Fundamentals

Living with an autoimmune condition is an intimate, and often isolating, dialogue with your own body. You become acutely aware of subtle shifts in energy, the onset of pain, or the fog that can cloud your thoughts. These experiences are valid, tangible data points in your personal health story.

When you layer hormonal fluctuations onto this complex internal environment, that dialogue can become confusing and dissonant. It is a lived reality for many, feeling the pull of a monthly cycle or the profound shift of menopause and sensing a direct, yet unexplainable, change in the intensity of your symptoms.

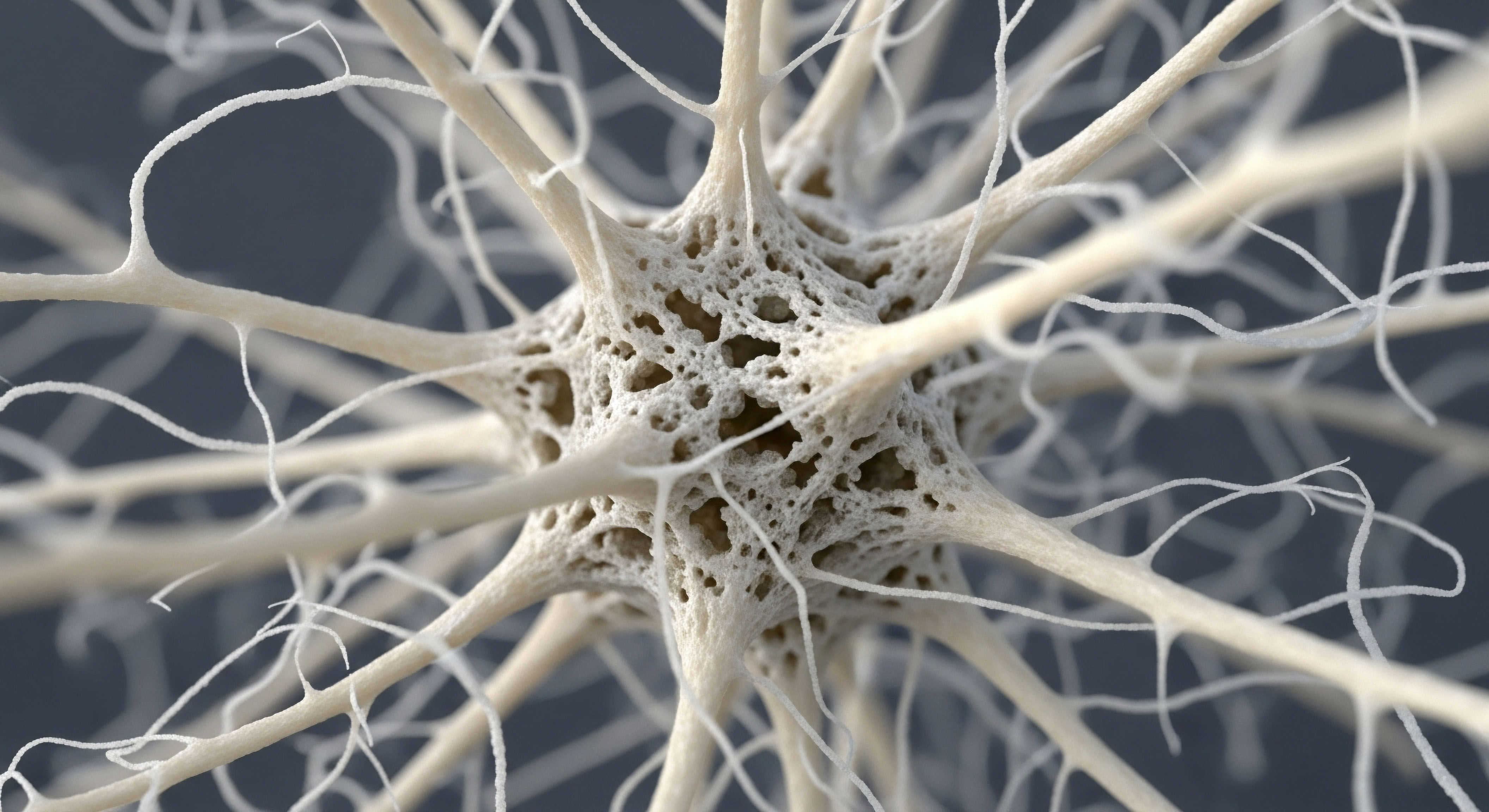

This connection is real. Your endocrine system, the intricate network that produces and manages your hormones, is in constant communication with your immune system. Understanding this conversation is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of control and biological harmony.

Hormones are the body’s primary signaling molecules. Think of them as chemical messengers, dispatched from glands and traveling through the bloodstream to deliver specific instructions to your cells, tissues, and organs. They regulate everything from your metabolism and mood to your sleep cycles and, critically, your immune responses.

Your immune system, in turn, is a vast, intelligent surveillance network designed to protect you. In an autoimmune condition, this network’s communication becomes distorted. It misidentifies the body’s own healthy tissues as foreign threats, launching a sustained, inflammatory attack. The question that follows is a logical and deeply personal one ∞ if hormones are powerful messengers, could recalibrating their signals help quiet this internal conflict?

Hormones function as powerful signaling molecules that directly influence the behavior of the immune system.

The Key Messengers and Their Roles

To grasp the long-term considerations of hormonal optimization, we first need to appreciate the distinct roles of the principal sex hormones. These molecules possess unique properties that can either amplify or soothe the inflammatory signals at the heart of autoimmunity.

Estrogen the Amplifier

Estrogen, primarily known as a female sex hormone, has a complex and powerful influence on the immune system. It is generally immunoenhancing, meaning it can stimulate and heighten immune activity. During a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen levels are higher, which corresponds to the period when autoimmune conditions like Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) are most likely to appear or become more active.

