Fundamentals

You feel it, this subtle shift in your body’s rhythm. It might be a sense of fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch, or a new awareness of your heartbeat during moments of quiet. Your body is communicating, sending signals that its internal equilibrium is changing.

This experience is the starting point for a deeper understanding of your own biology. The journey to exceptional heart health begins with acknowledging these signals and learning to interpret their meaning. We will explore the foundational lifestyle elements that govern cardiovascular wellness, viewing your body as an integrated system where every choice creates a biological consequence.

The conversation about heart health often starts with diet and exercise, and for good reason. These are the powerful, daily inputs that directly influence the cardiovascular system. A diet rich in nutrient-dense foods provides the raw materials for cellular repair and function.

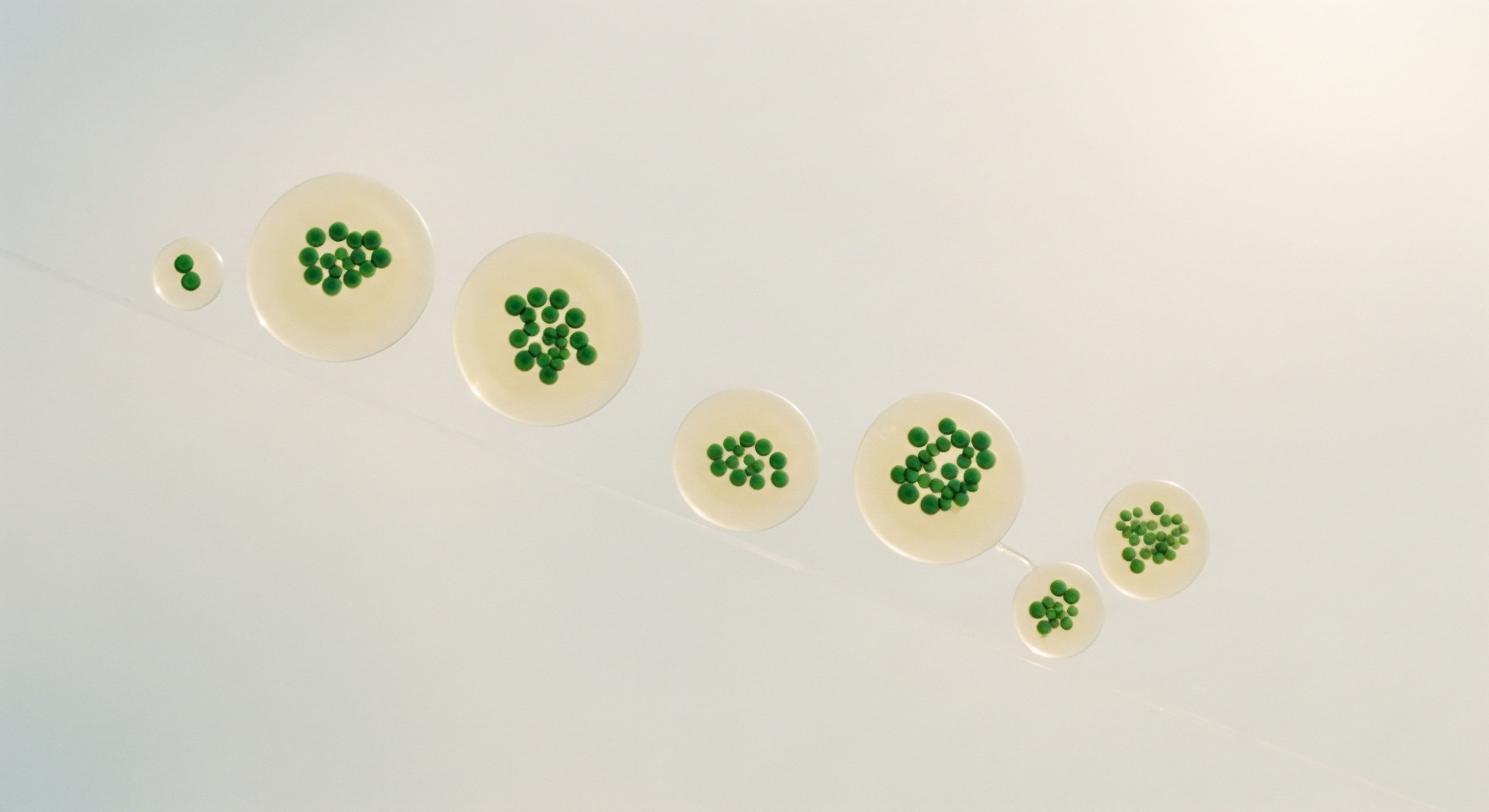

Think of foods high in fiber, such as whole grains, fruits, and vegetables, as regulators of your internal ecosystem. They help manage cholesterol levels and maintain stable blood sugar, preventing the metabolic dysregulation that precedes cardiovascular strain. Including sources of unsaturated fats like avocados, nuts, and fatty fish provides essential lipids that support arterial flexibility and reduce inflammation. These dietary patterns are a direct investment in the structural integrity of your heart and blood vessels.

A nutrient-rich diet provides the fundamental building blocks for a resilient cardiovascular system.

Physical activity is the other cornerstone of this foundation. Regular movement trains your heart to be more efficient. With consistent aerobic exercise, such as brisk walking, cycling, or swimming, the heart muscle strengthens, allowing it to pump more blood with less effort.

This increased efficiency lowers your resting heart rate and blood pressure, two critical markers of cardiovascular health. Activity also enhances your body’s sensitivity to insulin, a key hormone that regulates blood sugar. By improving insulin function, you protect your arteries from the damaging effects of high glucose levels. The goal is to integrate movement into the fabric of your life, making it a consistent practice that supports your body’s dynamic needs.

The Unseen Architects of Health

Beyond the well-known pillars of diet and exercise lie two factors that profoundly shape your cardiovascular destiny ∞ sleep and stress management. Sleep is a period of intense biological restoration. During deep sleep, your body repairs tissues, consolidates memories, and, critically, regulates the hormones that control stress and appetite.

