Fundamentals

Your journey into understanding your body’s intricate hormonal systems often begins with a question, a symptom, or a feeling that something has shifted. You may be experiencing changes in energy, mood, or vitality, and in seeking answers, you have encountered the topic of androgen therapy, specifically testosterone, for women.

This exploration is a profound step toward reclaiming your biological sovereignty. The question of long-term safety, particularly for the health of your uterine lining, the endometrium, is a critical and intelligent one. It reflects a deep respect for your body and a desire to make informed, empowered decisions. Let us approach this topic together, building a foundation of knowledge that honors your experience and illuminates the science behind it.

The endometrium is a remarkably dynamic and responsive tissue. It is the innermost layer of the uterus, a landscape that changes throughout the menstrual cycle under the precise direction of hormonal signals. Think of it as a carefully tended garden, where different hormones act as master gardeners, each with a specific role.

The health of this garden depends on a delicate and collaborative dialogue between these powerful molecules. To understand the long-term effects of any hormonal therapy, we must first appreciate the natural conversation that is constantly occurring within this tissue. The primary voices in this conversation belong to estrogen, progesterone, and androgens.

The Architect of Growth Estrogen’s Role

Estrogen is the principal architect of the endometrium. During the first half of the menstrual cycle, rising estrogen levels send a signal for the endometrial lining to grow, thicken, and proliferate. It builds the foundation, creating a lush, receptive environment. This proliferative effect is essential for fertility and normal cyclic function.

Estrogen instructs the cells to multiply, increasing the thickness of the lining and developing the glands and blood supply necessary to support a potential pregnancy. This is a healthy, vital process when it occurs in its proper time and in balance with its hormonal counterparts.

The body’s wisdom is reflected in this preparatory phase, where potential is carefully built and nurtured. This estrogen-driven growth is a fundamental aspect of female physiology, a testament to the body’s innate capacity for renewal.

The Master Regulator Progesterone’s Influence

Following ovulation, the hormone progesterone enters the conversation, and its voice changes the entire dynamic. Progesterone is the master regulator, the force of maturation and stability. Its primary role is to oppose estrogen’s proliferative signal. It halts the growth of the endometrial lining and shifts its function from building to maturing.

Progesterone causes the endometrial cells to differentiate, becoming secretory and stable. This prepares the uterus for implantation and is absolutely essential for maintaining a pregnancy. In a cycle where pregnancy does not occur, the withdrawal of progesterone is the signal that triggers the shedding of the endometrial lining, or menstruation.

This cyclical opposition to estrogen is a cornerstone of endometrial health. Progesterone ensures that the growth stimulated by estrogen is controlled, organized, and purposeful. Its presence protects the endometrium from the risks of unchecked cellular growth, maintaining order within the system.

The endometrium’s health relies on a balanced hormonal conversation, primarily between estrogen’s growth signals and progesterone’s stabilizing influence.

The Modulator Androgens in the Endometrial Ecosystem

Androgens, including testosterone, are the third voice in this conversation, acting as powerful modulators. While often associated with male physiology, androgens are indispensable for female health, contributing to libido, bone density, muscle mass, and overall well-being. Within the endometrium, androgens have their own distinct role.

The cells of the endometrium have specific docking sites, or receptors, for androgens, just as they do for estrogen and progesterone. This means that testosterone can communicate directly with the uterine lining. Some research suggests that direct androgenic signaling can have a balancing, or even anti-proliferative, effect on the endometrium, helping to temper estrogen’s growth signals. This adds another layer of complexity and elegance to the body’s regulatory systems.

A crucial aspect of androgen physiology in women is a process called aromatization. This is a natural biochemical conversion where an enzyme named aromatase transforms androgens, like testosterone, into estrogen. This happens in various tissues throughout the body, including fat cells and the ovaries.

Therefore, when considering testosterone therapy, we must account for two distinct effects on the endometrium. There is the direct effect of testosterone binding to its own receptors, and there is the indirect effect stemming from the portion of that testosterone that will be converted into estrogen.

This indirect effect is at the heart of the safety considerations for endometrial health. An increase in testosterone can lead to an increase in estrogen, which, if left unbalanced, can amplify the primary growth signal to the uterine lining. Understanding this conversion is fundamental to designing safe and effective hormonal optimization protocols.

Intermediate

Advancing our understanding of endometrial safety during androgen therapy requires us to move from the general roles of hormones to the specific mechanisms at play within the uterine lining. The clinical management and long-term stewardship of your health depend on a precise comprehension of how testosterone interacts with the endometrium, both directly and indirectly.