This is because estrogen can encourage the production of antibodies and promote the activity of immune cells that drive inflammatory responses. This biological predisposition helps explain why women are disproportionately affected by autoimmune diseases. For a body already prone to an overactive immune response, high levels of estrogen can sometimes act like fuel on a fire.

Testosterone the Modulator

Testosterone, the primary male sex hormone also present in smaller amounts in women, generally functions as an immunomodulator, often with suppressive effects. It can help temper the immune response, reducing the production of certain inflammatory signaling molecules called cytokines and encouraging the development of regulatory immune cells that keep the system in check.

The lower incidence of autoimmune disease in men is partly attributed to the calming influence of testosterone on the immune system. For individuals with autoimmunity, a deficiency in testosterone could mean losing a key signal for restraint, allowing inflammatory processes to proceed unchecked. Restoring testosterone to an optimal physiological range is therefore a strategy aimed at re-introducing this crucial moderating voice into the immune conversation.

Progesterone the Peacemaker

Progesterone, another key female hormone, has a distinct and often calming effect on the immune system. Its levels rise significantly during pregnancy, a time when the maternal immune system must become tolerant of the fetus. Progesterone helps to inhibit some of the more aggressive, inflammatory parts of the immune response.

It can help shift the immune system away from a state of attack and toward a state of tolerance. Its role in the context of autoimmune conditions is an area of active investigation, with the understanding that its balancing properties could be a valuable component of a comprehensive hormonal strategy.

Understanding these fundamental roles is essential. Hormonal optimization is a process of carefully adjusting the levels of these messengers. The goal is to create a biochemical environment that supports a more balanced and tolerant immune response, thereby reducing the chronic inflammation that drives autoimmune symptoms and long-term tissue damage.

Intermediate

Advancing from the foundational knowledge of hormones, we can now examine the specific mechanisms through which hormonal optimization protocols interact with the autoimmune process. This involves a more granular look at how adjusting hormone levels can change the behavior of the immune system at a cellular level.