Inadequate or fragmented sleep disrupts this delicate process, leading to elevated levels of cortisol, the primary stress hormone. Chronic elevation of cortisol can increase blood pressure, promote weight gain, and drive inflammation, creating a cascade of effects that directly compromise heart health. Prioritizing seven to nine hours of quality sleep each night is a non-negotiable aspect of cardiovascular maintenance.

Stress itself is a biological reality, a response to perceived threats. The issue arises when this response becomes chronic. The constant activation of the “fight-or-flight” system keeps heart rate and blood pressure persistently high, placing mechanical stress on the entire circulatory system.

Learning to manage stress through techniques like mindfulness, deep breathing, or biofeedback is not an indulgence; it is a clinical necessity. These practices help to regulate the nervous system, shifting it from a state of high alert to one of rest and repair. By actively managing your response to stress, you are directly intervening in the physiological processes that can lead to heart disease.

Intermediate

Understanding the fundamental lifestyle factors for heart health provides a solid base. The next layer of comprehension involves examining how these factors interact with the body’s intricate hormonal and metabolic signaling pathways. Your cardiovascular system operates within a complex web of biochemical communication.

The choices you make daily directly influence this network, either promoting stability or creating the conditions for dysfunction. This section explores the physiological mechanisms that connect your lifestyle to your heart, moving from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’.

The regulation of blood pressure offers a clear example of this interplay. Blood pressure is controlled by a sophisticated system involving the kidneys, brain, and adrenal glands. When you consume a diet high in sodium and low in potassium, you alter the fluid balance in your bloodstream, which can increase blood volume and pressure.

Physical activity helps to improve the flexibility of your blood vessels, allowing them to expand and contract more easily to accommodate blood flow. This vascular compliance is a key feature of a healthy cardiovascular system. Chronic stress, however, introduces a complicating factor. It triggers the release of catecholamines like adrenaline and cortisol, which constrict blood vessels and increase heart rate, forcing the system to operate under sustained high pressure. Over time, this can lead to arterial stiffness and hypertension.

What Is the Role of Metabolic Health?

Metabolic health is the engine room of cardiovascular wellness. At its center is the hormone insulin, which is responsible for shuttling glucose from the blood into cells for energy. A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars forces the pancreas to produce large amounts of insulin.

