Fundamentals

Many individuals experience a subtle yet persistent shift in their overall well-being, a feeling that something is simply “off.” Perhaps it manifests as unexplained fatigue, a stubborn resistance to weight management efforts, or a diminished sense of vitality that once felt innate.

These experiences are not merely isolated occurrences; they often represent the body’s profound communication about underlying biochemical shifts. When considering interventions that influence the body’s intricate messaging systems, particularly those involving hormones, a deep understanding of potential outcomes becomes paramount. This exploration centers on the careful calibration of estrogen, a vital signaling molecule, and the considerations that accompany efforts to regulate its activity.

Estrogen, a class of steroid hormones, plays a far broader role than its well-known influence on reproductive health. It acts as a conductor in a vast biological orchestra, influencing bone density, cardiovascular health, cognitive function, mood regulation, and metabolic processes. Its presence, or absence, shapes cellular activity across numerous organ systems.

When estrogen levels deviate from an optimal range, whether too high or too low, the body’s delicate equilibrium can be disrupted, leading to a cascade of symptoms that impact daily life.

Estrogen is a powerful signaling molecule influencing diverse bodily systems, and its careful regulation is vital for overall well-being.

The body possesses sophisticated mechanisms to maintain hormonal balance, a dynamic state of equilibrium. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis serves as a central command center, orchestrating the production and release of hormones, including estrogen. The hypothalamus, located in the brain, releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary gland.

In turn, the pituitary releases luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which then act on the gonads (ovaries in women, testes in men) to produce sex steroids, including estrogen. This intricate feedback loop ensures that hormone levels are adjusted in response to the body’s needs.

When this natural regulatory system encounters challenges, whether due to aging, environmental factors, or specific health conditions, interventions may be considered. These interventions aim to restore balance, but like any powerful tool, they carry inherent considerations. Understanding these considerations requires a look at how estrogen operates at a fundamental level within the body’s complex biological networks.

What Is Estrogen’s Role in the Body?

Estrogen’s influence extends throughout the human body, affecting more than just reproductive tissues. In women, it is primarily produced by the ovaries, with smaller amounts from the adrenal glands and fat tissue. Men also produce estrogen, mainly through the conversion of testosterone by the enzyme aromatase, present in various tissues including fat, brain, and bone.

This hormone contributes to the maintenance of bone mineral density, protecting against conditions like osteoporosis. It also plays a part in cardiovascular health, influencing cholesterol levels and blood vessel function.

Beyond these physical aspects, estrogen impacts neurological function, affecting mood, sleep patterns, and cognitive clarity. Its presence helps regulate the body’s metabolic rate and the distribution of fat. A healthy estrogen balance supports skin elasticity, hair quality, and overall tissue integrity. When this balance is disturbed, symptoms can range from subtle shifts in energy to more pronounced changes in physical and mental well-being.

How Does Hormonal Balance Shift over Time?

The body’s hormonal landscape is not static; it undergoes continuous adaptation throughout life. For women, significant shifts occur during puberty, reproductive years, perimenopause, and postmenopause. During perimenopause, ovarian function gradually declines, leading to fluctuating and eventually decreasing estrogen levels. This transition can bring about symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, sleep disturbances, and mood variations.

Men also experience age-related hormonal changes, often referred to as andropause, characterized by a gradual decline in testosterone production. This decline can indirectly affect estrogen levels, as less testosterone is available for conversion via aromatase. These natural shifts underscore the dynamic nature of the endocrine system and the body’s continuous effort to adapt, sometimes requiring support to maintain optimal function.

Intermediate

When the body’s innate mechanisms for estrogen regulation falter, clinical protocols may be considered to restore physiological balance. These interventions are not one-size-fits-all solutions; rather, they represent a careful calibration of biochemical recalibration, designed to address specific imbalances while minimizing potential considerations. Understanding the ‘how’ and ‘why’ behind these therapeutic agents is vital for anyone considering such support.

Hormonal optimization protocols often involve the administration of exogenous hormones or compounds that modulate endogenous hormone production or action. The aim is to bring estrogen levels into a range that supports vitality and mitigates symptoms, much like adjusting a thermostat to maintain a comfortable internal environment. This requires a precise understanding of the individual’s unique biochemical profile and symptomatic presentation.

