Fundamentals

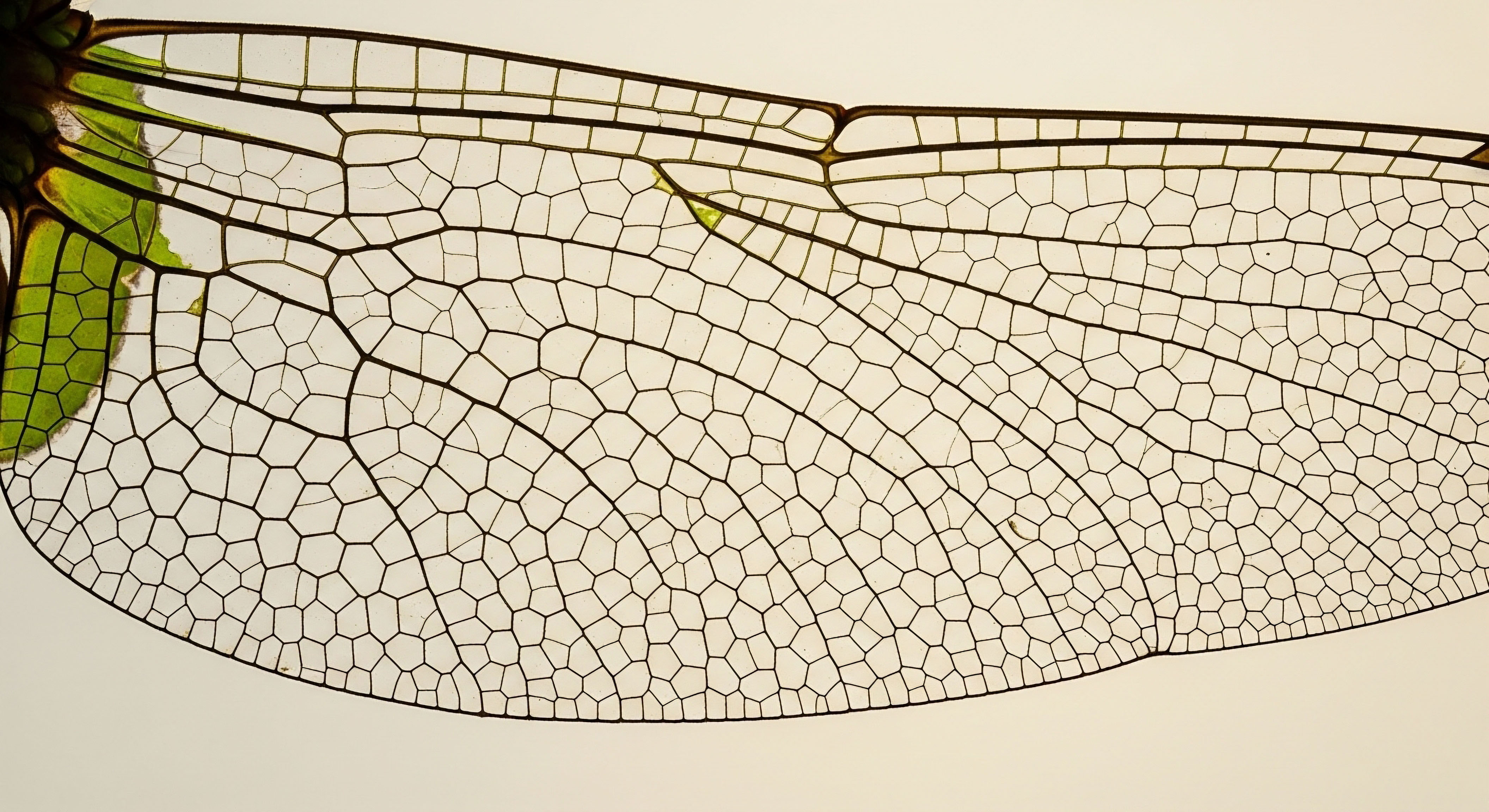

Your body is a finely tuned biological system, an intricate network of communication pathways orchestrated by your endocrine system. Hormones, the chemical messengers of this system, regulate everything from your energy levels and mood to your metabolism and sleep. When we discuss workplace wellness Meaning ∞ Workplace Wellness refers to the structured initiatives and environmental supports implemented within a professional setting to optimize the physical, mental, and social health of employees. programs, we are entering this deeply personal and complex biological space.