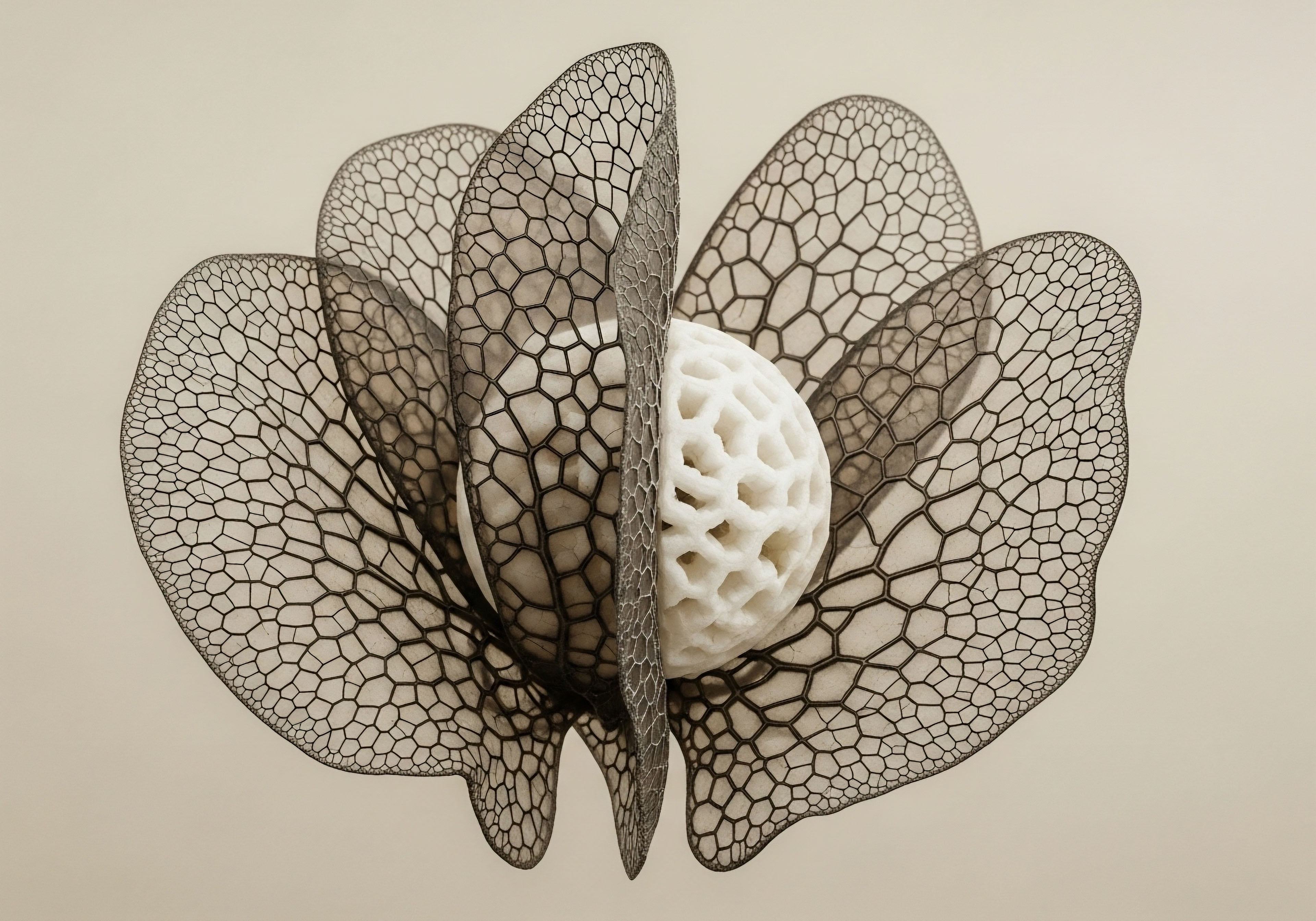

Over time, cells can become less responsive to insulin’s signals, a condition known as insulin resistance. This forces the pancreas to work even harder, creating a state of high circulating insulin (hyperinsulinemia) and high blood sugar (hyperglycemia). This metabolic state is profoundly damaging to the cardiovascular system. High glucose levels can directly damage the delicate lining of the arteries, known as the endothelium, initiating the process of atherosclerosis, or plaque buildup.

Insulin resistance is a key metabolic disturbance that directly contributes to arterial damage and cardiovascular disease.

