Fundamentals

You have arrived here because you are listening to your body. That feeling ∞ the subtle drag on your energy, the sense that your internal systems are not firing with the precision they once did ∞ is a valid and important signal. It is the beginning of a conversation with your own biology.

In our work, we see this as the first step toward reclaiming a state of function and vitality that is your birthright. The discussion around amino acid supplementation often begins with a focus on muscle growth or recovery, yet this perspective is incomplete.

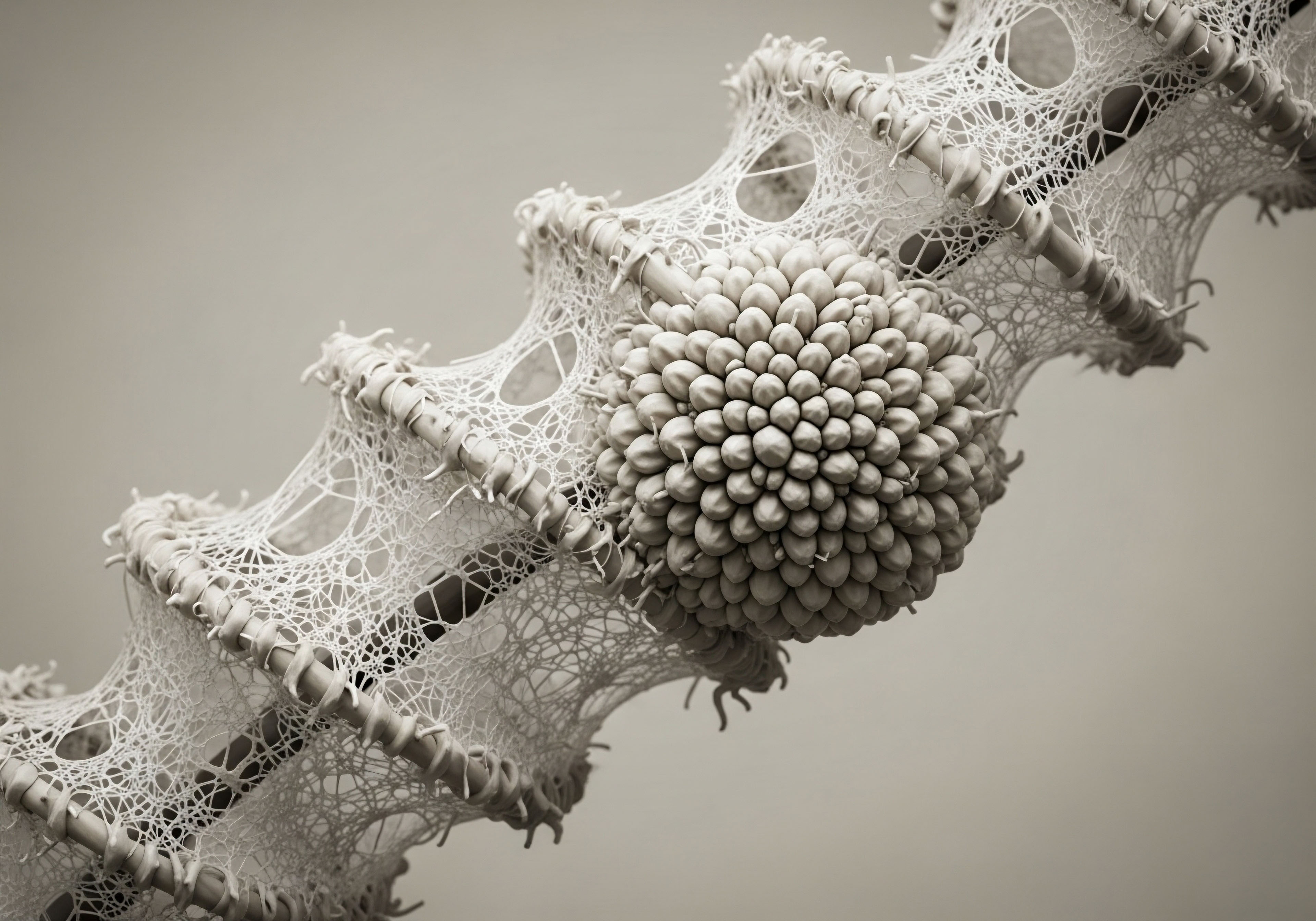

These molecules are far more than simple building blocks; they are potent signaling agents that speak directly to your cells, your glands, and your brain. Understanding their safety is the first principle of using them wisely. It requires a shift in perspective, viewing your body as a complex, interconnected system where every input creates a cascade of effects.