The core principle is biochemical recalibration. We are aiming to adjust the internal signaling environment to favor immune resolution over persistent inflammation. This requires precise, individualized protocols that account for the specific autoimmune condition, the person’s sex, and their unique hormonal landscape as revealed by comprehensive lab work.

How Do Hormones Talk to Immune Cells?

Immune cells have receptors on their surfaces that act like docking stations for hormones. When a hormone like testosterone or estrogen binds to its receptor, it triggers a cascade of events inside the cell, altering its function and gene expression. This is the direct line of communication between the endocrine and immune systems.

For instance, estrogen can bind to B-cells, a type of immune cell, and stimulate them to produce more antibodies, which can include the autoantibodies that attack the body’s own tissues in conditions like lupus. Conversely, testosterone can bind to T-cells, another key immune cell type, and promote their differentiation into regulatory T-cells (Tregs). Tregs are the “peacekeepers” of the immune system, responsible for shutting down excessive immune responses and preventing autoimmunity.

The interaction between hormones and their specific receptors on immune cells directly alters cellular behavior and inflammatory signaling.

Clinical Protocols in an Autoimmune Context

Applying this knowledge requires carefully designed therapeutic protocols. The standard protocols for hormone optimization must be adapted with special consideration for the autoimmune patient. The long-term safety of these interventions hinges on this careful, monitored approach.

For men with an autoimmune condition and clinically low testosterone, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is a primary consideration. The protocol often involves weekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injections of Testosterone Cypionate. This approach is designed to restore testosterone’s natural immunomodulatory effects.

By maintaining stable, optimal levels of testosterone, the protocol aims to decrease the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha and IL-6, which are major drivers of inflammation in conditions like Rheumatoid Arthritis. The inclusion of medications like Gonadorelin helps maintain the body’s own hormonal signaling pathways, supporting a more integrated systemic response. Anastrozole may be used judiciously to prevent the conversion of testosterone into estrogen, thereby avoiding the introduction of a potentially pro-inflammatory signal.

For women, the approach is more complex due to the fluctuating nature of the menstrual cycle and the transition of menopause. For a woman with an autoimmune condition, low-dose Testosterone Cypionate can be used to reintroduce the immunomodulatory benefits of androgens. Progesterone therapy is also a key component, particularly for its immune-calming effects.

The choice of protocol depends heavily on the individual’s menopausal status and specific condition. For instance, in Rheumatoid Arthritis, hormone therapy does not appear to increase disease flares and may even improve symptoms. In Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, the data suggests a small increased risk of mild to moderate flares with certain types of hormone therapy, necessitating a more cautious approach and a deep conversation about risks and benefits with the patient.

Comparing Hormonal Influences on Autoimmune Conditions

The decision to use hormone optimization is deeply dependent on the specific autoimmune disease in question. The table below outlines the general influence of key hormones on two common autoimmune conditions, based on current clinical understanding.

| Hormone | Influence on Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | Influence on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | Variable; some evidence suggests post-menopausal HRT does not worsen and may improve disease activity. | Generally immunoenhancing; may increase risk of mild to moderate flares, historically used with caution. |

| Testosterone | Generally protective; low levels are associated with higher disease risk and severity. TRT may reduce inflammatory markers. | Generally immunosuppressive; may inhibit B cell hyperactivity and offer a protective effect. |

| Progesterone | Anti-inflammatory; pregnancy-level rises are associated with remission of symptoms. | Immunomodulatory; may suppress certain pathways involved in SLE activity. |

What Are the Long Term Monitoring Requirements?

Long-term safety is contingent upon a partnership between the patient and the clinical team. It is a process of continuous monitoring and adjustment. This involves regular laboratory testing to ensure hormone levels remain within the optimal therapeutic window and to track markers of inflammation and immune function. Key monitoring practices include:

- Baseline and Follow-Up Labs ∞ Comprehensive panels that measure not just sex hormones, but also inflammatory markers (like C-reactive protein and ESR), and specific autoantibodies relevant to the condition.

