Fundamentals

Your body is a meticulously organized system of communication. Within this system, peptides function as precise molecular messengers, carrying instructions that govern countless physiological processes. You may have arrived here feeling that this internal communication has been disrupted.

Perhaps you experience persistent fatigue, a decline in vitality, or a sense that your body is no longer functioning with the seamless efficiency it once did. This experience is a valid and important signal. It points toward a need to understand the language of your own biology, to decipher the messages your body is sending, and to learn how specific interventions can help restore clarity to these essential conversations.

Targeted peptide therapies represent a sophisticated method for reintroducing specific, clear instructions into your body’s communication network. These small chains of amino acids are designed to mimic or influence the body’s natural signaling molecules. Their purpose is to support and refine biological functions, from metabolic regulation and tissue repair to hormonal equilibrium.

The desire to use these tools stems from a logical place a proactive intention to reclaim optimal function. It is this very intention that brings us to the complex world of regulation. The framework governing these therapies is built upon a foundational principle protecting public health by ensuring that any therapeutic agent is both safe and effective for its intended use.

The Architecture of Therapeutic Oversight

The primary regulatory body overseeing drugs in the United States is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Its mandate is to evaluate extensive clinical data before a new drug can be marketed to the public.

This process is a multi-stage examination designed to answer critical questions about a substance’s safety profile, its efficacy in treating a specific condition, and the manufacturer’s ability to produce it consistently and without contaminants. A fully FDA-approved drug has successfully completed this rigorous journey, providing clinicians and their patients with a high degree of confidence in its quality and performance. This pathway represents the gold standard for therapeutic validation, forming the bedrock of the pharmaceutical landscape.

Peptide therapies exist within this landscape, and their regulatory status is determined by their history and intended application. Some peptides, like sermorelin, are components of FDA-approved medications. Their use is supported by a deep well of clinical trial data. Many other peptides, however, occupy a different space.

They may be the subject of ongoing research or have a long history of use within specific clinical contexts without having gone through the formal new drug approval process for every potential application. This distinction is the starting point for understanding the regulatory considerations that shape their availability and use. The system is designed to balance the established certainty of approved drugs with the evolving potential of newer therapeutic compounds.

The regulatory framework for peptides is designed to ensure patient safety by categorizing substances based on the strength of their clinical evidence.

What Defines a Drug versus a Biologic?