Physical activity is a powerful tool for maintaining insulin sensitivity. During exercise, your muscles can take up glucose from the blood with less need for insulin, easing the burden on the pancreas. A diet focused on whole foods, fiber, and healthy fats also helps to stabilize blood sugar and insulin levels. These lifestyle interventions are not just about weight management; they are about maintaining the metabolic flexibility that protects your heart at a cellular level.

Key Lifestyle Interventions and Their Mechanisms

To provide a clearer picture, the following table outlines specific lifestyle choices and their direct physiological impact on cardiovascular and metabolic health.

| Lifestyle Factor | Primary Mechanism of Action | Cardiovascular Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Exercise | Increases nitric oxide production, improves mitochondrial efficiency, and enhances insulin sensitivity. | Lowers resting blood pressure, improves blood vessel flexibility, and reduces metabolic risk. |

| High-Fiber Diet | Binds to cholesterol in the digestive tract and slows glucose absorption. | Lowers LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and stabilizes blood sugar levels. |

| Adequate Sleep | Regulates cortisol and ghrelin/leptin levels, and promotes cellular repair. | Reduces systemic inflammation, lowers stress hormone levels, and helps regulate blood pressure. |

| Stress Management | Downregulates the sympathetic nervous system and reduces cortisol output. | Lowers chronic heart rate and blood pressure, and reduces inflammation. |

This table illustrates that each lifestyle factor has a specific, measurable biological effect. These are not abstract concepts but direct interventions in your body’s operating system. By understanding these mechanisms, you can approach your health with a sense of purpose and precision, knowing that each healthy choice is a deposit into the bank of your long-term wellness.

- Smoking Cessation ∞ Quitting smoking is the single most effective lifestyle change for reducing heart disease risk. Tobacco smoke contains compounds that directly damage the arterial walls and promote the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

- Alcohol Moderation ∞ Excessive alcohol consumption can contribute to high blood pressure, an irregular heartbeat, and damage to the heart muscle itself. Limiting intake is a direct measure to protect cardiac function.

- Weight Management ∞ Maintaining a healthy weight reduces the overall workload on the heart and decreases the risk of developing related conditions like hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and sleep apnea, all of which are major drivers of cardiovascular disease.