When you introduce a high dose of a single amino acid, you are not just delivering raw material. You are sending a loud, specific command to a system that evolved for balance. The safety of this practice hinges on your body’s capacity to process that command without compromising other critical functions. This capacity is finite. Let us explore the two foundational concepts that govern this delicate biological negotiation ∞ metabolic load and competitive transport.

The Concept of Metabolic Load

Your liver is the master chemical processing plant of your body. When you consume amino acids, whether from a steak or a powdered supplement, they are absorbed and travel directly to the liver. Here, a decision is made ∞ will this amino acid be used to build new tissue, be converted into energy, or be flagged as surplus?

When you supplement with high doses, you risk overwhelming this sophisticated sorting system. The primary safety concern here is the management of nitrogen, a core component of every amino acid.

When an amino acid is broken down for energy, its nitrogen component must be safely removed. The body converts this nitrogen into ammonia, a potent neurotoxin. A healthy liver swiftly neutralizes ammonia by converting it into urea, which is then excreted by the kidneys. Supplementing with excessive amino acids can saturate this pathway.

This forces the liver to work harder and, in susceptible individuals or with prolonged overuse, can lead to an accumulation of ammonia and other metabolic byproducts. One such byproduct is homocysteine, an intermediate metabolite of the essential amino acid methionine. Elevated homocysteine is a well-established marker for inflammation and cardiovascular risk.

Your body has an elegant system for clearing homocysteine, but it requires adequate levels of B-vitamins (B6, B12, and folate). Supplementing with high doses of methionine without ensuring these cofactors are present can disrupt this clearance, creating a molecular problem where none existed before.

The body processes isolated amino acids as powerful metabolic signals, and overloading these pathways can create toxic byproducts that disrupt cellular health.

Understanding Competitive Transport Systems

The second fundamental safety consideration involves a concept of elegant biological competition. Your body uses specialized transport systems to move nutrients from your bloodstream into critical tissues like the brain. Think of these transporters as exclusive doorways, each designed to admit a specific class of molecules.

The large neutral amino acids (LNAAs), a group that includes the popular branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs ∞ leucine, isoleucine, and valine) as well as the precursors to key neurotransmitters (tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine), all compete for passage through the same doorway across the blood-brain barrier.

This is where safety becomes a matter of balance. When you consume a large dose of BCAAs, you effectively flood the entrance to this doorway with a single type of passenger. This surge of BCAAs can competitively inhibit the transport of tryptophan and tyrosine into the brain.

This is not a trivial matter. Tryptophan is the sole precursor to serotonin, the neurotransmitter that governs mood, sleep, and appetite. Tyrosine is the precursor to dopamine, which regulates motivation, focus, and reward. An artificially induced shortage of these precursors can have palpable effects on your mental state and cognitive function.

What begins as a strategy to enhance physical performance could inadvertently compromise your psychological well-being. This principle demonstrates that safety in supplementation is a systemic issue, connecting your muscular goals with your neurological health.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational principles, we can begin to analyze amino acid safety through the precise lens of endocrinology. Your hormonal systems operate on a series of exquisitely sensitive feedback loops. The master control for your reproductive and metabolic hormones resides in the brain, specifically within the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

This axis is a conversation ∞ the hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which tells the pituitary to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones, in turn, signal the gonads (testes or ovaries) to produce testosterone or estrogen. Specific amino acids can directly intervene in this conversation, a reality that carries both therapeutic potential and significant risk if misunderstood.

How Do Amino Acids Influence the Hormonal Axis?

