Fundamentals

Your journey toward understanding corporate wellness programs begins with a simple, yet profound, recognition of your own internal landscape. The fatigue that settles deep in your bones, the mental fog that clouds your afternoons, the subtle yet persistent feeling that your vitality is slipping away ∞ these are not mere personal failings.

They are biological signals. When we examine the architecture of workplace wellness initiatives, we are truly asking a deeper question ∞ which approach aligns with the intricate, delicate signaling network of the human body, and which risks disrupting it? The distinction between participatory and health-contingent wellness programs rests on the philosophy of engagement and its direct impact on your personal biology.

A participatory program is an invitation. It is structured around the principle of engagement, offering resources and support without demanding a specific biological outcome. Think of it as access to a library of health. You might be provided with a subsidized gym membership, access to stress-management seminars, or educational resources on nutrition.

The reward, if any, is tied directly to your act of showing up ∞ for yourself. This model acknowledges that the first step, the simple act of participation, is a victory. Its design inherently supports your autonomy, allowing you to engage with health-promoting activities on your own terms, aligning with your body’s readiness for change. The underlying principle is one of support, aiming to lower the barriers to entry for self-care.

The Biological Validation of Showing Up

From a physiological standpoint, the participatory model respects the body’s complex feedback loops. When you engage in an activity like a lunchtime yoga class or a nutrition seminar offered through such a program, the primary biological effect is often a down-regulation of the stress response.

The simple act of carving out time for a health-promoting activity can send a powerful signal to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress command center. This can lead to a reduction in circulating cortisol, the primary stress hormone. Lowering cortisol, even temporarily, has cascading benefits.

It can improve insulin sensitivity, support stable energy levels, and create a more favorable internal environment for metabolic health. This approach works with your biology by fostering consistency over intensity, creating a foundation of stability from which lasting change can be built.

How Does This Feel in Your Body?

The experience of a participatory program is one of reduced pressure. You are encouraged to explore, to learn, and to engage at your own pace. This psychological safety is paramount. It prevents the activation of a threat response that can accompany performance-based expectations.

Instead of your body interpreting the wellness initiative as another metric to meet, another potential failure point, it perceives it as a resource. This feeling of support can enhance parasympathetic nervous system activity ∞ the “rest and digest” state. In this state, your body is better equipped to repair tissues, absorb nutrients, and regulate hormonal cycles. The focus is on building a positive, self-directed relationship with your health, which is the bedrock of sustainable well-being.

Health-contingent programs, conversely, are built upon a structure of specific outcomes. These programs link rewards, such as lower insurance premiums or financial bonuses, to the achievement of predetermined health metrics. This category is further divided into two distinct types.

The first is an “activity-only” program, where you might need to complete a certain number of workouts or walk a set number of steps. The second, and more biologically significant, is the “outcome-based” program. Here, the incentive is tied directly to a measurable biomarker, such as attaining a specific BMI, lowering your cholesterol to a certain level, or demonstrating non-smoker status through testing. This model operates on the principle of direct incentivization for results.

Participatory programs encourage engagement with health resources, while health-contingent programs incentivize the achievement of specific health targets.

This approach introduces a set of external targets that your internal systems are expected to meet. For some individuals, this clear goal-setting can provide powerful motivation. The defined finish line can focus effort and create a clear path to a tangible reward.

However, its success is deeply dependent on an individual’s unique biological context, their starting point, and their body’s capacity to respond to change within a specified timeframe. It frames health as a target to be hit, a perspective that has profound implications for the body’s stress and metabolic systems.

Intermediate

To truly appreciate the functional differences between participatory and health-contingent wellness models, one must look beyond their surface-level structure and examine their interaction with the regulatory and biological systems that govern both our health and our employment.

The legal framework, primarily established by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), provides a critical lens. These regulations were designed to allow for wellness incentives while protecting employees from discriminatory practices. Their rules reveal the deep-seated philosophical divergence between the two program types.

Participatory programs operate under a simple guideline ∞ they must be made available to all similarly situated employees, regardless of health status. Because they do not require an individual to meet a health-related standard to earn a reward, they are subject to very few restrictions.

The value of the reward is not limited by the ACA. This light regulatory touch reflects the program’s core identity as a universally accessible resource. It is a tool, not a test. The focus is on providing opportunity, with the implicit understanding that the journey and its outcomes will be unique for each person.

