Fundamentals

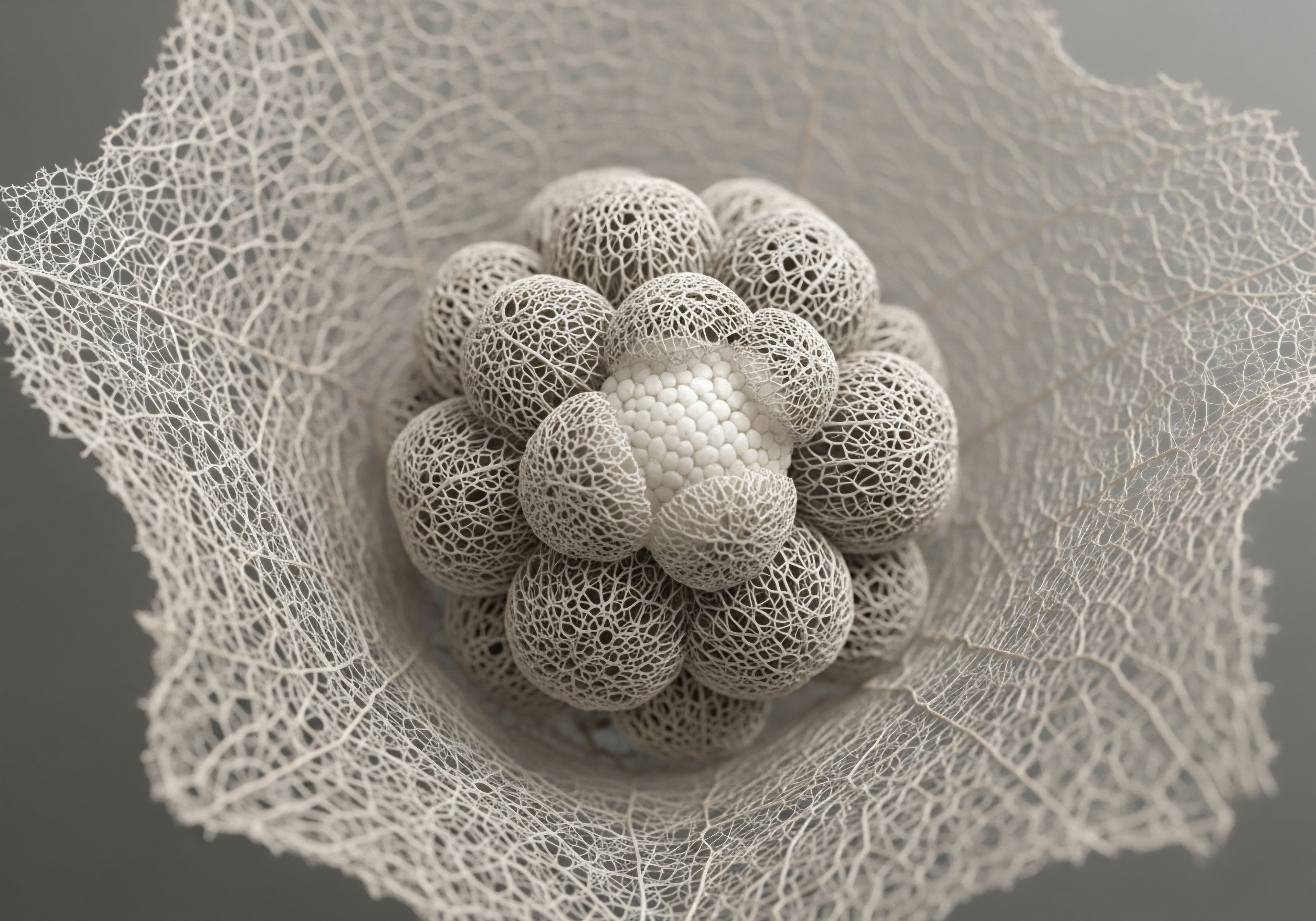

Living with endometriosis often means navigating a reality where the pain and symptoms extend far beyond the pelvic region. Your experience of fatigue, bloating, and a general sense of systemic imbalance is a valid and observable biological phenomenon. The conversation about this condition must begin with the understanding that endometriosis is a whole-body inflammatory state.

Its presence initiates a cascade of events that reverberates through your endocrine and metabolic systems, creating a unique physiological environment that demands a deeper level of understanding.