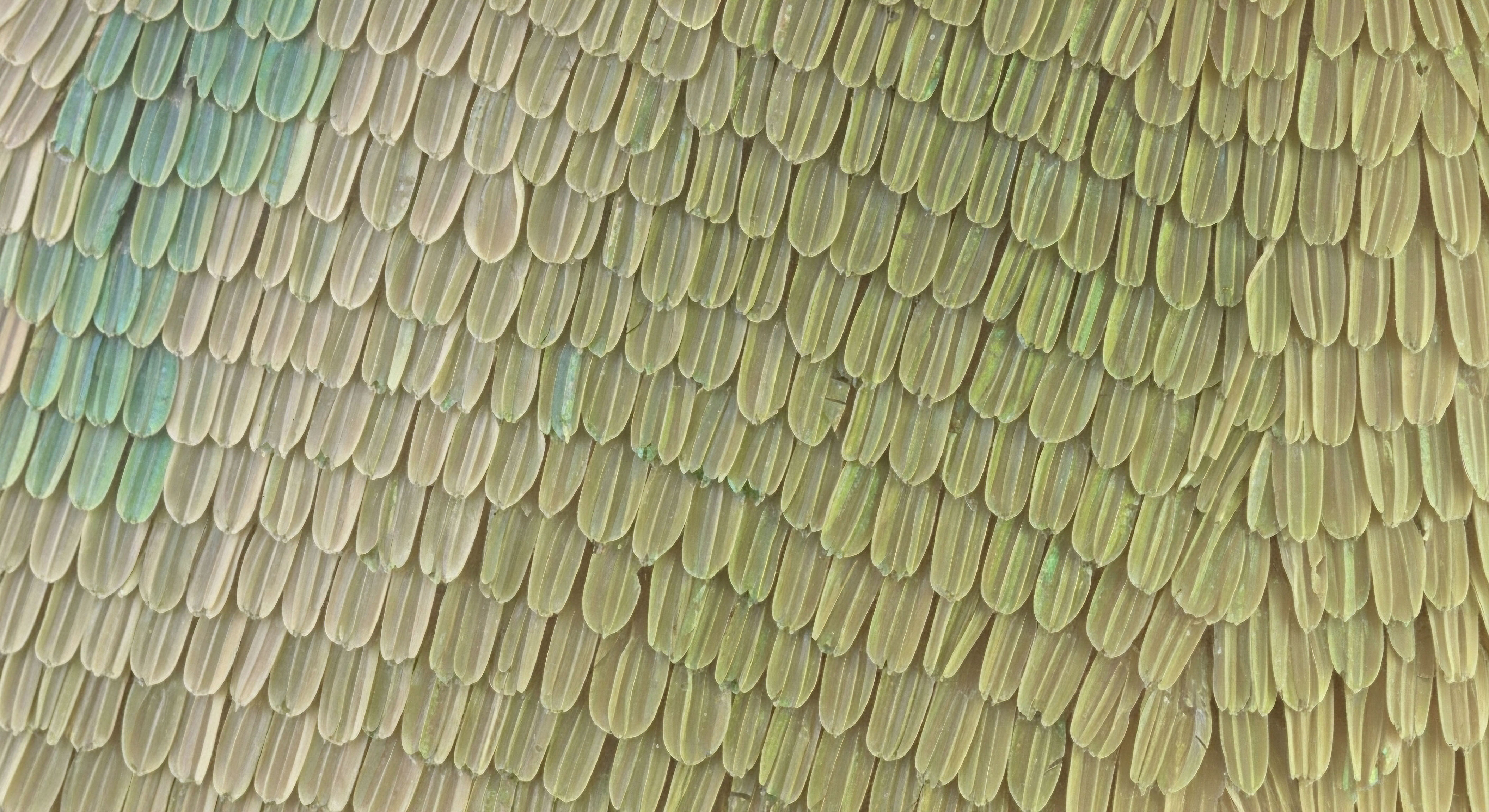

The FDA makes a structural distinction that has significant regulatory consequences. A molecule’s classification is based on its size and complexity. Peptides, defined by the agency as containing 40 or fewer amino acids, are regulated as drugs. This classification places them under a specific set of rules outlined in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act.

Molecules containing more than 40 amino acids are classified as biologics, which are governed by a different and often more stringent set of regulations. This seemingly small distinction in amino acid count creates two separate pathways for development, approval, and compounding. It is a clear line drawn by the agency to manage substances based on their molecular characteristics, and it directly influences how a specific peptide can be sourced and administered in a clinical setting.

This structural definition is central to the entire regulatory conversation. It determines which rules apply and what pathways are available for clinicians seeking to use these therapies for their patients. The journey of a peptide from a laboratory concept to a clinical tool is therefore mapped by its molecular size.

Understanding this foundational classification allows for a clearer comprehension of the subsequent layers of oversight, including the pivotal role of specialized pharmacies and the lists that guide their practices. It is a system of categorization that brings order to a field of immense therapeutic diversity.