A program that fails to honor this complexity, that applies a one-size-fits-all approach to health, is not only destined to be ineffective; it carries substantial legal risks. These legal frameworks exist to protect the very individuality of your biology.

The journey to understanding the legal risks Meaning ∞ Legal risks, within the context of hormonal health and wellness science, refer to potential liabilities or exposures to legal action that may arise from clinical practice, administration of therapies, or provision of health advice. of a poorly designed wellness program A reasonably designed wellness program justifies data collection by translating an individual’s biology into a personalized path to vitality. begins with a foundational concept ∞ a wellness program must be a supportive tool, not a punitive one. It should empower you with knowledge and resources to understand your own body better. When a program becomes coercive, it crosses a line into territory protected by federal law. These laws are not abstract legal concepts; they are safeguards for your health, privacy, and autonomy.

The Legal Bedrock of Employee Health Initiatives

Three principal federal statutes form the foundation of legal compliance for wellness programs. Each one addresses a different facet of your rights as an employee and as an individual navigating your health journey.

The Americans with Disabilities Act Meaning ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), enacted in 1990, is a comprehensive civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities across public life. (ADA) ensures that wellness programs are voluntary and accessible to everyone, regardless of physical or medical conditions. A program that penalizes an employee for not participating in a physically demanding challenge, for example, may violate the ADA if that employee has a disability that prevents them from participating. The law requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations, recognizing that health is not a level playing field.

A wellness program’s design must respect the diversity of human health and ability.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act Meaning ∞ The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) is a federal law preventing discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment. (GINA) protects your genetic information, including your family medical history. A wellness program cannot require you to disclose this information or penalize you for choosing not to. Your genetic blueprint is your own, and GINA ensures that it cannot be used to discriminate against you in the workplace.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) establishes strict privacy and security standards for your protected health information (PHI). Any data collected by a wellness program, from a health risk assessment to biometric screening Meaning ∞ Biometric screening is a standardized health assessment that quantifies specific physiological measurements and physical attributes to evaluate an individual’s current health status and identify potential risks for chronic diseases. results, must be kept confidential. HIPAA ensures that your personal health data is used for your benefit, not against you.

What Makes a Wellness Program Legally Risky?

A poorly designed wellness program Meaning ∞ A Wellness Program represents a structured, proactive intervention designed to support individuals in achieving and maintaining optimal physiological and psychological health states. often exhibits several red flags. Understanding these can help you identify programs that may be crossing legal and ethical lines.

- Coercive Participation ∞ A program is not truly voluntary if there are significant penalties for non-participation. This could include higher insurance premiums, loss of benefits, or other adverse employment actions. The law recognizes that a choice made under duress is not a choice at all.

- One-Size-Fits-All Metrics ∞ Programs that rely on simplistic metrics like Body Mass Index (BMI) to determine rewards or penalties are inherently problematic. BMI does not account for the complex interplay of hormones, genetics, and body composition. Such programs can discriminate against individuals with metabolic conditions or different body types.

- Lack of Confidentiality ∞ Your personal health information is sacrosanct. A program that does not have robust measures in place to protect your data is a major legal risk. This includes how data is collected, stored, and used.

- Absence of Reasonable Accommodations ∞ A program must be designed to be inclusive. This means providing alternative ways for individuals with disabilities to participate and earn rewards. A failure to do so is a clear violation of the ADA.

