Fundamentals

That persistent feeling of being simultaneously exhausted and on high alert is a tangible biological signal. Your experience of fatigue, the difficulty concentrating, the sense that your body is working against you ∞ these are direct manifestations of a sophisticated internal communication system operating under duress.

This system, evolved for short-term survival, is now caught in a relentless cycle driven by the pressures of modern life. Understanding this mechanism is the first step toward reclaiming your body’s inherent capacity for vitality. The conversation about your health begins with appreciating how your body interprets and responds to its environment, translating external pressures into internal biochemical realities.

The core of this response lies within a neuroendocrine circuit known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of this as your body’s crisis management team. When your brain perceives a threat ∞ be it a physical danger, an emotional challenge, or a physiological stressor like poor sleep or infection ∞ the hypothalamus acts as the command center. It releases a signaling molecule, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which is a direct order to the pituitary gland.

The Body’s Internal Command Chain

The pituitary, the master gland, receives this message and dispatches its own messenger, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), into the bloodstream. ACTH travels to the adrenal glands, which are small, powerful glands sitting atop your kidneys. This is where the final directive is executed.

In response to ACTH, the adrenal cortex produces and releases cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. In an acute situation, cortisol is a powerful and necessary ally. Its main job is to mobilize energy to deal with the immediate threat. It does this by rapidly increasing the amount of glucose (sugar) available in your bloodstream, ensuring your brain, muscles, and vital systems have the fuel needed for a fight-or-flight response.

