Fundamentals

You may be experiencing a constellation of symptoms that feel disconnected, yet deeply personal. A persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve, a subtle shift in your mood or cognitive clarity, or changes in your body composition that don’t seem to correspond with your diet and exercise efforts. These experiences are valid.

They are signals from your body’s intricate internal communication network, a system where the smallest changes in one area can create significant ripples in another. Your journey to understanding these signals begins with appreciating the profound connection between two of the body’s master regulators ∞ testosterone and the thyroid hormone system.

We will explore this relationship not as a series of isolated facts, but as a dynamic interplay that governs your energy, metabolism, and overall sense of vitality. Understanding this biological conversation is the first step toward reclaiming control over your health narrative.

At the center of this conversation are two powerful hormonal axes ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls testosterone production, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, which governs thyroid function. Think of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, located at the base of your brain, as the central command center.

This command center sends out signaling hormones that instruct the gonads (testes in men, ovaries in women) and the thyroid gland to produce their respective hormones. These systems are designed to work in a state of delicate equilibrium, constantly adjusting to maintain homeostasis. A disruption in one axis can, and often does, influence the other. This interconnectedness is a cornerstone of endocrine health, and it is where the story of your personal symptoms often finds its biological roots.

The Critical Role of Transport Proteins

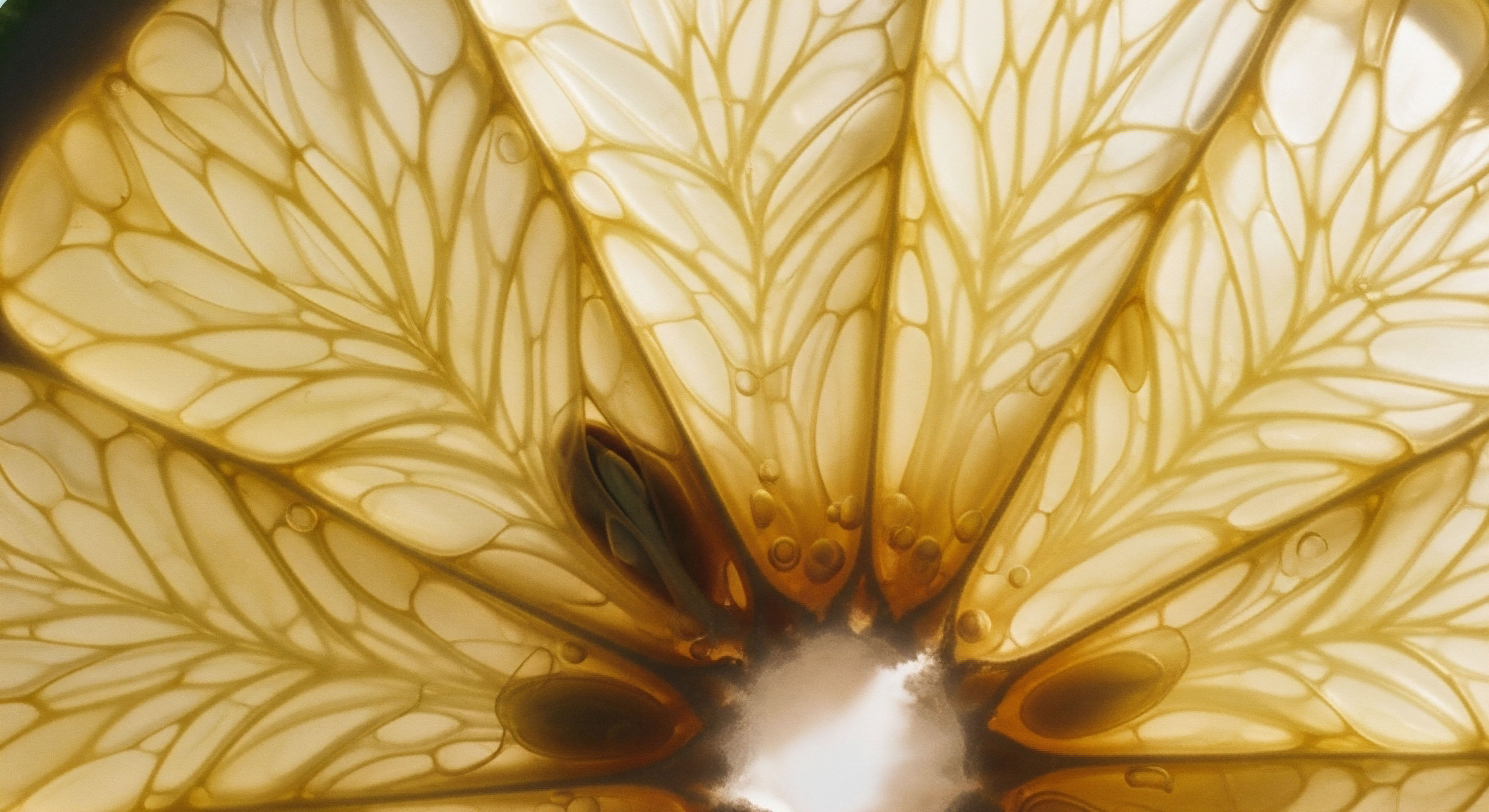

Hormones like testosterone and thyroxine (T4) do not simply float freely in the bloodstream. They are largely bound to specific carrier proteins, which act like designated chauffeurs, transporting them throughout the body. Only a small fraction of these hormones is “free” or unbound at any given time.

This free portion is the biologically active component, able to enter cells and exert its effects. Two of these transport proteins are central to the testosterone-thyroid relationship ∞ Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) and Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG).

Thyroid hormone levels directly influence the liver’s production of SHBG. When thyroid hormone levels are high (hyperthyroidism), SHBG levels tend to increase. This elevation in SHBG means more testosterone becomes bound, reducing the amount of free, active testosterone available to your tissues.

