Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A subtle shift in energy, a fog that clouds your thinking, a change in your body’s resilience that leaves you feeling disconnected from the person you used to be. This experience, this deep-seated sense that your internal calibration is off, is a valid and important signal.

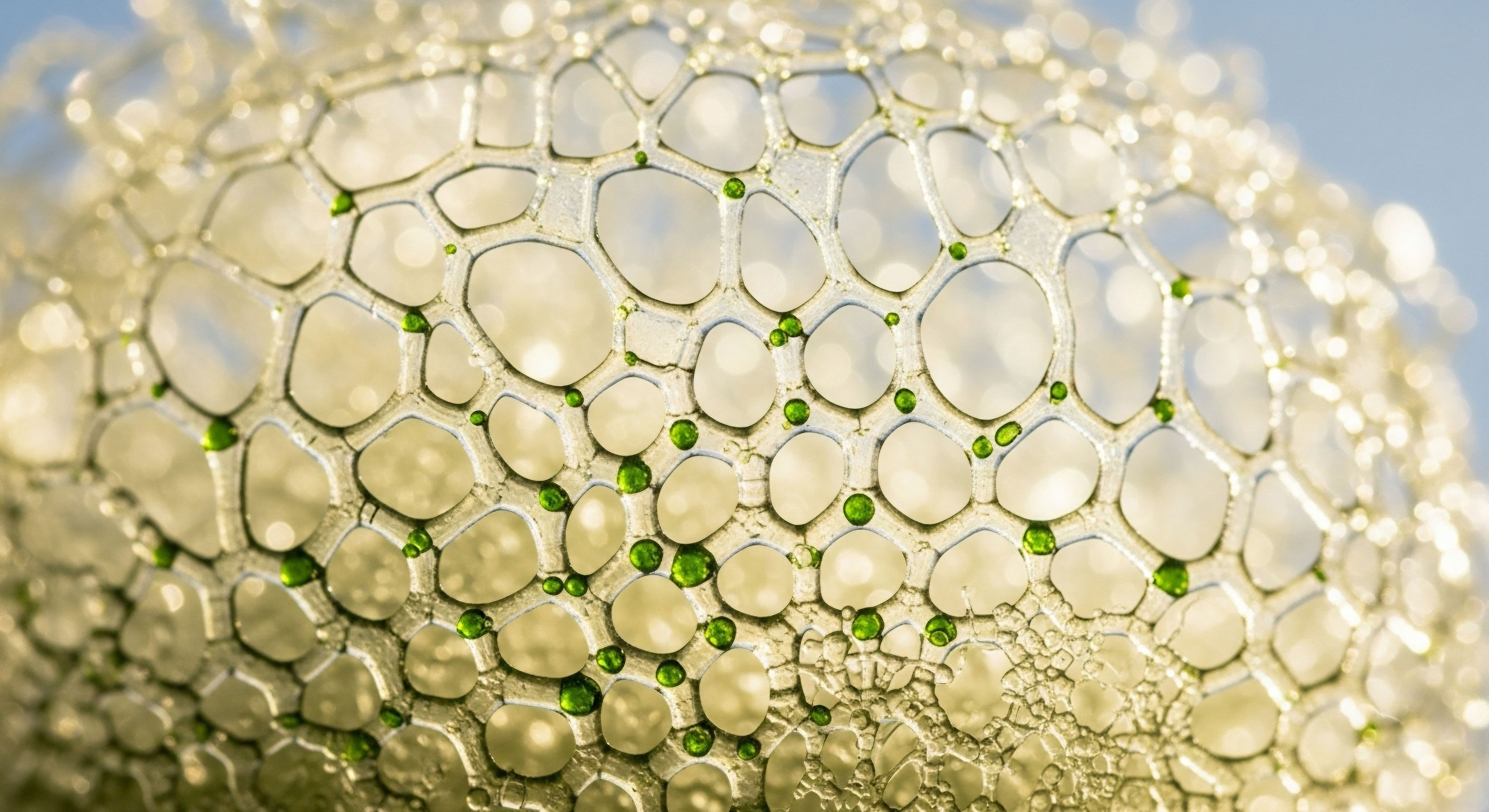

It is your body communicating a disruption in its most fundamental operating system. We can begin to understand this experience by looking at the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal axis, or HPG axis. This is the primary communication network governing your hormonal health, a three-part system that acts as the master conductor of your vitality, metabolism, and sense of well-being.

