Fundamentals

The sensation of living under a persistent financial strain is a deeply personal experience, one that manifests as a quiet tension in the body long before it is recognized as a clinical concern. This is the reality of the wellness penalty ∞ a physiological tax levied on the body by the unceasing vigilance that financial insecurity demands.

Your body’s sophisticated survival architecture, designed for acute, immediate threats, is forced into a state of perpetual activation. This process begins in the brain, which perceives the chronic worry over bills, debt, or economic instability as an unending danger. This perception triggers a cascade down a critical signaling pathway known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is your body’s central stress response system, a finely tuned network connecting your brain to your adrenal glands.

In response to the perceived threat of financial stress, the HPA axis commands the release of cortisol, a primary stress hormone. In short, controlled bursts, cortisol is profoundly useful; it sharpens focus, mobilizes energy, and prepares you to confront a challenge.

When the stress is chronic, as financial strain so often is, the system never receives the signal to stand down. Cortisol levels remain persistently elevated, shifting the hormone from a tool for survival into an agent of systemic disruption.

This sustained hormonal pressure is the foundational mechanism of the wellness penalty, initiating a series of cascading effects that silently erode health from within. It is a biological response to a socioeconomic condition, a clear demonstration of how our external world becomes inscribed into our internal physiology.

The constant activation of the body’s stress response system due to financial worry is the primary driver of its long-term physiological cost.