Academic

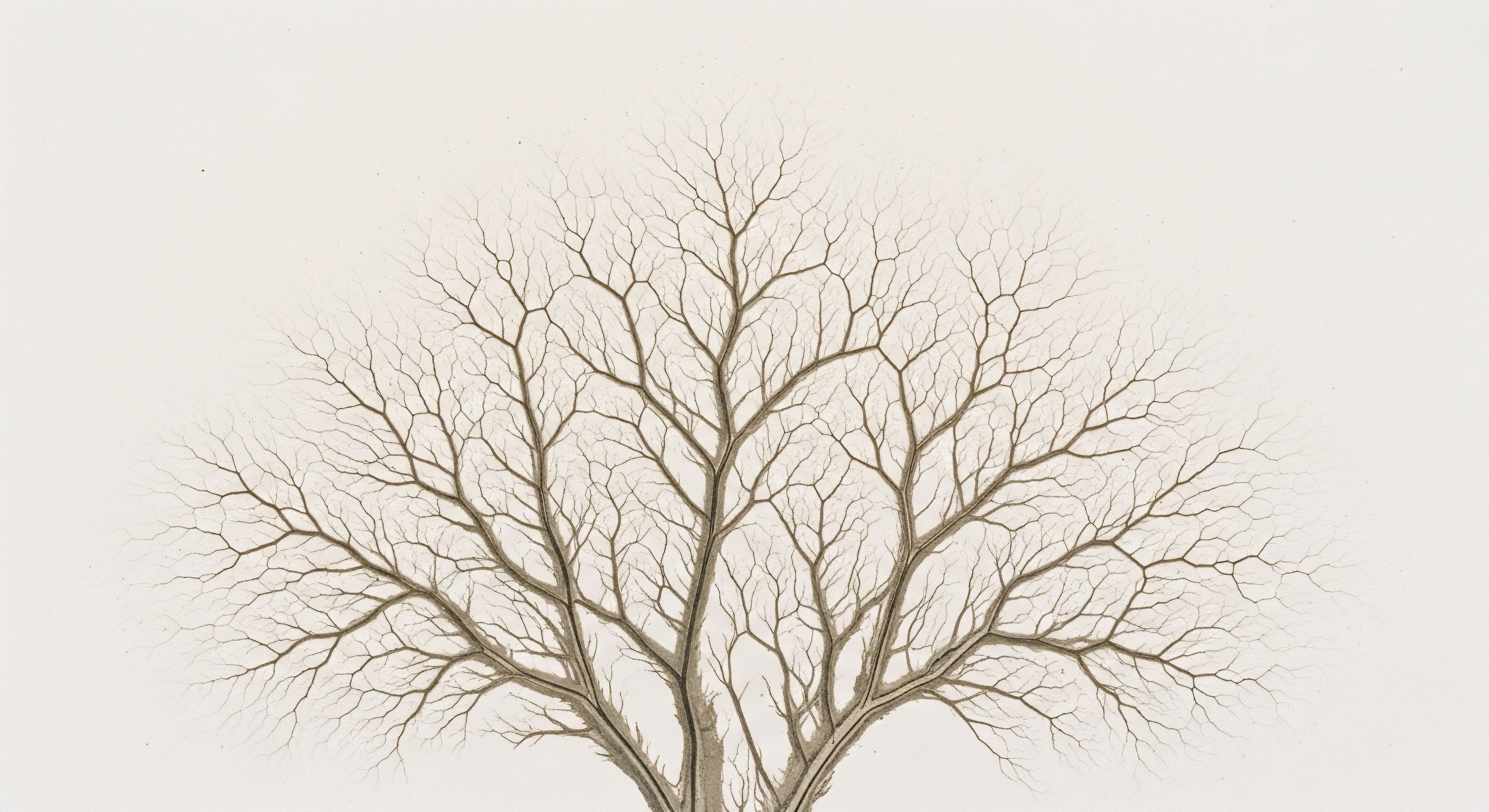

A sophisticated analysis of cardiovascular health requires moving beyond isolated lifestyle factors to a systems-biology perspective. This view considers the deeply interconnected nature of the endocrine, nervous, and immune systems, and how their interactions govern the health of the heart and vasculature.

The central thesis is that cardiovascular disease is often the clinical manifestation of systemic dysregulation, particularly within the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the metabolic pathways controlled by insulin and related hormones. Lifestyle inputs are the primary modulators of these systems.

Chronic psychological and physiological stress serves as a potent activator of the HPA axis, leading to sustained, non-diurnal secretion of cortisol. From a biochemical standpoint, hypercortisolemia induces a state of catabolism and insulin resistance. Cortisol directly antagonizes insulin’s action at the cellular level, promoting gluconeogenesis in the liver and decreasing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues.

This creates a hyperglycemic environment that, as previously discussed, is a primary driver of endothelial dysfunction through the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). AGEs cross-link with collagen in the arterial walls, leading to a loss of vascular elasticity and the initiation of atherosclerotic lesions.

Chronic HPA axis activation is a primary upstream driver of the metabolic and inflammatory cascades that result in cardiovascular pathology.

