Fundamentals

You feel it deep within your cells. A persistent sense of being out of sync, a fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch, and a frustrating battle with your own body that seems to defy all your best efforts. This experience, this profound feeling of dysregulation, is a valid and biologically significant signal.

It speaks to a disruption in the most ancient and fundamental rhythm of your physiology, the circadian clock. Your body contains a magnificent internal timekeeping system, an intricate network of molecular clocks that governs nearly every aspect of your health. This system is designed to align your internal world with the external cycle of light and dark.

When this alignment is chronically broken, the consequences ripple through your entire being, starting with the very system that orchestrates your energy, mood, metabolism, and vitality ∞ your endocrine network.

Understanding the long-term physiological consequences of this disruption begins with appreciating the elegant architecture of your internal timing. At the system’s apex sits the master clock, a cluster of nerve cells in the brain’s hypothalamus known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN. The SCN functions as the central conductor of your biological orchestra.

It receives direct information about light from your eyes, using this primary cue to synchronize itself with the 24-hour day. From there, it sends out signals to coordinate a vast network of peripheral clocks located in virtually every organ and tissue of your body, including your liver, pancreas, muscles, and, critically, your endocrine glands.

These peripheral clocks are the individual sections of the orchestra, each designed to play its part at the correct time to create a cohesive physiological performance. The health of this entire system depends on the conductor and the musicians remaining in perfect time with one another.

The Rhythmic Nature of Hormones

Your endocrine system is the body’s primary communication network, using hormones as chemical messengers to regulate everything from your stress response to your reproductive function. This system does not operate with a constant, flat output. Instead, it is profoundly rhythmic, with hormone production and release carefully timed across the 24-hour cycle.

This temporal organization is essential for health. It ensures that metabolic processes are activated when you are likely to eat, that restorative processes are engaged when you are asleep, and that you have the hormonal drive to be alert and active during the day. Chronic circadian disruption throws this entire schedule into disarray.

It is akin to the conductor losing the beat, leaving the various sections of the orchestra to play at random, creating a cacophonic and dysfunctional state within the body.

The daily hormonal symphony is precise. Cortisol, the primary stress and alertness hormone, is designed to peak in the early morning, just before you wake. This surge helps you feel alert, mobilizes energy stores, and prepares you for the demands of the day.

As the day progresses, cortisol levels naturally decline, reaching their lowest point in the late evening to allow for the transition into sleep. Melatonin, the hormone of darkness, operates on an opposing schedule. Its production is suppressed by light and stimulated by darkness, with levels rising in the evening to promote sleep and initiate cellular repair processes.

Testosterone production in men also follows a distinct diurnal pattern, peaking in the morning to support drive, cognitive function, and physical performance. These are just a few examples of a system-wide, time-dependent organization that is vital for optimal function.

