Fundamentals

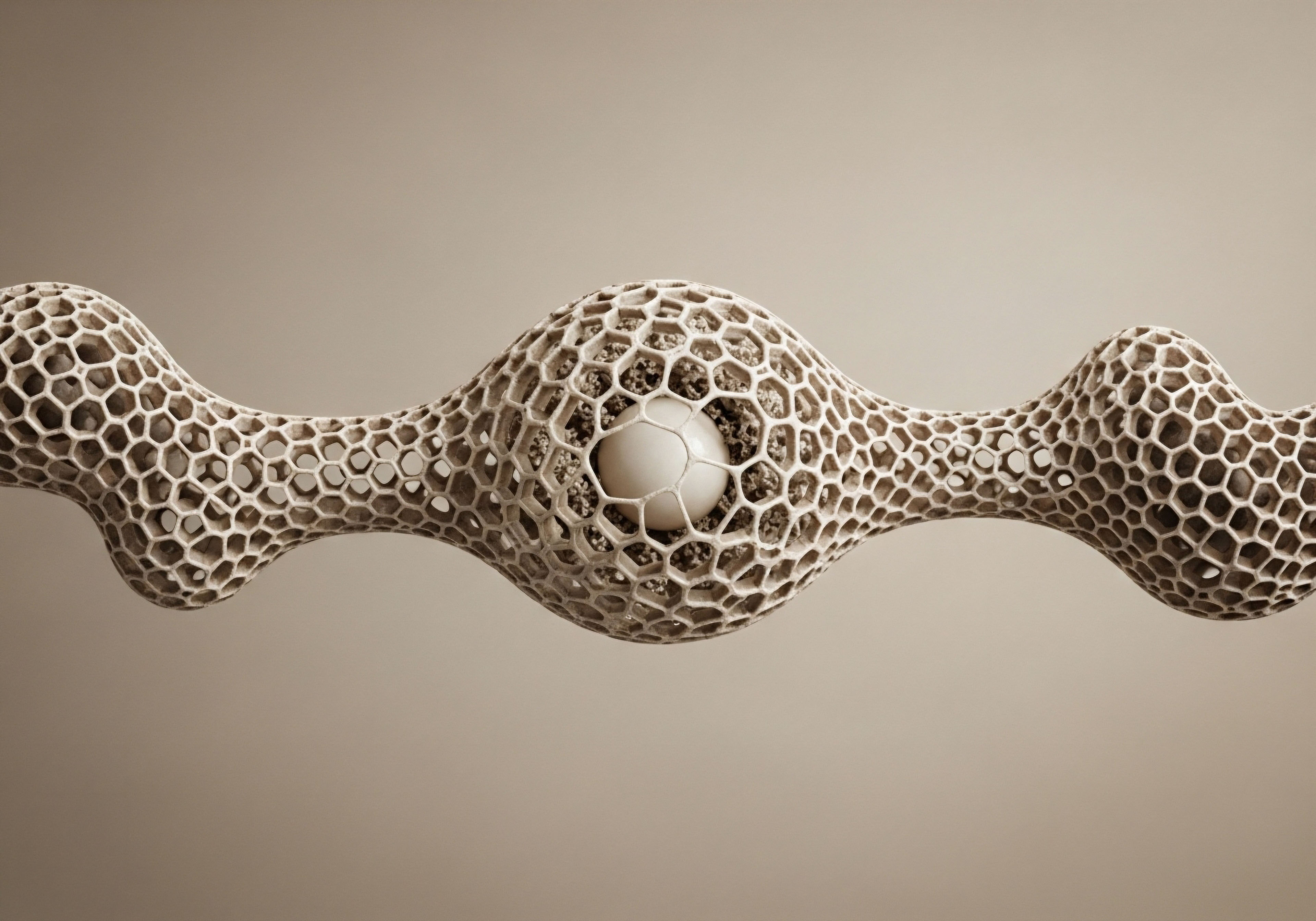

Your body operates as an intricate, responsive network, a system of communication where hormones act as molecular messengers, carrying vital instructions from one tissue to another. When this internal dialogue flows correctly, the result is vitality, stable moods, restorative sleep, and predictable biological rhythms.