This knowledge empowers you and your clinician to create a protocol that provides the benefits of hormonal optimization while diligently safeguarding the health of your uterus. The core principle guiding this clinical approach is maintaining the balance between proliferative and stabilizing signals within the endometrium.

The Cellular Dialogue Androgen Receptors and Aromatization

The endometrial tissue is a complex environment where stromal cells (the connective tissue framework) and epithelial cells (the glandular lining) are in constant communication. Both of these cell types express androgen receptors (AR). When testosterone circulates through the bloodstream and reaches the uterus, it can bind to these receptors, initiating a direct cellular response.

Some in-vitro studies and clinical observations suggest that direct AR activation may have an anti-proliferative effect, potentially counteracting some of estrogen’s growth-promoting activity. This creates a sophisticated system of checks and balances at the local tissue level.

However, the more significant consideration in long-term therapy is the indirect pathway of aromatization. When testosterone is administered, a portion of it is converted to estradiol, a potent form of estrogen. This conversion effectively increases the total estrogenic load on the body.

If this additional estrogen is not balanced by a sufficient progestogenic signal, it can lead to unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium. This state of unopposed estrogen is the primary mechanism of concern. It can cause the endometrial lining to continue proliferating beyond its normal cyclical pattern, leading to a condition known as endometrial hyperplasia.

This condition represents a spectrum of changes, from simple, benign overgrowth to more complex and atypical changes that are considered precancerous. Therefore, the central pillar of ensuring endometrial safety during androgen therapy for any woman with a uterus is the principle of progestogen opposition.

What Is the Role of Progestogen Opposition?

Progestogen opposition is the clinical practice of co-administering a progesterone or a synthetic progestin alongside any hormone therapy that could increase estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium. The progestogen’s function is to mimic the natural luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, providing the necessary “stop growing and mature” signal to the uterine lining.

It induces secretory changes in the glands, stabilizes the stroma, and ultimately controls proliferation. This action effectively prevents the development of endometrial hyperplasia and significantly reduces the long-term risk of endometrial cancer. The choice of progestogen, its dose, and its schedule (cyclic or continuous) are tailored to the individual’s menopausal status, specific protocol, and personal health history.

- Micronized Progesterone This is a bioidentical form of the hormone, meaning it is structurally identical to the progesterone the body produces naturally. It is often favored for its favorable metabolic profile and lower incidence of certain side effects. It is typically administered orally at bedtime, as it can have a sedative effect that aids sleep.

- Synthetic Progestins These are man-made molecules designed to bind to and activate progesterone receptors. Examples include medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and levonorgestrel. Levonorgestrel is commonly used in hormonal intrauterine devices (IUDs), which provide a highly effective, localized progestogenic effect directly to the endometrium with minimal systemic absorption. This makes it an excellent option for endometrial protection.

Clinical Monitoring and Surveillance Protocols

A proactive and vigilant approach to monitoring is essential for ensuring long-term endometrial safety. This involves a partnership between you and your clinical team, utilizing established diagnostic tools to periodically assess the health of your uterine lining. This surveillance is a standard part of care for women on hormone therapy.

Consistent clinical monitoring, including transvaginal ultrasound and, when necessary, endometrial biopsy, is the standard of care for ensuring endometrial safety.