Intermediate

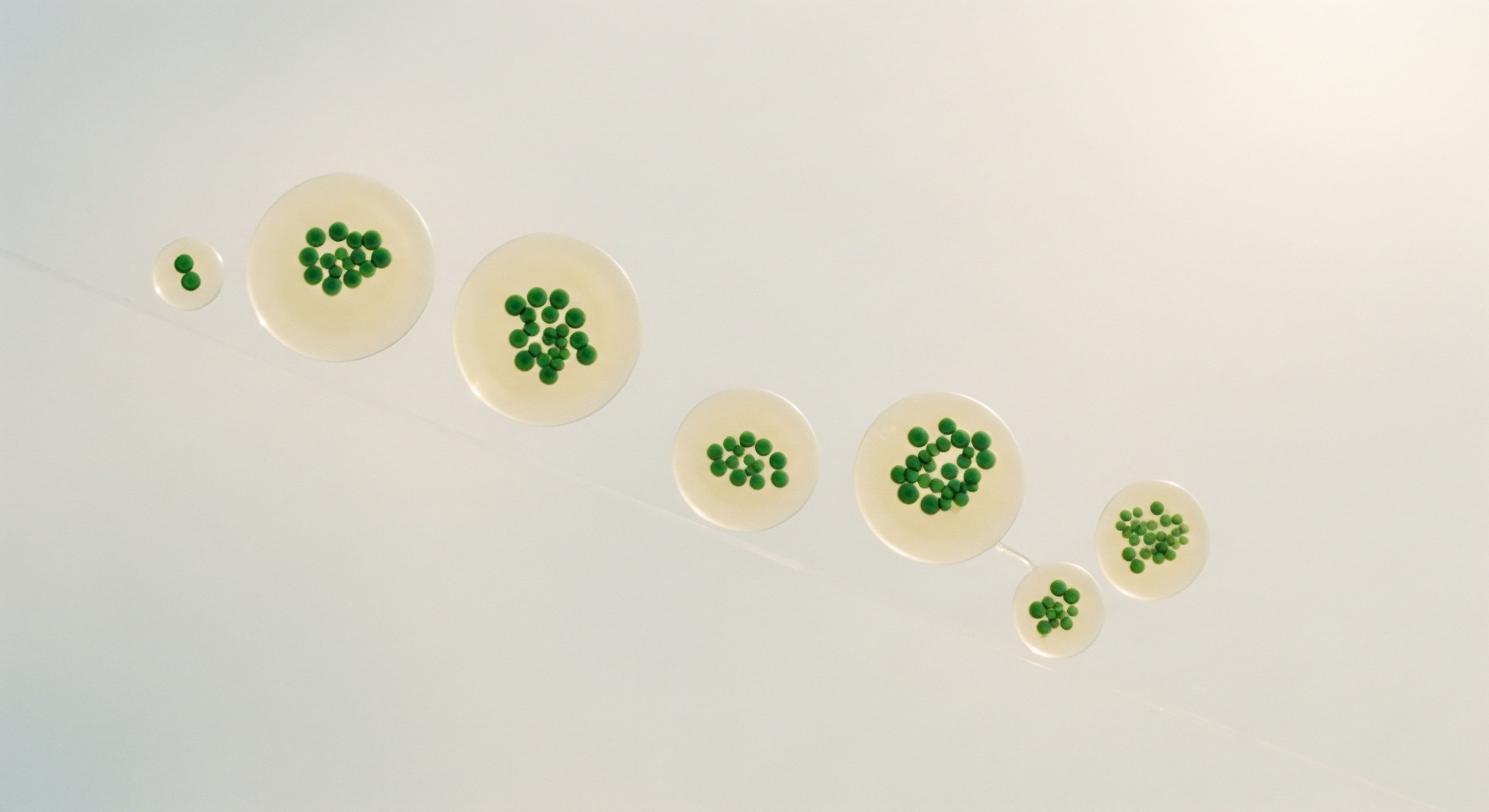

For many individuals, the path to accessing targeted peptide therapies leads through a specialized sector of healthcare known as compounding pharmacies. These are state-licensed facilities authorized to prepare customized medications for individual patients based on a practitioner’s prescription.

The practice of compounding serves a vital role, enabling clinicians to tailor therapies to meet unique patient needs that cannot be met by commercially available, mass-produced drugs. This could involve adjusting a dosage, removing a non-essential ingredient that causes an allergic reaction, or creating a different delivery form, such as a topical cream instead of a pill. This capacity for personalization is what makes compounding pharmacies central to the application of many wellness protocols.

The federal government, through the FD&C Act, provides a framework within which these pharmacies operate, specifically under sections 503A and 503B. Section 503A applies to traditional pharmacies that compound medications for specific patients pursuant to a prescription.

Section 503B governs larger facilities, known as “outsourcing facilities,” that can compound larger batches of sterile drugs without a prescription for each patient, though they are held to a higher standard of federal oversight. The regulations for both types of facilities create exemptions from the full FDA new drug approval process, provided they adhere to strict quality and safety standards. This legal structure is what permits the creation of personalized therapeutic agents, including peptides.

The Role of the 503a Bulks List

A critical component of the regulatory architecture for 503A compounding pharmacies is the “bulks list.” For a pharmacy to legally compound a medication from a bulk drug substance, that substance must meet one of three criteria.

It must be a component of an existing FDA-approved drug, it must be the subject of a United States Pharmacopeia (USP) monograph, or it must appear on a specific list of bulk drug substances that the FDA has determined may be used for compounding.

This list, often referred to as the 503A bulks list, is developed through a rigorous nomination and review process. A substance is nominated for inclusion, and the FDA evaluates it based on factors like its safety profile, the clinical need for its use in compounding, and its history of use.

The status of a peptide on this list directly dictates its availability through compounding pharmacies. In recent years, the FDA has been systematically reviewing nominated substances, leading to significant changes in the regulatory landscape. Some peptides have been placed in a category that permits their use, while others have been assigned to a category that effectively prohibits compounding.