Certain amino acids act as neurotransmitters or signaling molecules within the hypothalamus and pituitary, directly influencing the release of key hormones. This mechanism is the basis for many supplements marketed for hormonal optimization. A clinical understanding requires a look at the evidence for these effects and the body’s adaptive responses.

A Case Study D-Aspartic Acid

D-Aspartic Acid (DAA) is a prime example. It is an amino acid found concentrated in the pituitary gland and testes. Pre-clinical research suggested DAA could stimulate the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus and LH from the pituitary, creating a powerful signal for the testes to produce more testosterone. An early human study appeared to confirm this, showing a significant increase in LH and testosterone after 12 days of DAA supplementation in men with lower baseline testosterone levels.

However, subsequent, more rigorous studies in resistance-trained men with normal or high baseline testosterone levels failed to replicate these findings. Some research even showed that higher doses of DAA (6 grams/day) could decrease testosterone levels. This discrepancy is clinically illuminating.

It suggests that DAA’s effect may be conditional, potentially offering a modest boost to those with suboptimal function but providing no benefit, or even a negative effect, in a system that is already operating at full capacity. The body’s homeostatic mechanisms appear to override the supplemental signal in healthy individuals. This illustrates a critical safety principle ∞ a supplement’s effect is entirely dependent on the internal hormonal environment it encounters.

The BCAA Paradox Insulin Sensitivity

Perhaps the most significant safety consideration for active adults using amino acid supplements is the complex relationship between branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and insulin resistance. While often promoted for muscle growth, chronically elevated levels of BCAAs in the bloodstream are strongly associated with metabolic dysfunction and an increased risk for type 2 diabetes. To understand this paradox, we must examine the role of a specific cellular pathway ∞ the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1).

Leucine, the most potent of the three BCAAs, is a powerful activator of mTORC1. This pathway is a master regulator of cell growth and protein synthesis, which is why BCAA supplementation can support muscle building. Insulin also activates this pathway. The problem arises from chronic overstimulation.

When high levels of leucine constantly activate mTORC1, it can trigger a negative feedback loop that phosphorylates and inhibits Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 (IRS-1). This action effectively dampens the cell’s ability to respond to insulin. The pancreas must then produce more insulin to get the same job done, a condition known as hyperinsulinemia.

This is the very definition of insulin resistance, a foundational state for metabolic disease. Supplementing with high doses of BCAAs, especially outside the context of intense physical activity, may contribute to the very metabolic dysfunction many individuals are trying to avoid.

Chronically supplementing with certain amino acids, like BCAAs, can disrupt insulin signaling pathways, potentially contributing to the development of metabolic resistance.

This highlights the importance of context and dosage. Using BCAAs strategically around a workout, when muscles are highly receptive to both nutrients and insulin, is metabolically different from consuming them throughout the day. The former supports recovery, while the latter may drive pathology.

Comparative Metabolic Effects of BCAAs

While often grouped together, the three BCAAs have distinct metabolic fates and effects. Understanding these differences is key to a more sophisticated approach to supplementation and safety.

| Amino Acid | Primary Metabolic Role | Key Safety Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Leucine | Strongest activator of mTORC1 for muscle protein synthesis. Primarily ketogenic (metabolizes to acetyl-CoA). | Chronic overstimulation of mTORC1 can induce insulin resistance via IRS-1 inhibition. |

| Isoleucine | Both ketogenic and glucogenic (can be converted to glucose). Can improve glucose uptake in muscle tissue independently of insulin. | Less potent mTORC1 activator than leucine, but its metabolites can still contribute to metabolic stress if catabolism is impaired. |

| Valine | Primarily glucogenic. Essential for immune function and central nervous system maintenance. | Its catabolic intermediate, 3-hydroxyisobutyrate (3-HIB), has been shown to promote lipid uptake in muscle, potentially contributing to lipotoxicity and insulin resistance. |

Academic

An academic exploration of amino acid safety requires us to move beyond organ systems and into the molecular machinery of cellular metabolism. The conversation is not merely about whether an amino acid is “good” or “bad,” but how a supraphysiological concentration of a single molecule perturbs an intricate network of metabolic flux, gene expression, and organ-to-organ communication.