In essence, the legal risks of a poorly designed wellness program stem from a fundamental disregard for the individual. A program that respects your unique biology, protects your privacy, and offers genuine support is far more likely to be both effective and legally compliant.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational legal principles, we can now examine the more intricate aspects of wellness program design Meaning ∞ Wellness Program Design refers to the systematic development of structured interventions aimed at optimizing physiological function and promoting overall health status. and the specific ways in which they can create legal jeopardy. At this level, we must consider the interplay between different laws and how they apply to the various components of a wellness program, from health risk assessments to biometric screenings and activity-based challenges.

The “Clinical Translator” perspective is vital here, as we connect the legal requirements to the underlying physiological realities of your health journey.

A key area of legal complexity lies in the incentives offered by wellness programs. While incentives can be a powerful motivator, they are also tightly regulated. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Menopause is a data point, not a verdict. (EEOC) have established specific limits on the value of incentives to ensure that programs remain truly voluntary. Crossing these thresholds can transform an incentive into a coercive penalty, triggering legal challenges under the ADA and GINA.

How Do Legal Frameworks Govern Wellness Program Incentives?

The regulations surrounding wellness program incentives are designed to strike a balance. They aim to allow employers to encourage healthy behaviors without creating a situation where employees feel compelled to participate. The rules differ depending on the type of wellness program.

Participatory programs, which do not require an individual to meet a health-related standard to earn a reward, have more flexibility. Examples include attending a seminar or completing a health risk assessment without any requirement for specific results. Health-contingent programs, on the other hand, require individuals to meet a specific health outcome Patient reported outcomes offer a direct, invaluable lens into the real-world impact of hormonal therapies on an individual’s vitality. to earn a reward. These are further divided into two categories:

- Activity-only programs ∞ These require an individual to perform a health-related activity, such as walking a certain number of steps per day. They do not require a specific health outcome.

- Outcome-based programs ∞ These require an individual to achieve a specific health outcome, such as a certain cholesterol level or blood pressure reading.

The structure of a wellness program’s incentives directly impacts its legal standing.

The following table provides a simplified comparison of the key legal requirements for different types of wellness programs, drawing from HIPAA, ADA, and GINA Meaning ∞ GINA stands for the Global Initiative for Asthma, an internationally recognized, evidence-based strategy document developed to guide healthcare professionals in the optimal management and prevention of asthma. regulations.

| Feature | Participatory Programs | Health-Contingent Programs (Activity-Only & Outcome-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Incentive Limit | No limit under HIPAA, but must be considered in the context of ADA’s voluntariness requirement. | Generally limited to 30% of the total cost of employee-only health coverage (or 50% for programs designed to prevent tobacco use). |

| Reasonable Alternative Standard | Not required by HIPAA, but may be necessary as a reasonable accommodation under the ADA. | Required. Must offer an alternative way to earn the reward for individuals for whom it is medically inadvisable or unreasonably difficult to meet the standard. |

| Voluntariness | Participation must be truly voluntary. The size of the incentive must not be so large as to be coercive. | The same voluntariness standard applies. The incentive limits are designed to prevent coercion. |

| Confidentiality | All medical information collected must be kept confidential in accordance with HIPAA and the ADA. | |

The Clinical Collision of Wellness Programs and Personalized Health

The legal risks of poorly designed wellness programs A reasonably designed wellness program justifies data collection by translating an individual’s biology into a personalized path to vitality. are magnified when we consider them through the lens of personalized medicine and endocrinology. A one-size-fits-all wellness program can directly conflict with the nuanced and individualized nature of hormonal health protocols.

Consider a male employee undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). His treatment plan, carefully calibrated by his physician, may lead to changes in body composition, including an increase in muscle mass, which could result in a higher BMI. A wellness program that penalizes him for having a BMI outside a “healthy” range would be not only clinically inappropriate but also potentially discriminatory. It fails to recognize the medical context of his health status and could be challenged under the ADA.

Similarly, a female employee managing perimenopausal symptoms with hormone therapy might experience fluctuations in weight and other biometric markers. A rigid, outcome-based wellness program could penalize her for these fluctuations, which are a direct result of her physiological state and its medical management. This creates a situation where the wellness program is at odds with her prescribed medical care, a clear indicator of a poorly designed and legally vulnerable program.