The Regulatory Maze of Health-Contingent Programs

Health-contingent programs face a much higher level of scrutiny, a direct consequence of their potential to create tiered access to rewards based on health status. The ACA and HIPAA have established five stringent requirements to ensure these programs are reasonably designed and not a subterfuge for penalizing individuals with pre-existing conditions.

- Frequency of Opportunity ∞ Individuals must be given the chance to qualify for the reward at least once per year. This acknowledges that health is a dynamic state, not a static achievement.

- Size of Reward ∞ The total reward is capped. Typically, it cannot exceed 30% of the total cost of employee-only health coverage. This limit can be extended to 50% for programs designed to prevent or reduce tobacco use. This cap prevents the financial stakes from becoming so high that they are coercive.

- Reasonable Design ∞ The program must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” It cannot be a series of arbitrary hurdles. It must have a legitimate wellness goal and a reasonable chance of improving health for those who participate.

- Full Reward Availability ∞ All similarly situated individuals must have the opportunity to earn the full reward. This is where the framework’s most critical safeguard lies. The program must provide a “reasonable alternative standard” (or a complete waiver of the initial standard) for any individual for whom it is unreasonably difficult due to a medical condition, or medically inadvisable, to satisfy the original standard. For example, if a program rewards a certain BMI level, an individual with a medical condition that makes weight loss difficult must be offered another way to earn the reward, such as attending educational sessions.

- Disclosure of Alternatives ∞ The availability of this reasonable alternative standard must be clearly disclosed in all program materials. People must know their rights and options.

What Is the True Message behind These Rules?

These regulations tacitly acknowledge a critical biological reality. A one-size-fits-all health target is scientifically and ethically problematic. By mandating “reasonable alternative standards,” the law concedes that a person’s ability to hit a specific metric like blood pressure or body weight is not solely a matter of willpower.

It is profoundly influenced by genetics, existing medical conditions, and the complex interplay of the endocrine system. This legal architecture is a direct reflection of the body’s complexity, attempting to impose fairness on a system that could otherwise penalize biological predisposition.

The stringent regulations governing health-contingent programs underscore the biological fact that uniform health metrics do not account for individual physiological diversity.

This regulatory difference sets the stage for a deeper analysis of how these programs interact with our hormonal systems. The very structure of a health-contingent program, with its defined targets and financial stakes, can be interpreted by the body as a significant external pressure.

This pressure is mediated by the HPA axis, the same system that governs our response to threats, deadlines, and emotional distress. When faced with the challenge of meeting a specific biometric target to avoid a financial penalty or earn a reward, the brain may initiate a classic stress response. The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then travels to the adrenal glands and stimulates the production of cortisol.

| Feature | Participatory Programs | Health-Contingent Programs |

|---|---|---|

| Incentive Basis | Reward for engagement (e.g. attending a class, signing up for a challenge). | Reward for meeting a specific health outcome (e.g. lowering BMI, achieving a target cholesterol level). |

| Psychological Impact | Fosters autonomy and intrinsic motivation; low pressure. | Can create performance anxiety and reliance on extrinsic motivation; high pressure. |

| Primary Hormonal Influence | Potential to lower cortisol through stress-reducing activities and self-care. | Risk of elevating cortisol due to performance pressure and fear of failure. |

| Regulatory Burden (ACA/HIPAA) | Minimal; must be offered to all similarly situated employees. | High; subject to 5 specific criteria, including reward limits and reasonable alternative standards. |

| Metabolic Implication | Supports metabolic health by reducing the chronic stress load. | May paradoxically hinder metabolic goals (e.g. fat loss) if chronic cortisol elevation promotes insulin resistance. |

A short-term cortisol spike can be beneficial, enhancing focus and mobilizing energy. A chronic elevation, which can result from the sustained pressure of a months-long wellness challenge, has deleterious effects on the very systems these programs aim to improve.

Chronically high cortisol can increase appetite for high-calorie foods, promote the storage of visceral fat (the metabolically dangerous fat around the organs), and interfere with thyroid hormone conversion, potentially slowing metabolism. It can also induce insulin resistance, a state where the body’s cells no longer respond efficiently to insulin, which is the precursor to type 2 diabetes.