This ongoing review process creates a dynamic environment where the availability of certain peptides can change. It represents the agency’s effort to apply a consistent standard of evidence-based safety to the practice of compounding, ensuring that patient-specific preparations are made from substances with a well-understood risk profile.

Compounding pharmacies operate under specific federal guidelines that permit the creation of personalized medications from approved bulk substances.

How Are Peptides Sourced and Verified?

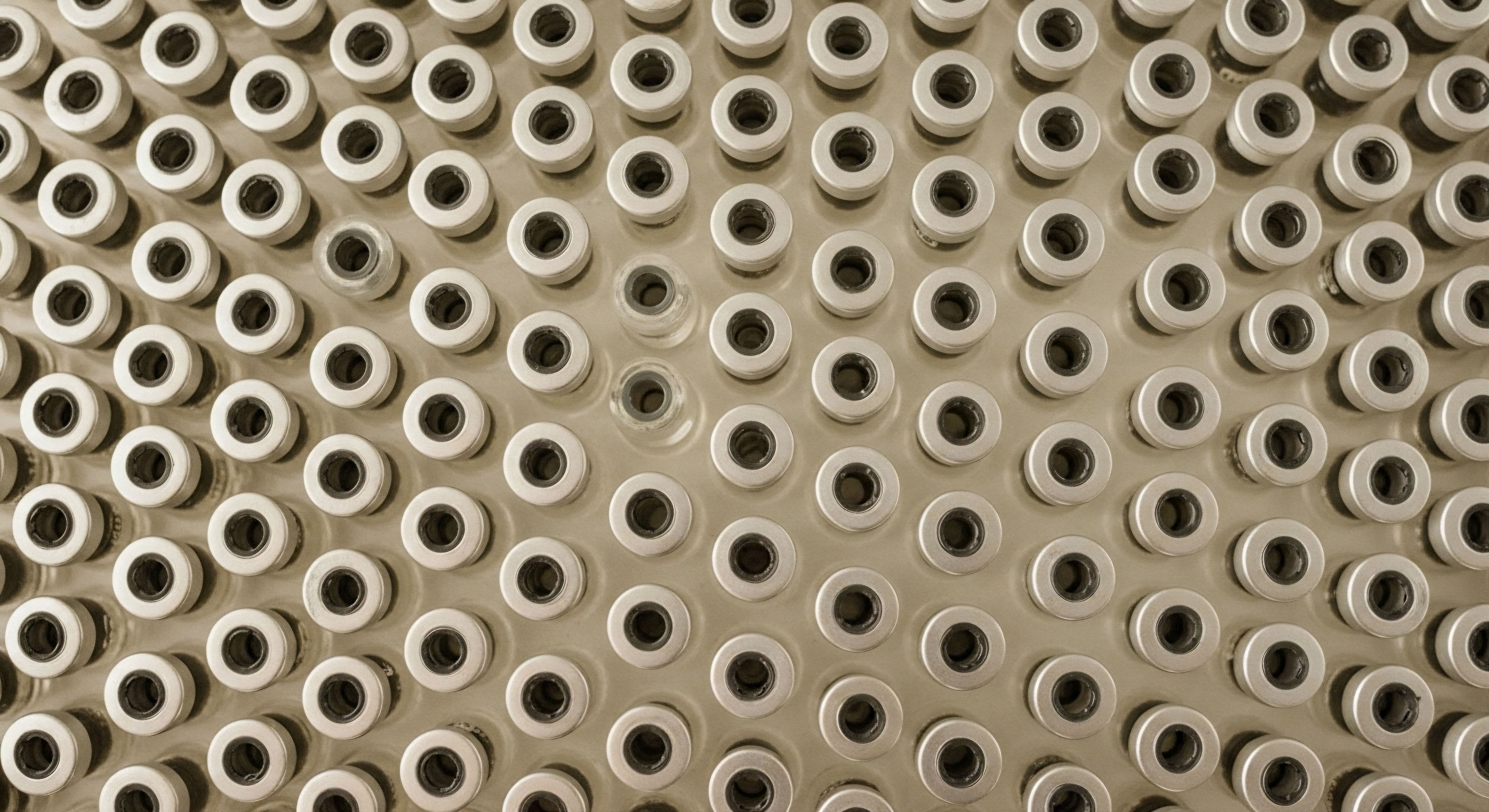

The integrity of any therapeutic agent begins with its source material. For compounding pharmacies, this means sourcing their active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), the bulk peptide powders, from reputable manufacturers. Regulatory guidelines are clear on this point ∞ APIs for human compounding must be of pharmaceutical grade and produced by facilities that are registered with the FDA.