Designing a Legally and Clinically Sound Wellness Program

To mitigate these risks, a wellness program must be designed with flexibility, inclusivity, and a deep respect for individual biology. Here are some best practices:

- Prioritize Education and Support ∞ A program’s primary focus should be on providing employees with the resources and knowledge to make informed decisions about their health. This could include access to health coaching, educational seminars, and tools for self-monitoring.

- Offer a Variety of Options ∞ Instead of a single, rigid program, offer a menu of options that cater to different interests, abilities, and health statuses. This could include everything from mindfulness and stress management programs to nutrition counseling and fitness challenges with multiple participation levels.

- Ensure Robust Data Privacy ∞ Be transparent about what data is being collected, how it will be used, and who will have access to it. Use a third-party vendor with a proven track record of data security and HIPAA compliance.

- Implement a Clear and Accessible Waiver Process ∞ Have a straightforward process for employees to request a reasonable alternative or a waiver of a particular standard if it is medically inadvisable for them. This is a key requirement of the ADA and HIPAA for health-contingent programs.

Ultimately, a wellness program that is legally sound is one that is also clinically intelligent. It recognizes that health is a personal journey, not a competition, and it provides support and resources that empower individuals to take control of their own well-being.

Academic

An academic exploration of the legal risks associated with corporate wellness programs Meaning ∞ Wellness programs are structured, proactive interventions designed to optimize an individual’s physiological function and mitigate the risk of chronic conditions by addressing modifiable lifestyle determinants of health. reveals a complex and evolving landscape at the intersection of law, medicine, and ethics. The traditional legal analysis, while important, often fails to capture the full scope of the issue.

A more sophisticated understanding emerges when we apply a systems-biology perspective, recognizing the intricate and dynamic nature of human health. This approach illuminates how poorly designed wellness programs can create legal risks that go beyond simple non-compliance with statutory requirements, venturing into the realm of iatrogenic harm and systemic discrimination.

The central thesis of this academic inquiry is that the primary legal risks of poorly designed wellness programs are a direct consequence of their failure to align with the principles of personalized medicine. By imposing uniform standards and metrics on a biologically diverse population, these programs create a clinical-legal dissonance that can lead to significant liability. This dissonance is particularly pronounced in the context of endocrinology and metabolic health, where individual variability is the norm, not the exception.

The Inadequacy of Biometric Uniformity a Medico-Legal Critique

Many corporate wellness programs are built upon a foundation of biometric screening and outcome-based incentives. While seemingly objective, this approach is fraught with peril. The use of simplistic metrics like Body Mass Index Meaning ∞ Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a calculated value relating an individual’s weight to their height, serving as a screening tool to categorize general weight status and assess potential health risks associated with adiposity. (BMI), fasting glucose, and cholesterol levels as determinants of health status is a reductionist approach that ignores the vast complexity of human physiology. From a legal standpoint, this reductionism can give rise to claims of discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Consider the case of an individual with a genetic predisposition to a metabolic disorder. Their baseline biometric markers may fall outside the “ideal” range defined by a wellness program, despite their diligent efforts to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

Penalizing this individual for their genetic makeup is a clear violation of the spirit, if not the letter, of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination GINA ensures your genetic story remains private, allowing you to navigate workplace wellness programs with autonomy and confidence. Act (GINA). The legal and ethical implications are profound, as the program effectively punishes the individual for their biological identity.

A wellness program that ignores the principles of personalized medicine is a program that invites legal challenge.

