Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent sense of imbalance, a fatigue that sleep does not resolve, or notice changes in your body that seem disconnected from your lifestyle. These experiences are valid and important signals. They are your body’s method of communicating a profound shift in its internal environment.

Understanding the source of this disruption is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. The conversation often begins with hormones, the body’s intricate chemical messaging system that governs everything from your metabolism and mood to your reproductive health. When this system is disturbed, the effects ripple through your entire sense of well-being.

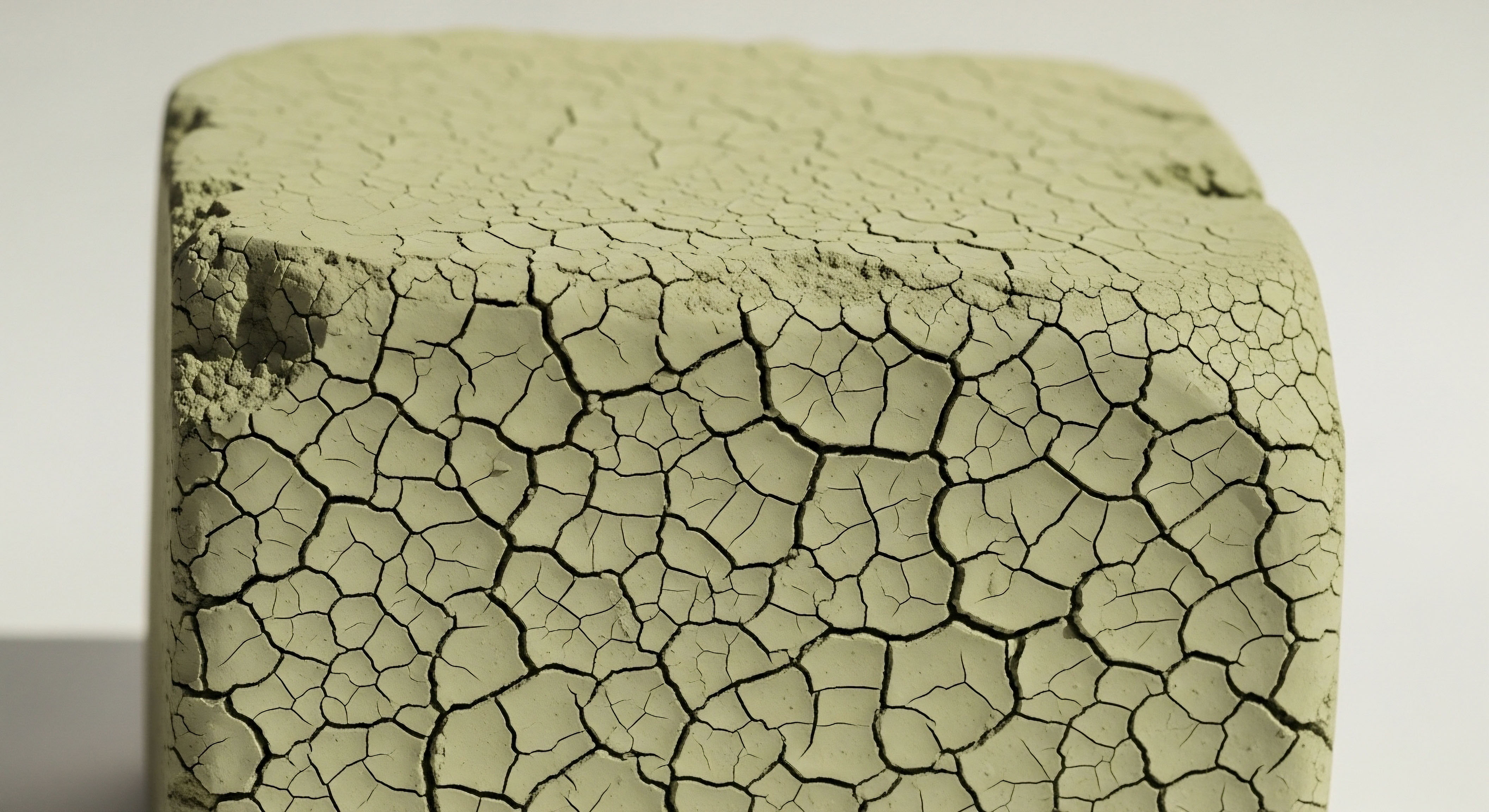

One of the most complex and pervasive sources of this disturbance comes from outside the body, from a class of substances known as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs).

These compounds are found throughout our modern world, in plastics, pesticides, cosmetics, and household products. Their defining characteristic is their ability to interfere with the normal function of your endocrine system. They can mimic your natural hormones, block their action, or alter how they are produced, transported, and metabolized.