- Symptom Tracking ∞ The patient’s subjective experience is a critical dataset. Detailed tracking of symptoms like pain, fatigue, and cognitive function helps correlate biochemical changes with quality of life.

- Risk Factor Management ∞ A significant long-term consideration is the risk of venous thrombosis (blood clots), which can be elevated with some forms of oral hormone therapy and in some autoimmune conditions like SLE. Using transdermal (patch) or injectable hormones can mitigate this risk. This must be assessed and managed proactively.

The long-term goal is to achieve a new state of equilibrium, where the immune system operates with greater tolerance and the body’s internal environment supports sustained well-being. This requires a sophisticated, adaptive, and deeply personalized approach to care.

Academic

An academic exploration of the long-term safety of hormonal optimization in autoimmune disease requires a deep dive into the molecular and cellular immunology of sex hormone action. The central thesis is that supraphysiological or restorative hormonal treatments do not merely act as blunt instruments of suppression, but as sophisticated modulators of immune cell lineage commitment, cytokine profiles, and the balance between autoreactive and regulatory immune populations.

The safety of such interventions is therefore a function of our ability to understand and predict these nuanced effects within the complex, dysregulated system of an autoimmune patient.

The Androgen-Mediated Regulation of T-Cell Subsets

A primary mechanism underpinning the therapeutic potential of testosterone in autoimmunity is its profound influence on the differentiation and function of CD4+ T-helper cells. The autoimmune state is often characterized by a dominance of pro-inflammatory T-helper 1 (Th1) and T-helper 17 (Th17) cells, which produce cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-17 (IL-17). These cytokines perpetuate tissue damage.

Testosterone, acting through the androgen receptor expressed on T-cells, can directly influence their fate. Research, including animal models of autoimmune disease, demonstrates that testosterone can suppress the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells. Concurrently, and perhaps more importantly for long-term safety and efficacy, testosterone promotes the expansion of a critical subset of immune cells known as CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells (Tregs).

Tregs are the master regulators of immune tolerance. They actively suppress the proliferation and function of self-reactive effector T-cells. An increase in the number and functional capacity of Tregs can restore a state of peripheral tolerance, which is the mechanism that prevents the immune system from attacking itself. Therefore, TRT in this context is a strategy to correct a deficiency in immunoregulation, aiming to increase the Treg/Th17 ratio, a key indicator of immune balance.

Testosterone directly promotes the expansion of regulatory T-cells, which are crucial for establishing and maintaining immune tolerance.

Impact on Cytokine Networks and B-Cell Activity

The immunomodulatory effects extend beyond T-cells. Androgens can significantly reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by macrophages and other innate immune cells. In experimental models of autoimmune orchitis, testosterone replacement was shown to decrease the testicular expression of mediators like MCP-1, TNF-α, and IL-6. This reduction in the inflammatory milieu has systemic benefits, lessening the overall state of chronic inflammation that contributes to fatigue, pain, and long-term organ damage.

Furthermore, androgens can directly inhibit B-cell hyperactivity. B-cells are responsible for producing antibodies, and in autoimmunity, they produce the autoantibodies that define many of these conditions. Studies in patients with SLE have shown that androgen treatment can inhibit immunoglobulin production by B-cells.

This provides a mechanistic rationale for the observed benefits of androgens in B-cell-driven diseases. The long-term safety consideration here is the degree of this inhibition. The goal is to normalize B-cell function, not to induce a state of broad immunosuppression that would increase susceptibility to infections.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal-Gonadal Axis Crosstalk

A systems-biology perspective reveals that the endocrine and immune systems are linked through complex feedback loops, particularly involving the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axes. Chronic inflammation, as seen in autoimmune disease, is a potent stressor that activates the HPA axis, leading to the release of cortisol.