Consequently, an individual with an overactive thyroid might present with symptoms of low testosterone, not because their body is producing less, but because more of it is being held in an inactive state. Conversely, low thyroid hormone levels (hypothyroidism) can lead to lower SHBG, which might initially seem beneficial for free testosterone. The relationship, however, is complex, as hypothyroidism also disrupts the primary signals for testosterone production from the pituitary gland.

The availability of active testosterone is directly influenced by thyroid-regulated transport proteins in the blood.

Testosterone, in turn, exerts its own influence on these transport systems. Specifically, androgens have been shown to decrease the concentration of Thyroxine-Binding Globulin (TBG), the primary carrier for thyroid hormones in the blood.

When testosterone levels are optimized, particularly through therapeutic interventions like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), the subsequent reduction in TBG can lead to an increase in the amount of free T4 and T3. This means more thyroid hormone is available to the cells. For some individuals, this can be a beneficial effect, enhancing metabolic rate and energy levels.

For others, particularly those with pre-existing or borderline hyperthyroid conditions, this shift could potentially exacerbate symptoms. This is a clear example of the bidirectional communication between these two hormonal systems. The balance is delicate, and optimizing one system requires careful consideration of the other.

How Is the Pituitary Gland Involved?

The pituitary gland is the master conductor of the endocrine orchestra. It releases Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) to signal the thyroid gland and Luteinizing Hormone (LH) to signal the testes to produce testosterone. A problem within the pituitary itself can create a combined deficiency in both systems.

If the pituitary is not sending enough TSH, hypothyroidism can result. If it fails to send enough LH, secondary hypogonadism (low testosterone) occurs. Therefore, when an individual presents with symptoms suggestive of both low thyroid and low testosterone, a thorough evaluation must include an assessment of pituitary function. It is a powerful reminder that symptoms are not isolated events but are often downstream consequences of a disruption in the central regulatory mechanisms of the body.

Understanding these foundational interactions is the first step. It moves the conversation from a list of symptoms to a systems-based view of your biology. The fatigue you feel is not just “tiredness”; it is a potential signal of a breakdown in the very systems that generate and regulate cellular energy.