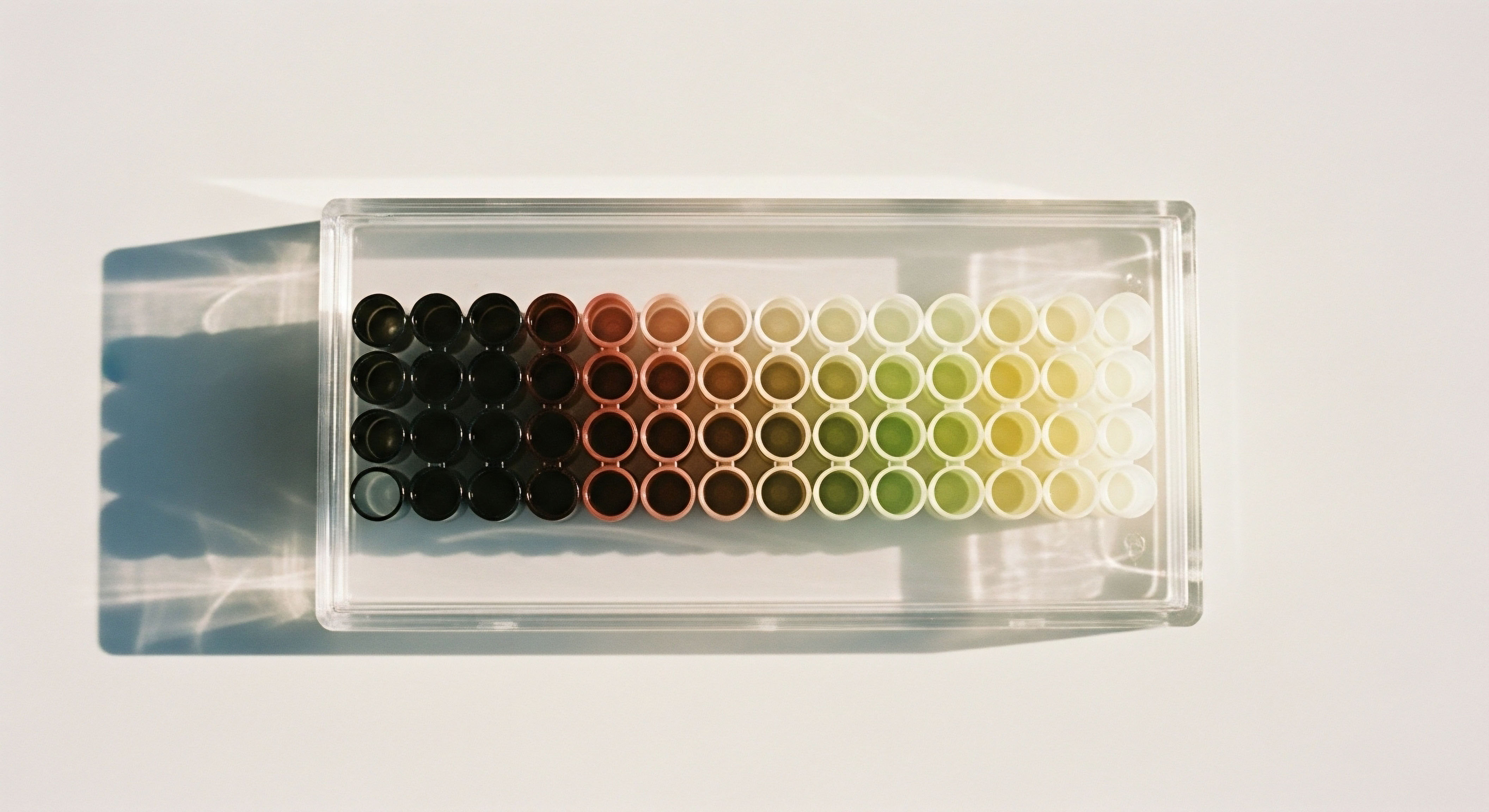

Hormonal optimization protocols aim to restore physiological balance through precise biochemical recalibration.

What Are the Risks of Estrogen Excess?

An excess of estrogen, often termed estrogen dominance, can present its own set of considerations, impacting both men and women. In women, this can manifest as increased breast tenderness, fibrocystic breasts, heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding, and heightened premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms. It may also contribute to conditions such as uterine fibroids and endometriosis. For men, elevated estrogen levels, often resulting from excessive testosterone conversion, can lead to gynecomastia (breast tissue development), fluid retention, and a reduction in libido.

