Fundamentals

Embarking on a wellness program is a profound act of self-investment. You are choosing to engage with your own biology, to understand the intricate signals your body sends, and to reclaim a sense of vitality. This journey, however, brings with it a critical question ∞ what happens to the deeply personal health data you generate?

The information from your hormone panels, metabolic tests, and biometric screenings constitutes a unique biological signature. Understanding the protections afforded to this data is as foundational as understanding the therapies themselves. The primary architecture of health data protection in the United States is the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

This federal law establishes a national standard for safeguarding medical information, which it defines as Protected Health Information (PHI). PHI includes any identifiable health data held by specific entities. The entities bound by HIPAA’s stringent rules are known as “covered entities,” which are principally health plans, health care providers, and health care clearinghouses.

The applicability of HIPAA to your wellness program hinges entirely on its structure. Many wellness initiatives are offered as a component of an employer-sponsored group health plan. In this arrangement, the wellness program functions as an extension of your health plan.

Consequently, the data you provide, from blood work detailing testosterone levels to questionnaires about metabolic symptoms, is considered PHI and receives the full force of HIPAA’s privacy and security protections. The group health plan is the covered entity, and it carries the legal responsibility for ensuring your data is not used or disclosed improperly. Your employer, in this context, may have access to some of this information for administrative purposes, but that access is strictly regulated.

A different scenario unfolds when a wellness program is offered directly by an employer, independent of any group health plan. In this case, the health information collected is not automatically classified as PHI under HIPAA. This creates a significant distinction in the level of federal privacy protection.

While other federal or state laws may apply, the specific, rigorous framework of HIPAA does not. This structural nuance is vital to comprehend. Your participation in a biometric screening or a health coaching session may generate the same type of sensitive data, but the legal shield protecting it can differ substantially based on whether the program is an integrated benefit of your health insurance or a standalone offering from your employer. The core principle is that HIPAA governs specific entities, not the data itself in all contexts.

Intermediate

Understanding the structural application of HIPAA is the first layer. The next involves dissecting the specific mechanisms that protect your data when your wellness program operates within a group health plan. When your data is classified as PHI, the HIPAA Privacy Rule and Security Rule act as its guardians.

The Privacy Rule dictates who can access your information and for what purpose, while the Security Rule mandates specific administrative, physical, and technical safeguards for electronic PHI (ePHI). Think of the Privacy Rule as the “what” and “why” of data access and the Security Rule as the “how” of its protection.

Your data’s legal protection is determined by the program’s structure, not just the sensitivity of the information itself.

For a wellness program integrated with a group health plan, your employer, as the plan sponsor, may need access to certain PHI to administer the program. However, this access is not unfettered. The group health plan must generally obtain your written authorization before disclosing PHI to the employer.

This authorization must be clear and specific, informing you of precisely what information will be shared and for what reason. The principle of “minimum necessary” is also invoked, meaning the health plan should only disclose the least amount of information required for the specific administrative task.

The Role of Business Associates

Wellness programs often involve third-party vendors, such as labs that process your blood work for hormone analysis or technology platforms that track your biometric data. If these vendors handle PHI on behalf of a covered entity (your group health plan), they are designated as “business associates” under HIPAA.

This designation is significant because it legally obligates them to comply with the same HIPAA security and privacy rules as the covered entity itself. They must implement the same level of administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to protect your data. This extends the shield of HIPAA beyond the primary health plan to the entire ecosystem of partners involved in your wellness journey.

Data Protections beyond HIPAA

What about wellness programs that fall outside of HIPAA’s direct oversight, such as those offered directly by an employer or through a direct-to-consumer wellness app? Here, the privacy landscape becomes a patchwork of other regulations.

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are two prominent examples of laws that grant consumers rights over their personal data, which can include health information. These regulations often require clear privacy policies and explicit user consent for data collection and processing.

For instance, Google’s Health App Policy requires apps to provide comprehensive privacy notices and, in some cases, obtain specific consent for health-related research. This demonstrates a broader trend toward holding all collectors of health data to a higher standard of transparency and user control, even if they are not HIPAA-covered entities.