The HPG axis is an elegant, self-regulating feedback loop. At the top, residing deep within the brain, is the hypothalamus. It acts as the system’s command center, sending out a pulsed signal in the form of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

This signal travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the master gland, instructing it to release two other messenger hormones into the bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones then travel to the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women.

In response, the gonads produce the sex hormones that are critical for systemic health ∞ primarily testosterone in men and estrogen and progesterone in women. These end-product hormones then circulate throughout the body, carrying out their vast array of functions. They also send feedback signals back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, informing them to adjust the production of GnRH, LH, and FSH. This constant communication ensures hormonal levels remain in a healthy, functional range.

The HPG axis functions as a precise biological thermostat, constantly adjusting hormonal output to maintain systemic equilibrium and vitality.

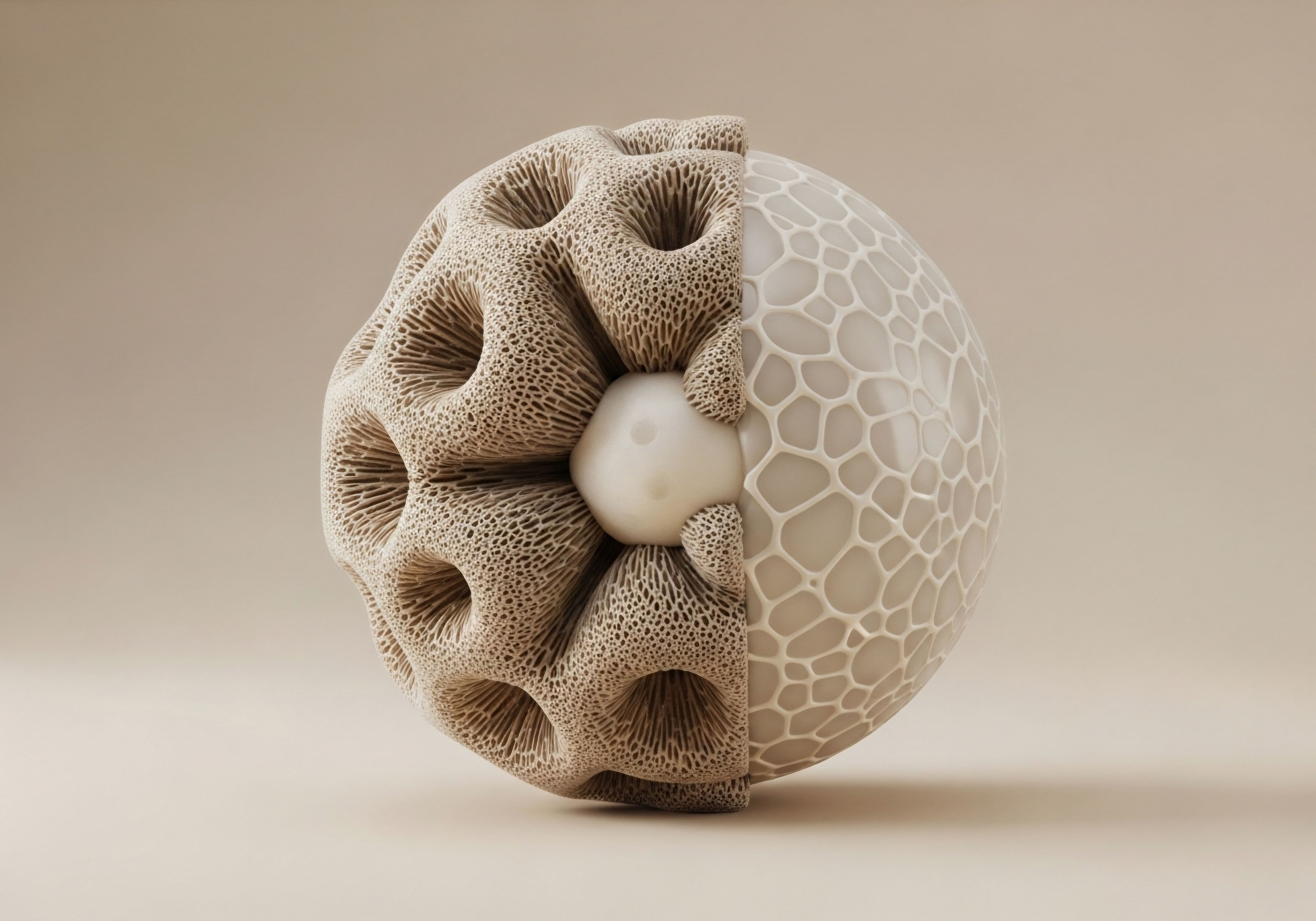

Dysregulation occurs when this communication breaks down. The signals can become weak, erratic, or unresponsive. The hypothalamus might reduce its GnRH pulses, the pituitary might fail to respond correctly, or the gonads may lose their ability to produce hormones efficiently. This is not a simple on-or-off switch.

It is a degradation of signal quality. The long-term implications of this breakdown extend far beyond reproductive health. Because sex hormones regulate everything from brain function to bone density and metabolic rate, a persistent communication failure in the HPG axis creates cascading consequences throughout the entire body. Addressing the root of this signaling failure is the first step toward reclaiming your biological integrity.

The Core Components of Your Endocrine Command Center

Understanding the individual roles within this axis helps clarify how a disruption in one area can affect the entire system. Each component has a distinct job, and their synchronized action is what creates hormonal balance. Their collective function is what allows your body to adapt, repair, and thrive.

The Hypothalamus the Initiator

