Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A subtle shift in the background rhythm of your body. The energy that once propelled you through demanding days now seems to wane by mid-afternoon.

Sleep, which used to be a restorative reset, now feels unrefreshing, and the reflection in the mirror shows a changing body composition that diet and exercise alone no longer seem to influence. This experience, this quiet accumulation of symptoms, is a deeply personal and often frustrating journey.

It is the lived reality of a biological system undergoing a significant change. At the heart of this transformation is often a key regulator of your body’s vitality and metabolic function ∞ Growth Hormone (GH). Understanding its role is the first step toward reclaiming your biological potential.

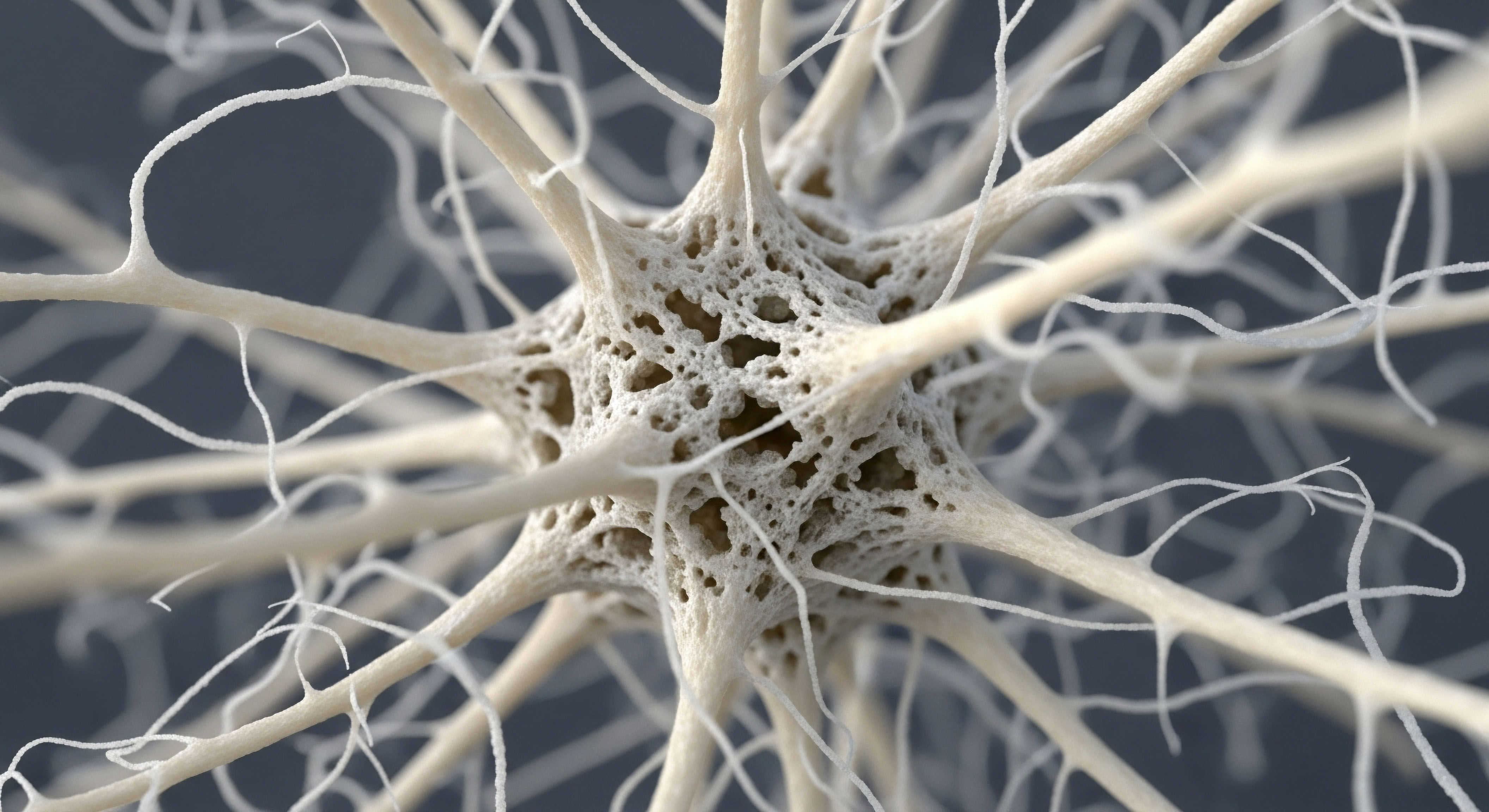

Growth Hormone is the body’s master architect and renovation manager. Produced in the pituitary gland, a small, powerful structure at the base of the brain, GH operates in rhythmic pulses, primarily during deep sleep. Its job is to orchestrate growth during childhood and adolescence.