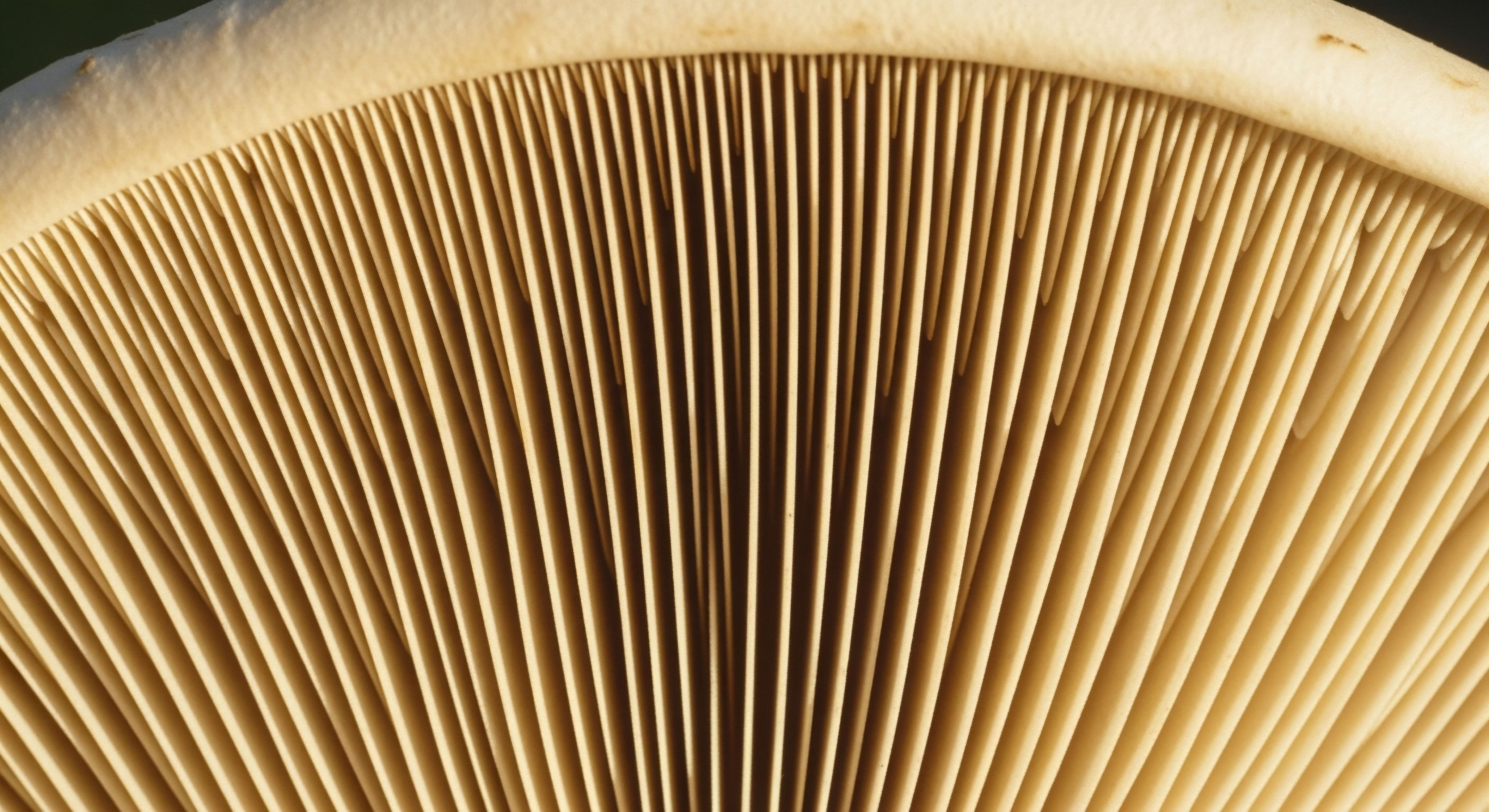

Furthermore, the inflammatory response is inextricably linked to this process. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), are upregulated in states of chronic stress and metabolic syndrome. These cytokines not only contribute to insulin resistance but also directly promote the development of atherosclerosis.

They stimulate the expression of adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface, which facilitates the recruitment of monocytes. Once inside the arterial wall, these monocytes differentiate into macrophages, ingest oxidized LDL cholesterol, and become foam cells ∞ the hallmark of the fatty streak, the earliest stage of an atherosclerotic plaque. Lifestyle interventions, therefore, can be viewed as powerful anti-inflammatory modulators.

How Do Hormones Regulate Cardiovascular Function?

The endocrine system’s role extends beyond the stress response. Sex hormones, for instance, have significant effects on cardiovascular health. Estradiol in women and testosterone in men have vasoprotective properties. They promote vasodilation through nitric oxide pathways and have favorable effects on lipid profiles.

The decline of these hormones during menopause and andropause, respectively, is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. This highlights the importance of considering hormonal status as part of a comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment, particularly in aging populations.

The following table details the systemic impact of key lifestyle factors on integrated biological pathways.

| Lifestyle Intervention | Affected Biological Axis/Pathway | Systemic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) pathway activation. | Stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis, improves cellular energy sensing, and enhances glucose uptake independent of insulin. |

| Mediterranean Diet Pattern | Modulation of the gut microbiome and production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). | Reduces systemic inflammation, improves endothelial function, and positively influences lipid metabolism. |

| Consistent Sleep Schedule | Normalization of the HPA axis and circadian rhythm alignment. | Reduces morning cortisol spikes, improves insulin sensitivity, and lowers sympathetic nervous system tone. |

| Mindfulness Meditation | Increased parasympathetic nervous system tone via the vagus nerve. | Lowers heart rate variability, reduces circulating catecholamines, and decreases inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP). |

This integrated perspective reveals that lifestyle factors are not simply “good habits.” They are potent tools for modulating the fundamental biological systems that determine health and disease. A diet rich in polyphenols and omega-3 fatty acids, for example, does more than lower cholesterol; it actively shifts the gut microbiome toward a less inflammatory profile and provides the precursors for anti-inflammatory signaling molecules.