While cortisol has acute anti-inflammatory effects, chronic activation can lead to glucocorticoid resistance and a dysregulation of the immune response. This chronic inflammatory state can also suppress the HPG axis, leading to hypogonadism (low testosterone) in men. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ inflammation suppresses testosterone, and low testosterone reduces immune regulation, leading to more inflammation.

Hormonal optimization can be seen as an intervention to break this cycle. By restoring gonadal hormone levels, it may help re-establish a more normal HPA-HPG axis balance, reducing the systemic stress response and its downstream consequences.

Potential Risks and Advanced Considerations

The academic view of safety requires acknowledging and investigating potential adverse outcomes with molecular precision. The table below summarizes key areas of academic inquiry regarding long-term safety.

| Area of Concern | Molecular and Cellular Mechanism | Long-Term Safety Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Thrombotic Risk | Oral estrogens can increase hepatic synthesis of clotting factors. Autoimmune conditions like SLE with antiphospholipid antibodies confer an independent prothrombotic state. | Utilize transdermal or injectable routes of administration to bypass first-pass liver metabolism. Thorough screening for underlying coagulopathies. |

| Disease Flare Activation | High levels of estrogen can promote Th2-skewed responses and B-cell activation, potentially tipping the immune balance and triggering a flare in susceptible individuals, particularly in SLE. | Careful dose titration, starting low and going slow. Preferentially using protocols that balance estrogen with progesterone and/or testosterone. Close monitoring of clinical and serological markers of disease activity. |

| Hormonal Oncogenesis | Prolonged, unopposed estrogen stimulation is a known risk factor for endometrial cancer. The relationship with breast cancer is more complex and dose/formulation dependent. The data on testosterone and prostate cancer risk is evolving but does not currently support a causal link with therapy that maintains physiologic levels. | Adherence to established screening guidelines (mammograms, PSA tests). Use of progesterone to oppose estrogen’s effect on the endometrium. Maintaining hormone levels within a safe, physiological range. |

In conclusion, the academic perspective frames long-term safety as a dynamic process of risk stratification and mitigation, grounded in a deep understanding of molecular immunology and endocrinology. It moves the conversation from a simple “is it safe?” to “for whom, under what conditions, and with what specific monitoring protocols can we maximize the immunoregulatory benefits while minimizing predictable risks?” This requires a commitment to personalized medicine and ongoing research to further elucidate these complex interactions.

References

- Holroyd, C. R. & Edwards, C. J. (2009). The effects of hormone replacement therapy on autoimmune disease ∞ rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Climacteric, 12(5), 378-386.

- Cutolo, M. & Wilder, R. L. (2000). The role of sex hormones in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America, 26(4), 825-839.

- Fijak, M. et al. (2011). Testosterone Replacement Effectively Inhibits the Development of Experimental Autoimmune Orchitis in Rats ∞ Evidence for a Direct Role of Testosterone on Regulatory T Cell Expansion. The American Journal of Pathology, 179(5), 2392-2402.

- Hughes, G. C. & Choubey, D. (2014). Progesterone and autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity Reviews, 13(4-5), 502-511.

- Sahin, S. et al. (2004). The effect of testosterone replacement treatment on immunological features of patients with Klinefelter’s syndrome. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 27(9), 827-832.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Map

You have now journeyed through the intricate connections between your hormonal state and your immune system. This information is more than a collection of scientific facts; it is a set of tools for self-understanding. The feelings of change you experience in your body are not random noise; they are signals from a complex, interconnected system.

Viewing your health through this lens allows you to move from a position of passive endurance to one of active inquiry. What is your body communicating? How do your internal rhythms intersect with your well-being?

This knowledge forms the basis for a new kind of conversation, one that you can have with yourself and with your clinical team. It equips you to ask more precise questions and to understand the rationale behind potential therapeutic paths. The journey toward reclaiming vitality is a personal one, built on a foundation of deep biological knowledge.

Your unique physiology and your personal health goals are the most important coordinates on this map. The path forward is one of collaboration, monitoring, and a sustained commitment to listening to the profound dialogue within your own body.