In adulthood, its role transitions to one of continuous maintenance, repair, and metabolic optimization. Think of it as the conductor of a vast orchestra of cellular processes. It directs your body to burn fat for fuel, to repair and build lean muscle tissue, to maintain bone density, and to support cognitive clarity. When this conductor’s signals become weak or infrequent, the entire metabolic orchestra begins to fall out of sync.

Chronically suppressed Growth Hormone from lifestyle factors initiates a cascade of metabolic dysfunctions, beginning with how your body sources and stores energy.

The suppression of this vital hormone is rarely a sudden event. It is a slow erosion, often driven by the very fabric of modern life. These lifestyle factors are the primary antagonists to your body’s natural GH production. They are the consistent, daily inputs that quietly tell your pituitary gland to dial down its output. Recognizing these factors is fundamental to understanding your own physiology.

The Primary Suppressors of Growth Hormone

The body’s endocrine system is a system of exquisite sensitivity. It responds to every signal it receives, whether from food, stress, or sleep. The chronic presence of certain signals can lead to a state of hormonal suppression, and GH is particularly vulnerable.

- Elevated Insulin Levels ∞ A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars triggers frequent and large releases of insulin. Insulin and Growth Hormone have a complex, inverse relationship. High levels of circulating insulin directly signal the pituitary to halt GH secretion. This is a primary mechanism by which dietary habits directly impact your body’s ability to repair and burn fat.

- Poor Sleep Quality ∞ The most significant pulse of GH is released during the first few hours of deep, slow-wave sleep. Fragmented sleep, insufficient sleep duration, or a disrupted circadian rhythm due to shift work or screen time before bed directly truncates this critical release window. You are, in effect, robbing your body of its most important nightly repair cycle.

- Chronic Stress ∞ Psychological and physiological stress leads to the sustained elevation of cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. Cortisol is catabolic in nature, meaning it breaks down tissues. It also directly inhibits the release of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) from the hypothalamus, effectively cutting off the signal that tells the pituitary to produce GH. This creates a state where the body is biased towards breakdown and fat storage, rather than repair and muscle building.

- Sedentary Behavior ∞ High-intensity exercise is one of the most potent natural stimuli for GH release. A lack of this stimulus means a missed opportunity for hormonal optimization. The physiological demands of intense physical activity signal to the body a need for repair and adaptation, a signal that is powerfully answered by a surge in GH.

What Is the Initial Metabolic Consequence?

The first and most noticeable consequence of chronically suppressed GH is a shift in your body’s fuel preference. With diminished GH signaling, the body’s ability to mobilize and burn stored fat (a process called lipolysis) is significantly impaired. Simultaneously, the body becomes less efficient at utilizing glucose.

This creates a metabolic dilemma ∞ you are less able to burn fat for energy, and your cells become less responsive to the energy provided by carbohydrates. The result is an insidious creep of fat accumulation, particularly in the abdominal region.

This visceral fat is a metabolically active tissue that produces its own inflammatory signals, further disrupting hormonal balance and creating a self-perpetuating cycle of metabolic dysfunction. You experience this as stubborn weight gain, a loss of muscle definition, and a pervasive sense of fatigue, as your body struggles to efficiently power itself.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the fundamentals, we can begin to dissect the specific, cascading failures that occur within your metabolic machinery when Growth Hormone signals are chronically suppressed. This is a journey into the biochemistry of how your body manages energy, builds tissues, and maintains systemic health.

The consequences are far-reaching, extending from your body composition and energy levels to your long-term cardiovascular and cognitive health. Understanding these mechanisms provides the clinical rationale for targeted interventions designed to restore your body’s innate metabolic blueprint.

The state of diminished GH activity, whether from age-related decline (somatopause) or accelerated by lifestyle factors, creates a distinct metabolic phenotype. This profile is characterized by a trio of interconnected issues ∞ altered body composition, dysregulated lipid metabolism, and impaired glucose homeostasis. These are not separate symptoms; they are the downstream results of a single upstream problem ∞ the loss of adequate GH signaling. This loss disrupts the delicate communication between your brain, your fat cells, your muscles, and your liver.