The irony is stark ∞ a program designed to improve metabolic health could, through its very design, trigger a hormonal cascade that actively undermines it.

Academic

A rigorous examination of wellness program efficacy requires a shift from broad strokes to high-resolution analysis, moving from intention to clinical outcomes and psychological mechanisms. The scientific literature presents a complex and often sobering picture, challenging the foundational assumptions of many corporate wellness initiatives.

A landmark randomized clinical trial published in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) provides a crucial data point. Researchers studied employees at a large US company over 18 months and found that a comprehensive wellness program produced no significant differences in clinical measures of health, including cholesterol, blood pressure, and BMI, nor did it affect healthcare spending or employment outcomes when compared to a control group.

The program did, however, lead to an increase in self-reported healthy behaviors, such as engaging in regular exercise and actively managing weight.

This divergence between self-reported behavior and objective clinical data is where a deeper physiological inquiry begins. It suggests that the changes prompted by the program may be superficial or insufficient to move the needle on deep-seated biological markers. From a clinical perspective, this is unsurprising.

Conditions like dyslipidemia or hypertension are the result of years of complex interactions between genetics, environment, and behavior. Expecting a generalized, non-clinical intervention to reverse them in a short timeframe may be fundamentally misaligned with the chronicity of metabolic disease. The “Clinical Translator” lens suggests that the program may have successfully changed an employee’s idea of their health without altering the underlying reality of their biochemistry.

The Tyranny of Extrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination Theory

The core mechanism at play in health-contingent programs is extrinsic motivation ∞ the use of external rewards or punishments to drive behavior. While economists and employers have long favored this model, a wealth of psychological research illuminates its limitations, particularly through the framework of Self-Determination Theory (SDT).

SDT posits that for a behavior to become lasting and integrated, it must satisfy three innate psychological needs ∞ autonomy (a sense of volition and control), competence (a feeling of mastery and effectiveness), and relatedness (a sense of belonging and connection).

Health-contingent programs, especially outcome-based ones, can directly threaten the need for autonomy. When a reward is perceived as “controlling,” it can undermine an individual’s sense of personal agency. The reason for exercising or eating differently becomes the pursuit of the reward, not an internal desire for health.

This can trigger a phenomenon known as “motivational crowding-out,” where the external incentive extinguishes pre-existing intrinsic motivation. An employee who once enjoyed walking for stress relief may now view it as a chore to be logged for points, stripping the activity of its inherent value. Once the incentive is removed, the behavior often ceases, as the original internal driver has been supplanted and then lost.

How Does Motivational Pressure Translate to Cellular Stress?