The Architecture of the Stress Response

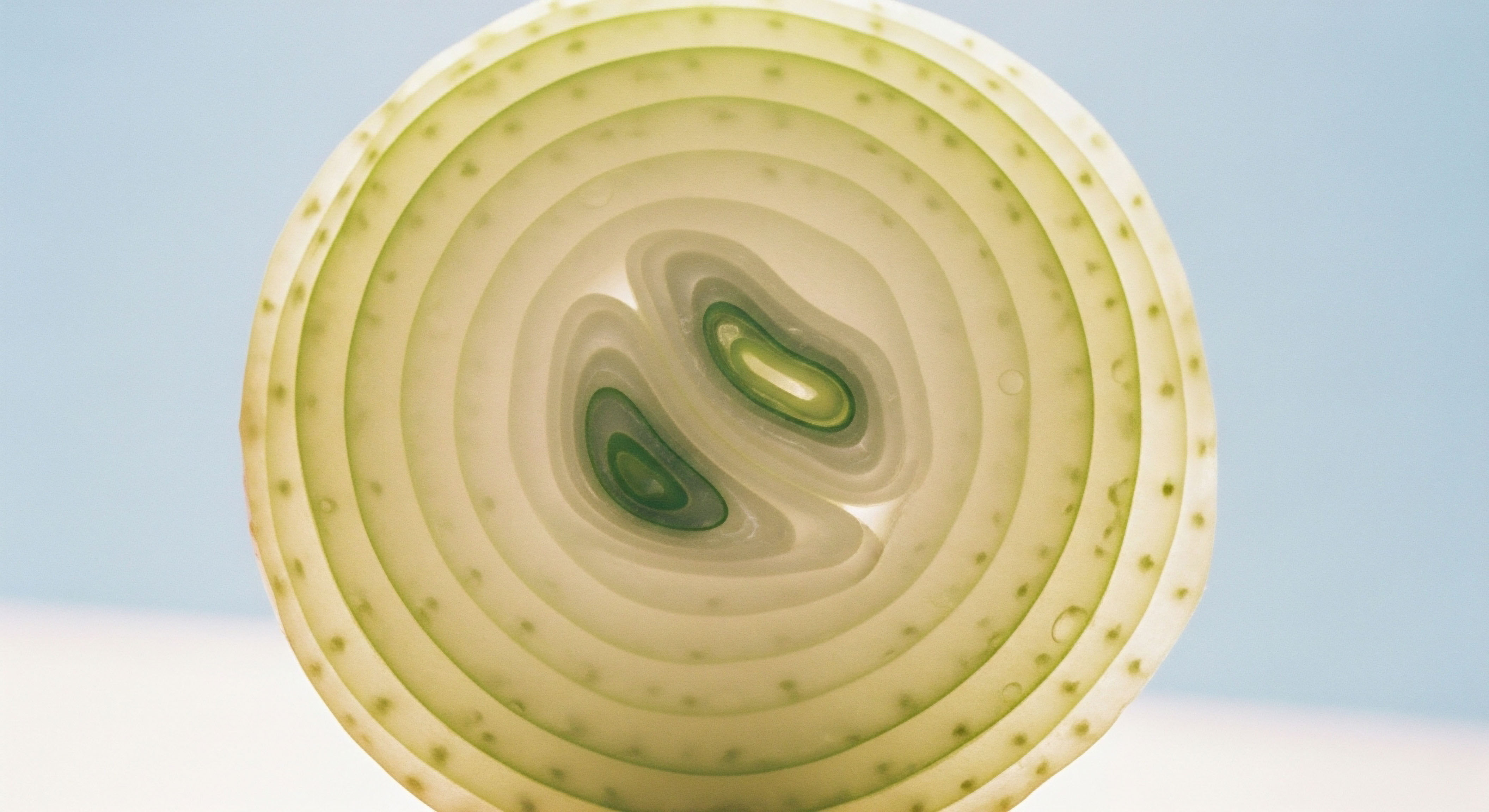

Understanding the body’s reaction to stress requires an appreciation for its elegant, yet vulnerable, design. The HPA axis functions as a command-and-control center. The hypothalamus, a small region at the base of the brain, acts as the initiator. When it detects a stressor, it releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH).

This hormone travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, stimulating it to secrete Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream. ACTH then journeys to the adrenal glands, situated atop the kidneys, instructing them to produce and release cortisol. This entire sequence unfolds with remarkable speed, equipping the body to handle an immediate crisis.

A crucial part of this design is a negative feedback loop; rising cortisol levels are supposed to signal the hypothalamus and pituitary to halt further production of CRH and ACTH, calming the system once the threat has passed.

Chronic financial stress effectively breaks this feedback loop. The threat never truly resolves, so the brain continues to signal for more cortisol. The body becomes marinated in a hormone that was meant for episodic use. This state of chronically elevated cortisol is what researchers refer to when they discuss the detrimental health effects of long-term stress.

It is the biological state where the adaptive nature of the stress response becomes maladaptive, creating the conditions for widespread physiological compromise. The systems intended to protect you are instead driven into a state of exhaustive overdrive.

What Happens When Cortisol Stays High?

Persistently high cortisol levels begin to alter the body’s internal environment in fundamental ways. Energy metabolism is one of the first systems to be affected. Cortisol’s primary role in a crisis is to ensure a ready supply of energy, which it achieves by increasing blood sugar levels.

When this state is prolonged, it can lead to sustained high blood sugar and promote the storage of visceral fat, particularly around the abdomen. This is a direct link between the abstract worry of financial insecurity and a tangible change in body composition and metabolic health.

Furthermore, the constant demand on the adrenal glands can lead to a state of dysregulation, where the natural rhythm of cortisol production ∞ typically highest in the morning and lowest at night ∞ is flattened, contributing to fatigue, sleep disturbances, and a feeling of being simultaneously “wired and tired.” This hormonal disruption is the first and most critical domino to fall in the long-term physiological consequences of chronic financial stress.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the initial activation of the HPA axis, the wellness penalty of chronic financial stress exerts profound and specific effects on the body’s interconnected hormonal and metabolic systems. The persistent elevation of cortisol acts as a powerful disruptor, silencing or altering the conversations between other critical endocrine networks.

One of the most significant casualties is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the system that governs reproductive and sexual health. The body, perceiving a state of perpetual crisis, begins to down-regulate functions it deems non-essential for immediate survival, including reproduction. High levels of cortisol can suppress the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which is the master signal for the entire reproductive cascade.

This suppression of GnRH leads to reduced secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) from the pituitary. These hormones are essential for signaling the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women ∞ to produce sex hormones.

In men, this can manifest as suppressed testosterone production, leading to symptoms of low energy, reduced libido, and difficulty maintaining muscle mass. In women, the disruption can be even more complex, leading to irregular menstrual cycles, impaired ovulation, and worsening of premenstrual or menopausal symptoms. The body is making a calculated, albeit detrimental, trade-off ∞ sacrificing long-term vitality for short-term survival.

How Does Stress Alter Hormonal Balance in Men and Women?