The core of this systemic impact lies in chronic, low-grade inflammation. The endometrial-like tissue located outside the uterus responds to monthly hormonal cycles, leading to bleeding and the release of pro-inflammatory signals called cytokines. Molecules such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) are released into your system.

These are not localized messengers; they circulate throughout the body, acting as a constant, low-level alarm for your immune system. This persistent inflammatory state is a primary driver of the broader metabolic disruptions you may be experiencing.

Untreated endometriosis creates a body-wide inflammatory environment that directly disrupts hormonal and metabolic balance.

Hormonal Crosstalk and Metabolic Signals

A key element in this process is the role of estrogen. Endometriosis is considered an estrogen-dependent condition, where the hormone promotes the growth of the lesions. This often leads to a state of relative estrogen excess. Estrogen is a powerful regulator of metabolic function, influencing how your cells respond to insulin and how your body processes fats.

When its levels are persistently high or imbalanced, it can begin to interfere with insulin signaling, making it harder for your cells to take up glucose from the blood. This is the first step toward insulin resistance, a foundational metabolic issue. The hormonal imbalance also directly alters lipid profiles, which can contribute to long-term cardiovascular risk.

What Are the Primary Drivers of Metabolic Shift?

The metabolic implications of untreated endometriosis are not a secondary symptom; they are a direct consequence of the disease’s underlying biology. The body’s resources are constantly diverted to manage the inflammation and hormonal dysregulation originating from the endometriotic lesions.

This chronic biological stress forces the metabolic system to adapt, leading to changes that can manifest as weight gain, difficulty managing blood sugar, and altered cholesterol levels. Understanding this connection is the first step in reclaiming control, moving the focus from managing isolated symptoms to addressing the systemic nature of the condition itself.

Intermediate

To fully grasp the metabolic consequences of untreated endometriosis, we must examine the specific pathways that are altered. The chronic inflammation and hormonal imbalances are not abstract concepts; they produce measurable changes in your body’s biochemistry. The systemic release of inflammatory cytokines directly impacts how your liver, fat cells, and muscles function, pushing your metabolism toward a state of inefficiency and distress.

This creates a feedback loop where inflammation drives metabolic dysfunction, and that dysfunction, in turn, can worsen the inflammatory state.

A central feature of this metabolic shift is the development of insulin resistance. Insulin acts like a key, unlocking cells to allow glucose to enter and be used for energy. In a state of chronic inflammation, the “locks” on the cells become less sensitive to the key.

Your pancreas responds by producing more insulin to overcome this resistance, leading to high levels of insulin in the blood (hyperinsulinemia). This compensatory mechanism can work for a while, but it places significant strain on your metabolic system and is a direct precursor to metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

Comparing Metabolic Health Markers

The table below illustrates some common differences in metabolic markers that may be observed in individuals with long-standing endometriosis compared to those without the condition. These changes are a direct reflection of the underlying systemic inflammation and hormonal disruption.

| Metabolic Marker | Typical Profile in Endometriosis | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting Insulin |

Often elevated |

Indicates insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. |

| Fasting Glucose |

May be normal or slightly elevated |

The body is initially able to compensate to keep blood sugar stable, but the system is under stress. |

| Triglycerides |

Often elevated |

A common feature of dyslipidemia, linked to insulin resistance and increased cardiovascular risk. |

| HDL Cholesterol |

Often decreased |

Lower levels of “good” cholesterol are associated with a higher risk of heart disease. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) |

Often elevated |

A direct marker of systemic inflammation. |

The Gut-Metabolism Connection

An emerging area of critical importance is the connection between endometriosis, the gut microbiome, and metabolic health. The composition of your gut bacteria can influence systemic inflammation and estrogen metabolism. An imbalanced microbiome, or dysbiosis, can contribute to a “leaky gut,” allowing inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream and add to the body’s total inflammatory load.

Furthermore, certain gut bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which can reactivate estrogen that was meant to be excreted, contributing to estrogen excess and worsening the hormonal imbalance that fuels endometriosis.

Insulin resistance is a key metabolic consequence, where the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals due to chronic inflammation.

Lifestyle Interventions for Metabolic Support

Addressing the metabolic implications of endometriosis involves a targeted approach to reduce inflammation and support hormonal balance. The following strategies are foundational:

- Anti-Inflammatory Diet ∞ This involves prioritizing whole foods rich in phytonutrients and fiber, such as leafy greens, colorful vegetables, berries, and healthy fats from sources like avocados and olive oil. It also means minimizing pro-inflammatory foods like processed sugars, refined carbohydrates, and industrial seed oils.