The Remodeling of Body Composition

Growth Hormone is a primary anabolic agent in the adult body, promoting the growth and maintenance of lean tissues. Its chronic suppression fundamentally alters the balance between lean mass and fat mass. This process unfolds through several distinct biological pathways.

Impaired Lipolysis and the Rise of Visceral Fat

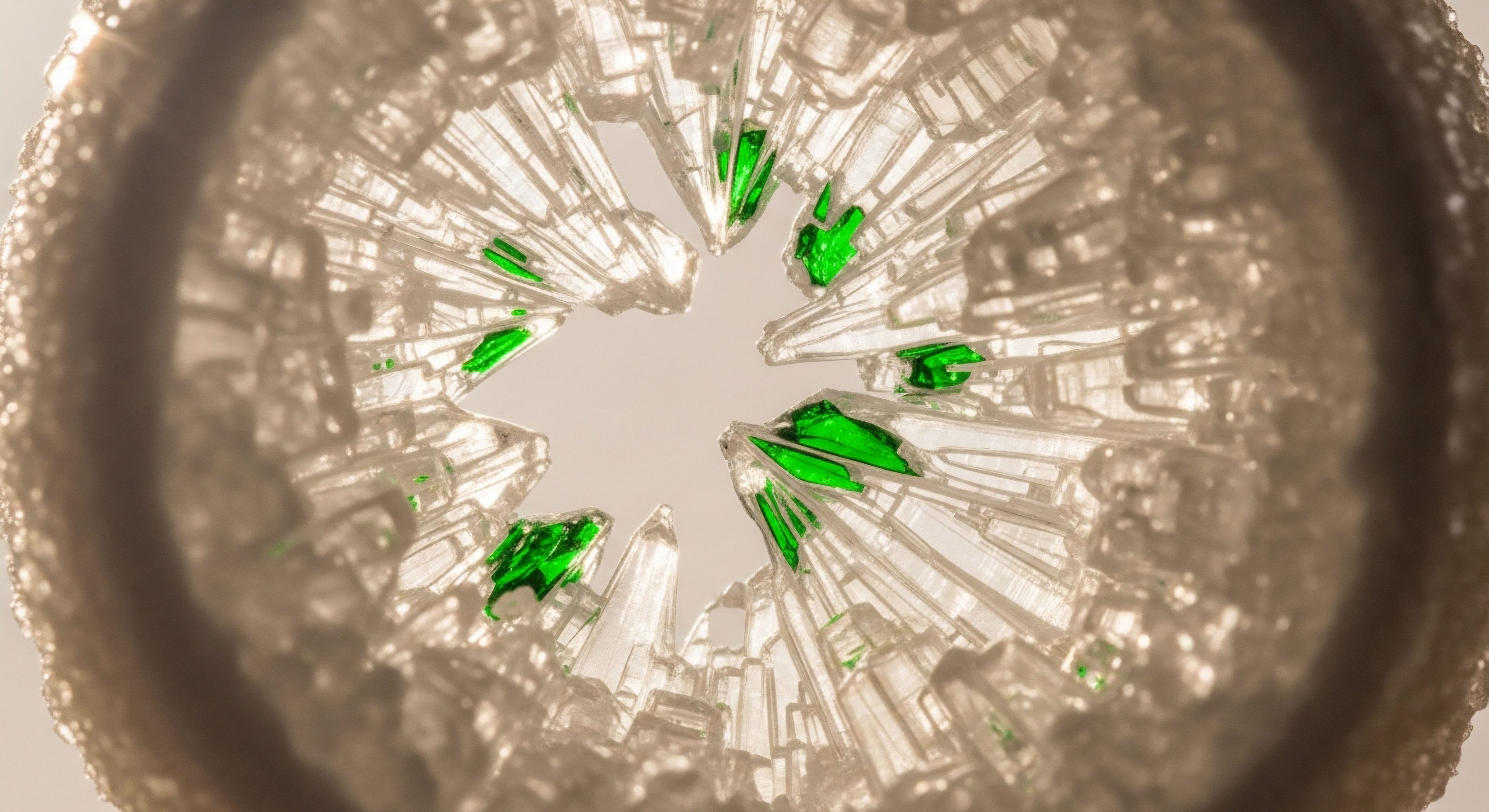

GH directly stimulates lipolysis, the process of breaking down triglycerides stored in adipocytes (fat cells) into free fatty acids that can be used for energy. It does this by activating hormone-sensitive lipase, the key enzyme in this process. When GH levels are low, this brake on fat storage is released. Fat cells become more resistant to releasing their stored energy. The body’s default mode shifts from fat utilization to fat accumulation.