The experience of hormonal imbalance, perhaps felt as a subtle shift in energy or a profound disruption in well-being, is a sign that this communication has been compromised. Progesterone is a principal conductor in this orchestra, a stabilizing force whose influence extends far beyond the reproductive system.

Its presence soothes the nervous system, supports thyroid function, and regulates cellular growth throughout the body. Understanding the safety of progesterone therapy begins with a foundational concept ∞ the profound difference between the progesterone your body produces and synthetic molecules designed to mimic some of its actions.

The conversation around hormonal therapy has been shaped, and often complicated, by a history of grouping all progestogenic substances under one umbrella. This generalization obscures a critical distinction. Bioidentical micronized progesterone possesses a molecular structure identical to the hormone produced by the human body.

This identical structure allows it to bind to progesterone receptors with high fidelity, initiating the precise downstream biological signals intended by nature. Synthetic progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), were developed to activate the progesterone receptor but their molecular shape is different.

This altered structure means they can interact with other steroid receptors ∞ like those for androgens or glucocorticoids ∞ initiating unintended biological conversations that are at the root of many safety concerns. The primary safety consideration, therefore, originates at the molecular level. The choice between a bioidentical messenger and a synthetic analogue fundamentally alters the information being delivered to your cells.

A molecule’s structure dictates its function, and in hormonal therapy, this distinction is the bedrock of safety.

The Central Role of Molecular Identity

To truly grasp the safety parameters of progesterone therapy, one must first appreciate its systemic role. In the brain, progesterone is a powerful neurosteroid. It promotes calmness and enhances sleep quality by acting on GABA receptors, the same receptors targeted by anti-anxiety medications. It protects neural tissue and supports cognitive function.

Within the uterus, it prepares the lining for pregnancy and, in its absence, signals menstruation. In breast tissue, it plays a role in healthy cellular differentiation. When therapy is initiated, the goal is to restore these functions by replenishing the body’s natural supply with a molecule it recognizes.

Micronized progesterone facilitates this restoration. The term “micronized” simply refers to a process that reduces the particle size of the hormone, allowing for better absorption when taken orally. This formulation allows the body to receive the same calming, regulating, and protective signals it would from its own endogenous production.

The global perspective on safety is increasingly converging on this point. Regulatory bodies and clinical guidelines are progressively differentiating between the risk profiles of bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins, particularly in the context of long-term health outcomes like cardiovascular wellness and breast health. This shift acknowledges that the most fundamental safety principle is biochemical precision ∞ using the right key for the right lock.

What Are the Initial Considerations for Therapy?

When contemplating progesterone therapy, the initial safety assessment involves a thorough evaluation of your individual health profile and biological needs. The process is a collaborative dialogue between you and a clinician, grounded in both your subjective experience of symptoms and objective laboratory data.

A history of certain conditions, such as specific types of cancer or blood clotting disorders, requires careful consideration and may influence the appropriateness of therapy. The route of administration is another key variable. Progesterone can be delivered orally, transdermally (through the skin), or vaginally.

Each method has a distinct metabolic pathway, influencing its effects and safety profile. Oral micronized progesterone, for instance, is processed by the liver, creating metabolites that contribute to its sedative effects, making it particularly useful for sleep support. Transdermal and vaginal applications largely bypass this first-pass metabolism, delivering progesterone more directly to the bloodstream and tissues.

The safest approach is one that is tailored to your unique physiology and therapeutic goals, ensuring the right dose is delivered via the most appropriate pathway to restore the body’s intended hormonal symphony.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond the foundational principle of molecular identity, a sophisticated understanding of progesterone therapy safety requires an examination of its pharmacokinetics ∞ the journey a substance takes through the body ∞ and the regulatory frameworks that shape its use across different global regions.

The therapeutic experience is profoundly influenced by how progesterone is administered, metabolized, and ultimately utilized by target tissues. These variables are at the heart of clinical decision-making and directly impact the risk-benefit analysis for each individual. The global landscape of hormonal therapy is not uniform; it is a mosaic of differing clinical philosophies, available formulations, and regulatory approvals that dictate how progesterone is prescribed and perceived.