Beyond these symptomatic presentations, chronically elevated estrogen levels have been associated with more significant health considerations. These include an increased propensity for blood clot formation, which carries risks of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). There is also a recognized association with an elevated risk of certain hormone-sensitive cancers, such as endometrial cancer in women with an intact uterus, and some forms of breast cancer.

The mechanisms behind these risks involve estrogen’s proliferative effects on various tissues. When estrogen stimulation is unopposed by other hormones like progesterone, or when its levels are consistently high, it can promote cellular growth that, in susceptible individuals, may become dysregulated. This underscores the importance of a balanced approach to estrogen regulation, ensuring that interventions do not inadvertently create an environment of excess.

What Are the Risks of Estrogen Deficiency?

Conversely, insufficient estrogen levels also present a range of considerations that significantly impact quality of life and long-term health. For women, the decline in estrogen during perimenopause and postmenopause is directly linked to vasomotor symptoms like hot flashes and night sweats, as well as vaginal dryness and discomfort, collectively known as genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Reduced estrogen also contributes to diminished bone mineral density, increasing the risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

Beyond these physical manifestations, low estrogen can affect cognitive function, leading to brain fog or memory lapses, and contribute to mood disturbances, including anxiety and depressive states. Cardiovascular health is also influenced, as estrogen plays a protective role in maintaining arterial elasticity and healthy lipid profiles. In men, while less common, estrogen deficiency can also impact bone health and contribute to cardiovascular concerns.

The physiological basis for these symptoms lies in estrogen’s widespread receptor distribution throughout the body. When these receptors are inadequately stimulated, the tissues and systems they govern cannot function optimally. This highlights the delicate balance required; while excess estrogen carries risks, so too does its deficiency, necessitating a thoughtful approach to its regulation.

How Do Aromatase Inhibitors Influence Estrogen?

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) represent a class of medications designed to reduce estrogen levels by blocking the action of the aromatase enzyme, which converts androgens into estrogens. These agents are primarily utilized in the management of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women, where reducing estrogen can slow cancer growth.

In male hormone optimization protocols, a low dose of an AI like Anastrozole (typically 2x/week oral tablet) may be included to manage the conversion of exogenous testosterone into estrogen, preventing symptoms of estrogen excess such as gynecomastia or fluid retention.

While effective in lowering estrogen, AIs carry their own set of considerations. The most commonly reported side effects include joint and muscle pain, often referred to as aromatase inhibitor musculoskeletal syndrome (AIMSS). This discomfort can range from mild aches to significant pain, sometimes leading to treatment discontinuation. Other considerations include:

- Bone Mineral Density Loss ∞ By significantly reducing estrogen, AIs can accelerate bone loss, increasing the risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

- Hot Flashes and Night Sweats ∞ These vasomotor symptoms can intensify due to the profound reduction in estrogen.

- Vaginal Dryness ∞ A direct consequence of estrogen depletion, impacting comfort and sexual health.

- Lipid Profile Changes ∞ Some individuals may experience unfavorable shifts in cholesterol levels.

- Fatigue ∞ A general sense of tiredness can also be a reported side effect.

The management of these considerations often involves supportive therapies, lifestyle adjustments, or dose modifications. For instance, addressing bone density requires careful monitoring and potentially calcium, vitamin D, or bisphosphonate supplementation. The decision to use an AI, particularly in male hormone optimization, involves a careful assessment of the individual’s baseline estrogen levels, symptoms, and overall health profile.

What Are the Considerations with Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators?

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) are another class of compounds that interact with estrogen receptors, but their action is tissue-specific. This means they can act as an estrogen agonist (mimicking estrogen’s effects) in some tissues while acting as an antagonist (blocking estrogen’s effects) in others.

This selective action makes them valuable in various clinical scenarios. For instance, Tamoxifen is widely used in breast cancer treatment, acting as an estrogen antagonist in breast tissue. Conversely, it acts as an estrogen agonist in bone and uterine tissue.

In male fertility-stimulating protocols, Clomid (clomiphene citrate), a SERM, is used to stimulate the pituitary gland to release more LH and FSH, thereby increasing endogenous testosterone production. This indirect effect can also influence estrogen levels, as more testosterone becomes available for aromatization.