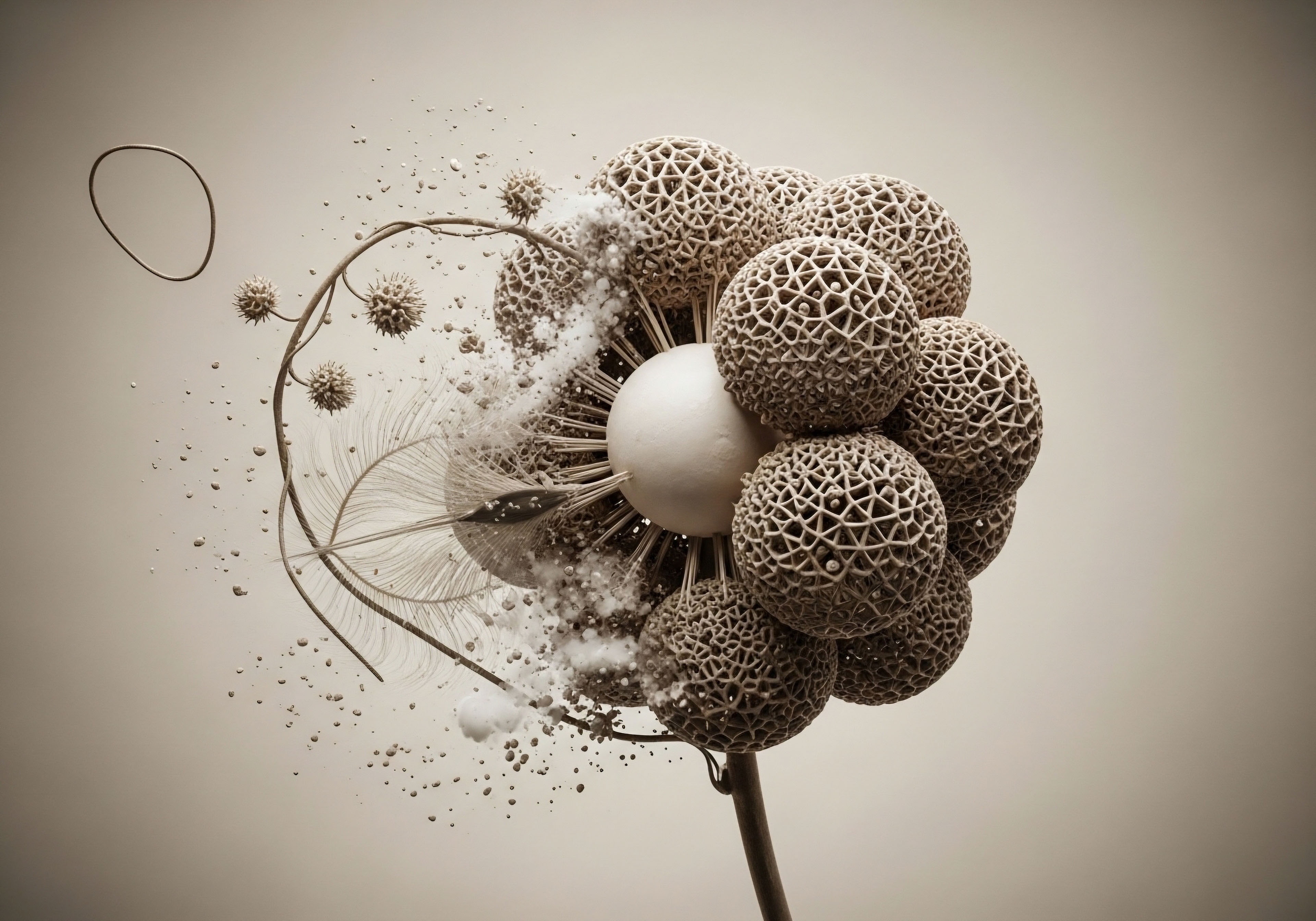

The body’s internal clocks are designed to synchronize hormonal release with the 24-hour cycle of day and night, a rhythm essential for physiological balance.

Key Endocrine Axes under Circadian Control

To appreciate the scale of the disruption, we must look at the major control centers of the endocrine system. These are known as axes, and they represent communication pathways between the brain and the peripheral endocrine glands. Three of the most important axes are profoundly influenced by the circadian system.

- The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis This is your central stress response system. The hypothalamus releases a hormone that signals the pituitary gland, which in turn signals the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. As mentioned, this axis has a powerful innate rhythm. Chronic circadian disruption, such as that caused by shift work or erratic sleep, can flatten this rhythm. This may lead to elevated cortisol levels at night, which interferes with sleep and promotes fat storage, and blunted cortisol levels in the morning, which contributes to profound fatigue and a lack of motivation. Over time, a dysregulated HPA axis is a primary driver of metabolic disease and chronic inflammation.

- The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis This axis governs reproductive function and the production of sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen. In men, the morning peak of testosterone is driven by circadian signals to the hypothalamus and pituitary. When this rhythm is disturbed, total testosterone production can decline, leading to symptoms of low testosterone, including fatigue, reduced libido, and difficulty maintaining muscle mass. In women, the HPG axis controls the menstrual cycle, a longer rhythm that is still influenced by daily circadian signals. Disruption can contribute to irregular cycles, worsening of premenstrual symptoms, and challenges with fertility.

- The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) Axis This system regulates your metabolism through the production of thyroid hormones. The release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) from the pituitary gland also follows a 24-hour pattern, typically peaking at night. Chronic disruption of this rhythm can alter the conversion of inactive thyroid hormone (T4) to active thyroid hormone (T3), leading to symptoms of sub-optimal thyroid function, such as weight gain, cold intolerance, and brain fog, even when standard lab tests appear to be within a normal range.

What Happens When the Clocks Are Misaligned?

Imagine your liver clock, which controls metabolic processes, is running on a different time zone from your SCN. This is precisely what happens when you eat a large meal late at night. Your SCN, sensing darkness, is preparing the body for sleep and fasting.