Regular physical activity does more than burn calories; it stimulates the release of myokines from muscle tissue, which have systemic anti-inflammatory effects. These are profound biological interventions, accessible through daily choices.

The evidence from large cohort studies is compelling. Individuals who adhere to a combination of these lifestyle practices ∞ maintaining a healthy weight, consuming a nutrient-dense diet, engaging in regular physical activity, not smoking, and managing stress ∞ demonstrate a dramatically lower incidence of cardiovascular events.

This underscores the power of an integrated lifestyle approach to disease prevention. The future of cardiovascular medicine lies in understanding and applying these principles with precision, tailoring them to an individual’s unique physiology and genetic predispositions.

- Nutrient Timing ∞ The timing of meals can influence circadian biology and metabolic health. Time-restricted eating, for instance, has been shown in some studies to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce markers of oxidative stress.

- Social Connection ∞ Strong social ties and a sense of community are associated with lower levels of perceived stress and a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. This highlights the role of psychosocial factors in HPA axis regulation.

- Environmental Exposures ∞ Exposure to air pollution and other environmental toxins can contribute to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, increasing cardiovascular risk. This is an often-overlooked component of a holistic approach to heart health.

References

- O’Connor, D. B. Thayer, J. F. & Vedhara, K. (2021). Stress and Health ∞ A Review of Psychosocial, Biological, and Pharmacological Determinants. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 663 ∞ 688.

- Arnett, D. K. Blumenthal, R. S. Albert, M. A. Buroker, A. B. Goldberger, Z. D. Hahn, E. J. & Ziaeian, B. (2019). 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease ∞ A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 140(11), e596-e646.

- Nystoriak, M. A. & Bhatnagar, A. (2018). Cardiovascular Effects and Benefits of Exercise. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 5, 135.

- Rautiainen, S. Wang, L. Lee, I. M. Manson, J. E. Buring, J. E. & Sesso, H. D. (2016). Dairy consumption in association with weight change and risk of becoming overweight or obese in middle-aged and older women ∞ a prospective cohort study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(4), 979-988.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015 ∞ 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015.

- Chomistek, A. K. Chiuve, S. E. Jensen, M. K. Cook, N. R. Rimm, E. B. & Manson, J. E. (2015). Vigorous physical activity, mediating biomarkers, and risk of myocardial infarction. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 47(5), 989.

- Lavie, C. J. O’Keefe, J. H. Sallis, R. E. (2019). Lifestyle Strategies for Risk Factor Reduction, Prevention, and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 73(14), 1769-1771.

- St-Onge, M. P. Grandner, M. A. McKinnon, R. & Toth, K. (2016). Sleep duration and quality ∞ impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health. Current Cardiology Reports, 18(11), 1-8.

- Varbo, A. Benn, M. Tybjærg-Hansen, A. Jørgensen, A. B. Frikke-Schmidt, R. & Nordestgaard, B. G. (2013). Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 61(4), 427-436.

- Khera, A. V. Emdin, C. A. Drake, I. Natarajan, P. Bick, A. G. Cook, N. R. & Kathiresan, S. (2016). Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(24), 2349-2358.

Reflection

Your Path Forward

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory governing your cardiovascular health. It details the mechanisms and pathways that connect your daily actions to your long-term vitality. This knowledge is the foundation upon which you can build a personalized strategy for wellness.

Your own body, with its unique history and responses, is the ultimate arbiter of what works. The next step is one of introspection and action. Consider where your lifestyle currently aligns with these principles and where there are opportunities for focused change. This journey is about reclaiming a sense of agency over your own health, armed with a deeper understanding of the elegant and complex system you inhabit.

Glossary

heart health

cardiovascular system

blood sugar

physical activity

cardiovascular health

blood pressure

stress management

cortisol

nervous system

lifestyle factors

metabolic health

insulin resistance

atherosclerosis

insulin sensitivity

cardiovascular disease

hpa axis

endothelial dysfunction

nutrient-dense diet