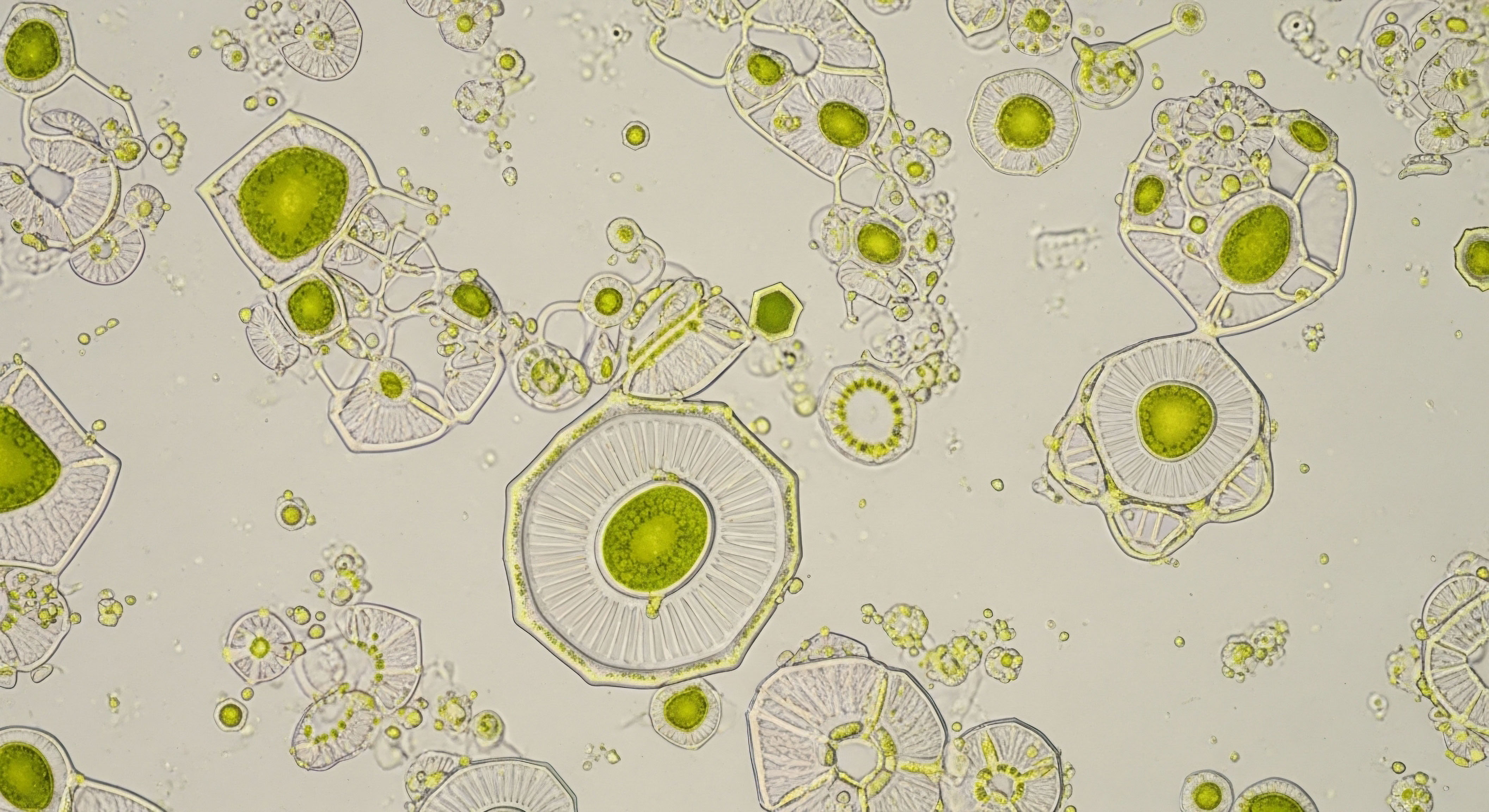

This accumulation is particularly pronounced in the abdominal cavity, leading to an increase in visceral adipose tissue (VAT). VAT is a uniquely pathogenic type of fat. It surrounds the internal organs and functions as an active endocrine organ, secreting a host of inflammatory molecules called adipokines.

These substances, including TNF-alpha and IL-6, promote a state of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation, which is a foundational element of nearly every chronic disease. This inflammatory environment further disrupts insulin signaling and can even exert additional suppressive effects on the HPG (Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal) axis, worsening the overall hormonal imbalance.