Your liver, however, is being forced into active duty by the arrival of nutrients. This conflict, known as internal desynchronization, is a core feature of circadian disruption. It creates a state of metabolic chaos. The pancreas is not prepared to release the optimal amount of insulin, the liver is not efficient at processing glucose, and fat cells become more prone to storing energy.

When this occurs day after day, year after year, it lays the groundwork for serious endocrine and metabolic consequences, including insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. This is the biological reality behind the feeling of being out of sync, a palpable and measurable dissonance within your own physiology.

Intermediate

The foundational understanding of a central clock and peripheral oscillators provides a map of the circadian system. Now, we examine the intricate mechanisms through which chronic desynchronization inflicts long-term damage upon the endocrine system. The consequences extend far beyond simple fatigue; they represent a systemic breakdown in metabolic and hormonal signaling, contributing directly to many of the chronic conditions prevalent today.

This process is driven by a persistent mismatch between the timing of our behaviors, such as light exposure, eating, and activity, and the genetically programmed rhythms of our internal clocks.

When the SCN, your master clock, perceives light at an inappropriate time, such as from a phone screen late at night, it sends a powerful signal that it is still daytime. This directly suppresses the production of melatonin from the pineal gland. This single event has cascading effects.

Melatonin is a potent antioxidant and a key regulator of sleep, but it also helps sensitize the body to insulin and modulates the release of reproductive hormones. Its chronic suppression creates a pro-inflammatory state and contributes to the metabolic dysregulation seen in shift workers and individuals with erratic schedules.

Simultaneously, this mistimed light information can disrupt the SCN’s ability to properly synchronize the peripheral clocks in your endocrine glands, leading to a state of internal chaos where different organ systems are operating on conflicting schedules.

Metabolic Derangement the Cortisol and Insulin Collision

One of the most immediate and damaging consequences of chronic circadian disruption is the deterioration of the relationship between cortisol and insulin. In a healthy, synchronized individual, the morning cortisol awakening response prepares the body for activity. It mobilizes glucose from the liver, ensuring the brain and muscles have ready fuel.

Insulin sensitivity is naturally higher during the daytime, meaning the body is highly efficient at using insulin to move glucose from the bloodstream into the cells after a meal. At night, as cortisol levels fall, insulin sensitivity decreases. This is a protective mechanism to maintain stable blood sugar during the overnight fast.

Chronic circadian disruption flips this system on its head. Stress from a misaligned lifestyle, erratic sleep, and late-night light exposure can lead to a flattened cortisol rhythm, with levels remaining elevated into the evening. This persistently high cortisol signal promotes a state of insulin resistance.

The body’s cells become less responsive to insulin’s message, forcing the pancreas to work overtime, pumping out more and more of the hormone to keep blood sugar in check. When you consume a meal, especially one high in carbohydrates, during this state of high cortisol and low insulin sensitivity at night, you create a perfect storm for metabolic damage.

The glucose from the meal floods the bloodstream and has nowhere to go efficiently. This leads to hyperglycemia, promotes the storage of fat, particularly visceral fat around the organs, and drives systemic inflammation. Over years, this process directly contributes to the development of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes.

How Does Circadian Disruption Affect Hormone Optimization Protocols?

For individuals undertaking hormonal optimization protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), understanding the circadian context is paramount for success. The goal of these therapies is to restore physiological balance and function. A disrupted circadian rhythm can work directly against these efforts.

For instance, a man on TRT may be administering testosterone to restore youthful levels, but if his cortisol is chronically elevated due to poor sleep and a misaligned schedule, he will struggle to achieve the full benefits.

High cortisol is catabolic, meaning it can break down muscle tissue, and it promotes fat storage, directly opposing the anabolic, muscle-building, and fat-reducing effects of testosterone. This is why a comprehensive approach to hormonal health must address the foundational pillar of circadian alignment.

Similarly, for women using hormonal therapies to manage perimenopausal or postmenopausal symptoms, circadian health is essential. The sleep disturbances, hot flashes, and mood swings common during this transition are often exacerbated by underlying circadian disruption. Restoring a robust rhythm through lifestyle interventions can significantly improve the efficacy of progesterone or low-dose testosterone therapy.

Progesterone, for example, has calming effects and can improve sleep quality, but its benefits are amplified when taken in an environment that supports the natural evening rise of melatonin and decline of cortisol.

The efficacy of hormone replacement therapies is deeply interconnected with the health of the body’s circadian rhythms, as hormonal signaling relies on a stable internal clock.

