Fundamentals

The decision to begin a hormonal optimization protocol is deeply personal, often marking the start of a chapter aimed at reclaiming vitality. The choice to pause or end that protocol is equally significant, and the physical and emotional shifts that follow can feel abrupt and confusing.

You may notice a return of the very symptoms that first led you to seek support ∞ the fatigue, the mental fog, the shifts in mood or physical comfort. This experience is valid and rooted in the intricate communication network of your endocrine system. Your body had grown accustomed to a new state of biochemical equilibrium, and its interruption requires a period of recalibration.

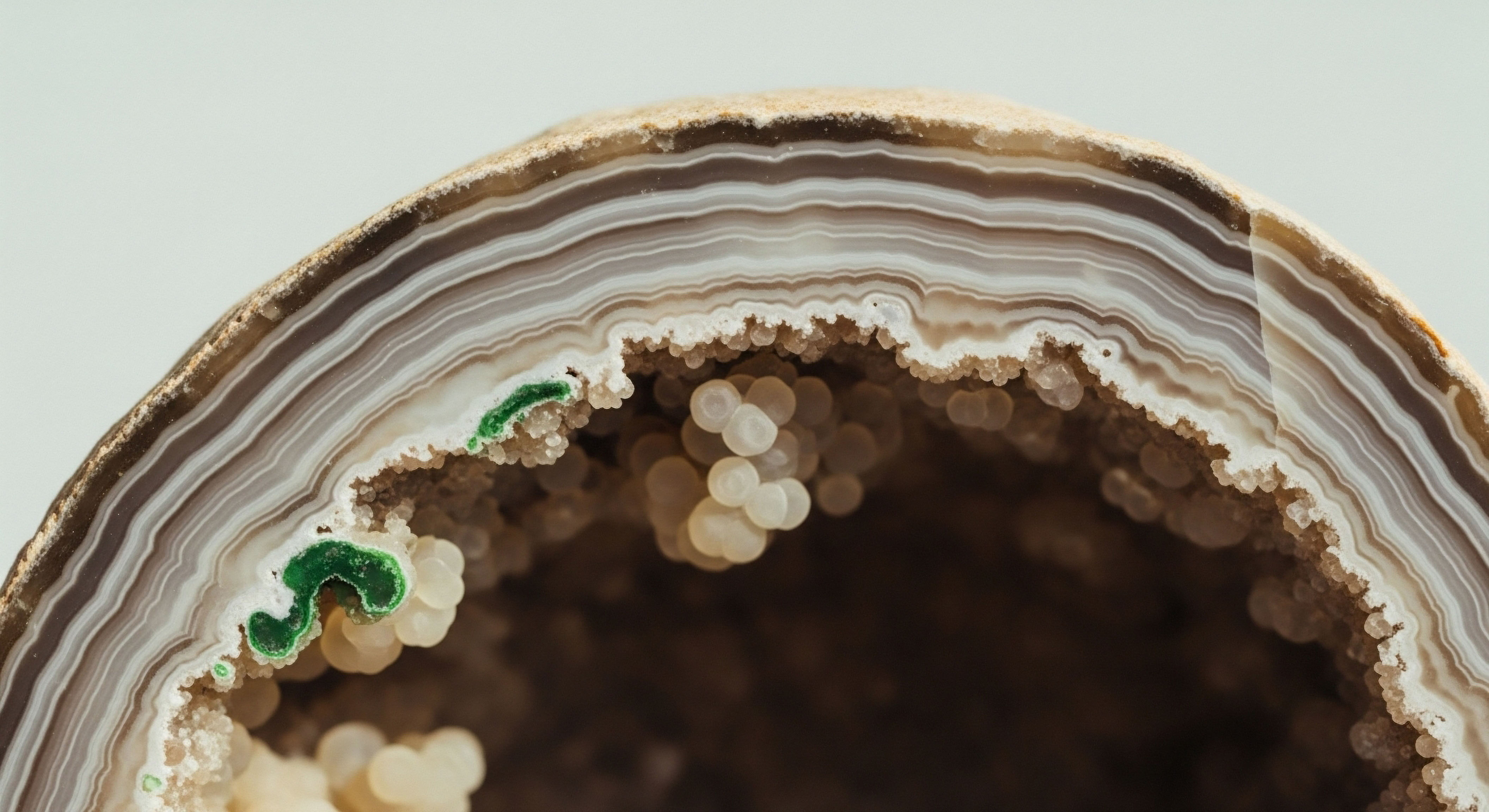

Think of your endocrine system as a vast, interconnected signaling network. Hormones are the chemical messengers that travel through this network, carrying precise instructions to virtually every cell, tissue, and organ. This system governs everything from your metabolic rate and sleep cycles to your mood and cognitive function.

When you undergo a therapy like TRT or female hormone support, you are introducing an external signal to stabilize and optimize this network. The body, in its remarkable efficiency, adapts. It recognizes the presence of these external hormones and, in response, downregulates its own internal production to maintain balance. This is a normal, predictable biological process.

The Principle of Endocrine Adaptation

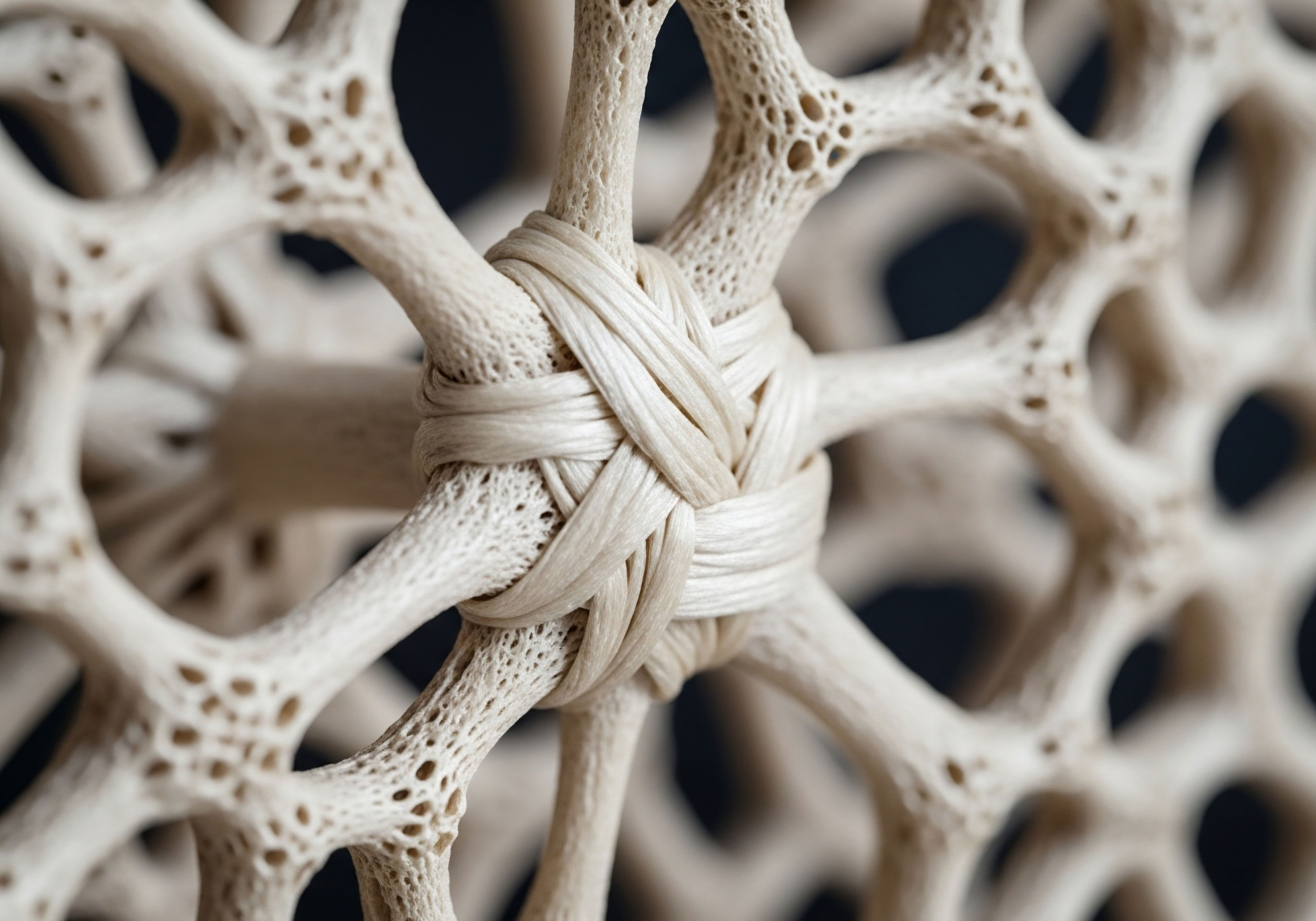

When hormonal support is withdrawn, the network is suddenly faced with a void. The external messengers have ceased their arrival, but the internal production facilities have not yet received the signal to resume their full operational capacity.

This gap between the cessation of therapy and the restoration of the body’s own hormonal rhythm is where the physiological consequences are most acutely felt. The system must first recognize the deficit and then begin the complex process of reawakening its own production lines.

For men, this primarily involves the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The hypothalamus must begin producing Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) again, which in turn signals the pituitary gland to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH is the specific messenger that travels to the Leydig cells in the testes, instructing them to produce testosterone.

After a period of external testosterone administration, this entire axis has been suppressed. Its reawakening is not instantaneous; it is a gradual, biological process that can take weeks or even months.

The abrupt absence of hormonal support creates a biological gap, initiating a complex and gradual process for the body to restart its own internal production.

For women discontinuing menopausal hormone therapy, the experience is different but follows a similar principle of adaptation. The body had adjusted to a consistent supply of estrogen and progesterone, which managed symptoms like hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness, while also providing protective benefits for bone density and cardiovascular health.

When this support is removed, the underlying state of menopause is unmasked. The ovaries have not been “reawakened” because their decline in function is a natural part of aging. Instead, the body is confronted with the low-estrogen state it was being shielded from, leading to a potential resurgence of menopausal symptoms.

What Are the Initial Physical and Emotional Signals?

The initial period following the interruption of hormonal support is characterized by the body’s response to a sudden deficit. The symptoms that manifest are direct consequences of the roles these hormones play in daily physiological function.

- Energy and Mood Regulation ∞ Both testosterone and estrogen are critical modulators of neurotransmitter systems in the brain, influencing mood, motivation, and cognitive clarity. A sharp decline can lead to pervasive fatigue, irritability, anxiety, or a depressive state. This is a physiological response to the brain adjusting to a different chemical environment.

- Metabolic Adjustments ∞ Hormones are central to metabolic regulation. Testosterone contributes to lean muscle mass maintenance and metabolic rate. Estrogen influences fat distribution and insulin sensitivity. Halting therapy can lead to a decrease in muscle mass, an increase in adipose tissue (particularly visceral fat), and changes in how the body processes energy.

- Return of Specific Symptoms ∞ For men, this can mean a decline in libido and erectile function. For women, this often involves the return of vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) and urogenital symptoms (vaginal dryness and urinary discomfort).

Understanding these initial responses as a predictable biological process is the first step. This is your body communicating its attempt to find a new baseline. The journey of interrupting hormonal therapy is one of physiological readjustment, and recognizing the underlying mechanisms can provide a sense of clarity and control during a period of significant change.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the initial symptoms, a more detailed clinical examination reveals the specific systemic adjustments that occur when hormonal optimization protocols are discontinued. The process is far more intricate than a simple return to a pre-treatment state. The body’s endocrine axes, having been modulated by external inputs, must undergo a structured, often challenging, recalibration. The nature of this recalibration depends entirely on the type of therapy being discontinued and the individual’s underlying physiology.

The Male Experience Unpacking HPG Axis Suppression and Restart Protocols

For a man discontinuing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), the central challenge is the suppression of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Exogenous testosterone creates a powerful negative feedback loop. The hypothalamus detects high levels of circulating androgens and ceases its pulsatile release of GnRH. Without GnRH, the pituitary gland stops secreting LH and FSH.

The absence of LH signaling causes the Leydig cells within the testes to become dormant, halting endogenous testosterone production. This state of secondary hypogonadism is an expected outcome of effective TRT.

When TRT is stopped, particularly abruptly, the body is left with neither an external nor an internal source of testosterone. This hormonal vacuum is what precipitates the intense fatigue, mood disturbances, and loss of libido often reported. The goal of a structured discontinuation plan is to bridge this gap by actively stimulating the HPG axis to resume its function. This is where a Post-TRT or Fertility-Stimulating Protocol becomes essential.

These protocols are designed to sequentially reactivate each component of the axis:

- Direct Testicular Stimulation ∞ Medications like Gonadorelin or Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) are often used. hCG mimics the action of LH, directly stimulating the dormant Leydig cells to begin producing testosterone and increasing testicular volume. This step helps to “prime the pump,” ensuring the testes are responsive when the body’s own LH signal returns.

- Pituitary Stimulation via Estrogen Modulation ∞ Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) like Clomiphene Citrate (Clomid) or Tamoxifen Citrate are central to restarting the pituitary. These compounds work by blocking estrogen receptors at the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. The brain perceives lower estrogen activity, which prompts it to increase the production of GnRH and, subsequently, LH and FSH. This elevated LH signal is what drives the newly primed testes to produce testosterone.

- Managing Aromatization ∞ As endogenous testosterone production resumes, some of it will naturally convert to estrogen via the aromatase enzyme. In some cases, an Aromatase Inhibitor (AI) like Anastrozole may be used judiciously to prevent estrogen levels from rising too high, which could re-suppress the HPG axis.

A guided discontinuation protocol for men is a systematic process of re-engaging the body’s suppressed hormonal production machinery, component by component.

The timeline for HPG axis recovery is highly variable and depends on factors like the duration of TRT, the dosage used, and the individual’s age and baseline testicular function. Consistent monitoring of blood markers (Total and Free Testosterone, LH, FSH, Estradiol) is critical to titrate the protocol effectively.

The Female Experience Unmasking Menopause and Its Health Implications

For a woman who stops menopausal hormone therapy, the physiological narrative is different. The therapy was not suppressing a functional system; it was replacing the declining output of the ovaries. Therefore, discontinuation does not involve “restarting” a system. Instead, it unmasks the full biological reality of the postmenopausal state. The consequences can be categorized into two distinct phases.

Immediate Symptom Recurrence

The most immediate effect is often a rapid return of the symptoms that the therapy was managing. The body, which had adapted to stable levels of estrogen and progesterone, is now exposed to their absence. This can trigger:

- Intense Vasomotor Symptoms ∞ The return of hot flashes and night sweats can be more severe than before therapy began, as the body experiences a steep drop in estrogen rather than a gradual decline.

- Urogenital Atrophy ∞ Estrogen is vital for the health of vaginal and urinary tissues. Its withdrawal can lead to a rapid onset of dryness, discomfort during intercourse (dyspareunia), and increased urinary urgency or infections.

- Psychological and Cognitive Shifts ∞ Mood lability, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and a sense of “brain fog” can reappear as the neuroprotective and mood-stabilizing effects of estrogen and progesterone are lost.

Long-Term Health Trajectory Alterations

Beyond the immediate symptoms, discontinuing hormonal support alters the long-term health risk profile. The therapy provides protective benefits that are forfeited upon cessation.

The following table outlines the key physiological systems affected when a woman stops menopausal hormone therapy:

| Physiological System | State During Hormone Therapy | State After Discontinuation | Potential Long-Term Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal System | Estrogen slows bone resorption by osteoclasts, preserving bone mineral density (BMD). | The brake on osteoclast activity is removed, leading to accelerated bone loss. | Increased risk of developing osteoporosis and fragility fractures. |

| Cardiovascular System | Estrogen has favorable effects on lipid profiles (lowering LDL, raising HDL) and vascular function. | Lipid profiles may shift toward a more atherogenic pattern. Vascular benefits cease. | Potential increase in long-term risk for cardiovascular events. |

| Metabolic Function | Hormonal balance supports insulin sensitivity and helps manage central adiposity. | Increased tendency toward insulin resistance and accumulation of visceral fat. | Higher risk for developing metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. |

What Happens When Peptide Therapies Are Stopped?

Peptide therapies, such as those used to stimulate Growth Hormone (GH) release (e.g. Sermorelin, Ipamorelin/CJC-1295), operate on a different principle. These peptides are secretagogues; they signal the pituitary gland to produce and release more of its own GH. They do not directly suppress the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Somatotropic axis in the same way TRT suppresses the HPG axis.