The changes in your mood are not arbitrary; they can be linked to the availability of hormones that are essential for healthy brain function. This perspective is the foundation upon which a truly personalized and effective wellness protocol is built.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond the foundational concepts of transport proteins and pituitary signaling, we arrive at a more granular level of interaction ∞ the enzymatic conversion of thyroid hormones. This is where the direct influence of testosterone on thyroid function becomes particularly evident, operating at a cellular level that can profoundly impact your metabolic reality.

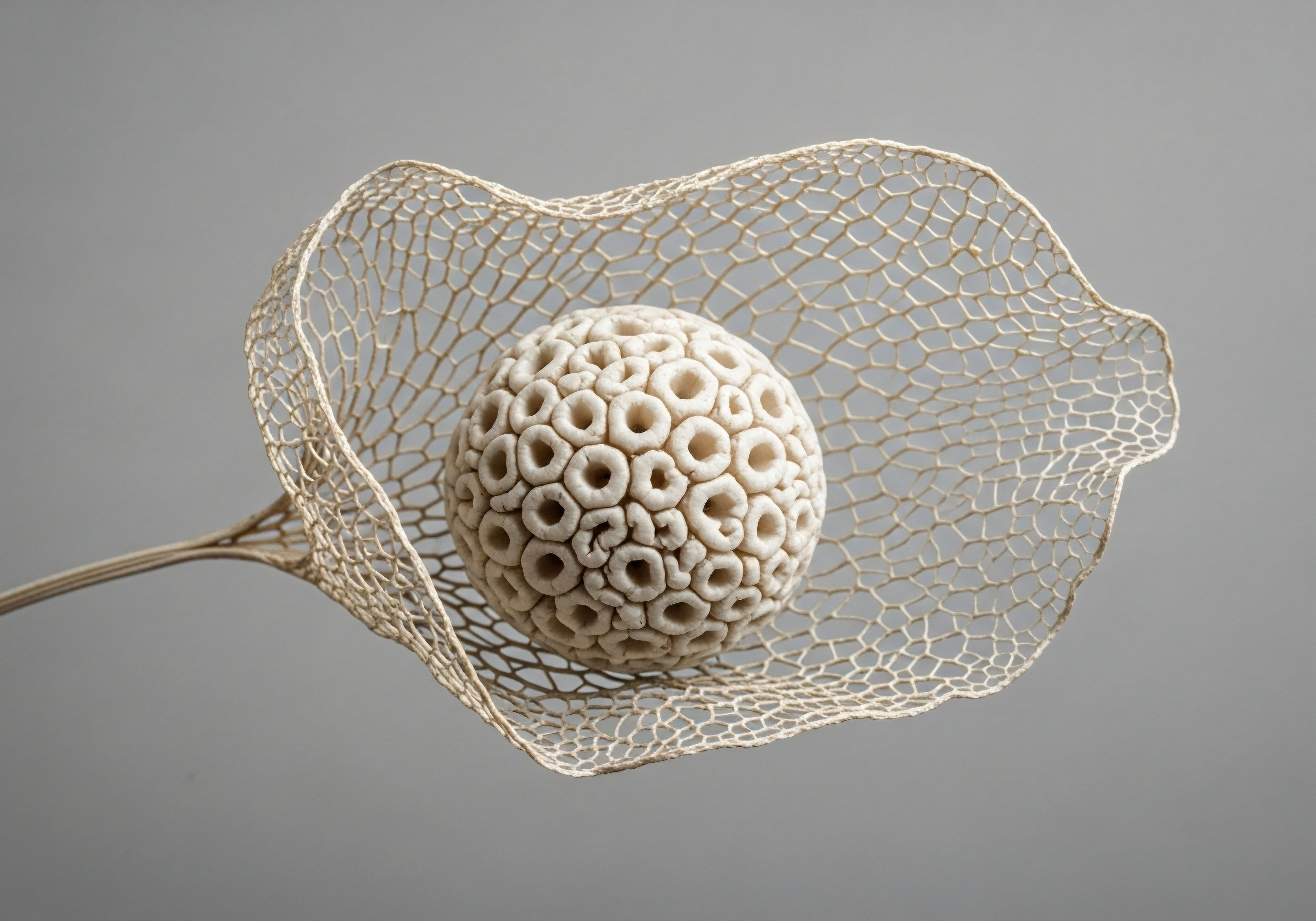

The thyroid gland primarily produces an inactive or “storage” form of thyroid hormone called thyroxine (T4). For your body to utilize this hormone to regulate metabolism, it must first be converted into the more biologically active form, triiodothyronine (T3). This conversion process is not passive; it is an active, enzymatic process managed by a family of enzymes known as deiodinases. The efficiency of this conversion is a critical determinant of your overall thyroid status.