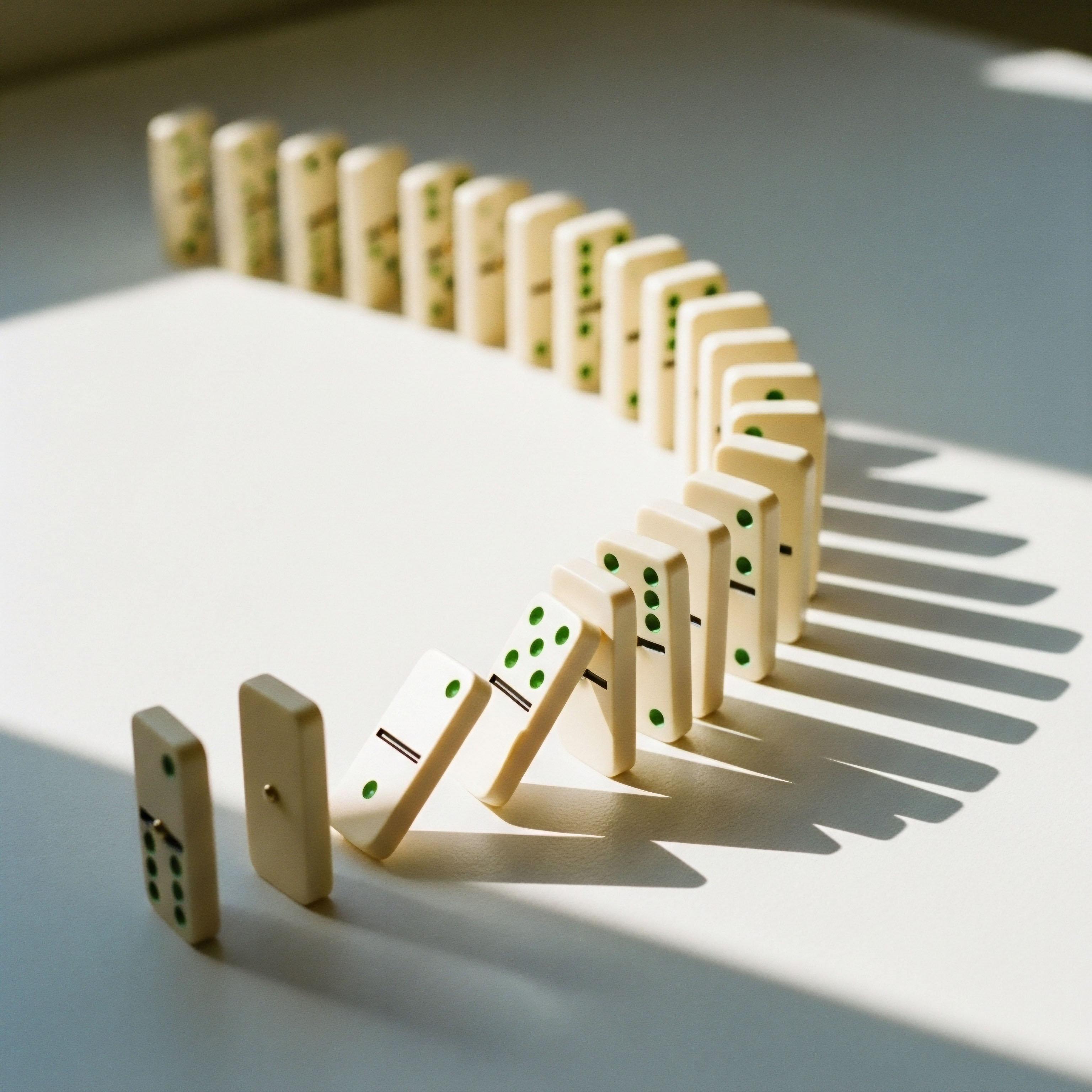

This system is designed with a self-regulating feedback loop. Once cortisol levels are high enough, the hormone itself signals back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to stop producing CRH and ACTH. This is the “all clear” signal, the biochemical instruction to stand down. This elegant loop ensures that the powerful effects of cortisol are temporary and that the body can return to its normal state of equilibrium, or homeostasis, once the threat has passed.

The body’s stress response is an intricate and potent system designed for acute survival, not for chronic, unrelenting activation.

When the off Switch Breaks

Unmanaged, long-term stress fundamentally disrupts this system. The constant perception of threat means the hypothalamus never receives the “all clear” signal. It continues to send out CRH, which keeps the entire cascade active. The adrenal glands are commanded to produce cortisol day after day, leading to chronically elevated levels in the bloodstream.

The negative feedback loop, the critical off-switch, becomes progressively less effective. Your body is stuck in a state of high alert, and the very hormone that was meant to help you survive a short-term crisis now begins to systematically degrade your metabolic health.

This state of cumulative biological wear and tear is known as allostatic load. One of its first and most significant casualties is your metabolic function. Chronically high cortisol continuously instructs the liver to release glucose while simultaneously making your body’s cells less responsive to insulin, the hormone responsible for escorting glucose out of the blood and into cells for energy.

This creates a scenario where your blood is flooded with sugar that your cells cannot effectively use. This is the foundational step on the path toward profound metabolic dysfunction, a journey that begins with the simple, sustained activation of your stress response.

- Energy Mobilization ∞ Cortisol triggers the liver to convert its stored glycogen into glucose and release it into the bloodstream. It also facilitates the breakdown of proteins and fats into glucose.

- Heightened Alertness ∞ It increases focus and can improve eyesight and memory in the short term, preparing you to react quickly to a threat.

- Blood Pressure Increase ∞ The hormone constricts blood vessels to direct more blood to the muscles and essential organs needed for immediate action.

- System De-prioritization ∞ Functions non-essential for immediate survival, such as digestion, reproduction, and aspects of the immune response, are temporarily suppressed to conserve energy.

Intermediate

As the stress response transitions from an acute, protective mechanism to a chronic state, the HPA axis itself begins to malfunction in predictable patterns. The initial phase is characterized by hypercortisolism, a state of consistently high cortisol output. The adrenal glands are working overtime to meet the perceived demand.

Over a prolonged period, this can transition into a more complex state of dysregulation. Some individuals may develop a blunted cortisol awakening response (CAR), where the natural morning surge of cortisol is diminished, leading to fatigue and difficulty starting the day. In later stages, the system may progress to hypocortisolism, where the adrenal glands’ capacity to produce cortisol becomes exhausted, resulting in chronically low levels and a state often described as “burnout.”

The Vicious Cycle of Insulin and Cortisol

The metabolic consequences of sustained hypercortisolism are centered on its relationship with insulin. This interaction creates a destructive feedback loop that accelerates metabolic decline. Cortisol’s primary directive is to ensure high energy availability. It achieves this by promoting gluconeogenesis in the liver, a process where the liver creates new glucose from amino acids and glycerol.

Simultaneously, cortisol induces a state of insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, specifically muscle and fat cells. It effectively tells these cells to ignore insulin’s signal to absorb glucose from the blood. This ensures that the brain has priority access to the circulating fuel.

The pancreas, sensing high blood glucose, responds by producing more insulin in an attempt to overcome this resistance. The result is a state of hyperinsulinemia, where the blood contains high levels of both glucose and insulin. This combination is a primary driver of metabolic disease.

High insulin levels promote fat storage, particularly in the abdominal region. This visceral adipose tissue is not inert; it is a metabolically active organ that secretes its own inflammatory signals, further worsening insulin resistance throughout the body.

Sustained cortisol elevation forces the body into a state of perpetual energy surplus in the bloodstream, which it then stores as inflammatory visceral fat.