This interference is the root of the scientific challenge. Identifying a specific EDC as the cause of a health issue is exceptionally difficult because these chemicals do not act like conventional poisons. Their effects are subtle, often delayed, and deeply dependent on the timing of exposure.

The endocrine system functions as a complex, interconnected network, and EDCs introduce unpredictable interference that science is still working to fully map.

The Body’s Internal Communication Network

Your endocrine system is a marvel of biological engineering. It is composed of glands ∞ like the thyroid, adrenals, ovaries, and testes ∞ that release hormones directly into the bloodstream. These hormones travel to target cells throughout the body, binding to specific receptors to deliver instructions.

Think of it as a highly precise postal service, where each hormone is a letter with a specific address and a clear message. This system maintains homeostasis, a state of internal balance, by constantly adjusting to internal and external cues. It regulates your sleep-wake cycle, manages your stress response through the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, and directs reproductive function via the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

EDCs disrupt this communication in several ways:

- Mimicry ∞ Some EDCs have a molecular structure similar to natural hormones, allowing them to bind to hormone receptors and trigger a response. For example, certain xenoestrogens found in plastics can mimic estrogen, sending inappropriate growth signals to tissues.

- Blocking ∞ Other EDCs can occupy a hormone’s receptor without activating it, effectively blocking the natural hormone from delivering its message. This can lead to a state of functional hormone deficiency even when hormone levels appear normal.

- Interference ∞ EDCs can also disrupt the synthesis, transport, or breakdown of natural hormones, altering their concentration in the bloodstream and disrupting the delicate feedback loops that keep the system in balance.

Why Timing Is Everything

A central challenge in understanding EDCs is the concept of critical windows of susceptibility. The endocrine system is particularly vulnerable during periods of rapid development, such as in the womb, during infancy, and through puberty. Exposure to even a minuscule amount of an EDC during one of these windows can permanently alter the architecture of the developing endocrine, reproductive, or neurological systems.

These changes may not manifest as a recognizable health problem until decades later, making it incredibly difficult to draw a straight line from a specific exposure to a later-life diagnosis. This long latency period between cause and effect is one of the most significant hurdles for researchers and regulators.

It complicates epidemiological studies and obscures the true scale of the impact these chemicals have on public health. The symptoms you may be experiencing as an adult could have roots in exposures that occurred long before you were aware of the risks, a reality that underscores the need for a proactive and deeply personalized approach to health.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of endocrine disruption requires a deeper look at the specific scientific principles that make identifying these chemicals so problematic for toxicologists and regulators. The traditional methods for assessing chemical safety were built on a simple premise ∞ “the dose makes the poison.” This principle assumes a linear relationship where a higher dose of a substance produces a greater effect.

Endocrine disruptors, however, operate according to the rules of endocrinology, not classical toxicology. Their behavior is often nonlinear, meaning that low doses can cause significant effects, while higher doses may produce different, or even no, effects. This phenomenon, known as a non-monotonic dose response (NMDR), is a central challenge that invalidates many standard safety testing protocols.

The Flaw in Traditional Toxicology

Standard toxicological testing often involves exposing laboratory animals to high doses of a chemical to identify a No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL). Regulators then apply safety factors to this NOAEL to determine a “safe” level of human exposure. This entire model collapses when dealing with EDCs.

Because EDCs interact with a biological system that is designed to respond to minute concentrations of hormones, they can exert powerful effects at doses far below the NOAEL established in high-dose studies. These low-dose effects are not just a theoretical concern; they have been observed repeatedly in laboratory studies for a wide range of EDCs, including bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and certain pesticides.

The assumption of a linear dose-response relationship, a cornerstone of traditional toxicology, does not apply to many endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

The existence of NMDR curves, which can be U-shaped or inverted U-shaped, means that the most potent effects of an EDC might occur at the very low levels of exposure common in the general population. A high-dose study might completely miss these effects or, worse, incorrectly conclude that the chemical is safe at lower concentrations. This discrepancy between testing models and biological reality is a major source of scientific debate and regulatory delay.

How Do Non-Monotonic Dose Responses Occur?

NMDRs are not mysterious; they arise from the complex way hormones and their mimics interact with biological systems. Several established mechanisms can produce these curves:

- Receptor Downregulation ∞ At high concentrations, an EDC might overwhelm and cause a decrease in the number of available hormone receptors (downregulation), leading to a diminished response. At low doses, this downregulation does not occur, allowing for a stronger relative effect.

- Multiple Receptors ∞ A single EDC may bind to different types of receptors with varying affinities. At low doses, it might activate a high-affinity receptor that triggers one effect, while at higher doses, it also binds to a lower-affinity receptor that initiates a competing or opposing effect.