The Deiodinase Enzyme Family

The deiodinase enzymes are responsible for removing specific iodine atoms from the T4 molecule, a chemical reaction that activates or deactivates it. There are three main types of deiodinase enzymes, each with a distinct role and location in the body. Their collective action determines how much active T3 is available to your cells, effectively controlling the “volume” of your metabolic engine.

- Type 1 Deiodinase (D1) ∞ Found primarily in the liver, kidneys, and thyroid gland, D1 is responsible for a significant portion of the circulating T3 in the bloodstream. It can both activate T4 to T3 and clear inactive thyroid hormone metabolites. Its function provides a systemic supply of active T3 for the entire body.

- Type 2 Deiodinase (D2) ∞ Located in tissues like the brain, pituitary gland, and brown adipose tissue, D2’s primary role is to increase intracellular T3 levels. It acts locally, ensuring that these specific, highly sensitive tissues have a consistent supply of active thyroid hormone, even when circulating levels might be low. This is a protective mechanism for critical organs.

- Type 3 Deiodinase (D3) ∞ This enzyme is the primary “off-switch.” It inactivates thyroid hormone by converting T4 to reverse T3 (rT3) and T3 to T2, both of which are biologically inert. D3 is crucial for protecting tissues from excessive thyroid hormone exposure, particularly during development and in certain disease states.

The balance of activity between these enzymes is what truly defines your thyroid status at the cellular level. Standard blood tests that only measure TSH and T4 may not capture the full picture. An individual could have perfectly normal T4 levels, but if the conversion to T3 is impaired, they will experience the functional symptoms of hypothyroidism because their cells are not receiving the active hormone they need. This is where testosterone enters the equation in a very direct way.

Testosterone can directly inhibit the enzyme responsible for converting inactive thyroid hormone into its active form.

Testosterone’s Direct Effect on T4 to T3 Conversion

Clinical and preclinical research has demonstrated that androgens, including testosterone and its more potent metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT), can exert an inhibitory effect on Type 1 Deiodinase (D1) activity. A study published in the Journal of Endocrinology found that in castrated animal models, testosterone replacement diminished D1 activity.

Conversely, blocking the conversion of testosterone to DHT with a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor actually enhanced D1 activity. This suggests that androgens act as a modulating brake on the systemic conversion of T4 to T3. From a clinical perspective, this mechanism has significant implications.

For a man undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), increasing testosterone levels could potentially slow down the T4 to T3 conversion process. If this individual already has suboptimal deiodinase function, the introduction of therapeutic testosterone might unmask or worsen symptoms of hypothyroidism, such as fatigue, cold intolerance, or weight gain, despite having “normal” TSH and T4 levels on a lab report.

This is a classic example of how a systems-based approach is essential. A practitioner must look beyond the isolated numbers and consider the functional interplay between these hormonal systems.

What Are the Clinical Implications of This Interaction?

This interaction underscores the importance of comprehensive hormonal assessments. When evaluating a patient for hormone optimization protocols, it is insufficient to look at testosterone or thyroid in isolation. A complete thyroid panel, including not just TSH and free T4, but also free T3 and potentially reverse T3, is necessary to understand the full dynamics of thyroid hormone conversion. The following table outlines the key functions of the deiodinase enzymes and the potential impact of androgens.

| Enzyme | Primary Location | Primary Function | Reported Androgen Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 Deiodinase (D1) | Liver, Kidneys, Thyroid | Systemic T3 Production & Clearance | Inhibitory effect from testosterone and DHT |

| Type 2 Deiodinase (D2) | Brain, Pituitary, Brown Fat | Local (intracellular) T3 Production | Less directly studied in relation to androgens |

| Type 3 Deiodinase (D3) | Placenta, Skin, Fetal Tissues | Inactivation of T4 and T3 | Regulation is complex and less defined by androgens |

For individuals on hormonal optimization protocols, such as the TRT regimens outlined in the core clinical pillars, this knowledge is directly actionable. If a patient on TRT reports persistent fatigue or other hypothyroid symptoms, a clinician’s next step should be to evaluate their T3 levels.