Sarcopenia and the Decline in Muscle Mass

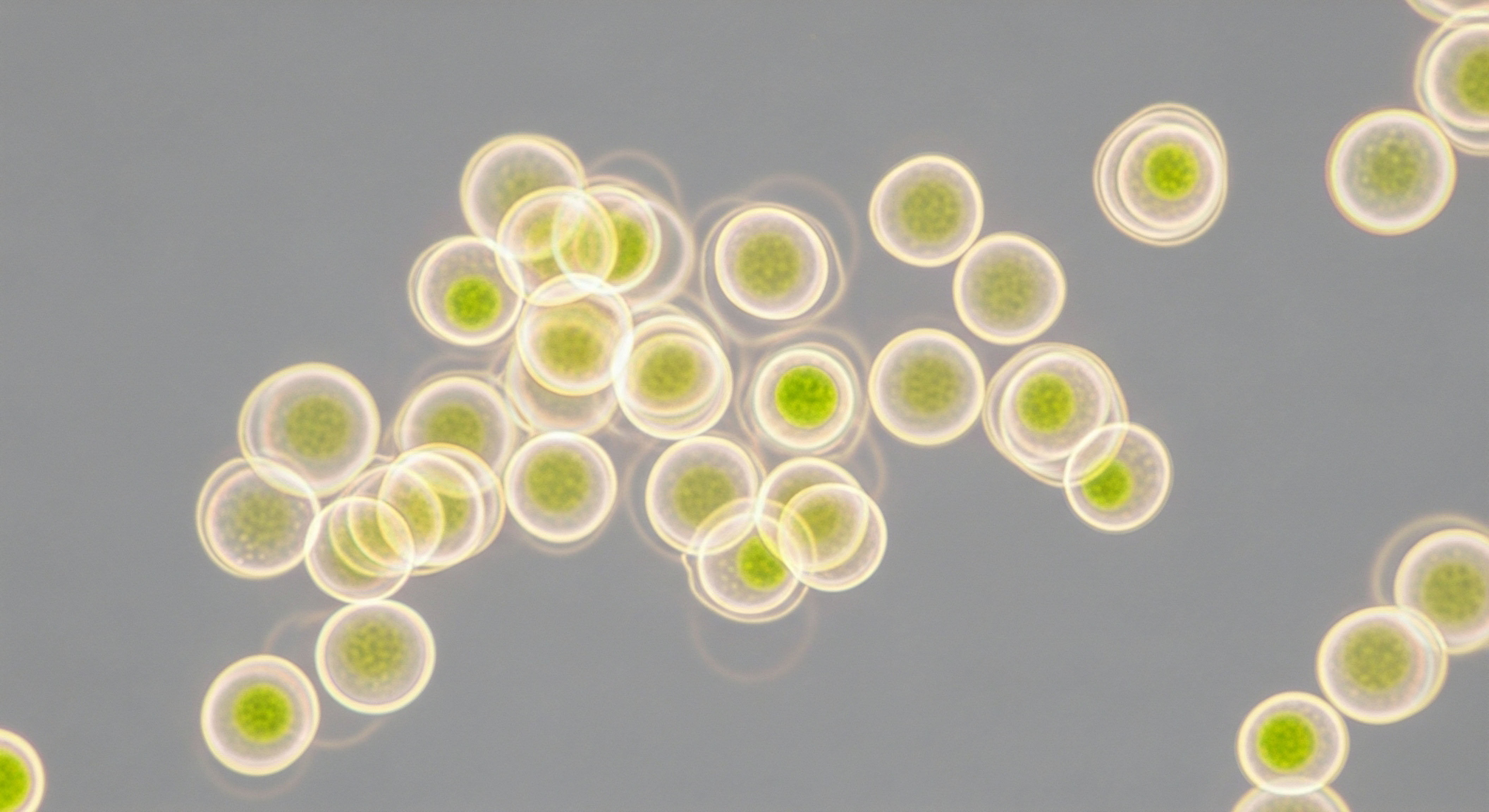

Concurrently with fat accumulation, low GH accelerates the age-related loss of muscle mass and function, a condition known as sarcopenia. GH promotes muscle growth by increasing amino acid uptake and stimulating protein synthesis within muscle cells.

It also stimulates the local production of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) in muscle tissue, which is a potent driver of muscle cell proliferation and differentiation. Without adequate GH signaling, the balance tips from muscle protein synthesis to muscle protein breakdown. This results in a progressive loss of lean body mass, which has profound metabolic consequences.

