Fundamentals

The feeling often begins as a quiet dissonance within your own body. It might be a persistent fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a subtle shift in your metabolism, or the profound disappointment of seeing another month pass without a desired pregnancy.

Your experience is the primary data point, the lived reality that prompts a search for answers. The intricate processes of reproductive health are profoundly connected to the body’s master metabolic regulator, the thyroid gland. This small, butterfly-shaped gland at the base of your neck orchestrates the energy economy of every cell, and its function is a foundational pillar of overall vitality, including the capacity to create life.

Understanding this connection begins with appreciating the body’s internal communication network. The brain, specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, acts as a central command. The pituitary releases Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH), a chemical messenger that travels through the bloodstream to the thyroid gland, instructing it on how much thyroid hormone to produce.

These hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), then travel to every tissue, setting the pace of cellular activity. This entire circuit, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, is a finely tuned feedback loop designed to maintain metabolic equilibrium.

The Metabolic Setting and Reproduction

When the thyroid produces insufficient hormone, a state known as hypothyroidism, the body’s entire metabolism slows. Cellular processes become sluggish, conserving energy as a primary survival response. Conversely, hyperthyroidism occurs when the thyroid produces an excess of hormone, sending the body into a state of metabolic overdrive, where cellular processes accelerate to an unsustainable pace. Both states represent a significant deviation from the balance required for optimal function.

The reproductive system is exquisitely sensitive to this metabolic setting. From a biological standpoint, reproduction is an energy-intensive process. The body must possess sufficient resources to support not only itself but also the potential for a new life.

When the thyroid signals a state of energy deficit (hypothyroidism) or chaotic energy expenditure (hyperthyroidism), the body intelligently deprioritizes functions that are not immediately essential for survival. Reproductive capacity is one of the first systems to be downregulated in response to this perceived systemic stress. This is a protective mechanism, a biological wisdom that safeguards the body’s core functions when resources are perceived as scarce or mismanaged.

The thyroid gland’s function dictates the body’s systemic energy policy, which in turn governs the priority placed on reproductive processes.

Initial Signs in the Reproductive Sphere

The first manifestations of this downregulation often appear as changes in reproductive health. For women, this can present as irregular menstrual cycles, cycles where ovulation does not occur (anovulation), or changes in menstrual flow. For men, the effects can manifest as a decline in libido or changes in erectile function.

These symptoms are direct consequences of the hormonal crosstalk between the thyroid and the reproductive organs. The ovaries and testes are rich with receptors for thyroid hormones, meaning their function is directly modulated by the signals they receive from the thyroid. An unstable signal leads to unstable function. Acknowledging these early signs is the first step in recognizing that a challenge in reproductive health may have its origins in the body’s broader endocrine and metabolic environment.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond the foundational understanding of the thyroid’s role reveals a more detailed biochemical landscape where thyroid hormones directly orchestrate reproductive physiology. The long-term consequences of untreated thyroid dysfunction are a cascade of disruptions that extend deep into the hormonal signaling required for fertility and healthy pregnancy. The body does not interpret these conditions as a localized problem but as a systemic state of emergency that requires a reallocation of biological resources away from reproduction.

How Does Thyroid Dysfunction Affect Female Reproductive Health?

In women, the regularity and success of the menstrual cycle depend on a precise, rhythmic dialogue between the brain and the ovaries, known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Thyroid hormones are a critical modulator of this dialogue. Untreated hypothyroidism can disrupt this system in several distinct ways, leading to significant long-term challenges.