This ensures that the raw materials meet established standards for purity, identity, and quality. A Certificate of Analysis (CoA) from the manufacturer should accompany the API, providing detailed documentation of its testing and verification.

A significant area of regulatory concern involves substances marketed under the label “Research Use Only” (RUO). These materials are not intended for human consumption. They are produced for laboratory research and do not undergo the stringent quality control and safety testing required for pharmaceutical-grade APIs.

The use of RUO materials in compounded preparations for patients is prohibited and represents a serious safety risk. The distinction is absolute. Pharmaceutical-grade APIs are manufactured under strict Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), while RUO materials are not. This bright line is a cornerstone of patient safety within the compounding framework, designed to prevent exposure to potentially contaminated or inaccurately identified substances.

Comparing Regulatory Status of Common Peptides

The regulatory standing of a peptide directly impacts a clinician’s ability to prescribe it through a compounding pharmacy. The following table illustrates the different categories into which peptides may fall, providing a clearer picture of this complex landscape.

| Peptide Example | Regulatory Status | Basis for Compounding Eligibility |

|---|---|---|

| Sermorelin Acetate | Component of an FDA-Approved Drug | Permitted for compounding as it is the active ingredient in Geref, an approved medication. |

| Ipamorelin / CJC-1295 | Not a Component of an FDA-Approved Drug | Eligibility depends on inclusion on the 503A bulks list; status is subject to FDA review. |

| BPC-157 | Not a Component of an FDA-Approved Drug | Recently placed in a category by the FDA that prohibits its use in compounding. |

| Tesamorelin | FDA-Approved Drug (Egrifta SV) | Available as a commercial product; compounding from bulk is generally not performed. |

Academic

The regulatory framework governing peptide therapeutics is a direct reflection of the 20th-century statutes designed to manage conventional small-molecule drugs and, later, large-molecule biologics. Peptides, with their unique intermediate molecular size and functional specificity, occupy a biochemical space that challenges these established dichotomies.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the foundational text of American pharmaceutical law, was architected long before the therapeutic potential of synthetic oligopeptides was fully realized. Consequently, the application of its principles to these agents is an exercise in legal and scientific interpretation, one that reveals the strain points in a system designed for a different era of pharmacology.

The core of the regulatory challenge lies in the definition of “new drugs” and the pathways established for their evaluation. The extensive, multi-phase clinical trial process required for new drug approval is predicated on a one-drug, one-disease model.

It is an exceptionally rigorous and capital-intensive undertaking, designed to produce a high level of statistical certainty regarding the safety and efficacy of a substance for a specific, well-defined indication. This model functions effectively for pharmaceuticals intended to treat millions of patients for a single condition.

Its utility becomes more complex when applied to peptide therapies aimed at optimizing physiological function or addressing subtle systemic imbalances in a highly personalized manner, where the target population is smaller and the therapeutic endpoints are markers of wellness rather than the resolution of overt pathology.

The Compounding Exemption a Legal and Ethical Analysis

The exemptions provided under sections 503A and 503B of the FD&C Act are a legislative acknowledgment that the monolithic new drug approval pathway cannot serve all patient needs. Compounding is sanctioned to fill the therapeutic gaps left by industrial pharmaceutical manufacturing.

This creates a legal channel for patient access to unapproved drugs, predicated on the judgment of a prescribing physician and the skill of a compounding pharmacist. This channel, while essential, exists in a state of perpetual tension with the FDA’s primary mandate of ensuring that all marketed drugs are proven safe and effective.

The agency’s actions in recent years, particularly its systematic review of the 503A bulks list, represent an effort to resolve this tension by applying a more stringent evidentiary standard to the substances used in compounding.

This raises profound questions about what constitutes sufficient evidence for clinical use in the context of personalized medicine. The FDA’s review for the bulks list considers whether there is a “clinical need” for the compounded substance. This assessment often privileges evidence from large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the gold standard for drug approval.

Many peptides, while supported by a body of mechanistic data and smaller-scale clinical studies, lack the extensive RCT data required to meet this high bar. The regulatory process thus creates a deep epistemological challenge ∞ how does a system built on population-level statistics account for therapies designed for the individual’s unique biochemistry?

The exclusion of a peptide from the bulks list is a statement about the perceived insufficiency of its current evidence base, an action that directly curtails its availability for patient-specific applications.