Despite their targeted action, SERMs are not without considerations. Common side effects can include hot flashes and vaginal dryness, particularly with agents that have antagonistic effects in certain tissues. More significant considerations, especially with long-term use of certain SERMs like Tamoxifen, include:

- Increased Risk of Blood Clots ∞ This is a recognized consideration, particularly with oral SERMs, due to their estrogenic effects on clotting factors.

- Endometrial Hyperplasia or Cancer ∞ For SERMs that act as agonists in the uterus (like Tamoxifen), there is an increased risk of endometrial thickening or, in rare cases, endometrial cancer.

- Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS) ∞ While rare, Clomid can lead to OHSS in women undergoing fertility treatments, characterized by enlarged ovaries and fluid shifts.

The careful selection of a SERM, considering its specific tissue effects and the individual’s health profile, is paramount. Regular monitoring is essential to detect and manage any potential considerations early.

How Do Peptides Affect Hormonal Balance?

Peptide therapies, while not directly regulating estrogen, can indirectly influence hormonal balance through their effects on the broader endocrine system. For example, Gonadorelin, a synthetic form of GnRH, is used in male hormone optimization protocols (2x/week subcutaneous injections) to stimulate the pituitary to produce LH and FSH. This helps maintain natural testosterone production and fertility, which in turn influences the substrate available for estrogen synthesis.

Other peptides, such as Sermorelin, Ipamorelin/CJC-1295, and MK-677, are growth hormone-releasing peptides (GHRPs) or growth hormone secretagogues. While their primary action is to stimulate growth hormone release, growth hormone itself interacts with various metabolic pathways that can indirectly influence hormonal sensitivity and overall endocrine function. Improved metabolic health and body composition, often seen with these peptides, can contribute to a more balanced hormonal environment.

The considerations with peptide therapies are generally fewer and milder compared to direct hormonal interventions, but they are not absent. These can include injection site reactions, transient headaches, or mild fluid retention. The indirect nature of their influence on estrogen means that their impact on estrogen regulation risks is less direct, but their role in supporting overall endocrine health is significant.

| Intervention Type | Primary Mechanism | Common Considerations | Significant Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatase Inhibitors (AIs) | Block androgen-to-estrogen conversion | Joint/muscle pain, hot flashes, vaginal dryness | Bone mineral density loss, lipid changes |

| Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) | Tissue-specific estrogen receptor modulation | Hot flashes, vaginal dryness | Blood clots, endometrial hyperplasia/cancer (Tamoxifen) |

| Exogenous Estrogen (HRT) | Direct estrogen replacement | Breast tenderness, fluid retention, headaches | Blood clots, stroke, certain cancers (dose/route dependent) |

| Gonadorelin (Peptide) | Stimulates pituitary LH/FSH release | Injection site reactions, transient headaches | Rarely, pituitary desensitization with improper use |

Academic

The human endocrine system operates as a deeply interconnected network, where the regulation of one hormonal pathway inevitably influences others. When considering interventions aimed at estrogen regulation, a systems-biology perspective becomes indispensable. This approach moves beyond isolated hormone levels, examining the intricate feedback loops, metabolic pathways, and cellular signaling cascades that collectively determine an individual’s physiological state.

The potential considerations associated with estrogen regulation interventions are best understood through this lens, recognizing that modifying one component can ripple throughout the entire system.

Estrogen’s biological actions are mediated through its binding to specific receptors ∞ estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ). These receptors are widely distributed across various tissues, including reproductive organs, bone, brain, cardiovascular system, and adipose tissue. The differential expression and activation of these receptor subtypes explain estrogen’s diverse and sometimes opposing effects in different tissues.

For instance, ERα is highly expressed in the uterus and breast, mediating proliferative effects, while ERβ is more prevalent in the brain and bone, often associated with protective or anti-proliferative actions.