Muscle is a highly metabolically active tissue, and its loss leads to a significant reduction in your resting metabolic rate. This means you burn fewer calories at rest, making it even easier to gain weight and harder to lose it. This loss of muscle also contributes to physical frailty, reduced strength, and an increased risk of injury.

The shift in body composition due to low Growth Hormone creates a metabolically inefficient state, reducing calorie expenditure at rest and promoting inflammatory fat storage.

The following table illustrates the contrasting metabolic profiles associated with optimal versus suppressed GH levels, providing a clear picture of the systemic shift that occurs.

| Metabolic Parameter | Optimal Growth Hormone Profile | Suppressed Growth Hormone Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Body Composition | Higher lean muscle mass, lower body fat percentage. | Decreased lean muscle mass (sarcopenia), increased total and visceral adiposity. |

| Resting Metabolic Rate | Elevated due to higher muscle mass. | Decreased due to loss of metabolically active muscle tissue. |

| Lipid Profile | Lower LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, higher HDL cholesterol. | Elevated LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, decreased HDL cholesterol (atherogenic dyslipidemia). |

| Insulin Sensitivity | Healthy insulin sensitivity; efficient glucose uptake by cells. | Increased insulin resistance; impaired glucose tolerance. |

| Inflammatory Markers | Low levels of systemic inflammation (e.g. C-reactive protein). | Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-alpha, IL-6) from visceral fat. |

Dyslipidemia the Unseen Cardiovascular Risk

The metabolic consequences of suppressed GH extend deep into your biochemistry, significantly altering your lipid profile in a way that promotes cardiovascular disease. This condition, known as atherogenic dyslipidemia, is a hallmark of the low-GH state.

It is characterized by high levels of LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, often referred to as “bad” cholesterol, and triglycerides, coupled with low levels of HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, the “good” cholesterol. GH plays a direct role in regulating liver function, including the production and clearance of cholesterol.

Reduced GH signaling leads to an overproduction of VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein) by the liver, which is a precursor to LDL, and a reduction in the liver’s ability to clear LDL from the bloodstream. The result is a circulatory environment that is conducive to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques in the arteries, setting the stage for long-term cardiovascular events.

Restoring the Signal Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy

When lifestyle modifications are insufficient to fully restore optimal GH levels, or when a more significant deficit exists, Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy offers a sophisticated clinical strategy. This approach uses specific peptides, which are small protein chains, to stimulate the body’s own production and release of GH from the pituitary gland. This method is designed to mimic the body’s natural pulsatile release of GH, which is a safer and more physiologically balanced approach than direct replacement with synthetic hGH.

These protocols are tailored to individuals, particularly active adults seeking to counteract the metabolic decline associated with suppressed GH and improve body composition, recovery, and sleep quality.

- Sermorelin ∞ This peptide is an analog of GHRH. It works by directly stimulating the pituitary gland to produce and secrete GH. Its action is dependent on the body’s natural feedback loops, making it a very safe and regulated way to increase GH levels.

- Ipamorelin / CJC-1295 ∞ This is a powerful combination therapy. Ipamorelin is a GH secretagogue that stimulates the pituitary with minimal effect on other hormones like cortisol. CJC-1295 is a long-acting GHRH analog that provides a sustained increase in the baseline level of GH, upon which the pulsatile release from Ipamorelin can act. Together, they create a strong and synergistic effect on overall GH levels, promoting fat loss, muscle gain, and improved sleep quality.

- Tesamorelin ∞ This peptide has been specifically studied and approved for the reduction of visceral adipose tissue. It is a highly effective GHRH analog that has demonstrated a powerful ability to target and reduce the most dangerous type of body fat, thereby improving the overall metabolic profile and reducing inflammatory load.

These therapies represent a targeted intervention designed to correct a specific upstream failure in the endocrine system. By restoring the body’s natural GH pulse, they can help to reverse the downstream metabolic consequences, shifting the body back towards a state of efficient fat metabolism, lean tissue maintenance, and systemic health.

Academic

An academic exploration of the long-term metabolic sequelae of chronically suppressed Growth Hormone (GH) necessitates a detailed examination of the molecular and cellular derangements that underpin the gross physiological changes. This perspective moves beyond the observable phenotype of altered body composition and dyslipidemia to the intricate signaling pathways, enzymatic dysfunctions, and organ-specific pathologies that arise from a sustained deficit in GH action.