The distinction between systemic and localized effects is paramount. Oral micronized progesterone, for example, undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver. This process generates metabolites like allopregnanolone, a potent neurosteroid that enhances the activity of GABA-A receptors in the brain.

This metabolic pathway is responsible for the calming and sleep-promoting effects often associated with oral administration. While beneficial for many, it also means that a smaller fraction of the parent hormone reaches systemic circulation. In contrast, transdermal or vaginal administration bypasses the liver, resulting in higher systemic progesterone levels relative to the dose administered.

This route is often preferred when the primary goal is to achieve a specific physiological effect in tissues outside the central nervous system, such as providing endometrial protection in women taking estrogen. The safety profile of each route is thus intrinsically linked to its metabolic journey.

A Global Perspective on Formulations and Regulations

The availability and preference for different progestogenic compounds vary significantly across the world, largely influenced by historical clinical practice and the decisions of national regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

In many parts of Europe, particularly France, there has been a long-standing preference for using micronized progesterone, driven by large-scale observational data suggesting a more favorable safety profile. The French E3N cohort study, a significant piece of epidemiological evidence, indicated that the use of micronized progesterone in combination with estrogen was not associated with the same increase in breast cancer risk observed with synthetic progestins.

In the United States, the conversation was heavily shaped by the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, which exclusively used the synthetic progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) in its combined hormone therapy arm. The findings of increased risk for breast cancer and cardiovascular events in that arm led to a broad-stroke caution regarding all progestogens.

Over time, clinical science has dissected these findings, leading to a greater appreciation for the differences among these compounds. This evolving understanding is reflected in the guidelines of major medical societies, which now more clearly distinguish between progesterone and progestins. However, the legacy of the WHI continues to influence prescribing patterns and patient perceptions in North America. This divergence in clinical history has created a varied global landscape where the “standard of care” can differ based on geographical location.

The metabolic pathway of progesterone administration is a key determinant of its therapeutic effects and safety profile.

Comparative Safety Profiles Progesterone Vs Progestins

To make informed decisions, it is essential to compare the documented effects of micronized progesterone against various synthetic progestins on key health markers. The table below synthesizes data from clinical and observational studies, highlighting the differential impacts on cardiovascular and breast health.

| Health Marker | Micronized Progesterone | Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | Norethindrone Acetate (NETA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) |

Generally considered to have a neutral or lower risk profile, especially with transdermal estrogen. |

Associated with an increased risk, particularly when combined with oral estrogens. |

May be associated with an increased risk, though data is less extensive than for MPA. |

| Breast Cancer Risk |

Observational studies suggest a lower risk compared to synthetic progestins, particularly for up to 5 years of use. |

Associated with a statistically significant increase in risk in large-scale trials (WHI). |

Also associated with an increased risk in some observational studies. |

| Lipid Profile |

Tends to have a neutral effect on HDL and LDL cholesterol, preserving the beneficial effects of estrogen. |

Can negatively impact lipid profiles by attenuating the estrogen-induced rise in HDL cholesterol. |

Possesses androgenic properties that can lower HDL cholesterol levels. |

| Mood and Cognition |

Often associated with calming, anxiolytic, and sleep-promoting effects due to its metabolite, allopregnanolone. |

Can be associated with negative mood symptoms, such as irritability or depression, in some individuals. |

Variable effects, with some users reporting androgen-related side effects. |

How Does Administration Route Alter Safety?

The choice of delivery system is a critical safety consideration that allows for the fine-tuning of therapy. Different routes are selected based on the desired therapeutic outcome and the individual’s risk factors.

- Oral Administration ∞ This route is well-studied and approved by regulatory agencies worldwide for endometrial protection. Its primary safety considerations relate to liver metabolism and the potential for dose-dependent drowsiness. It is often dosed at bedtime to leverage this sedative effect.

- Transdermal Administration ∞ Progesterone delivered via a cream or gel bypasses the liver, avoiding the creation of sedative metabolites and allowing for more direct systemic absorption. This can be advantageous for individuals who require endometrial protection without the sedative effects or for those with liver conditions. The main challenge is achieving consistent absorption and adequate systemic levels.