The following table illustrates the potential for clinical-legal dissonance in common wellness program metrics, highlighting the disconnect between the program’s assumptions and the realities of personalized medicine.

| Biometric Metric | Wellness Program Assumption | Personalized Medicine Reality | Potential Legal Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | A direct and accurate measure of health and body fat. | Fails to distinguish between fat and muscle mass; does not account for hormonal influences on body composition (e.g. TRT, PCOS). | Disparate impact on individuals with certain medical conditions or body types, potentially violating the ADA. |

| Fasting Glucose | A simple indicator of diabetes risk that is solely dependent on lifestyle. | Influenced by a complex interplay of genetics, hormonal factors (e.g. cortisol, growth hormone), and medications. | Discrimination against individuals with pre-diabetes or other metabolic conditions that have a genetic component, raising GINA and ADA concerns. |

| Cholesterol Levels | Primarily determined by diet and exercise. | Significant genetic component; influenced by thyroid function and other hormonal factors. | Penalizing individuals for a health marker that is not entirely within their control, creating potential for ADA and GINA claims. |

The HPG Axis and the Limits of Voluntariness

The concept of “voluntariness” is a cornerstone of wellness program legality. However, a systems-biology perspective challenges the simplistic notion of voluntary choice. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, a critical feedback loop in the endocrine system, profoundly influences mood, motivation, and behavior. An individual with a dysregulated HPG axis, a common occurrence in conditions like andropause and perimenopause, may face significant physiological barriers to making the “healthy choices” promoted by a wellness program.

Forcing such an individual to participate in a program that does not account for their underlying physiological state is not only clinically unsound but also legally questionable. It raises the question of whether participation can be truly voluntary when an individual’s biology is actively working against them. This line of reasoning opens up new avenues for legal challenges, arguing that a program’s failure to accommodate the neurobiological realities of its participants renders it coercive and discriminatory.

Rethinking Wellness Program Design a Call for Clinical and Legal Integration

A truly effective and legally defensible wellness program must be built on a foundation of clinical intelligence and legal foresight. This requires a paradigm shift away from the population-based, one-size-fits-all model and toward a more personalized and adaptive approach.

Future wellness programs should incorporate principles of personalized medicine, using biometric data not as a tool for judgment but as a means of providing individualized feedback and support. They should also be designed in consultation with clinical experts who can ensure that the program’s goals and methods are aligned with current medical understanding.

From a legal perspective, this means moving beyond a compliance-checklist mentality and embracing a more proactive and risk-aware approach. Legal counsel should work closely with clinical experts to design programs that are not only legally compliant on their face but also resilient to the more sophisticated legal challenges that are likely to emerge as our understanding of human biology continues to evolve.

References

- Mujtaba, Bahaudin G. and Frank J. Cavico. “Corporate Wellness Programs ∞ Implementation Challenges in the Modern American Workplace.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management, vol. 1, no. 3, 2013, pp. 193-99.

- Plump, Carolyn M. and David J. Ketchen Jr. “New Legal Pitfalls Surrounding Wellness Programs and Their Implications for Financial Risk.” Business Horizons, vol. 59, no. 3, 2016.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “EEOC’s Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act.” 2016.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Rules.”

- The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-233, 122 Stat. 881.

- Schmidt, Harald, et al. “Carrots, Sticks, and Health Care Reform ∞ Problems with Wellness Incentives.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 362, no. 2, 2010, p. e3.

- Madison, Kristin M. “The Law and Policy of Workplace Wellness Programs.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science, vol. 12, 2016, pp. 119-35.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a framework for understanding the legal and clinical dimensions of workplace wellness. Yet, knowledge is only the first step. The ultimate goal is to apply this understanding to your own unique health journey. Your body tells a story, a complex and personal narrative written in the language of hormones, metabolism, and genetics.

A truly beneficial wellness initiative is one that helps you learn to read that story, to understand its nuances, and to become an active author of your own health.

Consider your own experiences with wellness programs. Have they felt supportive or punitive? Have they respected your individuality or imposed a generic standard? Your answers to these questions are important. They can guide you in advocating for programs that are not only legally sound but also clinically intelligent and deeply human.

The path to optimal health is a personal one. It requires curiosity, self-compassion, and a willingness to look beyond simplistic solutions. The knowledge you have gained is a powerful tool on that path. Use it to ask better questions, to seek out more personalized care, and to build a foundation of health that is uniquely your own.