The central biological system at play is the GH/IGF-1 axis, a complex and tightly regulated network that governs somatic growth and metabolic homeostasis throughout life. Lifestyle-induced suppression of this axis precipitates a cascade of maladaptive responses that culminate in a state of heightened metabolic risk and accelerated cellular aging.

Dysregulation of the Somatotropic Axis

The synthesis and secretion of GH from the somatotroph cells of the anterior pituitary are primarily regulated by a balance of two hypothalamic peptides ∞ Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH), which is stimulatory, and Somatostatin (SST), which is inhibitory. Lifestyle factors such as chronic caloric excess, particularly from refined carbohydrates, lead to hyperinsulinemia.

Insulin at high concentrations can suppress GH secretion both at the hypothalamic level, by decreasing GHRH release, and at the pituitary level, by increasing sensitivity to SST. Similarly, chronic psychosocial stress elevates glucocorticoids, principally cortisol, which inhibits GHRH-mediated GH secretion and can induce hypothalamic resistance to GH feedback, further dysregulating the axis.

GH exerts its effects in two ways ∞ directly, by binding to GH receptors (GHR) on target cells, and indirectly, primarily through the stimulation of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) production in the liver and peripheral tissues. The chronic suppression of GH leads to a state of functional GH deficiency, characterized by low circulating levels of IGF-1. This reduction in both GH and IGF-1 signaling is the primary molecular trigger for the ensuing metabolic chaos.

How Does Cellular Signaling Breakdown?

The binding of GH to its receptor activates the Janus Kinase 2 (JAK2) / Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) pathway. Specifically, STAT5b is the critical mediator of most of GH’s metabolic actions. In a state of suppressed GH, the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT5b are severely attenuated. This has profound consequences for gene expression in target tissues like the liver, adipose tissue, and muscle.

In the liver, STAT5b activation is required for the transcription of the IGF-1 gene. Reduced STAT5b activity directly leads to lower hepatic IGF-1 output. Furthermore, STAT5b regulates the expression of key genes involved in lipid metabolism, including those for LDL receptors. Impaired STAT5b signaling contributes to reduced clearance of LDL cholesterol from the circulation.

In adipose tissue, the lipolytic effects of GH are mediated by the suppression of anti-lipolytic factors and the promotion of lipolytic enzymes. Attenuated GHR signaling allows for unchecked lipid storage and adipocyte hypertrophy.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress

A growing body of evidence indicates that the GH/IGF-1 axis is a critical regulator of mitochondrial function. GH signaling promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and enhances the efficiency of the electron transport chain, thereby increasing cellular energy production (ATP synthesis) while minimizing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

In a low-GH state, mitochondrial density and function decline. This mitochondrial dysfunction has two major metabolic consequences. First, a reduced capacity for fatty acid oxidation means that cells, particularly muscle cells, are less able to use fat for fuel, contributing to lipid accumulation within the muscle (intramyocellular lipids) and exacerbating insulin resistance.

Second, inefficient mitochondrial respiration leads to increased electron leakage and a higher rate of ROS production. This creates a state of chronic oxidative stress, where cellular antioxidant defenses are overwhelmed. Oxidative stress damages cellular proteins, lipids, and DNA, contributing to cellular senescence and the systemic inflammation that characterizes the low-GH state.

The molecular decay from suppressed Growth Hormone signaling impairs mitochondrial energy production and triggers a state of chronic oxidative stress, accelerating cellular aging.

The Pathophysiology of GH-Deficient Dysmetabolism

The integrated effect of these molecular derangements creates a complex clinical picture. The table below provides a granular view of the specific pathophysiological changes and their clinical manifestations that result from chronically suppressed GH.

| System/Tissue | Pathophysiological Mechanism | Clinical/Biochemical Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Adipose Tissue | Decreased activation of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL); increased activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) on adipocytes; adipocyte hypertrophy. | Reduced lipolysis, enhanced triglyceride uptake and storage, preferential accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT). |

| Skeletal Muscle | Reduced amino acid uptake and protein synthesis; decreased local IGF-1 production; impaired mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. | Progressive sarcopenia, reduced resting metabolic rate, accumulation of intramyocellular lipids, contributing to insulin resistance. |

| Liver | Impaired JAK2/STAT5b signaling; reduced expression of LDL receptors; increased de novo lipogenesis. | Decreased hepatic IGF-1 synthesis, hypercholesterolemia (elevated LDL-C), hypertriglyceridemia, potential for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). |

| Cardiovascular System | Atherogenic dyslipidemia; increased systemic inflammation from VAT-derived adipokines; endothelial dysfunction. | Accelerated atherogenesis, increased C-reactive protein (CRP), increased risk for hypertension and cardiovascular events. |

| Pancreatic β-cells | While GH can have contra-insulin effects, chronic deficiency may lead to impaired β-cell compensation in the face of rising insulin resistance. | Initial hyperinsulinemia to compensate for insulin resistance, followed by potential β-cell exhaustion and increased risk for type 2 diabetes. |

What Is the Connection to Insulin Resistance?