The Impact on Growth Hormone and Cellular Repair

Human Growth Hormone (GH) is another critical player with a strong circadian dependency. The vast majority of GH is released from the pituitary gland during the first few hours of deep, slow-wave sleep. This nightly pulse is a primary signal for cellular repair, muscle growth, bone density maintenance, and fat metabolism.

Chronic circadian disruption, which almost invariably leads to fragmented and poor-quality sleep, directly blunts this vital GH release. The long-term consequences are significant. They include accelerated aging (sarcopenia, or age-related muscle loss), increased body fat, reduced exercise capacity and recovery, and a general decline in vitality.

This is where peptide therapies find their clinical application. Peptides like Sermorelin, Ipamorelin, and CJC-1295 are secretagogues, meaning they signal the pituitary gland to produce and release its own GH. They are designed to mimic the body’s natural signaling molecules.

By administering these peptides before bed, the goal is to restore the natural, pulsatile release of GH that has been diminished by age or circadian disruption. This approach supports the body’s innate repair mechanisms, working with the circadian system to promote recovery and metabolic health. It is a targeted intervention designed to reinstate a specific, rhythmic hormonal process that has become dysfunctional.

The table below outlines the primary functions and typical timing of key hormones that are heavily regulated by the circadian system, illustrating the profound and widespread impact of its disruption.

| Hormone | Primary Function | Typical Peak Time | Consequence of Disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | Alertness, Stress Response, Glucose Mobilization | Early Morning (approx. 30 min after waking) | Morning fatigue, evening anxiety, insulin resistance, fat storage |

| Melatonin | Sleep Promotion, Antioxidant, Immune Modulation | Middle of the Night (in darkness) | Difficulty sleeping, increased inflammation, impaired cellular repair |

| Testosterone (Men) | Libido, Muscle Mass, Mood, Cognitive Function | Morning | Low libido, fatigue, depression, loss of muscle mass |

| Growth Hormone (GH) | Cellular Repair, Muscle Growth, Fat Metabolism | First Few Hours of Deep Sleep | Accelerated aging, increased body fat, poor recovery |

| TSH | Stimulates Thyroid Hormone Production | Night | Sub-optimal metabolism, weight gain, cold intolerance |

Disruption of the HPG Axis and Reproductive Health

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls reproductive health, is exquisitely sensitive to circadian timing. The pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus is the upstream driver of this entire system, and its rhythm is governed by the SCN. In men, this translates to the diurnal rhythm of testosterone.

Chronic disruption from shift work or sleep loss has been clearly shown in clinical studies to lower testosterone levels, sometimes to a degree comparable to aging ten to fifteen years. This can precipitate a need for interventions like TRT at a much earlier age.

In women, the situation is equally complex. The delicate interplay of hormones that governs the menstrual cycle, including Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), relies on a stable circadian backdrop. When this is disturbed, it can lead to a host of issues:

- Irregular Cycles The timing of ovulation can become unpredictable or cease altogether.

- Worsened PMS/PMDD The mood and physical symptoms associated with the premenstrual phase can be significantly amplified by cortisol dysregulation and poor sleep.

- Fertility Challenges A stable circadian rhythm is a key component of a healthy reproductive environment. Its disruption is a recognized contributor to difficulties with conception.

- Exacerbated Menopausal Symptoms The hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disturbances of perimenopause and menopause are all worsened by an unstable circadian system.

Addressing these issues requires a perspective that acknowledges the foundational role of circadian biology. Simply providing hormone replacement may be insufficient if the underlying temporal chaos is not also addressed through lifestyle and, in some cases, targeted therapies designed to support the body’s natural rhythms.