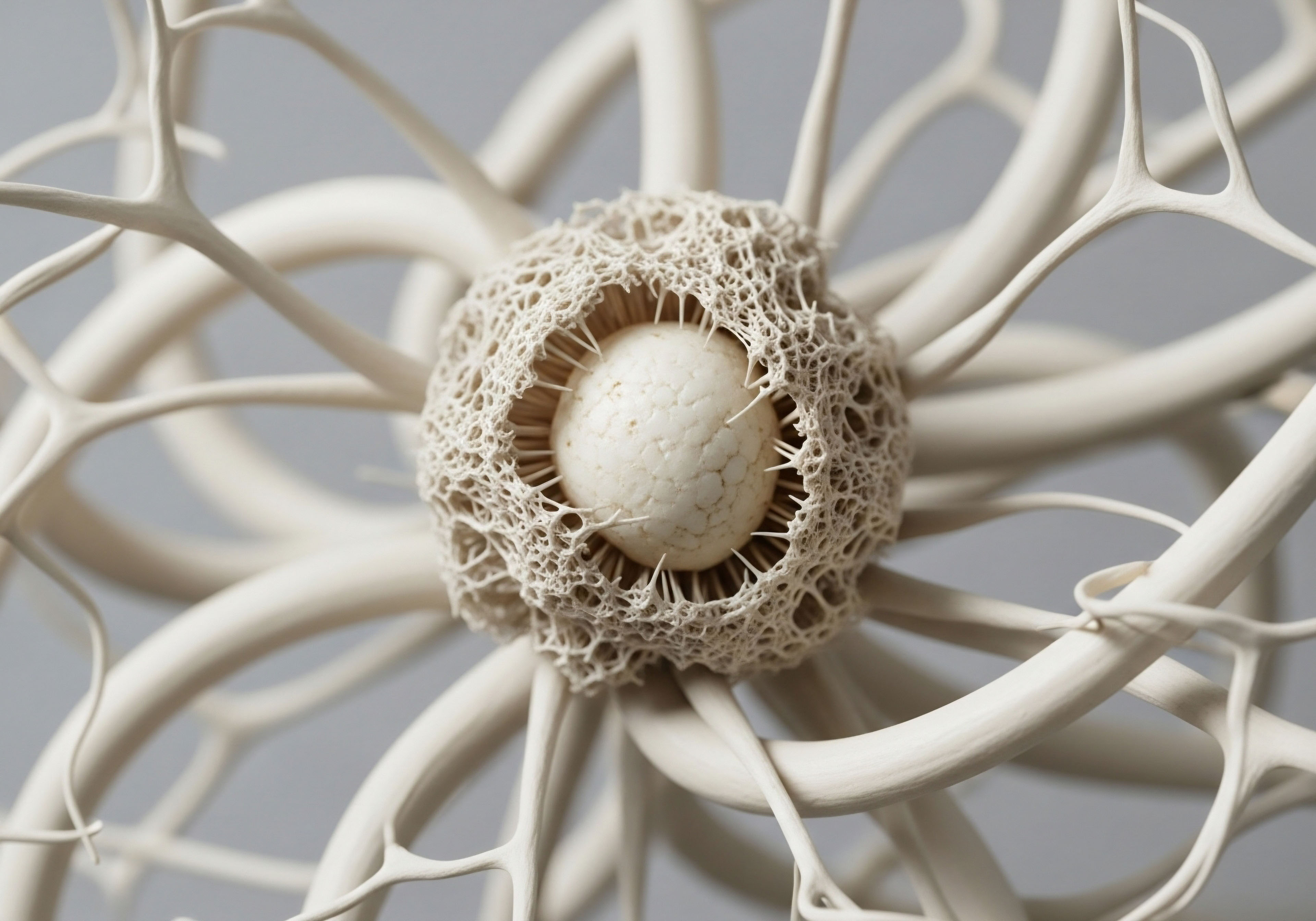

Estrogen regulation interventions impact a complex web of biological systems, necessitating a holistic, systems-biology approach.

How Do Estrogen Interventions Affect Cardiovascular Health?

Estrogen plays a significant role in maintaining cardiovascular integrity. It influences endothelial function, lipid metabolism, and inflammatory processes. However, the relationship between estrogen regulation interventions and cardiovascular outcomes is complex and has been a subject of extensive clinical investigation. Early observational studies suggested a protective effect of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on cardiovascular disease, but large randomized controlled trials, such as the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), presented a more nuanced picture.

The WHI study indicated an increased risk of cardiovascular events, including coronary heart disease and stroke, in older postmenopausal women initiating combined estrogen-progestin therapy. This finding challenged previous assumptions and underscored the importance of timing and individual risk factors.

Subsequent analyses have suggested that the “window of opportunity” hypothesis may be relevant, implying that HRT initiated closer to the onset of menopause (typically under 60 years of age or within 10 years of menopause) may confer cardiovascular benefits or be neutral, while initiation in older women or those further from menopause may carry increased risks.