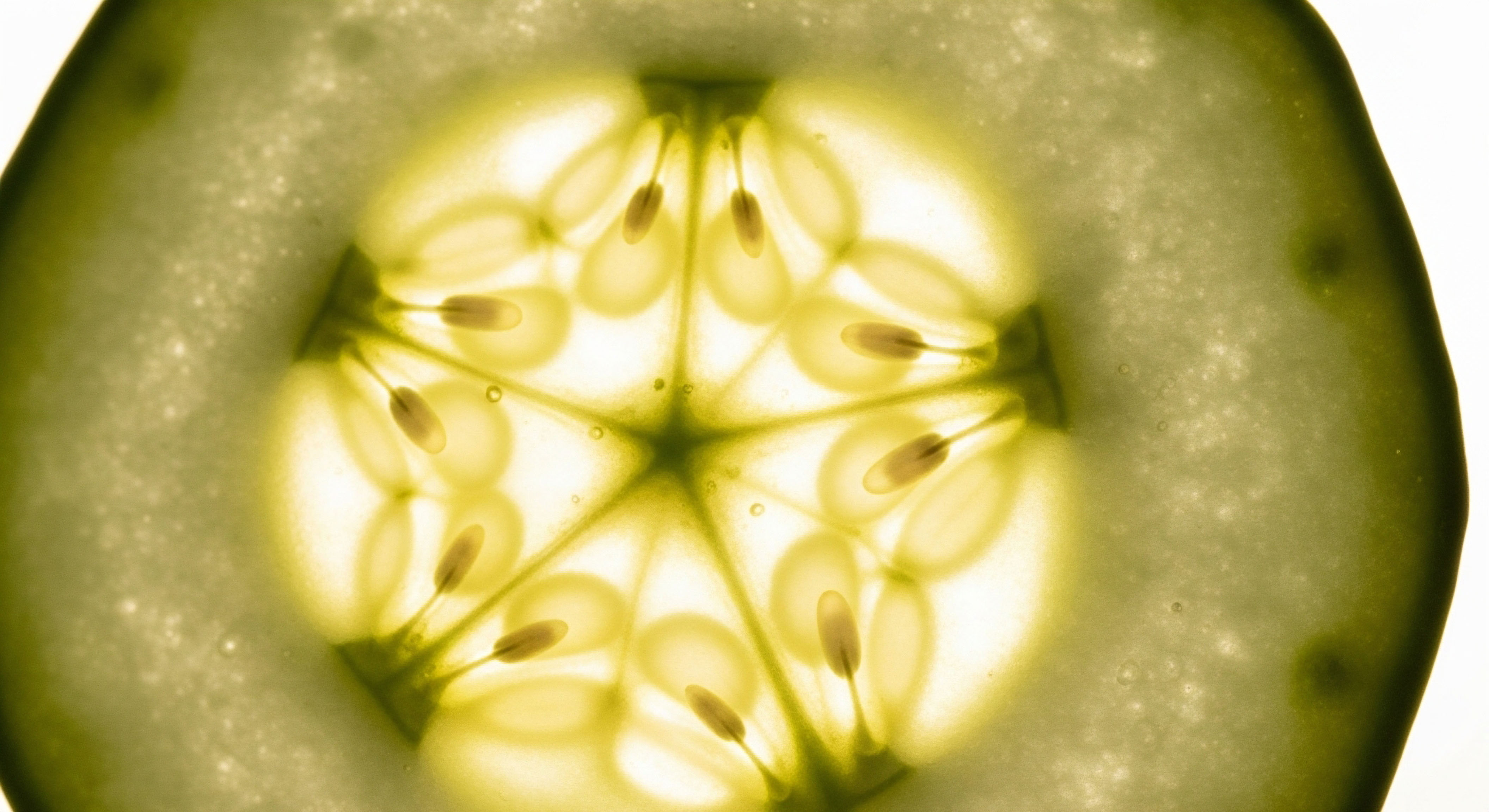

One primary mechanism is the disruption of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion from the hypothalamus. Altered GnRH pulses lead to irregular secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) from the pituitary. This dysregulation directly impairs follicular development in the ovary and can prevent ovulation altogether.

Furthermore, hypothyroidism is often associated with elevated levels of prolactin, a hormone that can directly suppress ovarian function and inhibit ovulation. The cumulative effect is a reproductive system that is functionally suppressed. Hyperthyroidism similarly disrupts the HPG axis, often leading to irregular cycles and menstrual abnormalities.

For women who do conceive, untreated thyroid conditions pose substantial risks. The delicate processes of implantation, placental development, and fetal growth are all dependent on a stable maternal metabolic environment. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism are linked to a greater incidence of miscarriage, pre-term delivery, and other pregnancy complications like preeclampsia. The fetus relies entirely on the mother for thyroid hormone in the first trimester, a period critical for neurological development.

Untreated thyroid dysfunction fundamentally destabilizes the hormonal architecture required for ovulation, conception, and successful gestation.

What Is the Impact on Male Reproductive Potential?

In men, reproductive health is centered on the continuous production of sperm (spermatogenesis) and the synthesis of testosterone, processes governed by the testes. Thyroid hormones are essential for the normal function of both the Sertoli cells, which support sperm development, and the Leydig cells, which produce testosterone.

Hyperthyroidism, for instance, often causes a significant increase in Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) levels. While this may elevate total testosterone in the blood, it reduces the amount of biologically active free testosterone available to the tissues. This can lead to symptoms like reduced libido and contributes to erectile dysfunction. The direct effects on the testes are also pronounced, with hyperthyroidism being linked to impaired sperm motility and a reduction in overall sperm count.