- Enzyme Induction ∞ High doses of an EDC can induce the production of enzymes that metabolize and clear the chemical from the body, reducing its effect. This metabolic induction is often absent at lower doses.

These mechanisms are well-understood in endocrinology, yet their implications for chemical safety assessment are profound and still not fully integrated into regulatory frameworks.

The Cocktail Effect the Challenge of Mixtures

Another significant scientific challenge is the “cocktail effect.” In the real world, humans are never exposed to a single chemical in isolation. We are constantly exposed to a complex mixture of hundreds of different chemicals from our food, water, air, and consumer products.

Traditional toxicology tests one chemical at a time, a method that fails to account for the combined effects of these mixtures. Research shows that multiple EDCs, even at concentrations that individually produce no observable effect, can act together to cause significant harm.

This can happen in two primary ways:

- Additive Effects ∞ Multiple chemicals that act on the same biological pathway can have their effects add up. For example, exposure to several different xenoestrogens at once can produce a total estrogenic effect that is much greater than the effect of any single chemical.

- Synergistic Effects ∞ In some cases, the combined effect of a mixture is greater than the sum of its parts (1 + 1 = 8). One chemical can enhance the toxicity of another, leading to unpredictable and amplified health consequences.

Studying the toxicology of chemical mixtures is exponentially more complex than studying single chemicals. The sheer number of possible combinations makes comprehensive testing practically impossible. This reality means that our current regulatory system, which is based on single-chemical risk assessments, likely underestimates the true risk posed by our daily environmental exposures.

| Concept | Traditional Toxicology | Endocrine Disruption Science |

|---|---|---|

| Dose-Response | Assumes a monotonic (linear) relationship. “The dose makes the poison.” | Frequently observes non-monotonic (e.g. U-shaped) dose-response curves. |

| Low-Dose Effects | Effects at low doses are predicted by extrapolating from high-dose studies. | Low doses can cause effects not predicted by high doses. |

| Timing of Exposure | Generally considered less critical than the total dose. | Critical windows of development are highly sensitive to disruption. |

| Focus of Study | Often focuses on overt toxicity, like organ damage or cancer. | Focuses on functional changes in hormonal signaling and gene expression. |

| Mixtures | Typically assesses chemicals one at a time. | Recognizes that combined exposures to mixtures are the norm and can have additive or synergistic effects. |

Academic

The scientific frontier in understanding endocrine disruption is moving into the realm of epigenetics. This field provides a mechanistic explanation for how transient environmental exposures, particularly during critical developmental windows, can lead to stable, long-term changes in health and even be passed down through generations.

Epigenetic modifications are chemical tags that attach to DNA and its associated proteins, altering gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence itself. These modifications act as a layer of control, a biological memory that dictates which genes are turned on or off in a particular cell at a particular time. EDCs can hijack this system, leaving a lasting imprint on the epigenome that contributes to disease susceptibility later in life.

Epigenetic Mechanisms of Endocrine Disruption

Several key epigenetic mechanisms are known to be targets of EDCs. These processes work in concert to regulate the chromatin structure and accessibility of genes for transcription.

- DNA Methylation ∞ This is the most studied epigenetic mark. It involves the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base in the DNA sequence, typically at sites called CpG islands located in gene promoter regions. Increased methylation generally leads to gene silencing. EDCs like vinclozolin and BPA have been shown to alter DNA methylation patterns in animal models, affecting genes involved in metabolism, reproduction, and neurodevelopment.

- Histone Modifications ∞ Histones are the proteins around which DNA is wound. Modifications to these proteins ∞ such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation ∞ can either tighten or loosen the chromatin structure. Looser chromatin allows transcription factors to access genes and turn them on, while tighter chromatin keeps them silent. EDCs can interfere with the enzymes that add or remove these histone marks, leading to inappropriate gene activation or silencing.

- Non-Coding RNAs (ncRNAs) ∞ This class of RNA molecules, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), does not code for proteins but plays a critical role in regulating gene expression post-transcriptionally. They can bind to messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, targeting them for degradation or blocking their translation into protein. There is growing evidence that EDCs can alter the expression profiles of ncRNAs, disrupting entire networks of gene regulation.

These epigenetic changes provide a plausible biological mechanism for the delayed effects of EDCs. An exposure in the womb can alter the epigenetic programming of fetal stem cells, creating a latent potential for disease that only emerges in adulthood when triggered by other factors like aging, diet, or further environmental exposures.

Epigenetic modifications induced by endocrine disruptors can serve as a persistent memory of early-life environmental exposures, influencing health trajectories across the lifespan.