If T3 is low relative to T4, it may indicate poor conversion. The solution might not be to simply increase the thyroid medication dose, but to support the conversion process itself. This could involve nutritional cofactors like selenium and zinc, which are essential for deiodinase function, or in some cases, the direct addition of T3 (Liothyronine) to their protocol. This approach is a hallmark of personalized medicine, tailoring the intervention to the specific biological mechanism that is being affected.

Academic

The most sophisticated level of interaction between the testosterone and thyroid signaling pathways occurs at the very heart of cellular function ∞ the nucleus. Here, the communication transcends systemic hormonal levels and enzymatic conversions, entering the realm of molecular biology and genetic expression.

The concept of nuclear receptor crosstalk provides a compelling framework for understanding the deep, integrative relationship between androgens and thyroid hormones. Both the Androgen Receptor (AR) and the Thyroid Hormone Receptor (TR) belong to the same superfamily of nuclear receptors.

These proteins, when activated by their respective hormones (ligands), translocate to the cell nucleus and function as transcription factors, binding to specific DNA sequences to regulate the expression of target genes. The potential for these two pathways to influence one another directly at this genomic level represents the ultimate integration of their biological signals.

Genomic Crosstalk and Receptor Regulation

Emerging evidence indicates that this crosstalk is bidirectional. Thyroid hormones have been shown to directly influence the expression and sensitivity of the Androgen Receptor. Research published in the European Thyroid Journal highlights studies demonstrating that thyroid hormones can interact with the promoter region of the AR gene.

This interaction can increase AR expression, effectively making tissues more sensitive to the androgens circulating in the bloodstream. From a functional perspective, this means that optimal thyroid function is a prerequisite for the full expression of androgenic effects. An individual with hypothyroidism may have reduced AR density, leading to a blunted response to their endogenous testosterone or to therapeutic testosterone.

This could explain why some individuals on TRT do not experience the full benefits until their thyroid status is also optimized. The thyroid system is, in this sense, a permissive factor for androgen action.

Conversely, the androgen signaling pathway appears to have a reciprocal influence on thyroid-related gene expression. The identification of Androgen Response Elements (AREs) ∞ specific DNA sequences where the activated AR binds ∞ in the promoter regions of genes related to thyroid function suggests a direct regulatory role for testosterone.

For instance, AREs have been identified in the promoter regions of genes for deiodinase enzymes and even for thyroid hormone receptor isoforms in some vertebrates. This suggests that testosterone can directly, at a genomic level, modulate the machinery of thyroid hormone activation and signaling.

This is a far more intricate mechanism than simple enzyme inhibition; it is a direct intervention in the genetic transcription of the thyroid system’s key components. This molecular dialogue ensures that the body’s directives for metabolic rate and for anabolic growth are coordinated and integrated, rather than operating in isolation.

The genetic instructions for androgen and thyroid function are directly intertwined through shared regulatory mechanisms on DNA.

What Are the Broader Implications of Receptor Crosstalk?

The clinical and physiological implications of this nuclear crosstalk are substantial. It suggests that the hormonal state of one system can fundamentally alter the functional capacity of the other. This has particular relevance in the context of both pathology and therapeutic intervention.

For example, the link between hyperthyroidism and certain androgen-dependent conditions, like prostate cancer, may be partially explained by this crosstalk. Elevated thyroid hormones could potentially upregulate Androgen Receptor expression, sensitizing prostate tissue to androgens and contributing to its growth. The following table summarizes this complex molecular interplay.

| Signaling Pathway | Mechanism of Action | Target | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid Hormone (T3) | Binds to Thyroid Response Elements (TREs) in the promoter region of the Androgen Receptor (AR) gene. | Androgen Receptor Gene | Increases transcription and expression of AR, enhancing tissue sensitivity to androgens. |

| Testosterone (via AR) | Binds to Androgen Response Elements (AREs) in the promoter regions of thyroid-related genes. | Genes for Deiodinases, Thyroid Receptors | Modulates the expression of key components of the thyroid signaling pathway. |

This level of understanding moves hormonal optimization beyond simple replacement and into the domain of system recalibration. For a patient on a comprehensive wellness protocol, this means that interventions must be considered for their network effects.