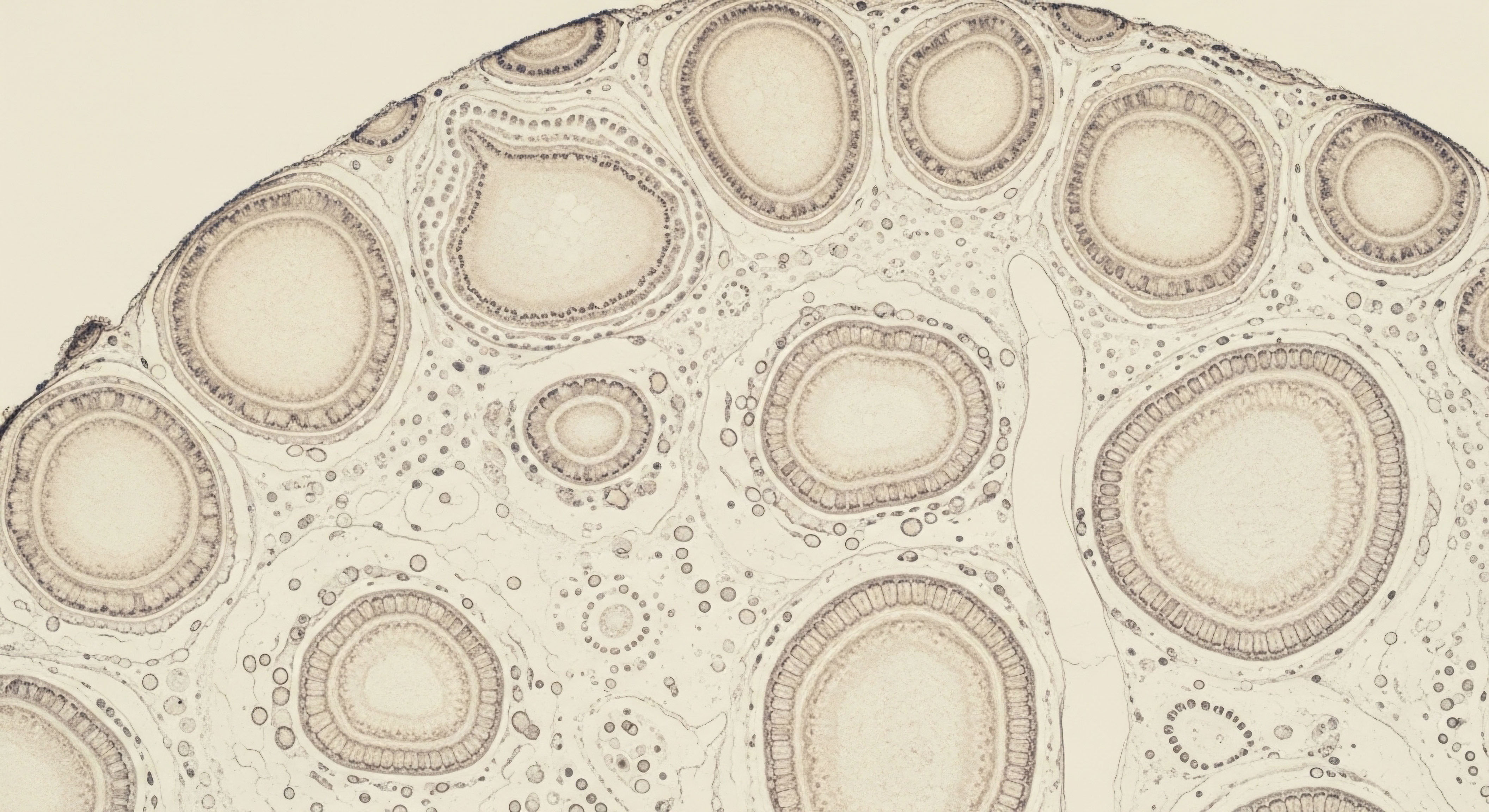

The primary screening tool is the transvaginal ultrasound. This is a simple, non-invasive imaging procedure that uses sound waves to create a clear picture of the uterus. The main measurement of interest is the endometrial thickness, often referred to as the “endometrial stripe.” In postmenopausal women, a thin endometrial stripe is expected.

A thickened stripe, generally considered to be above 4 or 5 millimeters in a postmenopausal woman, can indicate endometrial proliferation and may warrant further investigation. For pre-menopausal or peri-menopausal women, the expected thickness varies depending on the phase of the menstrual cycle, a detail your clinician will interpret in context.

If an ultrasound reveals a thickened endometrial lining, or if a woman experiences any unscheduled or abnormal uterine bleeding, the next step is typically an endometrial biopsy. This is a safe, office-based procedure where a very small sample of the endometrial tissue is collected for analysis.

A pathologist examines the cells under a microscope to determine their structure and rule out the presence of hyperplasia or more serious changes. While the procedure can cause some temporary cramping, it provides definitive, invaluable information about the state of the endometrium at a cellular level.

| Technique | Description | Primary Purpose | Key Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transvaginal Ultrasound | A non-invasive imaging technique using a small ultrasound probe placed in the vagina to visualize the uterus and ovaries. | Screening for endometrial thickening. It is the first-line assessment tool. | Endometrial Stripe Thickness (e.g. >4-5 mm in postmenopausal women). |

| Endometrial Biopsy | An in-office procedure where a thin, flexible tube is inserted through the cervix to suction a small sample of endometrial tissue. | Diagnostic evaluation of the endometrial cells to identify hyperplasia or malignancy. | Histopathological findings (cellular structure and organization). |

| Saline-Infusion Sonohysterography | An enhanced ultrasound where a small amount of sterile saline is infused into the uterine cavity to provide a clearer image of the lining. | To better characterize abnormalities seen on a standard ultrasound, such as polyps or fibroids. | Detailed visualization of the uterine cavity’s shape and any focal lesions. |

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the long-term endometrial safety of androgen therapy requires a deep dive into the molecular biology of the endometrium and a critical appraisal of the existing clinical evidence. From an academic perspective, the conversation shifts to the intricate interplay of nuclear receptor signaling, cell cycle regulation, and the specific genetic programs activated or suppressed by different hormonal ligands.