- Regular Physical Activity ∞ Consistent movement, particularly a combination of strength training and cardiovascular exercise, improves insulin sensitivity and helps reduce systemic inflammation. Exercise helps muscle cells take up glucose from the blood, lessening the burden on the pancreas.

- Stress Management ∞ Chronic stress elevates cortisol, a hormone that can disrupt blood sugar regulation and contribute to inflammation. Practices like meditation, deep breathing, and adequate sleep are essential for managing the body’s stress response.

- Gut Health Optimization ∞ Supporting the gut microbiome through a diet rich in prebiotic fiber and fermented foods can help reduce systemic inflammation and improve estrogen metabolism.

Academic

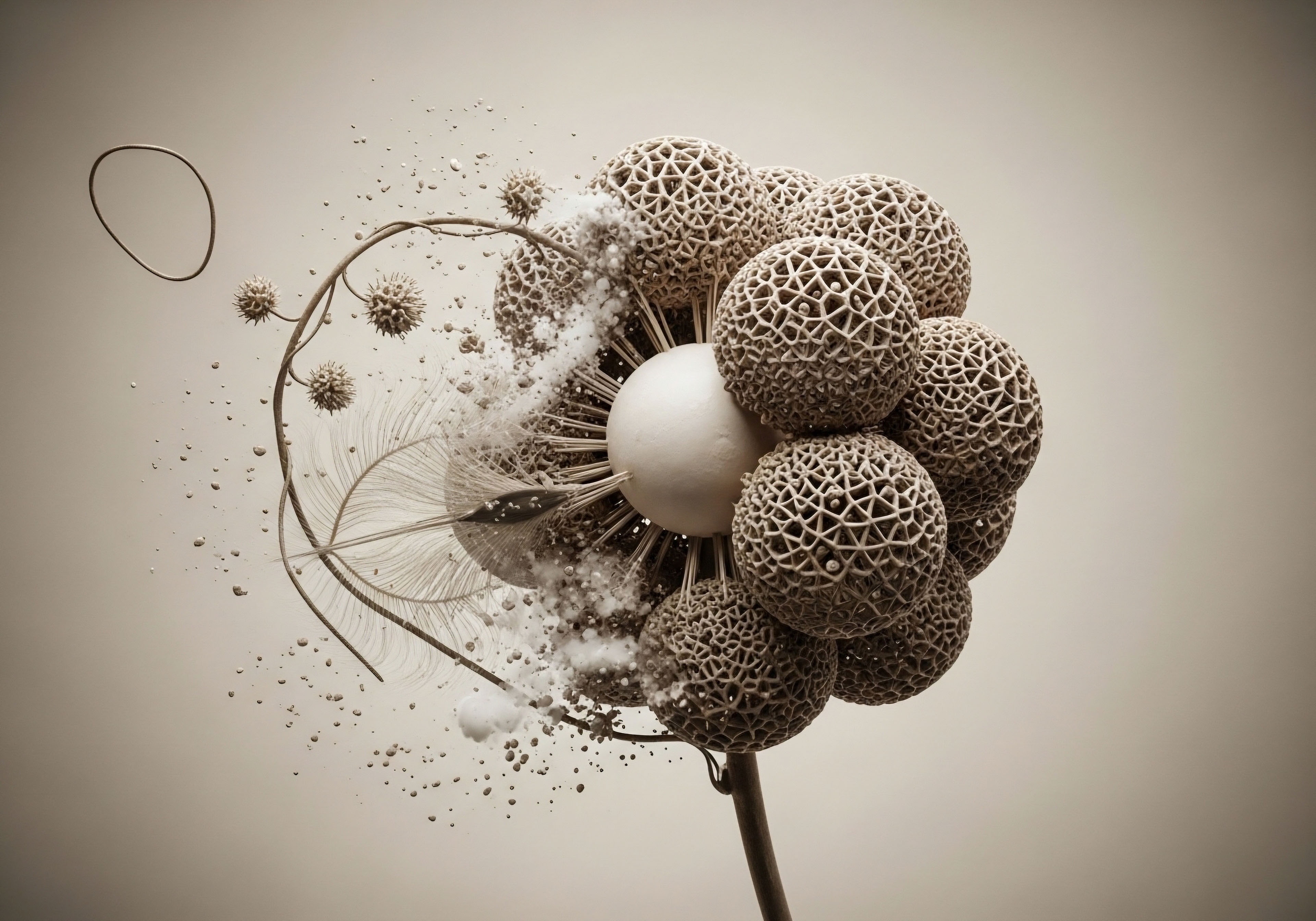

A sophisticated analysis of untreated endometriosis reveals it as a condition of profound systemic dysregulation, extending far beyond its gynecological origins. From a systems-biology perspective, the disease functions as a primary driver of “metainflammation” ∞ a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation triggered by metabolic dysfunction. This process is self-perpetuating. The endometriotic lesions themselves are biochemically active environments that create a hyperestrogenic and pro-inflammatory milieu, which in turn dysregulates systemic metabolic pathways, particularly lipid and glucose homeostasis.