The hypothalamus is the starting point of the hormonal cascade. It constantly monitors the body’s internal environment, including stress levels, nutritional status, and existing hormone concentrations. Based on this incoming data, it releases GnRH in a pulsatile manner. The frequency and amplitude of these pulses are a critical form of information for the pituitary gland.

Chronic stress or poor nutrition can directly alter these pulses, representing one of the earliest forms of HPG axis dysregulation. The system is designed for sensitivity, making it an accurate reporter of your overall state of health.

The Pituitary Gland the Amplifier

The pituitary gland receives the GnRH signal and translates it into a broader, more powerful message. It amplifies the initial command by releasing LH and FSH into the general circulation. LH is the primary stimulus for testosterone production in the Leydig cells of the testes and for ovulation and progesterone production in the ovaries.

FSH is instrumental for sperm maturation in men and for the development of ovarian follicles, which are the source of estrogen in women. A pituitary that is under-responsive to GnRH will fail to send adequate signals to the gonads, even if the initial command from the hypothalamus is strong.

The Gonads the Responders and Manufacturers

The testes and ovaries are the production centers of the axis. They respond to the LH and FSH signals by synthesizing and releasing testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone. These hormones are the ultimate effectors, interacting with receptors in nearly every tissue of the body. They influence muscle growth, bone maintenance, cognitive processes, mood regulation, and metabolic health.

A decline in gonadal function, often associated with aging, means that even with strong signals from the brain, the capacity to produce adequate hormone levels is diminished. This represents a different point of failure within the same interconnected system.

Intermediate

When the precise signaling of the HPG axis becomes chronically disrupted, the consequences manifest as a collection of symptoms that can degrade one’s quality of life. This state, clinically referred to as hypogonadism in cases of low sex hormone output, is a systemic issue.

The failure is not isolated to the gonads; it reflects a breakdown in the entire communication pathway. Understanding the clinical protocols for addressing this dysregulation involves appreciating the goal of restoring this communication. The therapeutic objective is to re-establish physiological hormone levels and, in doing so, correct the downstream metabolic and psychological disturbances that arise from the deficiency.