The central question evolves from “is it safe?” to “by what mechanisms can we ensure safety, and how can we stratify risk based on individual molecular profiles?” The available literature, while still lacking large-scale, long-term randomized controlled trials, provides significant mechanistic insights that guide expert clinical practice.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hormonal Action in Endometrial Cells

The endometrium’s response to sex steroids is mediated by the activation of their cognate nuclear receptors ∞ the estrogen receptor (ER), the progesterone receptor (PR), and the androgen receptor (AR). These receptors are ligand-activated transcription factors that, upon binding to their respective hormones, translocate to the cell nucleus and bind to specific DNA sequences known as hormone response elements (HREs).

This action modulates the transcription of target genes, thereby orchestrating the cell’s response. The long-term safety of androgen therapy hinges on the net effect of signaling through these three receptor pathways.

The primary concern, unopposed estrogenic stimulation, leads to the upregulation of genes that promote cell cycle progression and proliferation, such as c-myc and cyclin D1. This is mediated primarily through ER-alpha, the predominant estrogen receptor subtype in the endometrium responsible for proliferative effects.

Progesterone, acting through the PR, counteracts this by upregulating genes that inhibit cell cycle progression (e.g. p21, p27) and promote cellular differentiation and apoptosis (programmed cell death). This anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic effect is the molecular basis of progestogen-mediated endometrial protection.

How Does Androgen Receptor Signaling Modulate Endometrial Function?

The role of the androgen receptor in this triad is an area of active research with compelling findings. AR is expressed in both the stromal and epithelial cells of the endometrium. Some evidence suggests that AR activation can exert an anti-proliferative effect, opposing estrogen-driven growth.

For instance, studies have shown that androgens can inhibit the growth of endometrial cancer cell lines in vitro. Furthermore, there is a fascinating interplay between the PR and AR pathways. Research has demonstrated that treatment with progesterone antagonists (like mifepristone) leads to a significant upregulation of AR expression in the endometrium.

This suggests a reciprocal regulatory relationship where the blocking of progesterone signaling may sensitize the endometrium to androgenic effects. This complex crosstalk implies that the hormonal balance within the endometrium is a finely tuned network where the activity of one receptor can influence the expression and function of another. It is this integrated system, not a single hormone-receptor interaction, that determines the ultimate tissue response.

Evaluating the Clinical Evidence and Risk Stratification

The clinical evidence regarding androgen therapy and endometrial cancer risk is complex. Large epidemiological studies have identified high levels of endogenous androgens as a risk factor for endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women. This association is largely believed to be driven by the aromatization of androgens to estrogens in peripheral adipose tissue, particularly in the context of obesity, which is itself a major risk factor. This highlights the importance of the indirect, estrogen-mediated pathway.

In contrast, studies on exogenous testosterone therapy have not shown a clear increase in endometrial cancer risk, particularly when administered in physiologic doses and with appropriate progestogen opposition. A 2004 study published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism evaluated the short-term effects of testosterone treatment on postmenopausal women.

The study found that testosterone alone did not stimulate endometrial proliferation. Moreover, when combined with estrogen, testosterone appeared to partially counteract the estrogen-induced proliferation. This finding supports the hypothesis that direct AR activation may have an anti-proliferative or balancing effect. However, the authors and subsequent clinical guidelines stress that these are short-term findings and long-term safety data are still needed.

The molecular safety of androgen therapy rests on ensuring progestogenic signals are sufficient to counteract the total proliferative stimulus from both endogenous and exogenous estrogen sources.

The critical takeaway from the academic literature is that the risk is not from testosterone itself, but from the potential for unopposed estrogenic stimulation resulting from its aromatization. Therefore, risk stratification becomes paramount.