This cycle is self-perpetuating. The more visceral fat you accumulate, the more inflammatory signals are produced, and the more insulin resistant your cells become. The pancreas must then work even harder, and the cycle intensifies, paving the way for conditions like metabolic syndrome, pre-diabetes, and eventually type 2 diabetes.

| Metabolic Marker | Acute Cortisol Response (Short-Term Stress) | Chronic Cortisol Elevation (Unmanaged Stress) |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Glucose |

Rapid, temporary increase to provide immediate energy. |

Sustained high levels (hyperglycemia) as the liver continuously produces glucose. |

| Insulin Sensitivity |

Temporarily reduced in muscle/fat to prioritize glucose for the brain. |

Persistently low (insulin resistance); cells become numb to insulin’s signal. |

| Insulin Production |

Initially suppressed, then rises to restore normal glucose levels post-stressor. |

Chronically high (hyperinsulinemia) as the pancreas overworks to control blood glucose. |

| Adipose Tissue (Fat) |

Lipolysis (fat breakdown) is stimulated to provide fuel. |

Lipogenesis (fat creation) is promoted, especially visceral fat accumulation around the organs. |

| Liver Function |

Stimulates glycogenolysis (breakdown of stored glucose). |

Promotes constant gluconeogenesis (creation of new glucose) and can lead to fatty liver disease. |

How Does Stress Affect Sex Hormones?

The HPA axis does not operate in isolation. Its chronic activation has significant downstream effects on other critical endocrine systems, most notably the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which governs reproductive function and sex hormone production. The body, when under perceived threat, prioritizes survival over procreation.

The biochemical precursor molecule for both cortisol and sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen is pregnenolone. During chronic stress, the body shunts pregnenolone down the pathway toward cortisol production at the expense of producing sex hormones. This phenomenon is often referred to as “pregnenolone steal.”

For men, sustained HPA activation can suppress the signaling from the pituitary that stimulates testosterone production in the testes. This can lead to symptoms of low testosterone, including fatigue, decreased libido, loss of muscle mass, and cognitive difficulties, a clinical picture that mirrors andropause. For women, the disruption is equally profound.

The delicate balance between estrogen and progesterone can be thrown into disarray, leading to irregular menstrual cycles, worsening of premenstrual symptoms, and a more challenging transition through perimenopause and menopause. Understanding this crosstalk is essential, as addressing metabolic health requires a comprehensive view of the entire endocrine network.

Academic

The progression from chronic stress to metabolic syndrome involves a sophisticated molecular adaptation that ultimately becomes maladaptive. At the heart of this process is the phenomenon of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) resistance. Glucocorticoid receptors are proteins within virtually every cell of the body that bind to cortisol and translate its message into a cellular action.

Under normal conditions, the binding of cortisol to its receptor in the brain provides the negative feedback signal that inhibits the HPA axis. However, prolonged exposure to high levels of cortisol initiates a protective downregulation of these receptors. The cells, in an attempt to shield themselves from the incessant hormonal stimulation, reduce the number of available GRs or alter their binding affinity.

The Paradox of Receptor Insensitivity

This cellular self-preservation creates a systemic paradox. As GRs in the hypothalamus and pituitary become resistant, they no longer effectively “hear” cortisol’s message to shut down. The brain perceives a state of cortisol deficiency, even though circulating levels are high.

In response, the HPA axis continues its output of CRH and ACTH, driving the adrenal glands to produce even more cortisol. This results in a state of functional hypercortisolism, where extremely high levels of the hormone are required to elicit a biological effect, and the crucial negative feedback mechanism is fundamentally broken.

This GR resistance is not uniform across all tissues. Receptors in the brain’s limbic system (involved in emotion and memory) may become highly resistant, while receptors in other tissues, such as adipose tissue, may remain more sensitive. This differential sensitivity explains why chronic stress can lead to both cognitive dysfunction and mood disturbances (as the brain’s emotional centers are dysregulated) and pronounced metabolic effects like visceral obesity (as fat cells continue to respond to cortisol’s lipogenic signals).

Glucocorticoid receptor resistance breaks the body’s primary endocrine feedback loop, creating a runaway train of hormonal signaling that drives both neurological and metabolic disease.

Systemic Consequences of Cellular Dysfunction

The development of GR resistance has profound implications for systemic inflammation. One of cortisol’s primary roles is to modulate the immune response. It acts as a powerful anti-inflammatory agent by binding to GRs on immune cells and suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

When these immune cells develop GR resistance, cortisol’s ability to restrain inflammation is lost. This allows the immune system to shift into a chronic pro-inflammatory state, which is itself a major driver of insulin resistance. Inflammatory cytokines directly interfere with insulin signaling pathways within cells, creating a vicious cycle where HPA axis dysregulation promotes inflammation, and that inflammation, in turn, exacerbates the metabolic dysfunction.