The route of estrogen administration also appears to influence cardiovascular considerations. Transdermal estrogen, absorbed through the skin, bypasses first-pass liver metabolism, potentially leading to a lower risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke compared to oral estrogen. Oral estrogen can increase the production of clotting factors and inflammatory markers in the liver, contributing to a pro-thrombotic state. Therefore, the choice of intervention and its delivery method must be carefully weighed against an individual’s cardiovascular risk profile.

What Are the Oncological Considerations of Estrogen Regulation?

The relationship between estrogen and certain cancers, particularly breast and endometrial cancers, is a critical area of consideration for estrogen regulation interventions. Estrogen’s role as a growth factor for hormone-sensitive tissues means that its dysregulation can influence oncogenesis.

For breast cancer, combined estrogen-progestin therapy has been associated with a small but statistically significant increase in risk, particularly with longer durations of use (typically beyond 3-5 years). Estrogen-only therapy, used in women who have had a hysterectomy, appears to carry little or no increased risk of breast cancer.

The mechanism involves estrogen’s proliferative effects on mammary epithelial cells, potentially promoting the growth of existing microscopic tumors or initiating new ones in susceptible individuals. The risk typically declines after discontinuation of therapy.

In the context of endometrial cancer, unopposed estrogen therapy (estrogen without a progestin) significantly increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. Progestins are therefore essential for women with an intact uterus receiving estrogen, as they counteract estrogen’s proliferative effects on the endometrium, reducing this risk to a level similar to that of non-users.

Aromatase inhibitors, by profoundly lowering estrogen levels, are a cornerstone in the treatment of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. However, their mechanism of action, which involves severe estrogen deprivation, contributes to side effects such as bone loss and musculoskeletal pain, as discussed previously. SERMs, with their mixed agonist/antagonist properties, present a different oncological profile. Tamoxifen, for example, reduces breast cancer risk but increases the risk of endometrial cancer due to its agonistic effect on uterine tissue.

The decision to intervene with estrogen regulation must therefore involve a thorough assessment of personal and family history of cancer, genetic predispositions, and ongoing surveillance.

How Do Estrogen Interventions Impact Bone and Metabolic Health?

Estrogen is a primary regulator of bone remodeling, promoting bone formation and inhibiting bone resorption. Estrogen deficiency, such as that occurring after menopause, leads to accelerated bone loss and increased risk of osteoporosis. Hormone replacement therapy with estrogen is highly effective in preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

However, interventions that suppress estrogen, such as aromatase inhibitors, can have detrimental effects on bone health. These agents induce a state of severe estrogen deprivation, leading to rapid bone mineral density loss and a significantly increased risk of fractures. This necessitates proactive strategies, including bone density monitoring (e.g. DEXA scans), calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and potentially bisphosphonate therapy, to mitigate this consideration.

Metabolic health is another domain significantly influenced by estrogen. Estrogen affects glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, and fat distribution. Low estrogen levels are associated with increased visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, and a less favorable lipid profile. While HRT can positively influence these metabolic markers, the overall impact on metabolic syndrome and diabetes risk is complex and depends on various factors, including the type of estrogen, route of administration, and individual metabolic status.

The interplay between estrogen, metabolic function, and inflammation is a dynamic area of research. Dysregulated estrogen signaling can contribute to chronic low-grade inflammation, which is a driver of many age-related conditions. Therefore, optimizing estrogen levels, whether through replacement or modulation, can have broad implications for metabolic resilience and systemic inflammation.

What Are the Long-Term Implications of Estrogen Modulation on Cognitive Function?

| System Affected | Estrogen Deficiency Risks | Estrogen Excess Risks | Intervention-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular System | Increased atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia | Increased thrombosis, stroke (oral HRT) | Oral HRT ∞ VTE, stroke; Transdermal HRT ∞ lower VTE risk |

| Skeletal System | Osteoporosis, increased fracture risk | Rarely, epiphyseal plate closure (in youth) | Aromatase Inhibitors ∞ accelerated bone loss |

| Reproductive System | Vaginal atrophy, low libido, irregular cycles | Endometrial hyperplasia, fibroids, breast tenderness | SERMs ∞ tissue-specific effects (e.g. Tamoxifen on uterus) |

| Central Nervous System | Mood disturbances, cognitive decline, sleep disruption | Headaches, mood swings | Variable effects depending on intervention and individual |

| Metabolic System | Insulin resistance, visceral fat gain | Fluid retention, weight gain | Impact on lipid profiles and glucose metabolism varies |

How Do Genetic Variations Influence Individual Responses to Estrogen Regulation Protocols?

