure peptides stems from the diverse nature of the contaminants that can arise during synthesis and storage. These are not benign fillers; they are often structurally related molecules with the potential for unintended biological activity. Understanding these impurity classes is essential to appreciating the scale of the problem.

- Synthesis-Related Impurities ∞ These are errors that occur during the chemical construction of the peptide chain. They include deletions (a missing amino acid), insertions (an extra amino acid), or truncations (an incomplete peptide sequence). Such impurities can have altered or no biological activity, or they could potentially bind to the wrong receptor, causing off-target effects.

- Deprotection-Related Impurities ∞ The chemical groups used to protect amino acids during synthesis must be completely removed in the final step. Incomplete deprotection can leave residual chemical modifications on the peptide, altering its structure, charge, and function, which can directly impact its interaction with physiological systems.

- Reagent-Related Impurities ∞ These are residual chemicals from the synthesis process itself. Solvents, coupling agents, and other reagents, if not completely removed, can be toxic or cause adverse reactions.

- Degradation Products ∞ Peptides can break down over time due to factors like temperature, pH, or oxidation. This degradation creates new molecular species, reducing the potency of the product and introducing new, unknown compounds into the system.

Peptide impurities are not merely inert substances; they are structurally distinct molecules capable of unpredictable and potentially disruptive biological activity.

The table below provides a more detailed view of these impurities and their potential clinical significance, illustrating the direct link between manufacturing quality and physiological safety.

| Impurity Class | Description | Potential Physiological Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Variants |

Peptides with one or more amino acids that are incorrect, omitted, or added to the intended sequence. |

Can act as a competitive antagonist at the target receptor, reducing efficacy. May also possess agonist activity at other receptors, causing off-target effects or an immunogenic response. |

| Truncated/Extended Forms |

Peptide chains that are shorter or longer than the intended molecule. |

Typically results in a loss of potency. In some cases, fragments can interfere with the intended biological pathway. |

| Oxidation Products |

Specific amino acids (like methionine or tryptophan) are susceptible to oxidation, altering the peptide’s structure. |

Can lead to a significant reduction or complete loss of biological activity. The oxidized form may be recognized as foreign by the immune system. |

| Aggregates |

Peptide molecules clumping together to form larger complexes. |

Can significantly increase the risk of an immunogenic reaction. Aggregates can also reduce the bioavailability and efficacy of the product. |

This deep biochemical risk is at the heart of the regulatory gap. The legal framework of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was built around a clear distinction between chemicals for research and drugs for therapy. The rise of a consumer market for products labeled for research exploits this distinction.

The law is not silent, but it is slow to adapt. Enforcement actions are increasing, but they are chasing a decentralized and agile market. The ultimate regulatory gap is the space between the letter of the law, the pace of enforcement, and the speed at which these powerful biological tools are being distributed without the scientific guardrails designed to ensure they heal rather than harm.

References

- Cohen, Jeff, and Caitlin A. Koppenhaver. “The FDA Is Expanding Its Oversight ∞ Research Use Only Peptide Businesses Should Be Watching Manufacturing Closely.” Florida Healthcare Law Firm, 2024.

- Vippagunta, Sudha, et al. “Development and Regulatory Challenges for Peptide Therapeutics.” International Journal of Toxicology, vol. 40, no. 1, 2021, pp. 16-25, DOI ∞ 10.1177/1091581820977846.

- Teva API. “Challenges in the Changing Peptide Regulatory Landscape.” TAPI, 28 Nov. 2022.

- Ahamad, Afzal, et al. “Regulatory Guidelines for the Analysis of Therapeutic Peptides and Proteins.” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 4, 2024, p. 1493, DOI ∞ 10.3390/app14041493.

- “Protect yourself from counterfeit and unsafe, mass compounded products.” Eli Lilly and Company, 2025.

Reflection

The Final Step in the Protocol Is Discernment

You began this inquiry seeking to understand the systems that govern the tools of your own potential optimization. The knowledge of these regulatory fissures and manufacturing deficits is now part of your toolkit. It provides a new lens through which to view the landscape of personalized wellness.

The path toward reclaiming your vitality is paved with precise biological information ∞ in your labs, in your body’s feedback, and now, in your comprehension of the very substances you might consider using. This understanding moves you from a position of passive hope to one of active and informed decision-making.

The ultimate protocol is one that synthesizes molecular science with profound self-awareness, ensuring that every step taken is one of genuine, validated progress. Your journey is your own; its safety and efficacy are reflections of the questions you ask before you begin.

Glossary

research use only

drug

current good manufacturing practices

regulatory gap

good manufacturing practices

compounding pharmacies

immunogenicity

peptide impurities

biological activity

and cosmetic act