- Vaginal Administration ∞ This route provides high local concentrations in the uterine tissue, making it highly effective for endometrial protection with lower systemic exposure. It is a preferred method in assisted reproductive technologies and is also used for menopausal hormone therapy. It is generally considered very safe with minimal systemic side effects.

Ultimately, navigating the intermediate safety aspects of progesterone therapy involves a multi-layered analysis. It requires an understanding of the molecule itself, its metabolic journey through the body, and the broader clinical and regulatory context in which it is prescribed. This knowledge empowers a more personalized and precise approach to hormonal health, moving beyond generalized warnings to a nuanced appreciation of biochemical individuality.

Academic

An academic exploration of progesterone therapy safety transcends clinical guidelines and enters the realm of molecular biology, receptor pharmacology, and large-scale epidemiology. The central thesis of this advanced analysis is that the safety profile of any progestogenic agent is a direct consequence of its specific interactions with a spectrum of steroid hormone receptors and its subsequent influence on gene transcription.

The divergence in long-term health outcomes between bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins is not an anomaly; it is a predictable result of their distinct molecular structures and resulting pharmacodynamic effects. A deep dive into this topic requires a systems-biology perspective, acknowledging the crosstalk between hormonal signaling pathways and their collective impact on cellular behavior in tissues like the breast, brain, and cardiovascular system.

The foundational difference lies in receptor binding affinity and selectivity. Progesterone binds with high specificity to the progesterone receptor (PR), which exists in two main isoforms, PR-A and PR-B. The balance of signaling through these isoforms mediates progesterone’s effects on cellular proliferation and differentiation.

Synthetic progestins, while designed to target the PR, often exhibit promiscuous binding to other steroid receptors, including the androgen receptor (AR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). This off-target binding is a critical point of divergence. For example, some progestins derived from testosterone, like norethindrone, possess androgenic activity that can negatively affect lipid profiles.

Others, like medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), have been shown to bind to the GR, initiating glucocorticoid-like signaling cascades that can influence cellular processes in ways that native progesterone does not.

The unique transcriptional signature of a progestogenic agent, determined by its receptor binding profile, dictates its ultimate impact on cellular health and long-term risk.

Receptor Pharmacology and Gene Expression

The binding of a hormone to its receptor is only the first step. The subsequent conformational change in the receptor protein dictates which co-activator or co-repressor proteins are recruited, ultimately determining which genes are turned on or off.

Progesterone and MPA, despite both activating the PR, induce different conformational changes, leading to the transcription of different sets of genes. In breast epithelial cells, for instance, progesterone tends to promote differentiation and oppose estrogen-driven proliferation. In contrast, studies have shown that MPA can exert glucocorticoid-like effects that promote the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation and inflammation, potentially contributing to the increased breast cancer risk observed in the WHI trial.

This concept of differential gene expression provides a molecular basis for the epidemiological findings. The table below outlines the varying receptor activities of progesterone compared to a common synthetic progestin, MPA, illustrating the mechanistic foundation for their different safety profiles.

| Receptor Target | Micronized Progesterone (P4) | Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone Receptor (PR) |

High affinity and specificity; balanced PR-A/PR-B activation. |

High affinity; but induces a different receptor conformation and gene expression profile. |

P4 promotes normal differentiation, while MPA may alter cellular growth pathways. |

| Androgen Receptor (AR) |

Has anti-androgenic activity. |

Possesses slight androgenic activity. |

Contributes to differences in effects on skin, hair, and lipid metabolism. |

| Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) |

Weak binding, minimal activity. |

Binds with significant affinity, exerting glucocorticoid-like effects. |

MPA’s GR activity may promote mitogenic and anti-apoptotic effects in breast cells, a key safety concern. |

| Mineralocorticoid Receptor (MR) |

Acts as an antagonist, promoting sodium and water excretion (a natural diuretic effect). |

Lacks this antagonistic effect, may contribute to fluid retention. |

Explains differences in effects on blood pressure and fluid balance. |

What Is the Epidemiological Evidence from Cohort Studies?