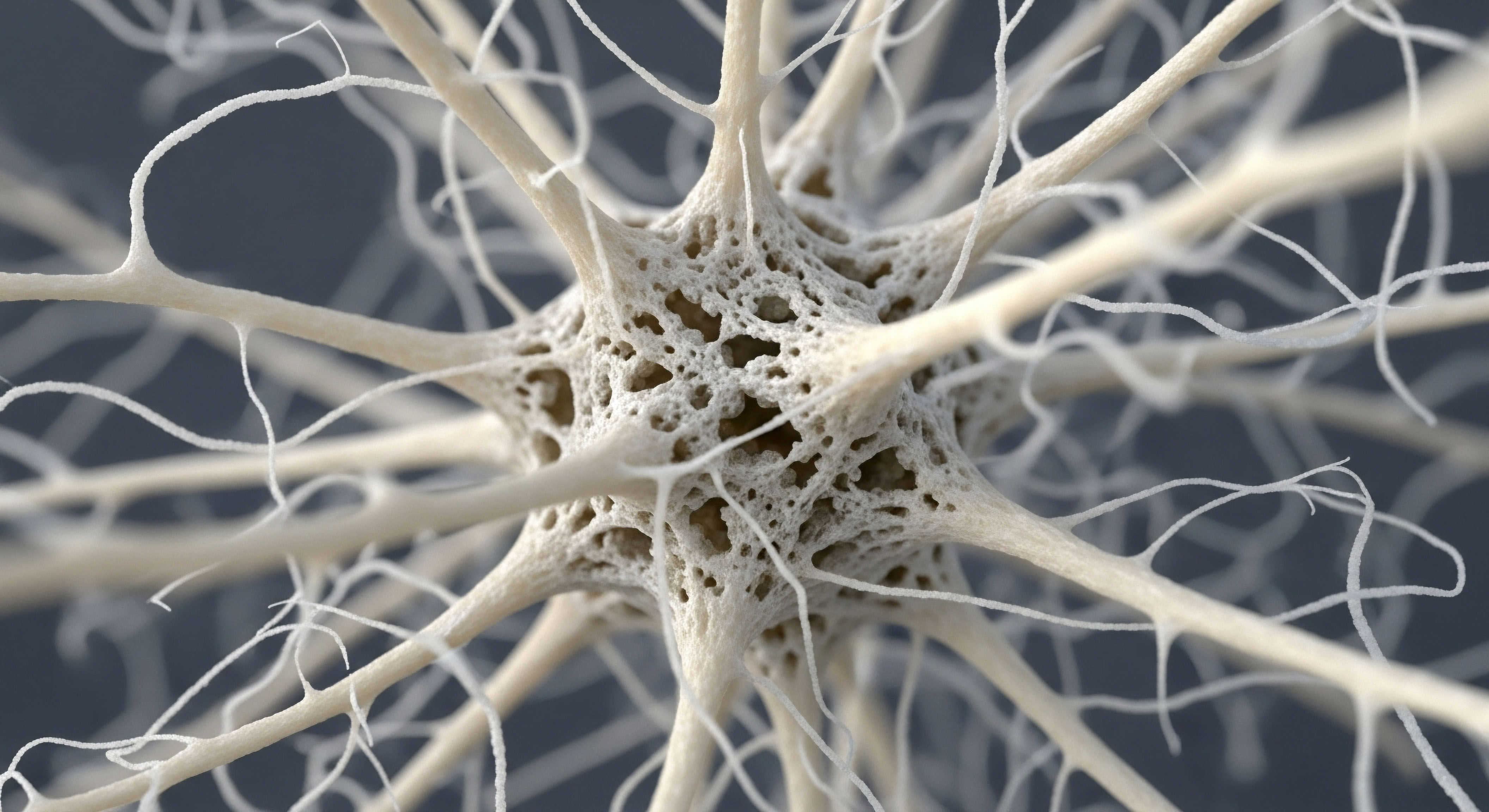

The pressure to meet a specific, often difficult, health target is a potent psychological stressor. This is not merely a subjective feeling; it is a biochemical event. The persistent fear of “failing” the test ∞ of not seeing the number on the scale or the blood pressure cuff drop sufficiently ∞ can create a state of chronic HPA axis activation. This sustained output of cortisol has profound, well-documented consequences that directly oppose the goals of any wellness program.

- Metabolic Disruption ∞ Chronic cortisol elevation promotes gluconeogenesis (the creation of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources) and decreases peripheral glucose uptake, both of which contribute to hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. It also directly impacts adipocyte (fat cell) behavior, favoring the deposition of visceral adipose tissue.

- Endocrine Crosstalk ∞ The HPA axis is deeply interconnected with other hormonal systems. Elevated cortisol can suppress the production of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), leading to disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. In women, this can manifest as menstrual irregularities. In men, it can contribute to the suppression of testosterone production. Furthermore, cortisol can inhibit the conversion of inactive thyroid hormone (T4) to its active form (T3), effectively slowing the body’s metabolic rate.

- Neurochemical Imbalance ∞ The constant stress signaling can alter neurotransmitter balance, depleting serotonin and dopamine, which can lead to low mood and motivation, further hindering an individual’s ability to engage in healthy behaviors.

This creates a vicious physiological cycle. The program designed to improve metabolic health induces a stress response that worsens metabolic parameters. An individual struggling to lose weight may find their efforts futile, in part because their own stress hormones are creating a biological environment conducive to fat storage and insulin resistance.

This is a critical failure of the one-size-fits-all model, as it ignores the individual’s unique endocrine reality. Someone with subclinical hypothyroidism or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is at a significant disadvantage, and the program’s pressure can exacerbate their condition.

A program’s design can trigger a chronic stress response, creating a hormonal environment that actively works against its stated metabolic goals.