At the neurobiological level, GR resistance in the hippocampus impairs neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, contributing to the memory deficits and “brain fog” commonly reported in individuals with chronic stress and burnout. Concurrently, altered GR function in the amygdala can potentiate feelings of anxiety and fear, locking the individual into the very psychological state that perpetuates the HPA axis activation. The system becomes a closed loop, where the physiological consequences of stress reinforce the psychological experience of it.

| Tissue/System | Function Under Normal GR Sensitivity | Pathophysiology Under GR Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus/Pituitary |

Cortisol binds to GRs, initiating negative feedback to suppress CRH and ACTH production. |

Feedback signal is lost; HPA axis remains chronically activated, leading to hypercortisolism. |

| Hippocampus |

Regulates memory, learning, and contributes to HPA axis inhibition. |

Impaired neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity deficits, and memory problems. Contributes to mood disorders. |

| Adipose Tissue |

Modulates fat storage and distribution. |

Preferential accumulation of visceral fat, as these cells may remain sensitive to high cortisol levels. |

| Immune Cells |

Cortisol suppresses the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, controlling inflammation. |

Loss of anti-inflammatory effect, leading to a chronic, low-grade systemic inflammatory state. |

| Liver |

Cortisol stimulates gluconeogenesis in a controlled manner. |

Unchecked glucose production contributes to persistent hyperglycemia and hepatic insulin resistance. |

What Are the Clinical Endpoints of This Cascade?

The endpoint of this interconnected cascade of HPA axis dysregulation, GR resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and chronic inflammation is a cluster of conditions collectively known as metabolic syndrome. The clinical presentation is a direct reflection of the underlying pathophysiology.

- Central Obesity ∞ A result of the synergistic action of high cortisol and high insulin promoting visceral fat storage.

- Hyperglycemia ∞ Caused by hepatic insulin resistance and unchecked gluconeogenesis.

- Hypertension ∞ Driven by cortisol’s effects on blood vessels and fluid retention.

- Dyslipidemia ∞ Characterized by high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol, a direct consequence of altered liver metabolism and insulin resistance.

Understanding the long-term implications of stress requires this systems-biology perspective. It is an appreciation of how a psychological or environmental challenge becomes embedded in our biology, progressively remodeling our endocrine, immune, and metabolic systems at a cellular and even molecular level.

Therapeutic interventions, from lifestyle adjustments to advanced hormonal and peptide protocols, are designed to interrupt this cascade at various points, aiming to restore receptor sensitivity, re-establish healthy feedback loops, and return the body to a state of metabolic efficiency.

References

- An, S. & Kim, J. “Glucocorticoid receptor action in metabolic and neuronal function.” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, vol. 75, no. 1, 2018, pp. 1-13.

- Björntorp, P. “Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities?” Obesity Reviews, vol. 2, no. 2, 2001, pp. 73-86.

- Hewagalamulage, S. D. et al. “Stress, cortisol, and obesity ∞ a role for cortisol responsiveness in identifying individuals prone to obesity.” Domestic Animal Endocrinology, vol. 56, 2016, pp. S112-S120.

- Kyrou, I. & Tsigos, C. “Stress hormones ∞ physiological stress and regulation of metabolism.” Current Opinion in Pharmacology, vol. 9, no. 6, 2009, pp. 787-793.

- Osei, Francis, et al. “Association of primary allostatic load mediators and metabolic syndrome (MetS) ∞ A systematic review.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 13, 2022, p. 946740.

- Peckett, A. J. et al. “The role of glucocorticoid signaling in the etiology of metabolic disease.” Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, vol. 127, no. 3-5, 2011, pp. 188-197.

- Poole, L. et al. “A systematic review of the associations between post-traumatic stress disorder and metabolic syndrome.” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 202, 2016, pp. 124-135.

- Rabasa, C. & Dickson, S. L. “Impact of stress on metabolism and energy balance.” Current Opinion in Behavioural Sciences, vol. 9, 2016, pp. 71-77.

- Sapolsky, R. M. et al. “How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 21, no. 1, 2000, pp. 55-89.

- Yaribeygi, Habib, and Toktam Sahraei. “Molecular mechanisms linking stress and insulin resistance.” EXCLI Journal, vol. 17, 2018, pp. 464-475.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory you inhabit. It connects the feelings you experience to the intricate functions of your internal systems. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active awareness.

How does this map relate to your own personal landscape? Where do you see the intersections between the pressures in your life and the signals your body is sending? Recognizing these connections is the foundational act of taking control. The path forward is one of personalized calibration, a process that begins with understanding the specific ways your body has adapted and what it needs to restore its innate state of health and function.