Administering Gonadorelin to maintain natural testosterone production alongside TRT is not just about testicular function; it is about preserving the entire HPG axis signaling which, as we see, is in constant communication with the HPT axis. Similarly, the use of peptides like Sermorelin or CJC-1295 to support Growth Hormone (GH) release must be viewed through this integrative lens.

GH production is also dependent on normal thyroid hormone levels, adding another layer to this interconnected network. The goal of advanced hormonal therapy is to restore a state of intelligent biological balance, recognizing that each input will have cascading effects throughout the entire endocrine system. This requires a deep appreciation for the molecular conversations that are constantly occurring within every cell of the body.

How Does This Affect Personalized Treatment Protocols?

This academic understanding translates directly into superior clinical practice. When designing a protocol for a man experiencing andropause or a woman navigating perimenopause, a clinician armed with this knowledge understands that prescribing testosterone is only one part of the solution. They will proactively assess thyroid function with a comprehensive panel.

They will anticipate that changes in testosterone may alter free thyroid hormone levels via TBG reduction and may also influence T3 conversion via deiodinase inhibition. Most importantly, they will understand that for the testosterone to be maximally effective, the thyroid hormone receptors and the entire downstream signaling pathway must be functioning optimally.

This systems-biology perspective is the defining characteristic of a truly advanced and personalized approach to hormonal health. It is about treating the individual, not just the lab value, and restoring the body’s own intricate and intelligent regulatory networks.

References

- Cavaliere, H. et al. “The effect of oral testosterone on serum TBG levels in alcoholic cirrhotic men.” Hormone and Metabolic Research, vol. 20, no. 10, 1988, pp. 637-40.

- Federman, Daniel D. et al. “Effects of Methyl Testosterone on Thyroid Function, Thyroxine Metabolism, and Thyroxine-Binding Protein.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 37, no. 7, 1958, pp. 1024-30.

- Angileri, F. et al. “The androgen-thyroid hormone crosstalk in prostate cancer and the clinical implications.” European Thyroid Journal, vol. 12, no. 3, 2023, e220228.

- Curcio-Von-Linsingen, M. et al. “Deiodinase type 1 activity is expressed in the prostate of pubescent rats and is modulated by thyroid hormones, prolactin and sex hormones.” Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 190, no. 2, 2006, pp. 363-71.

- Bianco, Antonio C. et al. “Cellular and Molecular Basis of Deiodinase-Regulated Thyroid Hormone Signaling.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 29, no. 7, 2008, pp. 898-938.

- Gauthier, K. et al. “Different functions for the thyroid hormone receptors TRalpha and TRbeta in the control of thyroid hormone production and post-natal development.” The EMBO Journal, vol. 18, no. 3, 1999, pp. 623-31.

- Wajner, Simone M. and Ana Luiza Maia. “New insights into the regulation of deiodinase activity.” Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia, vol. 56, no. 4, 2012, pp. 249-61.

Reflection

A Systems Perspective on Your Biology

The information presented here offers a map of the intricate biological landscape that governs your vitality. It reveals that the feelings of fatigue, mental fog, or physical decline are not isolated failures but signals within a deeply interconnected system.

Your body is not a collection of separate parts; it is a unified whole, where the conversation between testosterone and the thyroid is just one of many dialogues constantly taking place. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It shifts the focus from chasing symptoms to understanding systems.

It allows you to ask more informed questions and to seek solutions that honor the complexity of your own unique physiology. Your personal health journey is one of discovery, and this understanding is the first, most meaningful step toward becoming an active participant in your own wellness. The path forward is one of recalibration, guided by data, and centered on restoring the intelligent balance that is inherent to your biology.