For men, this dysregulation often presents as a gradual decline in energy, libido, cognitive focus, and physical strength. For women, particularly during the perimenopausal and postmenopausal transitions, the fluctuations and eventual decline in estrogen and progesterone lead to symptoms like hot flashes, mood instability, sleep disturbances, and changes in body composition.

In both sexes, these experiences are direct results of the body losing the organizing influence of its primary sex hormones. The clinical approach, therefore, must be tailored to the specific nature of the hormonal deficit and the individual’s health profile. It involves careful diagnosis through blood work to confirm consistently low hormone levels and to rule out other conditions.

The subsequent treatment protocols are designed to supply the body with the necessary hormones in a manner that mimics its natural rhythms as closely as possible.

Restoring Male Hormonal Balance Clinical Protocols

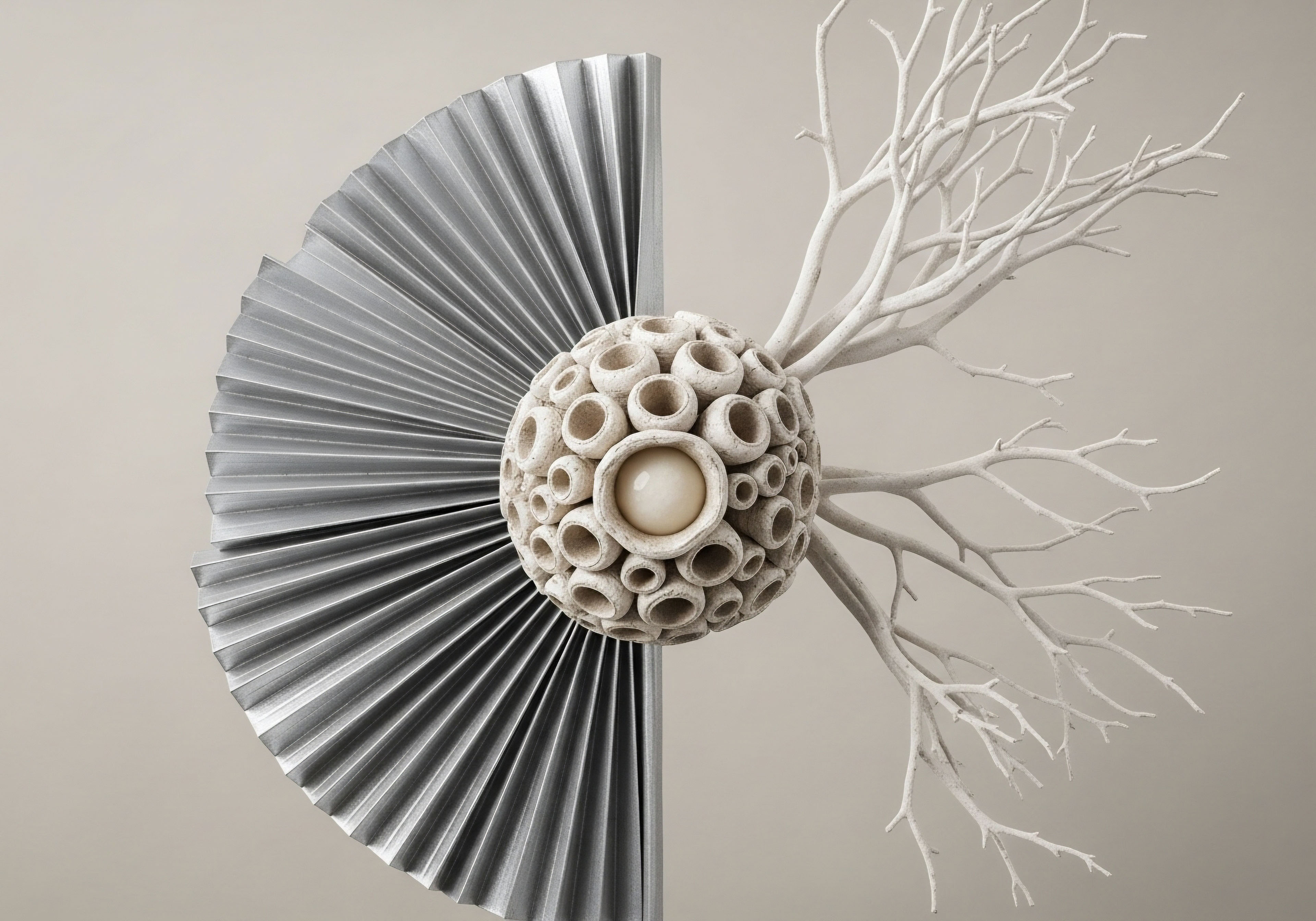

In men diagnosed with hypogonadism, the primary intervention is Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). The goal of TRT is to restore serum testosterone levels to a healthy physiological range, thereby alleviating symptoms and mitigating long-term health risks like osteoporosis and metabolic syndrome. The approach is systematic, involving not just the administration of testosterone but also the management of its metabolic byproducts and the preservation of the HPG axis’s residual function.

Core TRT Protocols

The administration of testosterone can be achieved through several methods, each with its own pharmacokinetic profile. The choice of delivery method is often based on patient preference, cost, and the desired stability of hormone levels.

- Intramuscular Injections Testosterone Cypionate or Enanthate are long-acting esters administered via injection. A standard protocol might involve weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate (200mg/ml). This method is cost-effective and produces predictable peaks and troughs in testosterone levels.

- Subcutaneous Injections Smaller, more frequent injections of Testosterone Cypionate can be administered into the subcutaneous fat. This method can lead to more stable serum levels and is often preferred by patients for its ease of self-administration.

- Transdermal Gels and Creams These are applied daily to the skin, providing a steady absorption of testosterone. They mimic the body’s natural diurnal rhythm of testosterone production. Their use requires caution to prevent transference to others.

- Pellet Therapy Testosterone pellets are implanted under the skin and release the hormone slowly over a period of three to six months. This method offers convenience by eliminating the need for frequent dosing.