This is where truly personalized medicine offers a different paradigm. Protocols like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for men with clinically diagnosed hypogonadism, or the use of specific peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin to support the body’s natural growth hormone pulses, address the root biochemical imbalance.

They do not simply demand a different outcome; they work to change the underlying physiological system to make that outcome possible. A response to the JAMA study noted that a staggering 60% of U.S. adults have at least one chronic condition. A wellness program that fails to account for this reality is poorly designed.

A participatory model, by lowering the stakes and focusing on support and education, is less likely to induce this harmful stress cascade. It allows an individual to engage with resources that can help them, without punishing them for a biology they did not choose.

| Hormonal System | Potential Impact of Participatory Programs | Potential Impact of Health-Contingent Programs |

|---|---|---|

| HPA Axis (Cortisol) | Can lower chronic cortisol by providing stress-reducing activities (e.g. yoga, mindfulness) and fostering a sense of autonomy. | Can elevate chronic cortisol due to performance pressure, fear of financial penalty, and the stress of failing to meet metrics. |

| Metabolic Hormones (Insulin, Leptin) | Supports insulin sensitivity and healthy leptin signaling by reducing the systemic stress load. | Risks inducing insulin resistance and leptin resistance through chronic cortisol elevation. |

| HPG Axis (Testosterone, Estrogen) | Promotes balanced sex hormone production by mitigating HPA axis over-activity. | Can suppress testosterone and disrupt menstrual cycles via cortisol-mediated inhibition of GnRH. |

| Thyroid Hormones (T3, T4) | Supports efficient conversion of T4 to active T3 by reducing stress-related enzymatic inhibition. | May impair T4 to T3 conversion, leading to a functional slowdown in metabolic rate. |

References

- Song, Z. and Baicker, K. “Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes ∞ A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA, vol. 321, no. 15, 2019, pp. 1491-1501.

- Gneezy, U. Meier, S. and Rey-Biel, P. “When and Why Incentives (Don’t) Work to Modify Behavior.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 25, no. 4, 2011, pp. 191-210.

- Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. Self-Determination Theory ∞ Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. The Guilford Press, 2017.

- Kullgren, J. T. et al. “Financial Incentives for Weight Loss in Workplace Wellness Programs.” JAMA Internal Medicine, vol. 174, no. 10, 2014, pp. 1656-1657.

- Chamberlain, R. “A Response to JAMA’s Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes ∞ A Randomized Clinical Trial.” Applied Health Analytics, LLC, 2019.

- Adams, J. et al. “Changing health behaviors using financial incentives ∞ a review from behavioral economics.” BMC Public Health, vol. 11, no. 1, 2011, p. 69.

- Lemmens, K. et al. “A systematic review of the effects of multidisciplinary workplace health promotion programs on absenteeism.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, vol. 50, no. 3, 2008, pp. 310-319.

- Promberger, M. and Marteau, T. M. “When do financial incentives reduce intrinsic motivation? A meta-analysis.” Health Psychology, vol. 32, no. 9, 2013, pp. 950-960.

Reflection

You have now seen the architecture of these programs, not as abstract corporate policies, but as systems that interact directly with your own intricate biology. The knowledge of how an external pressure can become an internal hormonal signal is a powerful tool. It reframes the conversation from one of compliance to one of coherence. Which approach allows your body to find its own state of balance? Which honors the signals it is already sending you?

What Is Your Body’s Preferred Language of Motivation?

Consider your own experiences. When have you felt most aligned with your health goals? Was it when pursuing a specific, externally validated target, or was it when you felt supported to explore and discover what truly nourished you? The answer reveals something profound about your own nervous system and its relationship with motivation.

Understanding this personal feedback loop is the first principle of a truly personalized wellness protocol. The data from large-scale studies is invaluable, but the most important data point is your own lived, biological experience. This knowledge empowers you to seek out environments and strategies that work in concert with your physiology, creating a foundation for vitality that is both resilient and authentic.

Glossary

wellness programs

health-contingent wellness programs

workplace wellness

stress response

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (hpa) axis

cortisol

metabolic health

health-contingent programs

health-contingent wellness

participatory programs

reasonable alternative

endocrine system

hpa axis

insulin resistance

wellness program

randomized clinical trial

self-determination theory

extrinsic motivation

motivational crowding-out

chronic cortisol elevation promotes

testosterone replacement therapy