Hypothyroidism also exerts a profound effect. It is associated with abnormalities in sperm morphology (the shape and structure of sperm), which can impair their ability to fertilize an egg. Delayed ejaculation and low libido are also common clinical findings, stemming from both the direct hormonal impact and the systemic effects of a slowed metabolism, such as fatigue. The long-term consequence of either untreated condition is a steady decline in male fertility potential.

| Feature | Hypothyroidism (Underactive) | Hyperthyroidism (Overactive) |

|---|---|---|

| Female Menstrual Cycle | Irregular, heavy, or absent periods (amenorrhea); anovulatory cycles. | Irregular, light, or infrequent periods (oligomenorrhea). |

| Female Fertility | Reduced ability to conceive due to anovulation and luteal phase defects. | Difficulty conceiving due to cycle disruption and hormonal imbalance. |

| Pregnancy Outcomes | Increased risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, preeclampsia, and impaired fetal neurodevelopment. | Elevated risk of miscarriage and premature birth. |

| Male Libido & Function | Decreased libido, potential for delayed ejaculation. | Erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation, and decreased libido are common. |

| Sperm Parameters | Associated with poor sperm morphology (abnormal shape). | Reduced sperm count, decreased motility, and abnormal morphology. |

| Core Hormonal Mechanism | Disrupted GnRH pulses, potential for elevated prolactin, slowing of metabolic processes. | Increased SHBG leading to lower free testosterone, metabolic overdrive, disrupted GnRH pulses. |

The Role of Thyroid Autoimmunity

A significant portion of thyroid dysfunction stems from autoimmunity, where the immune system mistakenly attacks the thyroid gland. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the leading cause of hypothyroidism, and Graves’ disease is the primary cause of hyperthyroidism.

In the context of reproductive health, the presence of thyroid antibodies, such as thyroperoxidase antibodies (TPOAb), represents an independent risk factor, even when thyroid hormone levels are within the normal range (euthyroid). The presence of these antibodies is associated with an increased risk of infertility and pregnancy loss. This suggests that the underlying immune dysregulation itself, not just the resulting hormonal imbalance, may play a direct role in reproductive failure, possibly by affecting ovarian function or implantation.

Academic

A granular examination of the thyroid-gonadal axis reveals a sophisticated network of molecular interactions that dictate reproductive capacity. The long-term sequelae of untreated thyroid dysfunction are not merely symptomatic; they are the macroscopic manifestation of profound disruptions at the cellular and genomic levels.

The primary active thyroid hormone, triiodothyronine (T3), functions as a potent transcription factor, directly regulating the genetic machinery within the reproductive organs. Its absence or excess creates a state of cellular mismanagement that compromises gametogenesis, steroidogenesis, and the viability of a pregnancy.