The impact of HPG axis suppression differs between the sexes due to their distinct hormonal environments. For men, the consequences center on the reduction of testosterone. For women, the interplay is more intricate, affecting the cyclical nature of estrogen and progesterone. The following table outlines these sex-specific effects.

| Hormonal System | Effects in Men | Effects in Women |

|---|---|---|

| HPG Axis Function |

Suppressed GnRH leads to lower LH and FSH, resulting in decreased testosterone production by the testes. |

Disrupted GnRH pulses lead to irregular LH and FSH release, causing anovulatory cycles and menstrual irregularities. |

| Primary Hormone Impact |

Lower total and free testosterone levels. |

Imbalanced estrogen-to-progesterone ratio and potential for estrogen dominance or deficiency. |

| Common Clinical Manifestations |

Fatigue, low libido, erectile dysfunction, loss of muscle mass, mood changes, and reduced motivation. |

Irregular or absent periods, worsened PMS, fertility challenges, and exacerbation of perimenopausal symptoms. |

The Road to Metabolic Syndrome

Simultaneously, the chronic cortisol exposure paves a direct path toward metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that dramatically increases the risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. This is not a random occurrence; it is a direct consequence of cortisol’s influence on energy storage and insulin signaling.

Chronic stress, particularly from financial strain, has been identified as a significant risk factor for developing this syndrome. The mechanism is multifaceted. Firstly, elevated cortisol promotes hyperglycemia by stimulating the liver to produce more glucose while simultaneously making muscle and fat cells less responsive to insulin ∞ a state known as insulin resistance.

The pancreas attempts to compensate by producing even more insulin, leading to high levels of both cortisol and insulin in the blood, a toxic combination that is highly effective at promoting visceral fat storage.

Chronic financial stress systematically dismantles metabolic health by promoting insulin resistance and the accumulation of dangerous visceral fat.

This process is compounded by stress-induced behaviors. Elevated cortisol can drive cravings for high-fat, high-sugar foods, which provide a temporary sense of comfort but further fuel the cycle of insulin resistance and fat storage. The components of metabolic syndrome are a direct reflection of this underlying pathophysiology.

- Abdominal Obesity ∞ A waist circumference greater than 40 inches for men and 35 inches for women, reflecting the accumulation of visceral fat driven by high cortisol and insulin.

- Hypertriglyceridemia ∞ Elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL), as the liver converts excess sugar into fat.

- Low HDL Cholesterol ∞ Reduced levels of “good” cholesterol (< 40 mg/dL in men, < 50 mg/dL in women), impairing the body's ability to clear cholesterol from the arteries.

- Elevated Blood Pressure ∞ Hypertension (≥ 130/85 mmHg), as cortisol and other stress hormones constrict blood vessels.

- Elevated Fasting Glucose ∞ High blood sugar (≥ 100 mg/dL) due to insulin resistance.

The presence of three or more of these criteria confirms a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, representing a significant escalation of the wellness penalty from a state of hormonal imbalance to one of active, high-risk disease.

Academic

The physiological consequences of chronic financial stress extend beyond endocrine disruption, culminating in a state of systemic, multi-system dysregulation known as allostatic overload. This framework describes how the cumulative burden of adapting to a persistent stressor like financial insecurity leads to widespread pathological changes.

The brain, as the central organ of the stress response, initiates and perpetuates this process, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of neurobiological, immunological, and cardiovascular damage. At the heart of this is the concept of glucocorticoid resistance, where immune cells, constantly exposed to high cortisol levels, become less sensitive to its anti-inflammatory signals.

This results in a paradoxical state ∞ despite high cortisol levels, the body enters a pro-inflammatory state, as the brakes on the immune system are effectively cut. This low-grade, chronic inflammation becomes a primary driver of the diverse pathologies associated with long-term stress.

Research has illuminated a specific neuro-immune pathway that links brain activity directly to cardiovascular risk. Studies using PET/CT imaging have shown that individuals with higher stress levels exhibit heightened metabolic activity in the amygdala, the brain’s fear and emotional processing center.

This increased amygdalar activity is directly correlated with increased bone marrow activity, leading to greater production of pro-inflammatory white blood cells. These cells then contribute to the development and instability of atherosclerotic plaques in the arteries, providing a direct mechanistic link between a perceived emotional threat and the physical reality of heart disease.

Financial stress, therefore, becomes a potent, independent risk factor for cardiovascular events, operating through pathways that are distinct from traditional risk factors like cholesterol or smoking, although it exacerbates them as well.

What Is the Ultimate Cellular Cost of This Process?