Ancillary Medications a Systems Approach

A comprehensive TRT protocol addresses the broader hormonal environment. Testosterone can be converted into estrogen via the aromatase enzyme. While some estrogen is necessary for male health, excessive levels can lead to side effects. Therefore, ancillary medications are often included.

- Anastrozole This is an aromatase inhibitor, an oral medication taken to block the conversion of testosterone to estrogen. Its inclusion helps manage potential side effects like gynecomastia and water retention, ensuring a balanced hormonal profile.

- Gonadorelin or HCG Exogenous testosterone administration suppresses the HPG axis, reducing the pituitary’s release of LH and FSH. This can lead to testicular atrophy and a cessation of endogenous testosterone production. Gonadorelin, a GnRH analogue, or Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG), which mimics LH, is used to directly stimulate the testes. This preserves testicular function and size, and maintains a degree of natural hormonal activity within the system.

- Enclomiphene or Clomid These are Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs). They can be used to block estrogen’s negative feedback at the pituitary, thereby increasing the gland’s output of LH and FSH. This stimulates the testes to produce more of their own testosterone. This approach is often used in men who wish to preserve fertility or as part of a protocol to restart the HPG axis after discontinuing TRT.

Navigating Female Hormonal Transitions

For women, hormonal therapy is most commonly used to manage the symptoms of perimenopause and menopause. As ovarian function declines, the production of estrogen and progesterone becomes erratic and then falls, leading to significant systemic effects. Hormonal optimization protocols are designed to supplement these declining hormones, providing stability and relief.

Hormonal optimization therapies are designed to restore the body’s signaling integrity, addressing the root causes of symptoms rather than just masking them.

Tailored Protocols for Women

The approach for women is highly individualized, based on their menopausal status and specific symptoms.

- Progesterone Therapy Progesterone is often prescribed for perimenopausal women to help regulate cycles and improve mood and sleep. In postmenopausal women, it is used in combination with estrogen to protect the uterine lining.

- Estrogen Therapy Estrogen is highly effective at relieving vasomotor symptoms like hot flashes and night sweats. It is available in various forms, including patches, gels, and pills.

- Low-Dose Testosterone Therapy Women also produce and require testosterone for energy, libido, and cognitive function. