Fundamentals

The Internal Architect of Your Emotional World

You feel it as a subtle shift in your internal landscape. A change in your capacity for stress, a flicker in your motivation, or a new weight to your daily moods. These experiences are real, and they are deeply rooted in your body’s intricate biochemistry.

Understanding your emotional state begins with recognizing the profound influence of hormones, particularly testosterone, as a primary architect of your internal world. Its role extends far beyond the physical attributes it shapes; it is a key modulator of the very neurochemical systems that govern how you feel, moment to moment. The journey to understanding your own vitality requires a clear view of how this powerful steroid hormone communicates with your brain.

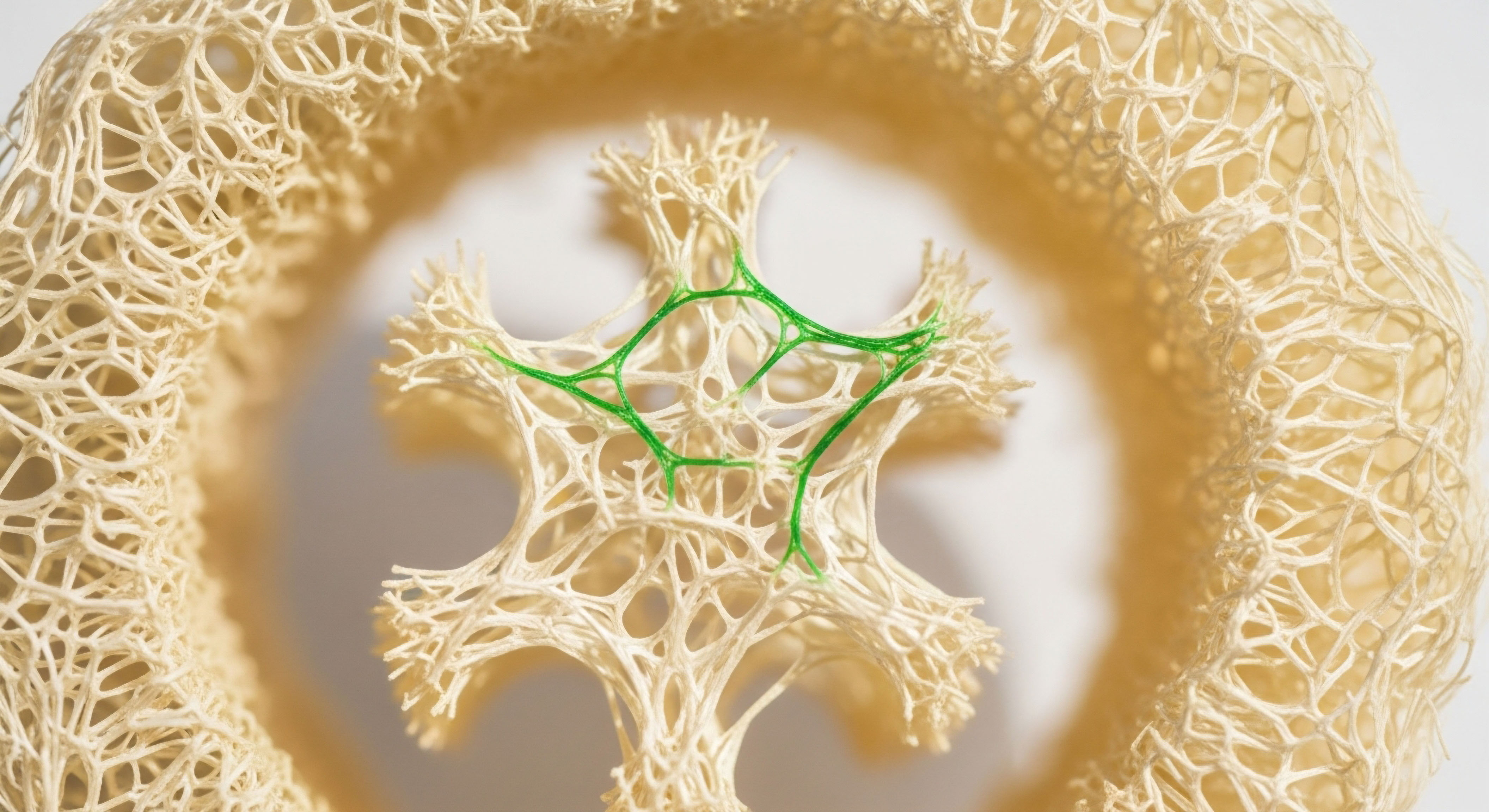

Testosterone does not operate in isolation. It functions within a sophisticated feedback system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, a constant communication loop between your brain and reproductive organs. This axis acts like a central command, regulating testosterone production to maintain a delicate equilibrium.

When this balance is optimal, it supports stable mood, drive, and a sense of well-being. A disruption in this system, often experienced as a gradual decline with age or due to other health factors, can manifest as irritability, low mood, or a diminished sense of resilience. Your subjective experience of your emotional state is a direct reflection of this internal biological dialogue.

The Brain’s Receptors Awaiting the Message

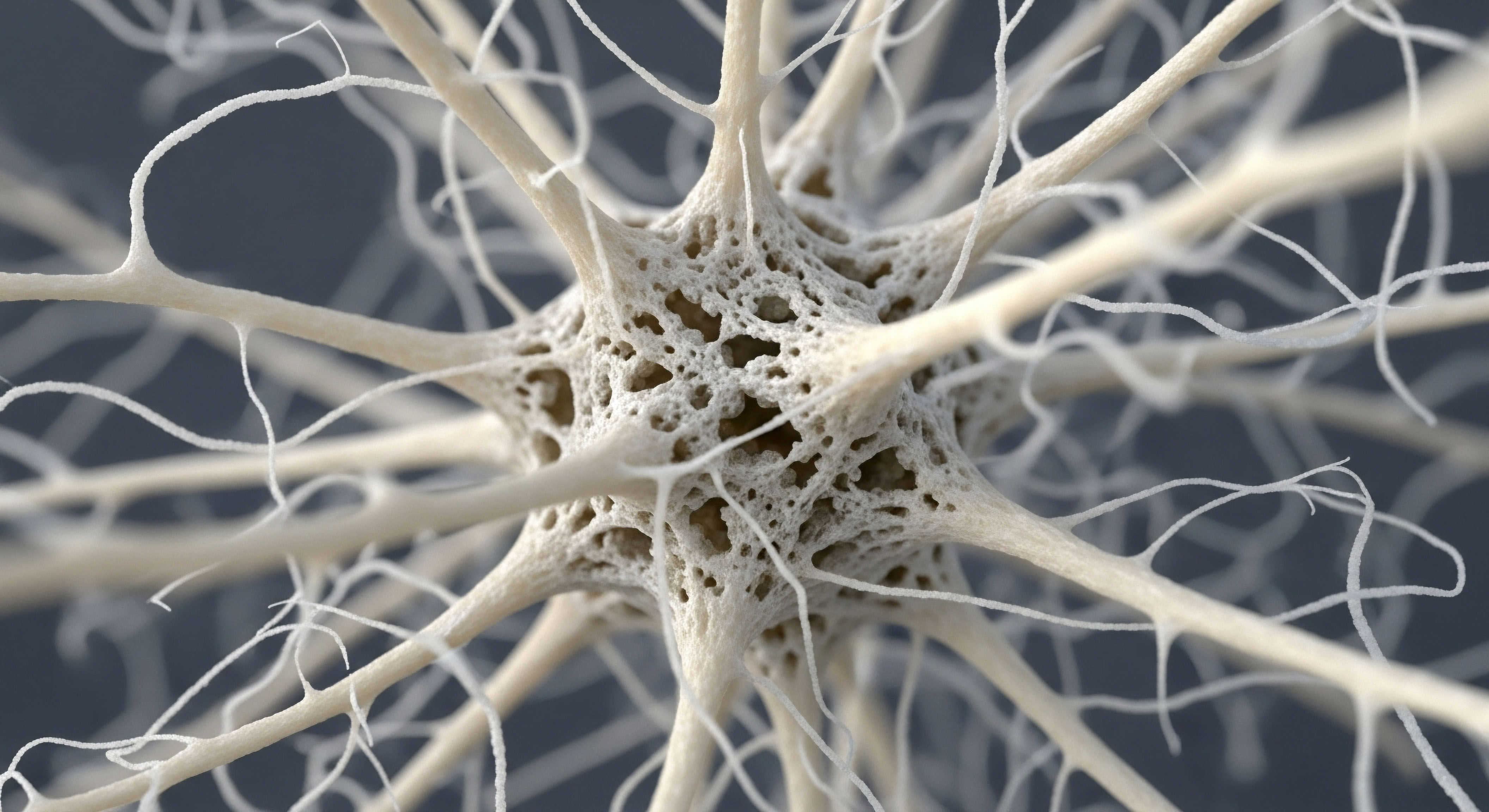

To influence your emotions, testosterone must first interact directly with your brain cells. It accomplishes this by binding to specific docking sites called androgen receptors, which are found in high concentrations in brain regions critical to emotional processing. Think of these receptors as locks, and testosterone as the key.

When testosterone binds to these receptors in areas like the amygdala (your brain’s emotional processing hub) and the prefrontal cortex (the center of executive function and emotional regulation), it initiates a cascade of cellular events that alter brain activity. This direct binding is one of the primary ways testosterone shapes your response to social cues and emotional stimuli.

Furthermore, testosterone’s influence is amplified through its conversion into other potent hormones directly within the brain. Through a process called aromatization, testosterone is transformed into estradiol, a form of estrogen. Both testosterone and its metabolite, estradiol, then act on their respective receptors (androgen and estrogen receptors), often within the same brain regions, to modulate neuronal function.

This dual-action mechanism allows for a more complex and refined level of control over the neurochemical environment that underpins your emotional state. It is this intricate interplay of hormones and their metabolites that creates the foundation for your emotional well-being.

Your subjective feelings are deeply connected to the molecular conversations happening within your brain, orchestrated by hormones like testosterone.

How Does Testosterone Directly Influence Brain Chemistry?

The most direct way testosterone asserts its influence is by modulating the activity of neurotransmitters, the chemical messengers that allow your brain cells to communicate. Two of the most significant neurotransmitter systems affected by testosterone are the dopamine and serotonin systems. Dopamine is intrinsically linked to motivation, reward, and feelings of pleasure.

Testosterone can enhance dopamine release and increase the sensitivity of dopamine receptors, effectively amplifying the brain’s reward circuitry. This mechanism helps explain the connection between healthy testosterone levels and feelings of drive, ambition, and a zest for life. When testosterone levels are suboptimal, this dopaminergic support diminishes, which can contribute to feelings of apathy and low motivation.

The relationship with serotonin is equally significant. Serotonin is a key regulator of mood, anxiety, and emotional stability. Testosterone helps modulate serotonin pathways, and low levels of the hormone have been associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety. By supporting the function of these crucial neurotransmitter systems, testosterone helps to build a resilient and stable emotional foundation.

Hormonal optimization protocols, therefore, are designed to restore this essential biochemical support, allowing for a recalibration of the brain’s natural mood-regulating systems. The goal is to re-establish the internal environment where these neurochemical conversations can proceed without interruption, fostering a state of emotional balance and strength.

Intermediate

Recalibrating the System Hormonal Optimization Protocols

When the body’s natural production of testosterone declines, leading to symptoms that impact quality of life, a clinical intervention may be necessary to restore balance. This process, often referred to as hormonal optimization, is a targeted medical strategy designed to re-establish physiological hormone levels.

For men experiencing andropause, or what is clinically termed hypogonadism, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is a primary protocol. The objective is to alleviate symptoms like low mood, irritability, and diminished motivation by replenishing the body’s supply of this critical hormone. This recalibration directly addresses the neurochemical deficits that arise from insufficient testosterone, providing the brain with the necessary tools to regulate emotional states effectively.

A standard protocol for men often involves weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate, a bioidentical form of the hormone. This method ensures stable, predictable levels of testosterone in the bloodstream, avoiding the emotional fluctuations that can accompany less consistent delivery methods. To maintain the body’s own hormonal ecosystem, this is often paired with other supportive medications.

Gonadorelin, for instance, is a peptide that stimulates the pituitary gland to maintain natural testosterone production and support testicular function. Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, may be used to manage the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, preventing potential side effects and ensuring the hormonal ratio remains balanced. This multi-faceted approach is designed to restore the entire hormonal axis, not just supplement a single hormone.

Effective hormonal therapy is a process of systemic recalibration, aiming to restore the body’s complex and interconnected signaling pathways.

Tailoring Protocols for Men and Women

The application of hormonal optimization is distinct for men and women, reflecting the unique physiological needs of each. While men typically require higher doses to restore youthful levels, women benefit from much smaller, carefully calibrated doses of testosterone to address symptoms like low libido, mood changes, and fatigue, particularly during the perimenopausal and postmenopausal transitions.

For women, low-dose Testosterone Cypionate may be administered via subcutaneous injection, offering a precise and manageable approach to restoring hormonal balance. This is often complemented by progesterone, which plays a crucial role in mood regulation and sleep quality, especially as natural production wanes.

The table below outlines a comparison of typical starting protocols for men and women, illustrating the tailored nature of these therapies.

| Protocol Component | Standard Male Protocol (Andropause) | Female Protocol (Perimenopause/Postmenopause) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Hormone | Testosterone Cypionate (200mg/ml) | Testosterone Cypionate (low dose) |

| Typical Dosage | 100-200mg weekly (intramuscular) | 10-20 units weekly (subcutaneous) |

| Supportive Medications | Gonadorelin, Anastrozole, Enclomiphene | Progesterone, possibly low-dose Anastrozole |

| Primary Goal | Restore physiological levels, improve mood, energy, and libido | Alleviate symptoms of hormonal fluctuation, improve libido and mood |

The Role of Peptides in Supporting Neuro-Endocrine Function

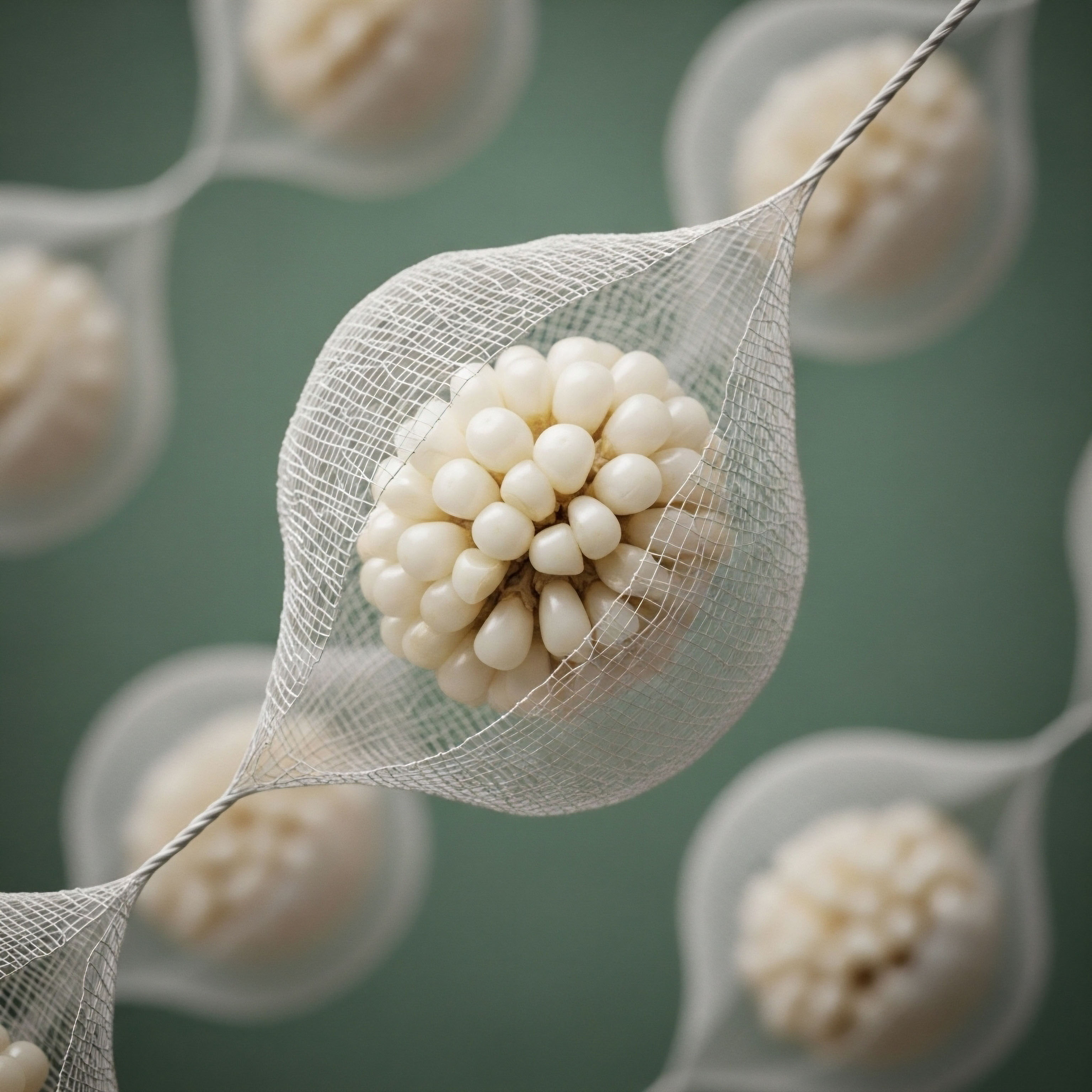

Beyond direct hormonal replacement, peptide therapies represent another frontier in personalized wellness. Peptides are short chains of amino acids that act as signaling molecules in the body, and certain peptides can be used to support the HPG axis and overall endocrine function.

For individuals seeking to enhance the body’s own hormone production or as part of a post-TRT protocol, peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295 are utilized. These are Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone (GHRH) analogues that stimulate the pituitary gland to produce more of the body’s own growth hormone. This can have indirect benefits on mood and well-being by improving sleep quality, enhancing recovery, and promoting a healthier metabolic state, all of which are intertwined with emotional health.

These protocols are built on a deep understanding of the body’s signaling systems. By providing the precise molecular messengers the body needs, these therapies can help restore function in a targeted and sophisticated manner. The ultimate aim is to move beyond a simple model of hormone replacement and toward a more holistic vision of endocrine system support, where the body’s innate capacity for balance and vitality is fully restored.

Academic

Modulation of the Amygdala-Prefrontal Circuitry

The influence of testosterone on emotional states is mediated through its complex modulation of specific neural circuits, most notably the connectivity between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The amygdala, a core component of the limbic system, is densely populated with androgen receptors and is integral to the processing of fear, aggression, and social-emotional cues.

The PFC, particularly the ventrolateral and orbitofrontal regions, exerts top-down regulatory control over the amygdala, inhibiting impulsive emotional responses and facilitating considered social behavior. Research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has demonstrated that testosterone levels directly impact the functional connectivity between these two regions.

Studies have shown that higher levels of endogenous testosterone are associated with reduced functional connectivity between the amygdala and the PFC during social-emotional tasks. This suggests that testosterone can attenuate the prefrontal cortex’s regulatory grip on the amygdala, potentially leading to more automatic, less inhibited emotional responses.

This mechanism may underlie the observed associations between high testosterone levels and behaviors such as dominance and aggression. Conversely, in men with lower testosterone, there is often greater recruitment of the PFC to regulate amygdala activity, indicating a more effortful cognitive control of emotional impulses. This neurobiological framework provides a mechanistic explanation for how hormonal fluctuations can translate into observable changes in mood and social behavior.

Genomic and Non-Genomic Actions on Neurotransmission

Testosterone’s effects on the brain can be categorized into two primary pathways ∞ genomic and non-genomic. The genomic pathway involves testosterone diffusing across the cell membrane, binding to intracellular androgen receptors, and then translocating to the nucleus to act as a transcription factor.

This process alters the expression of specific genes, leading to the synthesis of new proteins, including enzymes and neurotransmitter receptors. This is a relatively slow process, taking hours to days to manifest. For example, testosterone can upregulate the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, thereby increasing the overall capacity of the dopaminergic system.

The non-genomic pathway, in contrast, involves rapid, membrane-level actions that do not require gene transcription. Testosterone can bind to membrane-associated receptors, activating second messenger systems like G-protein coupled receptors and influencing ion channel activity. This allows for the rapid modulation of neuronal excitability and neurotransmitter release.

One such mechanism involves the facilitation of nitric oxide (NO) synthase, an enzyme that produces nitric oxide, a critical signaling molecule in the brain. This rapid, non-genomic action can synergize with the effects of estradiol (aromatized from testosterone) to enhance dopamine release in response to salient cues, a mechanism crucial for motivation and reward processing.

Testosterone sculpts emotional responses by directly altering the functional architecture of the brain’s emotional regulation circuits.

What Is the Impact on Neurotransmitter Systems?

Testosterone exerts a profound influence on several key neurotransmitter systems that are fundamental to mood regulation. Its interaction with the dopaminergic system is particularly well-documented. By enhancing dopamine synthesis and release in critical reward pathways, such as the mesolimbic pathway connecting the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens, testosterone can increase motivation and drive.

Animal studies have shown that circulating testosterone levels directly correlate with dopamine activity in these regions. This provides a neurochemical basis for the feelings of confidence and assertiveness associated with optimal testosterone levels.

The serotonergic system is also a primary target of testosterone’s modulatory effects. Testosterone has been shown to influence serotonin function by affecting the sensitivity of serotonin receptors and the activity of the serotonin transporter (SERT), the protein responsible for serotonin reuptake.

Low testosterone levels have been linked to alterations in this system that mirror those seen in depressive disorders. Clinical studies have indicated that testosterone replacement therapy can be as effective as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in improving mood in men with hypogonadism, highlighting the hormone’s critical role in maintaining serotonergic tone.

The following table summarizes the primary neurochemical actions of testosterone on key mood-regulating systems.

| Neurotransmitter System | Primary Action of Testosterone | Resulting Effect on Emotional State |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Increases synthesis, release, and receptor sensitivity in reward pathways. | Enhanced motivation, drive, and sense of reward. |

| Serotonin | Modulates receptor sensitivity and transporter function. | Improved mood stability, reduced anxiety and irritability. |

| GABA | Metabolites of testosterone can act as positive allosteric modulators of GABA-A receptors. | Anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) and calming effects. |

Finally, metabolites of testosterone, such as androstenediol, can act as positive allosteric modulators of GABA-A receptors, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter system in the brain. By enhancing GABAergic transmission, these metabolites can produce anxiolytic effects, contributing to a sense of calm and well-being.

This multifaceted influence across multiple neurotransmitter systems demonstrates that testosterone’s role in emotional regulation is a complex and integrated process. It is a systems-level modulator that fine-tunes the very neurochemical symphony that creates our emotional experience.

Can Androgen Receptor Sensitivity Affect Mood Regulation?

The variability in individual responses to testosterone is partly explained by genetic differences in the androgen receptor (AR). The AR gene contains a polymorphic region with a variable number of CAG repeats. The length of this CAG repeat sequence is inversely related to the transcriptional activity of the receptor; a shorter repeat length generally corresponds to a more sensitive and efficient receptor.

This means that two individuals with identical testosterone levels can have markedly different physiological and psychological responses based on their AR sensitivity.

This genetic variable has significant implications for emotional regulation. Individuals with more sensitive androgen receptors may experience more pronounced effects from a given level of testosterone. Research has begun to explore how AR genotype interacts with hormone levels to influence the development and function of brain structures like the amygdala.

For instance, AR sensitivity has been shown to affect the volume of amygdala subregions differently in males and females during adolescence, a critical period for both brain development and hormonal changes.

Understanding an individual’s AR genotype could, in the future, allow for even more personalized hormonal optimization protocols, tailored not just to circulating hormone levels, but to the body’s unique ability to respond to those hormonal signals. This represents a key area of ongoing research in the field of personalized and preventative medicine.

- Amygdala ∞ This almond-shaped structure in the brain’s temporal lobe is a critical processing center for emotions, particularly fear and pleasure. Testosterone directly influences its activity through a high concentration of androgen receptors.

- Prefrontal Cortex ∞ The frontmost part of the frontal lobe, this brain region is responsible for complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision making, and moderating social behavior. It exerts top-down control over the amygdala.

- Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis ∞ This refers to the interconnected system of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and gonads. This axis is the primary regulator of testosterone production and release in the body.

References

- Bialek, M. et al. “Neuroprotective role of testosterone in the nervous system.” Polish Journal of Pharmacology, vol. 56, no. 5, 2004, pp. 509-18.

- Zitzmann, Michael. “The role of the CAG repeat androgen receptor polymorphism in therapy.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 97, no. 7, 2012, pp. 2285-94.

- Balthazart, Jacques, and Gregory F. Ball. “Testosterone-induced aromatase activity in the preoptic area of the male quail.” Journal of Neuroendocrinology, vol. 18, no. 5, 2006, pp. 339-41.

- van Wingen, G. A. et al. “Endogenous testosterone modulates prefrontal ∞ amygdala connectivity during social emotional behavior.” Cerebral Cortex, vol. 20, no. 4, 2010, pp. 883-91.

- McHenry, J. et al. “The role of testosterone in social behavior and mood.” Behavioral Neuroscience, vol. 128, no. 2, 2014, pp. 154-67.

- Celec, P. et al. “On the effects of testosterone on brain behavioral functions.” Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 9, 2015, p. 12.

- Arnow, B. A. et al. “Women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder compared to normal females ∞ a functional magnetic resonance imaging study.” Neuroscience, vol. 158, no. 2, 2009, pp. 484-502.

- Simerly, R. B. et al. “Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain ∞ an in situ hybridization study.” Journal of Comparative Neurology, vol. 294, no. 1, 1990, pp. 76-95.

- Campbell, E. et al. “Associations between testosterone, estradiol, and androgen receptor genotype with amygdala subregions in adolescents.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 136, 2022, p. 105615.

- Peper, J. S. et al. “Testosterone and the adolescent brain ∞ an overview of structural and functional MRI studies.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 35, no. 8, 2011, pp. 1687-98.

Reflection

Your Biology Is Your Story

The information presented here provides a map, a detailed guide to the intricate biological landscape that shapes your emotional life. It connects the subjective feelings of motivation, stability, and well-being to the objective, measurable actions of hormones and neurotransmitters within your brain. This knowledge is the first, most critical step.

It transforms the abstract sense of feeling “off” into a clear understanding of a physiological process that can be addressed. Your personal health narrative is written in this very biology. Recognizing the characters ∞ the hormones, the receptors, the neural pathways ∞ allows you to become an active participant in that story.

The path forward involves translating this foundational knowledge into a personalized strategy, a clinical partnership aimed at recalibrating your unique system to support a life of vitality and optimal function. Your journey is your own, but the principles of your biology are universal.

Glossary

your emotional state

androgen receptors

emotional regulation

neurotransmitter systems

testosterone levels

serotonin pathways

hormonal optimization protocols

hormonal optimization

testosterone replacement therapy

hypogonadism

testosterone cypionate

anastrozole

gonadorelin

functional magnetic resonance imaging

studies have shown that

testosterone replacement