Fundamentals

The Body as an Internal Incentive System

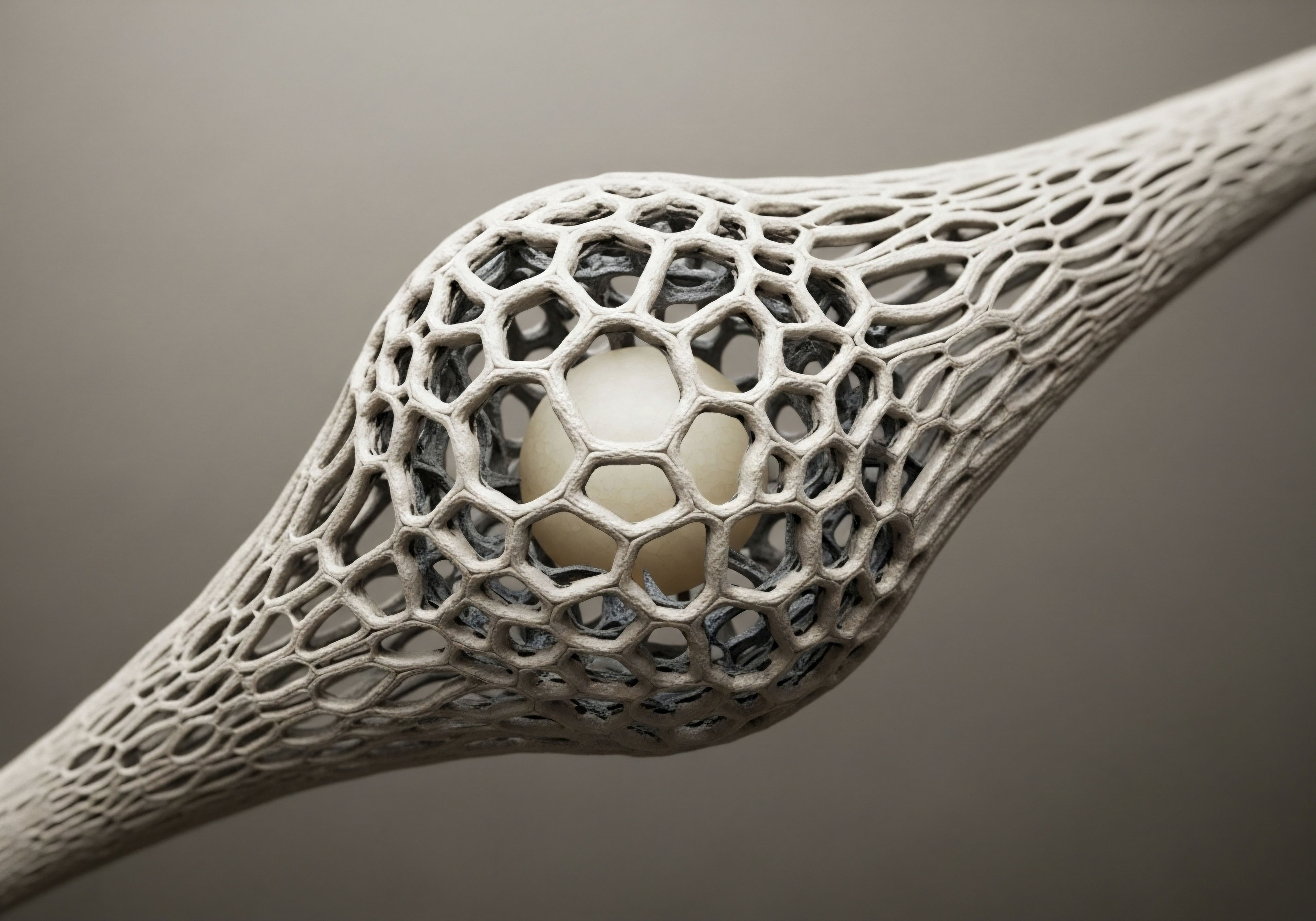

Your body operates on a sophisticated system of internal incentives. Every sensation of energy, clarity, and well being is the result of a complex biochemical conversation, a cascade of hormones and neurotransmitters rewarding actions that support its equilibrium.

When you feel a surge of vitality after a nutrient dense meal or the mental calm following deep sleep, you are experiencing your physiology’s native reward system. This internal architecture is the foundational blueprint for health. The journey to reclaiming function begins with understanding that your symptoms are signals from this system, communications about its status and its needs.

External wellness programs, with their own set of incentives, represent an attempt to interface with this deeply personal, biological system. They are a structured approach to encourage behaviors that, in theory, align with your body’s intrinsic goals for vitality. The regulations governing these programs establish the boundaries of this external influence.

They define how a workplace initiative can encourage you toward a health goal, creating a framework that acknowledges the sensitive interplay between external motivators and your internal biological landscape. These rules are a recognition that achieving metabolic and hormonal balance is a process that requires both support and a respect for individual biological reality.