Consequently, when peptide therapy is discontinued, the body does not experience a withdrawal syndrome in the classical sense. The external stimulus is removed, and the pituitary simply returns to its baseline level of GH production. The physiological consequences are a gradual reversal of the benefits obtained during therapy.

This may include a slow return of increased body fat, decreased muscle mass, lower energy levels, and changes in sleep quality. The key distinction is that the body’s natural production system remains intact, albeit at its pre-therapy, often age-diminished, capacity.

Academic

An academic exploration of the consequences of interrupting hormone replacement therapy requires a shift in perspective from systemic outcomes to the underlying cellular and neuroendocrine mechanisms. The cessation of hormonal support initiates a cascade of events that reverberate through intracellular signaling pathways, gene expression, and the delicate crosstalk between the endocrine and central nervous systems.

The focus here is on the biological inertia of these systems and the molecular recalibration that must occur when a potent external signaling molecule is withdrawn.

Neuroendocrine Disruption the Central Governor’s Response

The brain is a primary target for sex hormones. Both testosterone and estradiol readily cross the blood-brain barrier and act as powerful neuromodulators. They influence the synthesis, release, and reuptake of key neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. During hormonal therapy, the brain habituates to a specific neurochemical milieu. The interruption of this therapy constitutes a significant perturbation to this established homeostasis.

For instance, in men discontinuing TRT, the abrupt decline in testosterone and its aromatized metabolite, estradiol, directly impacts dopaminergic pathways associated with motivation, reward, and executive function. This is a potential neurobiological correlate for the commonly reported symptoms of apathy, anhedonia, and “brain fog.” The recovery of the HPG axis is not merely a gonadal event; it is a neuroendocrine process.

The pulsatility of GnRH from the hypothalamus is governed by a complex network of upstream neurons (e.g. Kiss1 neurons), which are themselves sensitive to circulating androgen and estrogen levels. The restoration of normal pulsatile signaling after prolonged suppression is a process of neuronal re-sensitization that can be protracted.

The interruption of hormonal therapy is a profound neuroendocrine event, forcing the brain’s chemical architecture to re-adapt to a new hormonal reality.

In postmenopausal women stopping estrogen therapy, the effects on the serotonergic and cholinergic systems are particularly relevant. Estrogen is known to upregulate tryptophan hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in serotonin synthesis, and has a supportive role in cholinergic neurons critical for memory and cognition.

The withdrawal of estrogen can thus lead to a state of relative neurotransmitter deficit, contributing to mood lability and cognitive complaints. The vasomotor instability (hot flashes) that resurges is itself a centrally mediated phenomenon, originating from a narrowing of the thermoneutral zone within the hypothalamus, a change directly linked to estrogen withdrawal.

Metabolic Whiplash Cellular and Systemic Consequences

The discontinuation of hormonal therapies induces significant shifts in metabolic programming. These changes extend beyond simple alterations in body composition to the core machinery of cellular energy regulation.

This table details the metabolic shifts following the cessation of different hormonal therapies:

| Hormonal Therapy Type | Key Metabolic Regulator | Effect of Discontinuation on Cellular Level | Systemic Clinical Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone (Men) | Androgen Receptor (AR) Signaling | Decreased AR activation in skeletal muscle leads to reduced protein synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis. Increased lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity in visceral adipocytes. | Sarcopenic obesity ∞ loss of lean muscle mass concurrent with an increase in visceral adipose tissue (VAT). Worsening insulin resistance. |

| Estrogen (Women) | Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) Signaling | Downregulation of ERα-mediated pathways in the liver, adipose tissue, and pancreas. This affects hepatic lipid metabolism and pancreatic beta-cell function. | Adverse shift in lipid profiles (increased LDL/HDL ratio, increased triglycerides). Increased risk for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and impaired glucose tolerance. |

| Growth Hormone (Peptides) | IGF-1 Signaling Pathway | Reduced hepatic production of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1). Decreased IGF-1 signaling in peripheral tissues reduces lipolysis and anabolic processes. | Reduced resting metabolic rate. Increase in subcutaneous and visceral fat mass. Diminished insulin sensitivity over time. |

The concept of metabolic whiplash describes the rapid reversal of the favorable metabolic environment that was established during therapy. For example, a patient discontinuing GH peptide therapy will experience a decline in IGF-1 levels.