While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) like the WHI are considered a high standard of evidence, their findings are specific to the population and compounds studied (in this case, CEE and MPA). Large, long-term prospective cohort studies provide crucial real-world context, especially for comparing different formulations used in clinical practice.

The French E3N study is a landmark in this regard. It followed nearly 100,000 women for many years and was able to analyze risks associated with different types of hormone therapies. Its findings were illuminating ∞ when combined with estrogen, use of synthetic progestins was linked to a significant increase in breast cancer risk.

Conversely, the combination of estrogen with micronized progesterone was not associated with a statistically significant increase in risk. This data provides strong epidemiological support for the hypothesis that the molecular structure of the progestogen is a key determinant of safety.

Further meta-analyses combining results from multiple observational studies have reinforced this conclusion, suggesting that regimens containing micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone (a progestin structurally very similar to progesterone) may be associated with a lower risk of breast cancer compared to other synthetic progestins.

While observational data can be subject to confounding variables, the consistency of these findings across large populations points toward a genuine biological difference. The convergence of molecular science and large-scale epidemiology provides a powerful, evidence-based framework for assessing the safety of progesterone therapy. It underscores that the most critical safety consideration is the selection of a progestogenic agent whose molecular action most closely replicates the natural, protective functions of endogenous progesterone.

Interpreting Conflicting Data and Study Limitations

A rigorous academic analysis also requires acknowledging the limitations and complexities within the scientific literature. No single study is definitive. The WHI, for all its strengths as an RCT, studied an older population, many of whom were years past menopause, and used a specific combination of hormones that is less commonly prescribed today.

Observational studies, while providing valuable real-world data on different formulations, cannot entirely eliminate the possibility of “healthy user bias” or other confounding factors. Therefore, the most robust conclusions are drawn from the totality and convergence of the evidence.

The scientific consensus is moving towards a model of risk stratification based on progestogen type. The primary safety consideration on an academic level is the imperative to translate our understanding of receptor pharmacology and differential gene expression into clinical practice.

This involves a global shift away from treating all progestogens as a single class and toward a precision-based approach that prioritizes bioidentical hormones. This nuanced perspective allows clinicians to optimize hormonal therapy, maximizing benefits while minimizing risks based on the distinct molecular action of the chosen therapeutic agent.

References

- Stanczyk, F. Z. et al. “Progesterone, progestins, and androgens ∞ differential effects on gene expression, cell proliferation, and differentiation in the breast.” Climacteric, vol. 20, no. 3, 2017, pp. 229-235.

- Lobo, R. A. and K. F. L. Gompel. “The role of progestogens in hormonal replacement therapy.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 24, no. 2, 2018, pp. 200-219.

- The NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Editorial Panel. “The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society.” Menopause, vol. 29, no. 7, 2022, pp. 767-794.

- Fournier, A. et al. “Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies ∞ results from the E3N cohort study.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, vol. 107, no. 1, 2008, pp. 103-111.

- Asi, N. et al. “Progesterone vs. synthetic progestins and the risk of breast cancer ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Systematic Reviews, vol. 5, no. 1, 2016, p. 121.

- Situmorang, M. H. et al. “The impact of micronized progesterone on breast cancer risk ∞ a systematic review.” Climacteric, vol. 21, no. 6, 2018, pp. 539-545.

- Rossouw, J. E. et al. “Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women ∞ principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA, vol. 288, no. 3, 2002, pp. 321-333.

- Schindler, A. E. et al. “Classification and pharmacology of progestins.” Maturitas, vol. 61, no. 1-2, 2008, pp. 171-180.

Reflection

You have journeyed from the molecular identity of a hormone to the complex tapestry of global clinical evidence. This knowledge serves as a map, illuminating the biological pathways that influence how you feel and function each day. The purpose of this deep exploration is to transform abstract scientific concepts into a personal understanding of your own internal environment.

The data, the studies, and the molecular mechanics all point toward a single, empowering truth ∞ your body responds with precision to the messages it receives. The path to sustained vitality is paved with informed choices, a clear comprehension of your own physiology, and a collaborative partnership with a guide who can help you interpret your body’s unique signals. The next step is a personal one, a thoughtful consideration of how this knowledge applies to the narrative of your own health.