Regulatory limits on wellness incentives are designed to guide external health programs, ensuring they support your body’s internal biological journey without becoming coercive.

What Are Participatory versus Health Contingent Programs?

Wellness initiatives are broadly classified into two distinct types, each with a different level of engagement with your personal health data. Understanding this distinction is the first step in seeing how these programs are structured. One path encourages general participation in health related activities, while the other ties incentives directly to specific physiological outcomes. This structural difference determines the regulatory limits placed upon them.

- Participatory Wellness Programs These programs reward you for taking part in a health related activity. Examples include attending an educational seminar on nutrition or completing a health risk assessment. The key element is that the reward is based on participation alone, not on the results or any change in your biometric data. There are no federally mandated limits on the incentives for these programs.

- Health Contingent Wellness Programs These programs require you to meet a specific standard related to a health factor to earn a reward. This category is further divided into two sub-types ∞ ‘activity only’ programs, which involve activities like walking or exercise, and ‘outcome based’ programs, which are tied to achieving a specific health goal, such as a target cholesterol level or blood pressure reading.

Intermediate

The Architecture of Incentive Limits

The regulatory framework for health contingent wellness programs, primarily established under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA), sets clear financial boundaries. These limits are calculated as a percentage of the total cost of health coverage, which includes both your contribution and your employer’s.

This structure is designed to allow for meaningful incentives while providing a safeguard against overly punitive measures that could create barriers to care. The regulations are an acknowledgment of the complexities of human biology and behavior, creating a system that encourages progress while accommodating individual health realities.

The incentive structure is built upon a foundational limit for general health goals, with a significant increase for programs targeting tobacco use. This differentiation reflects a public health understanding of the profound physiological and psychological grip of nicotine addiction, a dependency rooted in the brain’s dopamine reward pathways.

Overcoming this requires a substantial counter-incentive. For all other health metrics, the lower threshold encourages sustainable, long term lifestyle adjustments over drastic, short term changes that could disrupt the body’s delicate endocrine and metabolic balance.

| Program Type | Maximum Incentive Limit | Basis of Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| General Health & Activity-Based | 30% of the cost of health coverage | Applies to programs targeting metrics like BMI, cholesterol, or blood pressure. |

| Tobacco Use Prevention or Reduction | 50% of the cost of health coverage | Applies to programs specifically designed to help individuals quit smoking or using tobacco products. |

How Do Reasonable Alternative Standards Support Your Biology?

A central pillar of this regulatory structure is the requirement for a Reasonable Alternative Standard (RAS). Your body’s ability to meet a specific health target, such as a certain BMI or blood pressure level, is not solely a matter of willpower.

It is a complex expression of your genetic predispositions, your current hormonal status, and your unique metabolic function. A person with thyroid hormone resistance, for example, faces a distinct physiological challenge in managing weight compared to someone with a fully optimized thyroid axis. The RAS mandate acknowledges this biological individuality.

The Reasonable Alternative Standard ensures that wellness programs account for individual biological realities, offering pathways to success that respect your unique physiology.

If a medical condition prevents you from meeting the primary standard of a health contingent program, the plan must provide another way for you to earn the full reward. This could involve completing an educational course, working with a health coach, or following a personalized plan from your physician.

The RAS transforms a potentially rigid, one size fits all program into a more flexible and responsive tool. It is a clinical and ethical safeguard, ensuring that the goal remains health promotion, not penalization for a physiological state that may be outside of your immediate control.

Academic

Incentives and the Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis

The conventional model of health contingent incentives operates on a behavioral economics framework, positing that external financial rewards can effectively modify health related actions. A deeper, neuroendocrinological perspective reveals a more complex reality. The body’s primary system for managing stress and motivation is the Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) axis.

Chronic workplace stress, a state these wellness programs implicitly aim to mitigate, induces HPA axis dysregulation, leading to elevated cortisol, insulin resistance, and a metabolic state that actively resists the very changes the incentives are designed to promote, such as fat loss or improved glycemic control.

A financial incentive, therefore, is not acting in a vacuum. It is a single, extrinsic input into a system already governed by powerful, intrinsic hormonal signals. For an individual with a dysregulated HPA axis, the pressure to meet an outcome based target can itself become a chronic stressor, potentially exacerbating the underlying physiological imbalance.

The cortisol-driven catabolic state and impaired glucose metabolism are potent biological forces. The question then becomes whether a 30% premium reduction is a sufficient counter-stimulus to the deeply ingrained biochemical pathways forged by chronic stress and hormonal dysregulation. The answer, from a systems biology standpoint, is likely that it is not, pointing to a fundamental limitation in using purely economic levers to solve complex physiological problems.

A purely financial incentive may be an insufficient tool to counteract the powerful biochemical pathways established by chronic stress and HPA axis dysregulation.