Genomic Action of Thyroid Hormones in Gonadal Cells

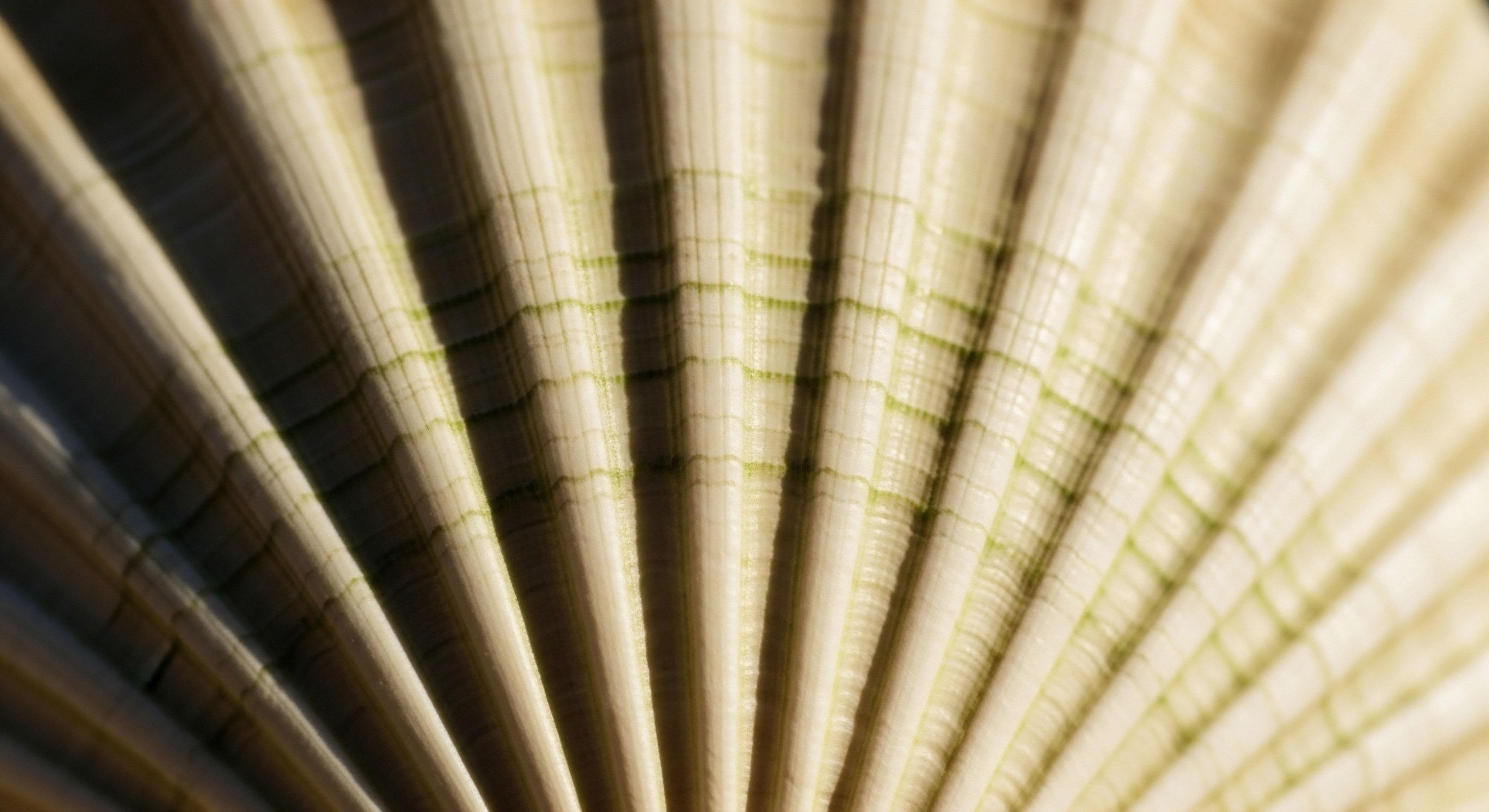

The primary mechanism of T3 action is genomic. T3 enters target cells, such as testicular Leydig and Sertoli cells or ovarian granulosa cells, and binds to specific nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), principally TRα and TRβ. This binding event transforms the receptor into an active transcription factor.

The T3-TR complex then binds to specific DNA sequences known as Thyroid Hormone Response Elements (TREs) located in the promoter regions of target genes. This binding initiates the transcription of genes essential for reproductive function.

In testicular Leydig cells, one of the most critical genes regulated by T3 is the one encoding the Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory (StAR) protein. The StAR protein facilitates the transport of cholesterol into the mitochondria, which is the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of all steroid hormones, including testosterone.

Studies have demonstrated that T3 directly stimulates StAR gene expression. Therefore, in hypothyroidism, reduced T3 levels lead to diminished StAR expression, resulting in impaired testosterone production. This provides a direct molecular link between an underactive thyroid and male hypogonadism. This genomic regulation extends to other enzymes in the steroidogenic pathway, creating a multi-layered control system.

- Sertoli Cells ∞ These cells, essential for nurturing developing sperm, are highly responsive to T3. Thyroid hormone is critical for their maturation and proliferation during development, ultimately determining adult testis size and sperm production capacity.

- Leydig Cells ∞ As discussed, T3 is a key regulator of steroidogenesis in these cells. It modulates the expression of StAR and other enzymes required for testosterone synthesis, directly linking thyroid status to androgen levels.

- Granulosa Cells ∞ In the ovary, these cells surround and support the developing oocyte. T3 action within granulosa cells is vital for follicular growth and responsiveness to gonadotropins like FSH and LH. Thyroid dysfunction can impair this responsiveness, leading to failed ovulation.

The Intricacies of Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH), biochemically defined by an elevated TSH with normal free T4 levels, represents a state of compensated thyroid failure. Its impact on reproductive health is an area of intense clinical investigation. While overt hypothyroidism is clearly detrimental, the effects of SCH are more subtle, yet significant.

Meta-analyses of cohort studies have shown that SCH is associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including pregnancy loss and preterm birth. This suggests that even a mild degree of thyroid insufficiency, reflected only by a rising TSH, is enough to destabilize the maternal-fetal environment.

The debate continues regarding preconception treatment of SCH to improve fertility outcomes. Some randomized controlled trials have not shown a clear benefit in improving live birth rates, particularly when the TSH is only mildly elevated (e.g. 2.5-4.0 mU/L). However, the evidence is stronger for a detrimental effect on pregnancy once it is established.