What Is the Interplay with the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis?

The HPG axis is the master regulator of sex steroid production, including estrogen. Interventions targeting estrogen regulation inevitably interact with this axis, often through feedback mechanisms. For instance, exogenous estrogen administration (HRT) provides negative feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary, suppressing endogenous GnRH, LH, and FSH production. This can lead to ovarian quiescence in women and testicular suppression in men, impacting fertility.

Conversely, agents like Gonadorelin directly stimulate the pituitary, bypassing hypothalamic inhibition, to maintain LH and FSH pulsatility. SERMs like Clomid act at the hypothalamus and pituitary to block estrogen’s negative feedback, thereby increasing GnRH, LH, and FSH release, which then stimulates gonadal hormone production. This is why Clomid is used to stimulate fertility in men with low testosterone.

Understanding these feedback loops is paramount for clinical translation. For example, in men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), the exogenous testosterone provides negative feedback, suppressing natural testosterone production and potentially impacting fertility. This is why adjunctive therapies like Gonadorelin or Enclomiphene are often included, to preserve testicular function and fertility by maintaining HPG axis signaling.

The precise titration of these interventions requires continuous monitoring of not only estrogen and testosterone levels but also LH, FSH, and other relevant biomarkers to ensure the HPG axis is modulated in a controlled and predictable manner. Unintended suppression or overstimulation of this axis can lead to a range of considerations, from fertility impairment to hormonal imbalances that manifest systemically.

What Regulatory Frameworks Govern the Long-Term Safety Monitoring of Estrogen Interventions?

References

- Mirkin, S. & Pickar, J. H. (2015). Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) ∞ a review of clinical data. Maturitas, 80(1), 52-57.

- Stuenkel, C. A. et al. (2015). Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 100(11), 3923-3972.

- Santen, R. J. et al. (2010). Estrogen and Progestin Use in Postmenopausal Women. Endocrine Reviews, 31(6), 815-843.

- Lobo, R. A. (2017). Hormone replacement therapy ∞ current concepts and controversies. Climacteric, 20(2), 108-114.

- Chlebowski, R. T. et al. (2018). Estrogen plus progestin and estrogen alone in postmenopausal women and health outcomes during 18 years of follow-up in the Women’s Health Initiative. JAMA, 319(15), 1591-1602.

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. (2012). AACE Releases Guidelines for Menopausal Hormone Therapy. AAFP, 86(9), 857-858.

- Greising, S. M. et al. (2009). The effect of hormone replacement therapy on muscle strength in postmenopausal women ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause, 16(6), 1206-1214.

- Tsutsui, K. et al. (2012). Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone (GnIH) and its receptor ∞ discovery, structure, and function. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 33(3), 284-298.

- Plant, T. M. & Marshall, G. R. (2001). The neurobiology of GnRH pulsatility. Endocrine Reviews, 22(3), 309-322.

- Zeleznik, A. J. & Plant, T. M. (2015). The neuroendocrine control of the hypothalamo-pituitary ∞ gonadal axis in primates. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 27(1), 1-10.

Reflection

Understanding the intricate dance of hormones within your own biological system is a powerful step toward reclaiming vitality. The journey of exploring estrogen regulation interventions is not simply about managing symptoms; it is about recognizing the profound connections between your internal chemistry and your lived experience. Each piece of knowledge gained, from the fundamental role of estrogen to the complexities of clinical protocols, contributes to a more complete picture of your unique physiology.

This knowledge serves as a compass, guiding you toward informed decisions about your health. It encourages a proactive stance, where you become an active participant in your wellness narrative. The goal is to move beyond a reactive approach to symptoms, instead cultivating a deep appreciation for the body’s inherent capacity for balance. Consider this exploration a foundational element in your personal pursuit of optimal function, a reminder that true well-being stems from a harmonious internal environment.

Your path to hormonal equilibrium is distinct, shaped by your individual genetics, lifestyle, and health history. Armed with a deeper understanding of the potential considerations and benefits of estrogen regulation, you are better equipped to engage in meaningful dialogue with healthcare professionals. This collaborative approach ensures that any personalized wellness protocol aligns precisely with your needs, supporting your body’s innate intelligence and fostering a sustained state of health.