The Limitations of Biometric Data as Health Proxies

Health contingent programs are predicated on the measurement of specific biometric markers, such as Body Mass Index (BMI), LDL cholesterol, or fasting glucose. While these data points are valuable clinical indicators, their use as the sole determinants for rewards reveals a reductionist view of human health.

Each marker is a single snapshot of an incredibly dynamic and interconnected system. For instance, a person’s lipid panel is profoundly influenced by the interplay of thyroid hormones, insulin sensitivity, and sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen. A suboptimal LDL level may be a symptom of underlying hypothyroidism or metabolic syndrome, a systemic issue that cannot be resolved by a singular focus on diet or exercise without addressing the root hormonal imbalance.

This reliance on isolated biomarkers creates a potential for clinical dissonance. A program may incentivize a low fat diet to reduce LDL cholesterol, yet for many individuals, particularly women in perimenopause, healthy dietary fats are crucial precursors for steroid hormone production, including estrogen and testosterone.

In such a case, the program’s goal is in direct conflict with the body’s physiological needs for hormonal synthesis and balance. True wellness optimization requires a holistic interpretation of lab data within the context of the entire endocrine system, a level of personalization that standardized, population level incentive programs are structurally ill equipped to provide.

| Biometric Marker | Primary Endocrine & Metabolic Influences | Potential for Misinterpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Thyroid Axis (T3/T4), Insulin, Cortisol, Leptin, Ghrelin | Fails to distinguish between adipose and muscle tissue; ignores hormonal drivers of fat storage. |

| LDL Cholesterol | Thyroid Hormones, Testosterone, Estrogen, Insulin Sensitivity | Elevated LDL can be a symptom of hypothyroidism; low-fat diets may impair sex hormone production. |

| Fasting Glucose | Insulin, Glucagon, Cortisol, Growth Hormone, Epinephrine | Chronically high cortisol from stress can elevate glucose, independent of dietary sugar intake. |

Are These Incentive Limits Biologically Meaningful?

The established incentive limits, while logical from a policy and economic perspective, lack a clear physiological basis. There is no clinical data to suggest that a financial reward equivalent to 30% of an insurance premium is the precise threshold required to stimulate the necessary behavioral and biological changes for long term health.

The process of reversing metabolic syndrome or re-sensitizing insulin receptors is a slow, complex biological project that unfolds over months and years, not fiscal quarters. The regulations create a framework for program design, yet they do not, and cannot, align with the variable and highly personal timeline of physiological healing and adaptation.

- Neurochemical Adaptation The brain’s reward circuitry, driven by neurotransmitters like dopamine, adapts over time. An external incentive may initially provide a motivational surge, but its effect can diminish as the brain habituates to the reward.

- Hormonal Inertia The endocrine system seeks homeostasis. A body that has been in a state of insulin resistance for years has established powerful hormonal feedback loops that resist change. Overcoming this inertia requires consistent, long-term intervention that may not align with the annual qualification cycle of a wellness program.

- Genetic Heterogeneity Individual genetic variations, such as polymorphisms in the FTO gene (associated with obesity) or MTHFR gene (affecting methylation and detoxification), create different biological starting points and different responses to interventions. A single incentive structure cannot account for this genetic diversity.

References

- U.S. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and the Treasury. “Final Rules for Nondiscrimination in Health Coverage in the Group Market.” Federal Register, vol. 78, no. 106, 3 June 2013, pp. 33158-33209.

- Madison, Kristin M. “The Law and Policy of Workplace Wellness Programs.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, vol. 41, no. 4, 2016, pp. 603-647.

- Sapolsky, Robert M. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers ∞ The Acclaimed Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping. Henry Holt and Co. 2004.

- Horwitz, Jill R. and Austin Nichols. “Workplace Wellness Programs ∞ The Law, The Evidence, The Controversy.” The Milbank Quarterly, vol. 95, no. 3, 2017, pp. 474-482.

- Baicker, Katherine, et al. “The Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes ∞ A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA, vol. 321, no. 15, 2019, pp. 1491-1501.

- Schmidt, Harald, et al. “Voluntary and Mandatory Approaches to Workplace Wellness.” Health Affairs, vol. 35, no. 11, 2016, pp. 1978-1985.

- Jones, Damon, et al. “What Do Workplace Wellness Programs Do? Evidence from the Illinois Workplace Wellness Study.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 134, no. 4, 2019, pp. 1747-1791.

Reflection

The knowledge of these external frameworks is a valuable tool, offering insight into the systems designed to support your health journey. Yet, the most profound work begins when you turn your focus inward. The numbers on a lab report and the incentives in a wellness program are data points, external signals pointing you back to the core truth of your own biology.

Your lived experience, the daily sensations of energy or fatigue, mental clarity or fog, are the most immediate and vital feedback you will ever receive. Use this understanding of the external rules as a catalyst to become a more astute observer of your internal ones, beginning the process of aligning your daily choices with the deep, biological incentives of your own body.