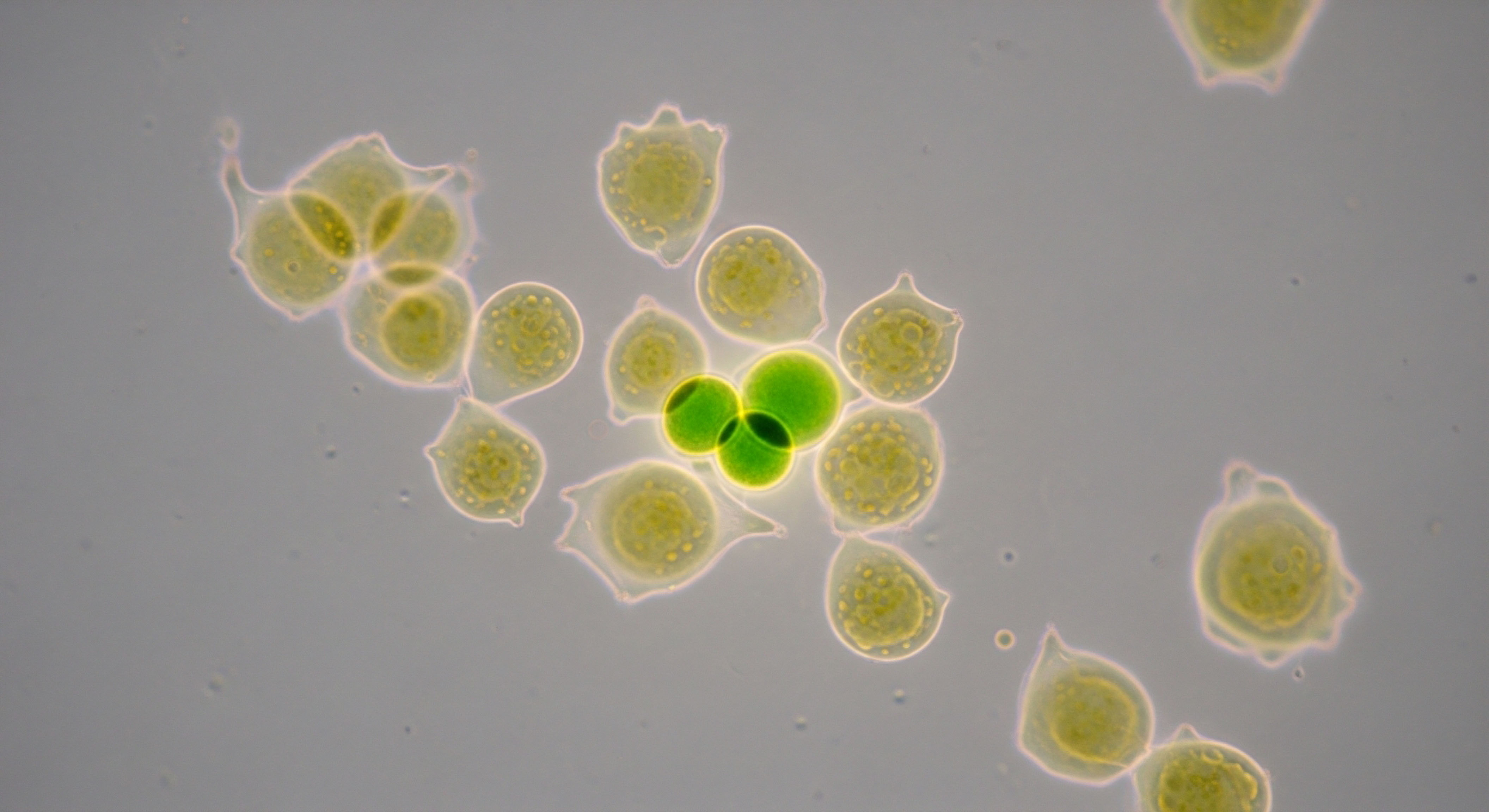

The ultimate biological toll of chronic financial stress is inscribed at the chromosomal level through the accelerated shortening of telomeres. Telomeres are the protective caps at the ends of our chromosomes that shorten with each cell division. Their length is a robust biomarker of cellular aging.

Chronic psychological stress is one of the most powerful predictors of accelerated telomere shortening. This process is driven by several of the mechanisms already discussed ∞ increased oxidative stress from a chronically activated metabolism and persistent inflammation both create a cellular environment that is hostile to telomere maintenance. The enzyme telomerase, which can replenish telomeres, is inhibited by chronic stress and high cortisol exposure.