The most profound safety considerations are rooted in the disruption of these deeply conserved biological pathways. We will examine two such areas ∞ the integrated regulation of amino acid and glucose metabolism by the liver, and the competitive kinetics at the blood-brain barrier that dictate neurotransmitter synthesis.

Systemic Regulation the Liver’s Glucagon-Amino Acid Axis

For decades, insulin and glucagon have been viewed primarily through the lens of glucose homeostasis. Recent evidence, however, has repositioned glucagon’s primary physiological role as the key regulator of amino acid metabolism. This has profound implications for the safety of amino acid supplementation.

When you ingest a protein-rich meal or an amino acid supplement, the resulting increase in circulating amino acids stimulates pancreatic alpha-cells to secrete glucagon. Glucagon then acts on the liver to upregulate the machinery of amino acid catabolism and ureagenesis, safely disposing of excess nitrogen. It also stimulates gluconeogenesis, using the carbon skeletons from the amino acids to produce glucose.

This creates a delicate feedback loop ∞ amino acids stimulate glucagon, and glucagon promotes the disposal of amino acids. Introducing a massive, isolated bolus of specific amino acids can place significant strain on this axis. For instance, an infusion of amino acids without a corresponding glucose load can lead to a state of hyperglucagonemia.

In an individual with underlying hepatic insulin resistance, this potent glucagon signal can drive excessive hepatic glucose output, worsening hyperglycemia. This reveals a critical safety point ∞ the metabolic effect of an amino acid supplement is inseparable from the background state of the individual’s liver function and insulin sensitivity. The supplement is not acting in a vacuum; it is actively modulating the sensitive interplay between insulin and glucagon, the two master regulators of systemic metabolism.

What Are the Consequences of Impaired Amino Acid Catabolism?

In conditions of metabolic disease, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, the body’s ability to properly catabolize BCAAs is often impaired. This impairment is not uniform across all tissues. While muscle may continue to break down BCAAs, the liver and adipose tissue show reduced oxidative capacity.

This leads to the accumulation of specific toxic metabolites, most notably branched-chain α-ketoacids (BCKAs). These BCKAs, rather than the amino acids themselves, may be the primary drivers of pathology. They have been shown to induce mitochondrial stress, generate reactive oxygen species, and directly impair insulin signaling in multiple cell types.

This leads to a vicious cycle ∞ insulin resistance impairs BCAA catabolism, which leads to the buildup of toxic metabolites, which in turn worsens insulin resistance. Pouring supplemental BCAAs into this already dysfunctional system is metabolically hazardous.

The following table details the key enzymatic steps in BCAA catabolism and the potential consequences of their disruption.

| Metabolic Step | Enzyme Complex | Consequence of Impairment |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 ∞ Reversible Transamination | Branched-Chain Aminotransferase (BCAT) | Converts BCAAs to their corresponding BCKAs. This step is upregulated in the muscle of insulin-resistant individuals. |

| Step 2 ∞ Irreversible Oxidative Decarboxylation | Branched-Chain α-Ketoacid Dehydrogenase (BCKDH) | The rate-limiting step. Its activity is reduced in the liver and adipose tissue in obesity, leading to the accumulation of BCKAs and other toxic downstream metabolites. |

| Downstream Metabolite Accumulation | Various | Build-up of acylcarnitines and specific intermediates like 3-HIB can interfere with mitochondrial function, inhibit fatty acid oxidation, and promote cellular stress. |

Neurochemical Integrity and Blood-Brain Barrier Transport Kinetics

The brain must receive a steady, balanced supply of essential amino acids to function. The primary gatekeeper for this supply is the L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1), a high-affinity transport system located on both the luminal and abluminal membranes of the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

LAT1 has a high affinity for all the large neutral amino acids, creating a scenario of direct competitive inhibition. The rate of transport for any single LNAA is a function of its own concentration in the plasma as well as the concentration of all the other competing amino acids.

This creates a significant and often overlooked safety issue with high-dose BCAA supplementation. A large bolus of BCAAs dramatically increases their plasma concentration, giving them a competitive advantage at the LAT1 transporter. This can significantly reduce the influx of tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine into the brain.