The application of historical drug laws to modern peptide science creates a regulatory friction point, particularly around the evidence required for clinical use.

Navigating the Scientific and Legal Nuances

The scientific and legal considerations for peptide regulation are deeply intertwined. The classification of a peptide as a “drug” versus a “biologic” based on a 40-amino-acid threshold is a prime example of a legal definition shaping scientific and commercial strategy.

A company developing a 39-amino-acid peptide faces a different regulatory pathway than one developing a 41-amino-acid peptide, even if the mechanisms of action are similar. This bright-line rule, while providing regulatory clarity, may not fully capture the biological realities of these complex molecules.

Further complexity arises from the chemical nature of compounded peptides. Peptides are often synthesized using different salt forms, such as acetate or hydrochloride salts, to improve stability and solubility. The FDA has raised concerns that using a different salt form from the one found in an approved drug constitutes the creation of a new, unapproved drug.

This highly technical interpretation has significant implications for compounding pharmacies, requiring them to demonstrate that the specific salt form they use is both safe and clinically justified. This level of scrutiny highlights the agency’s focus on the precise molecular identity of compounded substances, extending its oversight to the subtle chemical modifications that can affect a drug’s performance.

The table below outlines key areas of regulatory focus and the corresponding scientific rationale, illustrating the deep integration of legal standards and biochemical principles.

| Regulatory Consideration | Scientific Rationale and Clinical Implication |

|---|---|

| API Sourcing and Grade | Ensures purity, potency, and absence of endotoxins. Use of non-pharmaceutical grade (e.g. RUO) materials introduces risks of contamination and incorrect dosing. |

| 503A Bulks List Status | Serves as a gatekeeper for compounding eligibility, based on the FDA’s assessment of existing safety and efficacy data for a given peptide. |

| Sterility and Endotoxin Testing | Injectable preparations must be sterile to prevent infection. Endotoxins, which are bacterial byproducts, can cause severe inflammatory reactions if injected. |

| Peptide Salt Form | The choice of salt can affect the compound’s stability, solubility, and bioavailability. Regulators require justification for the specific form used in compounding. |

| Promotional Language and Claims | Clinics and pharmacies are prohibited from making specific disease-treatment claims for unapproved compounded drugs, restricting marketing to general wellness. |

Ultimately, the regulatory environment for targeted peptide therapies is in a state of evolution. It is adapting, sometimes slowly and contentiously, to a class of therapeutics that does not fit neatly into pre-existing categories. The ongoing dialogue between clinicians, researchers, compounding pharmacists, and the FDA will continue to shape the legal contours of this promising field.

The central challenge remains ∞ to construct a regulatory system that both protects patients from unsubstantiated claims and unsafe products while simultaneously allowing for innovation and personalized care. This requires a sophisticated appreciation for the science of peptides and a flexible application of laws written for a different pharmacological world.

References

- Fosgerau, K. & Hoffmann, T. (2015). Peptide therapeutics ∞ current status and future directions. Drug discovery today, 20(1), 122-128.

- Wang, L. Wang, N. Zhang, W. Cheng, X. Yan, Z. Shao, G. Wang, X. Wang, R. & Fu, C. (2022). Therapeutic peptides ∞ current applications and future directions. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 7(1), 48.

- DiPietro, M. & Philo, J. (2021). A Line in the Sand ∞ The FDA’s Final Guidance on the Regulatory Definition of a “Biologic”. The Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI).

- Glass, D. J. (2014). The new and developing therapeutic agents for sarcopenia. Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 99(11), 4006-4017.

- Yan, J. & Wen, H. (2021). Peptides in the clinic. In Peptide and Protein-based Therapeutics (pp. 1-21). Academic Press.

- Hollie, M. (2022). FDA Regulation of Compounded Drugs. Congressional Research Service Report, R47034.

Reflection

You began this exploration seeking to understand the rules that govern a set of powerful biological tools. The knowledge you have gathered about the intricate web of regulations, the distinctions between molecular classifications, and the vital role of compounding pharmacies is more than a collection of facts.

It is the vocabulary you need to engage with your own health journey on a more sophisticated level. This understanding forms a foundation upon which you can ask more precise questions and make more informed decisions in partnership with your clinical guide.

The path toward reclaiming your vitality is a personal one, and it begins with this commitment to comprehending the systems, both biological and regulatory, that shape your options. The true potential lies not in any single molecule, but in your capacity to thoughtfully navigate the path to your own well-being.