Since IGF-1 promotes lipolysis and has insulin-sensitizing effects, its reduction can lead to a swift increase in fat mass and a decline in glucose control, as demonstrated in studies on GH withdrawal in adults with GHD. These changes are not merely a return to baseline; the velocity of the change itself can be a metabolic stressor.

How Does Receptor Density Change after Therapy?

A critical question in endocrinology is the effect of exogenous hormone administration on target tissue receptor density. Does prolonged exposure to high-normal levels of a hormone lead to a downregulation of its corresponding receptors, making the body less sensitive upon withdrawal? The evidence is complex and tissue-specific.

In the context of androgen receptors (AR), continuous high-dose exposure can lead to a reduction in AR expression in some tissues as a homeostatic mechanism. Upon withdrawal of TRT, a man may face a dual challenge ∞ critically low levels of the ligand (testosterone) and potentially reduced density or sensitivity of the receptor.

This could theoretically prolong the period of symptomatic hypogonadism even after endogenous testosterone production begins to recover. The efficacy of HPG axis restart protocols, therefore, depends not only on restoring hormone levels but also on the integrity of the target cell’s ability to respond.

The process of discontinuing hormonal support is a profound biological challenge that tests the resilience and adaptability of the body’s core regulatory networks. The physiological consequences are a direct reflection of the interruption of deeply integrated signaling pathways that govern everything from neuronal communication to cellular energy metabolism. A successful navigation of this process requires a clinical approach that appreciates this complexity and supports the body’s attempt to re-establish its own sovereign control.

References

- Rastrelli, G. et al. “Testosterone replacement therapy.” Sexual medicine and andrology. Springer, Cham, 2019. 245-269.

- “The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society.” Menopause, vol. 29, no. 7, 2022, pp. 767-794.

- Cowen, P. J. and G. M. Goodwin. “The clinical pharmacology of the HPA axis.” Neuropsychopharmacology ∞ The Fifth Generation of Progress. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 2002.

- Johannsson, G. et al. “Growth hormone treatment of adults with growth hormone deficiency ∞ benefits and risks.” Hormone Research in Paediatrics, vol. 51, no. Suppl. 1, 1999, pp. 35-41.

- Bhasin, S. et al. “Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715-1744.

- McHenry, J. N. et al. “Sex differences in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders.” Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 16, no. 6, 2014, pp. 1-9.

- Carroll, P. V. et al. “Growth hormone deficiency in adulthood and the effects of growth hormone replacement ∞ a review.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 83, no. 2, 1998, pp. 382-395.

- Rainey, W. E. et al. “The role of the adrenal cortex in the development of the metabolic syndrome.” The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, vol. 127, no. 3-5, 2011, pp. 181-187.

- Anawalt, B. D. “Approach to the patient with gynecomastia.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 5, 2013, pp. 1796-1804.

- Garnock-Jones, K. P. “Sermorelin/tesamorelin ∞ a review of its use in the management of abdominal fat in patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy.” Drugs, vol. 71, no. 9, 2011, pp. 1177-1190.

Reflection

You have now seen the intricate biological map that outlines the body’s response to the cessation of hormonal support. This knowledge provides a framework, a way to translate personal feelings of change into a language of physiological processes. The path you have been on, and the one you are contemplating, is written in the chemical syntax of your own unique biology.

The information presented here is a powerful tool, yet it represents only the universal principles of a deeply individual experience.

Charting Your Own Course

Your personal health narrative is composed of more than just hormonal axes and cellular receptors. It includes your unique genetics, your lifestyle, your nutritional status, and your personal goals. The decision to start, continue, or stop any therapeutic protocol is a point of intersection between clinical science and your lived reality.

Consider how the patterns described here align with your own observations. What aspects of this biological story resonate with your experience? Where do you see your own journey reflected in these mechanisms?

This understanding is the foundation upon which true partnership in health is built. It allows for a different kind of conversation with your clinical guide ∞ one that moves from a simple reporting of symptoms to a collaborative exploration of your body’s internal environment.

The ultimate aim is to achieve a state of function and vitality that is sustainable and authentic to you. This knowledge empowers you to be an active participant in that process, to ask more precise questions, and to co-author the next chapter of your health story with intention and clarity.