The relationship between GH and insulin sensitivity is complex. Acutely, high levels of GH can induce a state of physiological insulin resistance, primarily to spare glucose for the brain during periods of fasting by promoting fat utilization in peripheral tissues. However, the chronic absence of GH leads to a pathological state of insulin resistance through different mechanisms.

The primary driver is the increase in visceral adiposity. The inflammatory cytokines and free fatty acids released from VAT directly interfere with insulin signaling pathways in muscle and liver, leading to impaired glucose uptake and increased hepatic glucose production. The loss of metabolically active muscle tissue also reduces the body’s primary “sink” for glucose disposal.

Therefore, while GH itself can antagonize insulin action, a healthy, pulsatile GH signal is essential for maintaining the lean body mass and low levels of visceral fat required for long-term insulin sensitivity.

In conclusion, the long-term metabolic consequences of chronically suppressed Growth Hormone are a direct result of the disruption of the GH/IGF-1 axis. This disruption initiates a cascade of molecular and cellular events, including impaired intracellular signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and a shift in gene expression that favors a catabolic and pro-inflammatory state.

The clinical manifestations ∞ sarcopenia, visceral obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance ∞ are the macroscopic outcomes of this underlying microscopic decay. Therapeutic interventions, such as Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, are designed to restore the upstream signaling integrity of the somatotropic axis, thereby correcting the downstream metabolic pathology at its source.

References

- Shalet, S. M. et al. “Metabolic effects of stopping growth hormone ∞ body composition and energy expenditure.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 84, no. 1, 1999, pp. 279-84.

- Di Somma, Carolina, et al. “Impact of Long-Term Growth Hormone Replacement Therapy on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Parameters in Adult Growth Hormone Deficiency ∞ Comparison Between Adult and Elderly Patients.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 642337.

- Vijayakumar, Anurag, and Ram K. Menon. “Growth Hormone and Metabolic Homeostasis.” EMJ, 2018, pp. 64-70.

- Giavoli, C. et al. “Impact of Long-Term Growth Hormone Replacement Therapy on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Parameters in Adult Growth Hormone Deficiency ∞ Comparison Between Adult and Elderly Patients.” ResearchGate, 2021.

- Melmed, Shlomo, et al. “Adult Growth Hormone Deficiency- Clinical Management.” Endotext, edited by Kenneth R. Feingold et al. MDText.com, Inc. 2022.

- Johannsson, G. et al. “GH increases extracellular volume by stimulating sodium reabsorption in the distal nephron and preventing pressure natriuresis.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 87, no. 4, 2002, pp. 1743-9.

- Widdowson, W. M. and J. Gibney. “The effect of growth hormone replacement on exercise capacity in patients with GH deficiency ∞ a metaanalysis.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 93, no. 11, 2008, pp. 4413-7.

- Møller, J. et al. “Decreased plasma and extracellular volume in growth hormone deficient adults and the acute and prolonged effects of GH administration ∞ a controlled experimental study.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 44, no. 5, 1996, pp. 533-9.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of your internal biological territory. It details the pathways, the signals, and the systems that govern your metabolic health. You have seen how the subtle, often unseen, choices you make each day ∞ how you eat, how you sleep, how you move, and how you manage stress ∞ are in direct conversation with the deepest parts of your endocrine system.

This knowledge is the foundational tool for change. It transforms the abstract feeling of being unwell into a concrete understanding of physiological processes that can be influenced and optimized.

Consider the trajectory of your own health. Can you identify moments where a shift in lifestyle coincided with a change in your vitality, your body composition, or your mental clarity? The human body is a resilient and adaptive system, but it operates based on the signals it receives.

The journey toward reclaiming your metabolic function begins with a conscious decision to change the quality of those signals. It is an invitation to move from being a passive passenger in your own biology to becoming an active, informed participant. This path is unique to you, and understanding the principles is the first, most powerful step toward navigating it with intention and purpose.