Academic

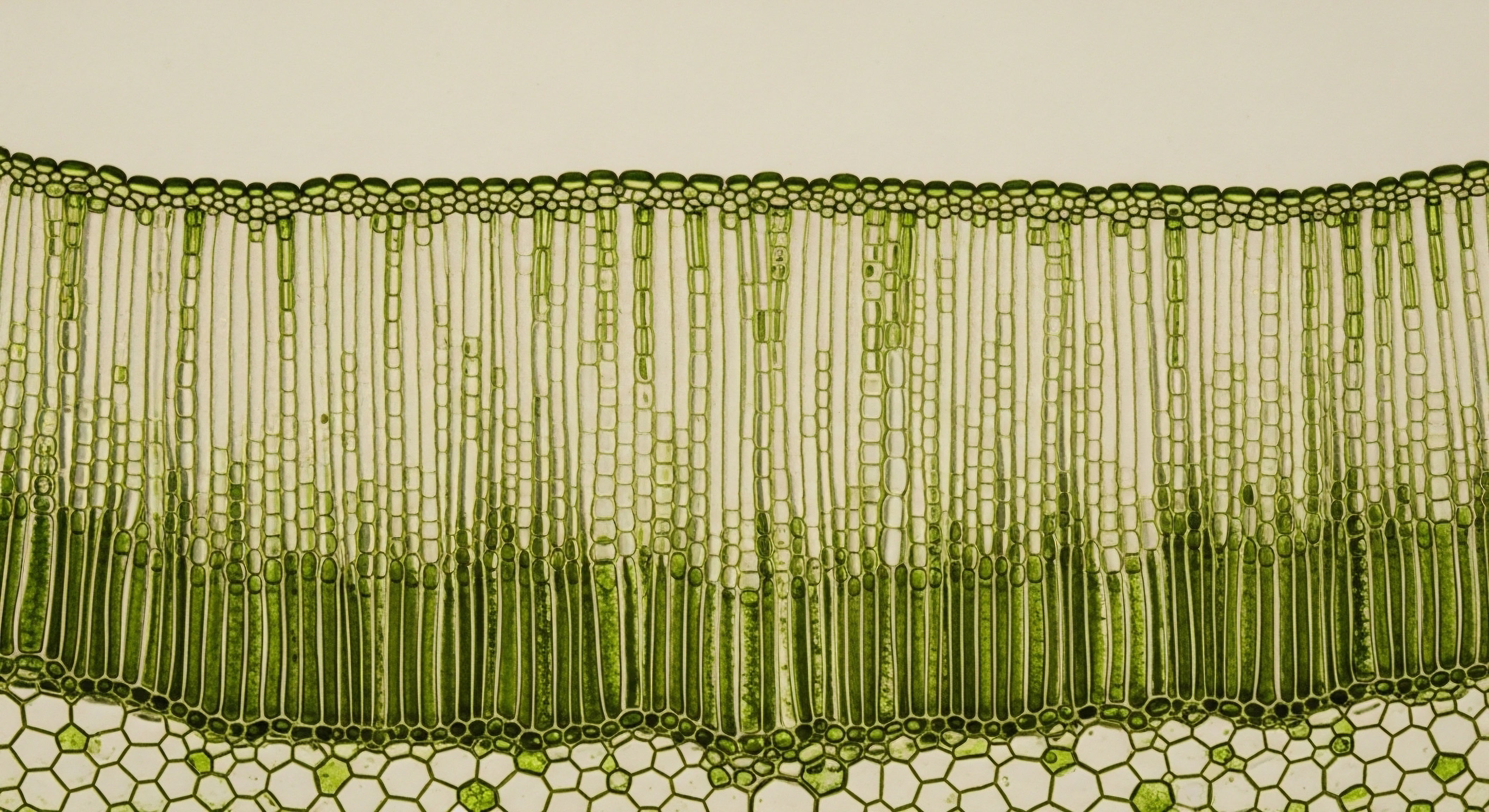

A sophisticated analysis of the long-term consequences of circadian disruption on endocrine health moves beyond systemic descriptions to the molecular level. The core of this pathology lies within the intricate machinery of the molecular clock itself, a transcription-translation feedback loop present in the SCN and every peripheral cell.

This cellular clockwork, composed of core clock genes such as CLOCK, BMAL1, Period (PER), and Cryptochrome (CRY), is not merely a timekeeper. It is a dynamic regulator of cellular metabolism and function, directly gating the expression of a significant portion of the proteome, including genes essential for hormone synthesis, secretion, and receptor sensitivity.

The canonical molecular clock mechanism involves the heterodimerization of the CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins. This complex binds to E-box enhancer elements in the promoter regions of target genes, initiating their transcription. Among these target genes are PER and CRY.

As the PER and CRY proteins accumulate in the cytoplasm, they form a complex, translocate back into the nucleus, and inhibit the activity of the CLOCK/BMAL1 complex. This act of self-repression turns off their own transcription, forming the negative feedback loop.