The following table outlines the primary legal frameworks and their general applicability, illustrating the tiered nature of health data protection.

| Regulatory Framework | Primary Applicability | Key Protections for Health Data |

|---|---|---|

| HIPAA | Health Plans, Healthcare Providers, and their Business Associates. | Controls use and disclosure of PHI; mandates security safeguards; requires patient authorization for many disclosures. |

| GDPR | Organizations processing the personal data of EU residents. | Requires explicit consent for data processing; grants individuals rights of access and erasure; mandates data protection by design. |

| CCPA | Businesses collecting personal information of California residents. | Grants consumers the right to know what data is collected and to opt-out of its sale. |

Academic

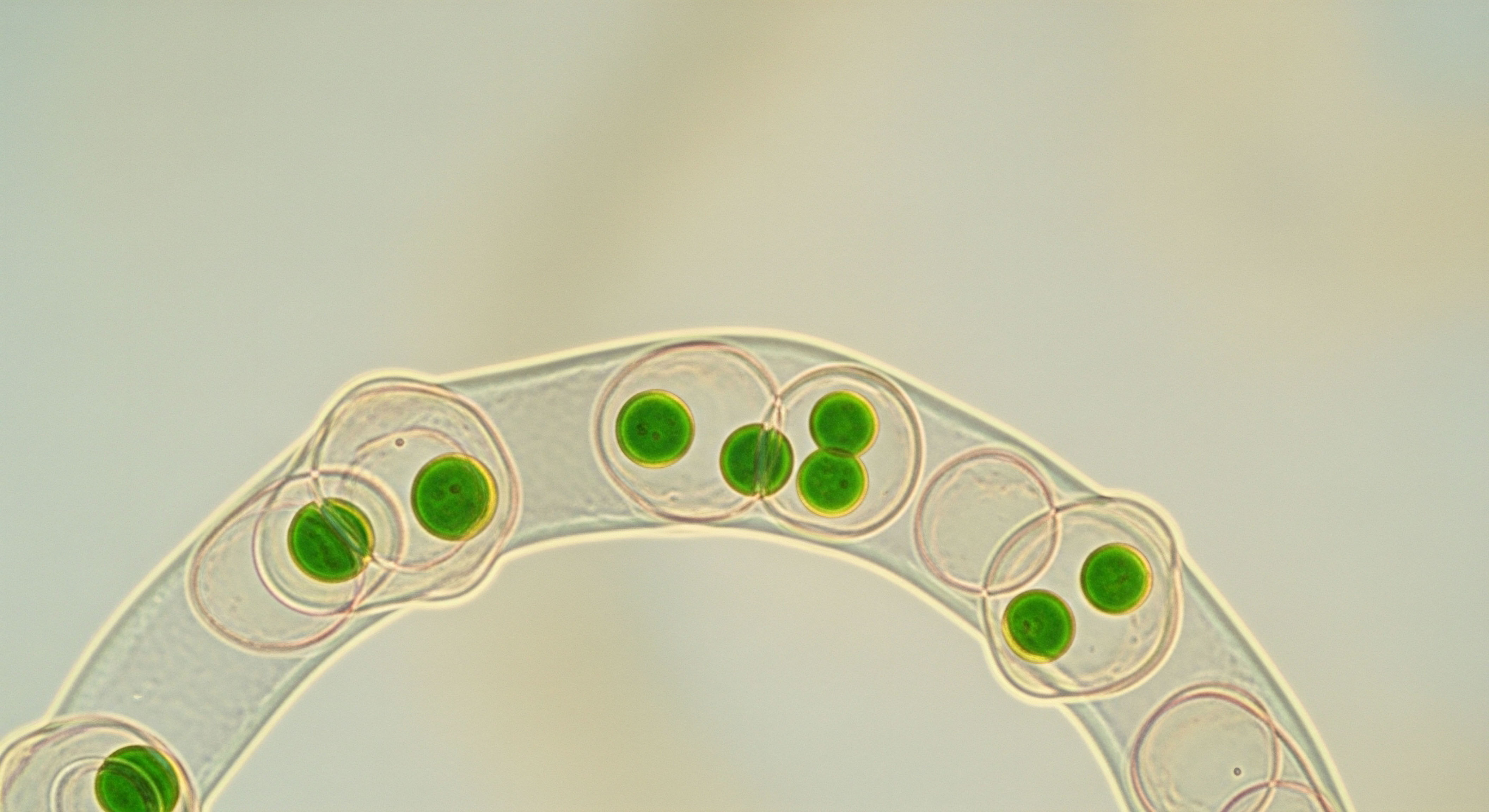

A sophisticated analysis of health data privacy in wellness programs requires moving beyond the legal frameworks themselves to examine the inherent vulnerabilities of the data. The very biometric and hormonal data that provides deep insights into your health ∞ such as heart rate variability, sleep patterns, or levels of circulating testosterone ∞ also presents unique challenges for privacy. One of the most significant of these is the risk of re-identification, even after data has been “de-identified.”

De-identification is the process of removing direct identifiers (like name and Social Security number) from a dataset to protect patient privacy, as defined by HIPAA. There are two primary methods for de-identification under HIPAA ∞ the “Safe Harbor” method, which involves removing 18 specific identifiers, and the “Expert Determination” method, where a qualified statistician attests that the risk of re-identification is very small.

Once de-identified, data is no longer considered PHI and can be used more freely for research. This process is foundational to advancing medical science, allowing researchers to analyze large datasets to discover new patterns and therapeutic targets.