Consequently, individuals under severe, long-term financial strain experience a faster rate of biological aging. Their cells reach a state of senescence, where they cease to divide, more quickly. These senescent cells do not simply die; they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, further contributing to the systemic inflammation that fuels age-related diseases.

This creates a devastating feedback loop ∞ stress drives inflammation, which accelerates cellular aging, and aging cells produce more inflammation. This convergence of neuro-immune dysregulation and accelerated cellular aging represents the most profound and insidious aspect of the wellness penalty.

A Systems-Level View of the Wellness Penalty

The long-term effects of chronic financial stress are best understood as a systems-level failure. It is a cascade of dysfunction that flows from the brain to the endocrine, immune, and cardiovascular systems, right down to the DNA within our cells. The table below synthesizes these interconnected pathological processes.

| System | Mechanism of Dysfunction | Physiological Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Neurobiological |

Chronic amygdala activation; dendritic remodeling in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. |

Heightened anxiety, impaired cognitive flexibility, mood disorders, and perpetuation of the stress response. |

| Immune |

Glucocorticoid receptor resistance and impaired negative feedback on immune cells. |

Chronic low-grade inflammation, increased susceptibility to infections, and potential for autoimmune flare-ups. |

| Cardiovascular |

Stress-induced hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, and increased inflammatory cell production. |

Accelerated atherosclerosis, increased plaque instability, and elevated risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. |

| Cellular |

Increased oxidative stress and inhibition of telomerase activity. |

Accelerated telomere shortening, premature cellular senescence, and a pro-inflammatory cellular environment. |

This integrated perspective reveals that financial stress is not merely a psychological burden. It is a potent biological agent that actively dismantles health across every level of human physiology, accelerating the aging process and precipitating the onset of chronic disease. The wellness penalty is the cumulative, biological price paid for living in a state of sustained economic uncertainty.

References

- Miller, G. E. Chen, E. & Parker, K. J. (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the common cold. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 165(11), 996 ∞ 1001.

- Cohen, S. Janicki-Deverts, D. Doyle, W. J. Miller, G. E. Frank, E. Rabin, B. S. & Turner, R. B. (2012). Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(16), 5995-5999.

- McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 1, 2470547017692328.

- Epel, E. S. Blackburn, E. H. Lin, J. Dhabhar, F. S. Adler, N. E. Morrow, J. D. & Cawthon, R. M. (2004). Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(49), 17312-17315.

- Tavsanli, H. & Ozturk, O. (2024). Stress and the Reproductive Axis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Investigations, 15(1), em01103.

- Kyrou, I. & Tsigos, C. (2009). Stress hormones ∞ physiological stress and regulation of metabolism. Current opinion in pharmacology, 9(6), 787 ∞ 793.

- Tawakol, A. Ishai, A. Takx, R. A. Figueroa, A. L. Ali, A. Kaiser, Y. & Levine, J. B. (2017). Relation between resting amygdalar activity and subsequent cardiovascular events. The Lancet, 389(10071), 834-845.

- Räikkönen, K. Matthews, K. A. & Kuller, L. H. (2007). The metabolic syndrome and stressful life events in a population-based sample of women. Diabetes care, 30(12), 3109-3115.

Reflection

From Knowledge to Action

The information presented here maps the biological consequences of a deeply human experience. Understanding that the anxiety rooted in financial uncertainty translates into measurable changes in your hormones, your metabolism, and even your chromosomes is a profound realization. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose.

It validates the physical toll of your lived experience, affirming that the fatigue, the brain fog, or the changes in your body are not imagined. They are the logical outcomes of a system under duress. This understanding is the critical first step.

The journey from this point forward is about translating this awareness into a personalized strategy, recognizing that restoring your body’s intricate balance is a process that requires a deliberate and guided approach. The path to reclaiming your vitality begins with acknowledging the depth of the connection between your life and your biology.

Glossary

wellness penalty

stress response

hpa axis

financial stress

cortisol

cortisol levels

chronic financial stress

high cortisol levels

visceral fat

hpg axis

metabolic syndrome

insulin resistance

chronic stress

glucocorticoid resistance

chronic inflammation

cellular aging

accelerated telomere shortening

cellular senescence