As the PER/CRY proteins degrade over a roughly 24-hour period, the inhibition is lifted, and the cycle begins anew. This elegant loop is the fundamental basis of cellular rhythmicity. Chronic circadian disruption, caused by a persistent mismatch between environmental cues (like light and food intake) and this internal clock, creates a state of forced desynchrony that induces profound molecular stress and pathological adaptations within endocrine tissues.

Molecular Disintegration in the Adrenal Gland

The adrenal gland provides a compelling case study of this molecular pathology. The synthesis of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol in humans, is under the direct transcriptional control of the molecular clock. The gene for steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), which facilitates the rate-limiting step of cholesterol transport into the mitochondria for steroidogenesis, contains E-box elements and is a direct target of CLOCK/BMAL1.

In a synchronized state, the morning peak of CLOCK/BMAL1 activity drives a robust transcription of StAR, leading to the cortisol awakening response. At night, as PER/CRY inhibition takes over, StAR expression is suppressed, and cortisol production wanes.

Under conditions of chronic circadian disruption, such as simulated shift work in laboratory models, this precise gating is lost. The adrenal peripheral clock becomes uncoupled from the SCN. This can lead to a tonic, low-level expression of StAR throughout the 24-hour cycle.

The result is a flattened cortisol rhythm, characterized by a blunted morning peak and elevated nocturnal levels. This altered secretory profile has devastating downstream effects. Persistently elevated nocturnal cortisol promotes visceral adiposity, suppresses immune function, and induces a state of chronic insulin resistance by interfering with GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle and promoting hepatic gluconeogenesis at an inappropriate time.

This molecular-level failure of temporal control within the adrenal gland is a primary driver of the metabolic syndrome phenotype associated with circadian misalignment.

How Does Clock Gene Disruption Affect Gonadal Steroidogenesis?

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal axis is similarly vulnerable at the molecular level. GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus exhibit rhythmic firing patterns under the control of their own intrinsic clocks. The downstream effectors, the Leydig cells in the testes and theca and granulosa cells in the ovaries, also possess functional peripheral clocks that regulate steroidogenic enzymes.

In males, studies using knockout mouse models where BMAL1 is selectively deleted in Leydig cells demonstrate a dramatic reduction in testosterone levels and impaired fertility, even with a functional HPG axis. This indicates that the local testicular clock is indispensable for normal steroidogenesis. It directly regulates the expression of key enzymes in the testosterone synthesis pathway, such as Cyp11a1 and Hsd3b.

Chronic jet lag or shift work simulates this genetic disruption by creating a functional desynchrony. The pituitary LH signal, driven by the SCN’s timing, may arrive at the Leydig cell at a time when the cell’s internal clock has down-regulated the necessary enzymatic machinery for testosterone production.

This mismatch between the endocrine signal and the target cell’s metabolic readiness leads to an inefficient and blunted hormonal response. Over the long term, this contributes to the progressive decline in androgen levels seen in men with chronically disrupted lifestyles. This explains why restoring circadian hygiene is a critical, yet often overlooked, component of managing male hypogonadism.

The molecular clocks within endocrine cells directly control the transcription of genes essential for hormone synthesis, making them a critical point of failure in circadian disruption.

The Interplay of Circadian Rhythms and Peptide Therapy

The science of peptide therapies for growth hormone optimization is deeply rooted in an understanding of circadian biology. The pulsatile release of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) from the hypothalamus, which stimulates the somatotrophs in the pituitary to release GH, is a circadian-gated process.

The efficacy of peptides like Sermorelin (a GHRH analogue) or the combination of Ipamorelin (a ghrelin mimetic and GHRP) and CJC-1295 (a long-acting GHRH analogue) depends on this underlying rhythm. These therapies are designed to amplify the natural, endogenous pulses of GH release. Their administration is timed, typically before bed, to coincide with the period of maximal natural somatotroph sensitivity and the onset of slow-wave sleep, where the largest GH pulse occurs.

From an academic perspective, these protocols are a form of chronotherapy. They are an attempt to restore a physiological rhythm that has been dampened by age and lifestyle factors. The molecular clock within the pituitary somatotrophs regulates the expression of the GHRH receptor.

A state of circadian disruption can lead to a down-regulation of this receptor, making the pituitary less responsive to both endogenous GHRH and exogenous peptide signals. This highlights a critical clinical point ∞ the success of GH peptide therapy may be significantly enhanced by concurrently implementing strategies to restore robust circadian rhythmicity, thereby maximizing the sensitivity of the target pituitary cells to the therapeutic signal.