This distinction is critical and highlights the evolving understanding of how different degrees of thyroid stress impact different phases of the reproductive process. The presence of thyroid autoimmunity alongside SCH appears to confer an even higher risk, pointing to a “two-hit” model where both immune dysregulation and mild hormonal insufficiency contribute to poor outcomes.

At the molecular level, thyroid hormones are not merely permissive but actively instructional, directing the genetic programs that underpin steroid production and gamete viability.

Bidirectional Crosstalk and Systemic Integration

The relationship between the thyroid and the gonads is not unidirectional. Sex hormones, particularly estrogen, influence thyroid function. Estrogen increases the hepatic synthesis of thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), the primary transport protein for thyroid hormones. Higher TBG levels reduce the amount of free, active thyroid hormone, which in turn stimulates the pituitary to release more TSH to compensate.

This is why thyroid hormone requirements increase significantly during pregnancy, a state of high estrogen. In a woman with limited thyroid reserve, such as in early Hashimoto’s disease, this increased demand cannot be met, leading to overt hypothyroidism during gestation.

This bidirectional communication underscores the integrated nature of the endocrine system. A dysfunction in one axis reverberates through the others. Untreated thyroid disease, therefore, is a state of systemic metabolic dysregulation that cannot be isolated from its profound and lasting implications for reproductive health. The clinical picture of infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss is often the final, downstream consequence of a cascade that begins with a failure of cellular energy management orchestrated by the thyroid gland.

| Mediator | Type | Function in Reproductive Tissues | Impact of Dysfunction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid Hormone Receptor α (TRα) | Nuclear Receptor | Mediates T3 signaling in Sertoli and Leydig cells, crucial for testicular development and steroidogenesis. | Altered expression or function impairs male gonadal development and function. |

| Thyroid Hormone Receptor β (TRβ) | Nuclear Receptor | Also mediates T3 signaling in gonadal cells, contributing to the regulation of gene expression. | Contributes to the overall picture of thyroid-mediated reproductive disruption. |

| StAR Protein | Transport Protein | Rate-limiting protein in steroid hormone synthesis; transports cholesterol into mitochondria in Leydig and granulosa cells. Its expression is stimulated by T3. | Reduced T3 in hypothyroidism leads to lower StAR levels and impaired testosterone/progesterone synthesis. |

| Deiodinases (Types 1, 2, 3) | Enzymes | Locally convert inactive T4 to active T3 (D1, D2) or inactivate T3 (D3) within gonadal tissues, allowing for fine-tuned local control of thyroid action. | Dysregulation of local deiodinase activity can create a state of cellular hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism even with normal serum hormone levels. |

| Thyroperoxidase Antibodies (TPOAb) | Autoantibody | Indicates autoimmune thyroid disease. Associated with increased risk of infertility and miscarriage, independent of hormone levels. | Their presence suggests an underlying inflammatory state that may directly harm reproductive processes. |

References

- Krassas, G. E. Poppe, K. & Glinoer, D. (2010). Thyroid function and human reproductive health. Endocrine Reviews, 31(5), 702 ∞ 755.

- Dittrich, R. Kajaia, N. & Cupisti, S. (2021). Thyroid autoimmunity and its negative impact on female fertility and maternal pregnancy outcomes. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12, 1049665.

- Macerola, B. et al. (2018). Thyroid Hormone Deiodination and Action in the Gonads. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research, 1, 49-55.

- Maraka, S. Ospina, N. M. S. O’Keeffe, D. T. & Montori, V. M. (2016). Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid, 26(4), 580-590.

- Manna, P. R. Tena-Sempere, M. & Huhtaniemi, I. T. (1999). Molecular mechanisms of thyroid hormone-stimulated steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig tumor cells. Involvement of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274(9), 5909 ∞ 5918.

- Wajner, S. M. & Maia, A. L. (2012). New insights into thyroid hormone action. Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, 84(1), 23-34.

- Garelli, S. et al. (2013). High prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 169(2), 254-257.

- La Vignera, S. et al. (2015). Thyroid function and semen quality. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 38(3), 327-333.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map of the biological territory, connecting the subtle signals of your body to the profound mechanics of cellular function. This knowledge is a powerful tool, transforming abstract symptoms into a coherent physiological story. It shifts the perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active inquiry.

Your personal health narrative is the most important text in this process. The data from clinical science provides the language, but you provide the context. What does this integrated understanding of metabolic and reproductive health mean for your path forward?

How does knowing the ‘why’ behind the ‘what’ change the questions you ask and the partnership you form with your health providers? The journey toward reclaiming biological harmony begins not with a protocol, but with this deeper, more compassionate understanding of the intricate, intelligent system you inhabit.