A woman’s individual risk profile depends on factors such as her body mass index (as adipose tissue is a primary site of aromatization), her baseline hormonal status, the dose of testosterone administered, and, most importantly, the adequacy of the opposing progestogen regimen. For a woman with a uterus, the co-prescription of a progestogen is not merely an option; it is a clinical necessity rooted in the fundamental molecular biology of the endometrium.

| Hormonal Signal | Primary Receptor | Molecular Effect on Endometrium | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | Estrogen Receptor (ERα) | Upregulates genes for cell cycle progression (e.g. cyclins, c-myc), leading to cellular proliferation. | Unopposed stimulation increases risk of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. |

| Progesterone | Progesterone Receptor (PR) | Downregulates ER expression, upregulates cell cycle inhibitors (e.g. p21), and promotes cellular differentiation and apoptosis. | Opposes estrogen’s proliferative effects, providing endometrial protection. Essential for women with a uterus on estrogen or therapies that increase estrogen. |

| Androgen (Testosterone) | Androgen Receptor (AR) | Direct effects may be anti-proliferative. Indirect effects occur via aromatization to estradiol, increasing the total estrogenic stimulus. | The primary safety concern is the indirect estrogenic effect, mandating progestogen co-therapy. Long-term direct effects require further study. |

- Aromatization as the Key Variable The conversion of exogenous testosterone to estradiol is the most critical factor for endometrial health. The rate of this conversion can vary based on individual genetics, age, and particularly, the amount of adipose tissue.

- The Mandate for Progestogen Opposition For any woman with an intact uterus receiving a therapy that increases the systemic estrogenic load, concurrent progestogen administration is the standard of care to mitigate the risk of endometrial hyperplasia. This is a non-negotiable principle of safe practice.

- The Need for Long-Term Surveillance Given the absence of multi-decade studies, ongoing clinical monitoring through methods like transvaginal ultrasound and prompt evaluation of any abnormal bleeding remains a cornerstone of long-term management. This vigilance ensures that any changes in the endometrium are detected early.

References

- Slayden, O D, and R L Brenner. “Progesterone antagonists increase androgen receptor expression in the rhesus macaque and human endometrium.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 87, no. 6, 2002, pp. 2678-89.

- Wierman, Margaret E. et al. “Androgen Therapy in Women ∞ A Reappraisal ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 99, no. 10, 2014, pp. 3489-510.

- O’Mara, Tracy A. and Dylan J. Glubb. “Testosterone may be the key to treating endometrial cancer.” Technology Networks, 25 Aug. 2023.

- Zang, H. et al. “Effects of Testosterone Treatment on Endometrial Proliferation in Postmenopausal Women.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 89, no. 7, 2004, pp. 3459-64.

- Davis, Susan R. and R. J. Baber. “Androgen replacement in women ∞ a commentary.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 84, no. 6, 1999, pp. 1876-81.

- “Androgen Therapy in Women.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 94, no. 1, 2019, pp. 134-150.

- Khorram, O. et al. “Effects of testosterone plus estrogen on endometrial receptivity in postmenopausal women.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 77, no. 4, 2002, pp. 783-90.

- Dimitrakakis, C. et al. “Estrogen and progestin effects on the female breast.” Hormone and Metabolic Research, vol. 38, no. 12, 2006, pp. 745-53.

Reflection

You have now journeyed through the intricate biological landscape of the endometrium, exploring the cellular conversations that define its health. You have seen how estrogen builds, progesterone stabilizes, and how androgens modulate this delicate system. This knowledge is more than a collection of facts; it is a lens through which you can view your own body with greater clarity and appreciation.

The information presented here illuminates the mechanisms that responsible clinicians consider when designing personalized hormone protocols. It demystifies the process, transforming abstract risks into understandable biological pathways that can be monitored and managed.

This understanding is the first, most powerful step in your ongoing health story. The path forward involves a collaborative partnership with a clinical guide who respects your intuition, listens to your experience, and applies this scientific knowledge to your unique physiology. Every woman’s body has its own history, its own genetic predispositions, and its own metabolic signature.

Therefore, your path to hormonal balance will be yours alone. As you move forward, carry this knowledge with you. Let it inform your questions, guide your decisions, and reinforce your confidence as you take an active, authoritative role in the stewardship of your own vitality.

Glossary

androgen therapy

uterine lining

menstrual cycle

aromatization

endometrial safety during androgen therapy

androgen receptors

endometrial hyperplasia

unopposed estrogen

endometrial safety during androgen

progestogen opposition

endometrial cancer

micronized progesterone

endometrial safety

transvaginal ultrasound

postmenopausal women

endometrial proliferation

androgen receptor

cell cycle progression