The following table details the relationship between core clock genes and their influence on specific endocrine pathways, providing a glimpse into the molecular basis of circadian-driven health and disease.

| Clock Gene | Primary Molecular Function | Endocrine Pathway(s) Directly Regulated | Pathology of Disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMAL1 | Forms the positive arm of the clock with CLOCK; transcriptional activator. | Adrenal steroidogenesis (StAR), gonadal steroidogenesis (Cyp11a1), pancreatic insulin secretion. | Blunted cortisol rhythm, hypogonadism, glucose intolerance, diabetes. |

| CLOCK | Forms the positive arm with BMAL1; possesses histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity. | Regulates chromatin accessibility for other clock-controlled genes, influencing nearly all endocrine functions. | Widespread metabolic and endocrine dysregulation, implicated in mood disorders. |

| PER2 | Forms the negative arm of the clock; inhibits CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. | Glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, timing of cortisol suppression. | Elevated cancer risk, altered response to chemotherapy, sleep phase disorders. |

| CRY1/CRY2 | Forms the negative arm with PER; primary repressor of CLOCK/BMAL1. | Regulates the duration of the transcription cycle, influences insulin sensitivity. | Familial delayed sleep phase syndrome, insulin resistance. |

What Are the Broader Implications for Systemic Health?

The desynchronization of endocrine rhythms has consequences that extend into the immune and cardiovascular systems. Clock genes are present in all major immune cell populations, including macrophages and lymphocytes. The rhythmic expression of these genes controls the trafficking of immune cells and the production of cytokines.

Circadian disruption leads to a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state, characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-alpha. This inflammation is a key mechanistic link between circadian misalignment and a host of chronic diseases, including atherosclerosis, neurodegenerative conditions, and certain cancers.

The endocrine system, particularly the HPA axis, is a primary mediator of this process. The loss of the nocturnal dip in cortisol removes a key anti-inflammatory signal, allowing inflammatory processes to proceed unchecked throughout the night. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of disruption, inflammation, and further endocrine dysregulation, demonstrating the deeply interconnected nature of these physiological systems.

References

- Bedrosian, Tracy A. Laura K. Fonken, and Randy J. Nelson. “Endocrine Effects of Circadian Disruption.” Annual Review of Physiology, vol. 78, 2016, pp. 109-31.

- Morris, Christopher J. et al. “The Human Circadian System Has a Dominant Role in Regulating Diet-Induced Thermogenesis.” Obesity, vol. 23, no. 10, 2015, pp. 2053-58.

- Wehrens, S. M. T. et al. “Meal Timing Regulates the Human Circadian System.” Current Biology, vol. 27, no. 12, 2017, pp. 1768-1775.e3.

- Chellappa, Sarah L. et al. “Human Circadian Rhythms and the Sleep-Wake Cycle.” Medical Sciences, vol. 9, no. 4, 2021, p. 62.

- Gamble, Karen L. et al. “Shift Work in Nurses ∞ Contribution of Phenotypes and Genotypes to Adaptation.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 4, 2011, e18395.

- Salgado-Delgado, R. et al. “The Daily Meal Is a Time Cue for Circadian Gene Expression in the Pancreas.” Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 204, no. 3, 2010, pp. 233-41.

- Leproult, R. et al. “Impact of Sleep and Food Intake on Endocrine and Metabolic Function.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 99, no. 9, 2014, pp. E1435-41.

- Knutson, Kristen L. and Eve Van Cauter. “Associations between Sleep, Circadian Rhythm, and Metabolism ∞ A Review of the Evidence.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 93, no. 11_supplement_1, 2008, pp. s42-s47.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Internal Universe

The information presented here provides a biological blueprint, connecting the subjective feeling of being out of sync to the objective reality of endocrine and metabolic dysfunction. It validates your experience, grounding it in the elegant yet fragile science of our internal clocks. This knowledge is the first, most crucial step.

It transforms the conversation from one of managing disparate symptoms to one of restoring a fundamental, system-wide rhythm. Your body is not a collection of independent parts; it is an integrated, interconnected whole, timed to the ancient pulse of the planet.

The path forward involves recognizing that your daily choices about light, food, and movement are powerful hormonal signals. They are instructions you give to your own physiology. The journey to reclaiming your vitality begins with learning to send the right signals at the right time, a process of conscious and deliberate recalibration. This understanding empowers you to become an active participant in your own health, moving with intention toward restoring the profound and quiet harmony that is your biological birthright.