The Transgenerational Inheritance of EDC Effects

Perhaps the most profound and unsettling challenge in this field is the evidence for the transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of EDC-induced traits. This concept goes beyond the direct effects on an exposed individual (the F1 generation) or their developing fetus (the F2 generation). Transgenerational effects are those that persist into the F3 generation and beyond, in individuals who were never directly exposed to the initial chemical. This requires the epigenetic marks to be transmitted through the germline (sperm or eggs).

How can this happen? During germ cell development, most epigenetic marks are erased and then re-established in a sex-specific pattern. However, some regions of the genome appear to escape this reprogramming.

If an EDC induces a stable epigenetic change (like an altered DNA methylation pattern) in a primordial germ cell at one of these “escapee” sites, that mark can be passed on to subsequent generations.

Seminal studies using the fungicide vinclozolin have demonstrated that a single exposure during gestation in rats can induce reproductive abnormalities and disease susceptibilities that are transmitted down to the F3 and F4 generations, linked directly to altered DNA methylation patterns in the sperm. This research suggests that the health consequences of our current chemical environment may echo for generations to come.

What Are the Regulatory Implications of Transgenerational Epigenetics?

The possibility of transgenerational inheritance presents an enormous challenge for regulatory science. Current risk assessment models are not equipped to evaluate or quantify risks that span multiple generations. They focus on the health of the individual exposed, not their great-grandchildren.

Proving that a specific chemical is causing transgenerational effects in human populations is nearly impossible given the confounding variables and the immense timescale involved. This scientific complexity creates a state of regulatory paralysis, where the burden of proof is almost insurmountably high, while the potential for widespread, heritable harm continues to grow.

Addressing this will require a fundamental shift in our approach to chemical safety, moving from a reactive, proof-of-harm model to a more precautionary approach that prioritizes the prevention of exposure, especially for vulnerable populations.

| Endocrine Disruptor | Primary Use | Observed Epigenetic Mechanism | Associated Health Outcomes (in animal models) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Plastics, epoxy resins | Altered DNA methylation, histone modification, miRNA expression. | Metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetes), reproductive issues, neurobehavioral changes. |

| Phthalates | Plasticizers, personal care products | Changes in DNA methylation and histone acetylation. | Male reproductive tract abnormalities, reduced testosterone production. |

| Vinclozolin | Fungicide | Transgenerational alterations in sperm DNA methylation. | Prostate disease, kidney disease, immune abnormalities across multiple generations. |

| Dioxins (TCDD) | Industrial byproducts | Persistent changes in DNA methylation via the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR). | Developmental and reproductive toxicity, carcinogenicity. |

References

- Vandenberg, Laura N. et al. “Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals ∞ Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 33, no. 3, 2012, pp. 378-455.

- Gore, Andrea C. et al. “Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals ∞ An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 36, no. 6, 2015, pp. E1-E150.

- Cimmino, I. et al. “Epigenetic Mechanisms of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Obesity.” Biomedicines, vol. 9, no. 11, 2021, p. 1716.

- Fucic, A. et al. “Overview of the effects of chemical mixtures with endocrine disrupting activity in the context of real-life risk simulation ∞ An integrative approach (Review).” Biomedical Reports, vol. 11, no. 5, 2019, pp. 227-234.

- Anway, Matthew D. et al. “Epigenetic Transgenerational Actions of Endocrine Disruptors and Male Fertility.” Science, vol. 308, no. 5727, 2005, pp. 1466-1469.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, Evanthia, et al. “Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals ∞ An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 30, no. 4, 2009, pp. 293-342.

- Walker, Cheryl L. “Minireview ∞ Epigenetic Mechanisms of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals.” Endocrinology, vol. 152, no. 8, 2011, pp. 2843-2849.

- Patisaul, Heather B. and Heather B. Adewale. “Long-Term Effects of Environmental Endocrine Disruptors on Reproductive Physiology and Behavior.” Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, vol. 3, 2009, p. 10.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here illuminates the immense complexity behind identifying and regulating substances that interfere with our most fundamental biological systems. This knowledge is not meant to cause alarm, but to serve as a powerful tool for self-advocacy. Your personal health narrative, the symptoms and feelings you experience daily, is a critical dataset in a world of scientific uncertainty.

Understanding the challenges researchers face validates your experience and shifts the focus from a search for a single external cause to the proactive cultivation of internal resilience. The path forward involves recognizing that your body has an innate capacity for balance.

Supporting its core systems through conscious choices about nutrition, stress management, and targeted clinical protocols becomes the most logical and empowering response. This journey is about moving from a position of passive exposure to one of active, informed stewardship of your own health.