The molecular underpinnings of this disruption are complex. Endometriotic implants possess high levels of aromatase, an enzyme that locally converts androgens into estrogen. This local estrogen production fuels the growth of the lesion while also contributing to the systemic hormonal load.

This process creates a positive feedback loop ∞ estrogen stimulates the production of inflammatory mediators like Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and PGE2, in turn, further stimulates aromatase activity. This localized engine of hormone and cytokine production has systemic consequences, contributing directly to the higher prevalence of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and an increased risk for cardiovascular disease observed in this population.

What Is the Link between Endometriosis and Other Chronic Diseases?

The chronic inflammatory state and immune dysregulation inherent to endometriosis provide a pathophysiological link to an increased risk of other systemic diseases. The persistent elevation of inflammatory markers creates an environment conducive to the development of conditions with an inflammatory basis. Research indicates a consistent association between endometriosis and a higher incidence of certain autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as an elevated risk for cardiovascular events and specific cancers.

The disease acts as a catalyst for metainflammation, a state where metabolic dysfunction and chronic inflammation create a damaging feedback loop.

Inflammatory Mediators in Endometriosis and Metabolic Syndrome

The shared biochemical pathways between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome are evident when examining the specific inflammatory cytokines involved. The following table details key mediators and their roles in both conditions, illustrating the deep biological connection.

| Inflammatory Mediator | Role in Endometriosis | Role in Metabolic Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) |

Promotes lesion survival and proliferation; stimulates angiogenesis (new blood vessel growth). |

Induces insulin resistance in fat and muscle cells; promotes lipid accumulation in the liver. |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) |

Elevated in peritoneal fluid; correlates with disease severity and pain. |

Stimulates the liver to produce C-reactive protein (CRP); linked to insulin resistance. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) |

A systemic marker of inflammation, often elevated in women with endometriosis. |

A key biomarker for cardiovascular risk and a core component of metabolic syndrome diagnostics. |

How Do Treatment Decisions Affect Long Term Health?

The therapeutic management of endometriosis introduces another layer of metabolic consideration. While hormonal treatments that suppress ovarian function can alleviate pain, they may also have metabolic side effects. Surgical interventions, particularly bilateral oophorectomy (removal of both ovaries), induce premature menopause.

This abrupt loss of endogenous estrogen production carries its own significant long-term health risks, including an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic conditions, and earlier mortality, especially when performed before the age of 35. This reality underscores the complexity of managing endometriosis. The goal is to control the disease’s progression while carefully weighing the long-term systemic and metabolic consequences of each potential intervention.

References

- Signos. “Endometriosis and Metabolic Health ∞ Unraveling the Hidden Connection.” 22 May 2025.

- Mayo Clinic. “Endometriosis – Diagnosis and treatment.” 30 Aug. 2024.

- Chou, Yu-Chun, et al. “A Lifelong Impact on Endometriosis ∞ Pathophysiology and Pharmacological Treatment.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 8, 2023, p. 7495.

- Harris, Holly R. et al. “Long-term Health Consequences of Endometriosis ∞ Pathways and Mediation by Treatment.” Current Obstetrics and Gynecology Reports, vol. 9, no. 2, 2020, pp. 29-37.

- Clinton Women’s Healthcare. “What Happens If Endometriosis Is Left Untreated?” 28 Apr. 2025.

Reflection

Your Path to Metabolic Wellness

Understanding the deep connection between endometriosis and your metabolic health is a profound step. The information presented here provides a map of the biological terrain you are navigating. It validates the systemic nature of your symptoms and illuminates the pathways that connect pelvic health to whole-body wellness.

This knowledge is the foundation upon which a truly personalized and effective health strategy is built. Your journey forward involves using this understanding to ask deeper questions, seek comprehensive care, and make informed choices that honor the intricate biology of your own body. You are now equipped to be an active, informed participant in the process of restoring your vitality.