What Is the True Anonymity of De-Identified Data?

The concept of true and permanent anonymity in de-identified data is becoming increasingly tenuous. The proliferation of publicly available datasets, from social media to voter registration records, creates an environment ripe for “linkage attacks.” A malicious actor could potentially cross-reference a de-identified health dataset with publicly available information to re-associate the data with a specific individual.

For example, researchers have demonstrated that it is possible to identify individuals by pairing patterns in physical mobility data from wearables with corresponding demographic data. The risk is amplified with the rich, continuous data streams generated by modern wellness technologies. As little as a few seconds of sensor data can sometimes be enough to create a unique “fingerprint” that can be used for identification.

The biological uniqueness that makes your health data valuable for personalization also makes it a powerful and potentially re-identifiable fingerprint.

This reality challenges the adequacy of traditional de-identification methods. The “Safe Harbor” approach, while straightforward, may not be sufficient to protect against re-identification in the era of big data. The “Expert Determination” method offers a more robust, risk-based approach, as it considers the context and the potential for linkage with other available information. However, even this method acknowledges that the risk of re-identification can be minimized but not entirely eliminated.

The Biometric Signature and Re-Identification Risk

The data from wearables and advanced diagnostics carries a high risk of re-identification precisely because it is so specific to an individual’s physiology. The following list details types of data commonly collected in wellness programs and their associated re-identification potential:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG) ∞ The waveform of a heartbeat is highly unique to an individual and can be used as a biometric identifier.

- Gait and Motion Data ∞ Accelerometer and gyroscope data from a smartphone or wearable can reveal a person’s unique walking pattern, which can be used for identification.

- Sleep Chronotypes ∞ Detailed sleep-wake patterns, tracked over time, can form a distinctive signature that aids in re-identification when combined with other data points.

- Hormonal Fluctuation Patterns ∞ While a single hormone level is not identifying, longitudinal data showing the cyclical patterns of hormones like cortisol or testosterone could, in theory, contribute to a unique profile.

This inherent identifiability means that entities handling such data must implement stringent data governance and use agreements. These agreements can legally prohibit recipients of de-identified data from attempting to re-identify individuals and can include audit rights to ensure compliance. The table below compares the two HIPAA de-identification methods in the context of modern data risks.

| De-Identification Method | Process | Advantages | Limitations in the Modern Data Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safe Harbor | Removal of 18 specific identifiers (e.g. name, address, dates). | Clear, prescriptive, and easy to implement. | May be insufficient to prevent re-identification from rich biometric or genomic data streams. |

| Expert Determination | A qualified expert applies statistical or scientific principles to render information not individually identifiable. | More flexible and risk-based; can be applied to complex datasets. | Requires specialized expertise; acknowledges that re-identification risk is never zero. |

References

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2015). HIPAA Privacy and Security and Workplace Wellness Programs. HHS.gov.

- Paubox. (2023). HIPAA and workplace wellness programs.

- Barrow Group Insurance. (2024). Workplace Wellness Programs ∞ ERISA, COBRA and HIPAA.

- Compliancy Group. (2023). HIPAA Workplace Wellness Program Regulations.

- Gkoulalas-Divanis, A. & Loukides, G. (2015). Medical data privacy handbook. Springer.

- Shuaib, M. Alam, S. Alam, M. S. & Hassan, M. M. (2021). A systematic review on the use of wearable and smartphone-based sensors for human activity and health-related task recognition. Sensors, 21(8), 2643.

- El Emam, K. & Alvarez, C. (2015). A critical appraisal of the Safe Harbor method for the de-identification of protected health information. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(2), 435-445.

- Malin, B. & Sweeney, L. (2004). How (not) to protect patient privacy in a distributed research network. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 11(5), 333-335.

- Ohm, P. (2010). Broken promises of privacy ∞ Responding to the surprising failure of anonymization. UCLA Law Review, 57, 1701.

- TermsFeed. (n.d.). Privacy guidelines for health apps.

Reflection

You have now explored the intricate landscape of health data privacy, from the foundational legal structures to the subtle, yet profound, risks inherent in the data itself. This knowledge is a critical tool in your wellness arsenal. It transforms you from a passive participant into an informed partner in your own health journey.

As you move forward, consider the wellness programs and platforms you engage with not just through the lens of their potential benefits, but also through the lens of their commitment to protecting your biological identity. The ultimate goal is a partnership where the pursuit of vitality does not require a compromise on privacy, but is instead built upon a foundation of trust and transparent stewardship of your most personal information.

Glossary

wellness program

health data

data protection

hipaa

protected health information

phi

group health plan

health plan

health information

hipaa privacy rule

business associates

wellness programs

ccpa

gdpr

data privacy

de-identification

safe harbor