The clinical ramification is a potential depletion of the precursors for serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine synthesis. This phenomenon, known as “central fatigue” in athletic literature, has broader implications for mental health. It could manifest as low mood, anhedonia, poor focus, or disrupted sleep architecture.

For an individual seeking to optimize their well-being, inducing a state of neurotransmitter precursor deficiency is a counterproductive and serious safety concern. The very supplement taken to improve physical performance could be systematically undermining the biochemical foundation of mental and emotional resilience.

High-dose supplementation with a single class of amino acids can competitively block the transport of other essential amino acids into the brain, risking neurotransmitter imbalance.

- Tryptophan Depletion ∞ Reduced transport of tryptophan, the sole precursor for serotonin, can impact mood regulation, satiety signals, and the production of melatonin, which is critical for sleep.

- Catecholamine Depletion ∞ Reduced transport of tyrosine, the precursor for dopamine and norepinephrine, can affect motivation, cognitive sharpness, and the body’s stress response system.

- Phenylalanine Transport ∞ While phenylalanine can be converted to tyrosine, its transport is also subject to the same competitive inhibition, further limiting the substrate pool for catecholamine synthesis.

This detailed understanding reveals that the safest approach to amino acid supplementation is one that respects the body’s intricate transport and metabolic systems. It favors whole proteins or balanced essential amino acid formulas over massive doses of isolated molecules, ensuring that the entire orchestra of amino acids is present, preventing any single instrument from drowning out the others.

References

- Holeček, M. “Side effects of amino acid supplements.” Physiological research, vol. 71, no. S2, 2022, pp. S29-S45.

- Topo, E. et al. “The role and molecular mechanism of D-aspartic acid in the release and synthesis of LH and testosterone in humans and rats.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, vol. 7, no. 1, 2009, p. 120.

- Melville, G. W. et al. “Three and six grams of oral D-aspartic acid supplementation in resistance-trained men.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, vol. 12, no. 1, 2015, p. 15.

- Lynch, C. J. and Adams, S. H. “Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 10, no. 12, 2014, pp. 723-736.

- Pardridge, W. M. “Neutral amino acid transport at the human blood-brain barrier.” Federation proceedings, vol. 45, no. 7, 1986, pp. 2047-2050.

- De Sousa, R. A. L. et al. “The putative effects of D-Aspartic acid on blood testosterone levels ∞ A systematic review.” International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine, vol. 15, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-10.

- Holeček, M. “Glutamine and arginine in hypercatabolic states ∞ is there a rationale for their use as dietary supplements?.” Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, vol. 25, no. 4, 2022, pp. 268-276.

- Wilhelm, F. H. et al. “The Regulation of Glucose and Amino Acid Metabolism by Glucagon.” Journal of the Endocrine Society, vol. 5, no. 7, 2021, p. bvab084.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the complex biological territory you are navigating. It details the intricate signaling pathways, the feedback loops, and the delicate points of balance that define your internal ecosystem. This knowledge is a powerful tool.

It allows you to move from being a passenger in your health journey to becoming an informed collaborator with your own body. The feeling that prompted you to seek this information ∞ the desire for greater vitality, for sharper focus, for a deeper sense of well-being ∞ is the correct instinct. The path forward involves understanding that every choice, especially the decision to introduce a potent biological signal like an amino acid supplement, sends ripples throughout your entire system.

Consider the state of your own unique biology. Are your foundational systems ∞ your hormonal axes, your metabolic health, your stress response ∞ operating with resilience? The answers to these questions form the context in which any therapeutic protocol must be considered. True optimization is a process of restoring coherence to these systems.

It is a meticulous recalibration, guided by data and an understanding of your body’s innate intelligence. The journey is personal, and the most effective strategies are those built upon this deep, individualized understanding.

Glossary

amino acid supplementation

metabolic load

amino acids

with high doses

homocysteine

supplementing with high doses

branched-chain amino acids

large neutral amino acids

amino acid safety

testosterone

testosterone levels

d-aspartic acid

insulin resistance

mtorc1

bcaa

blood-brain barrier

glucagon

amino acid supplement

amino acid catabolism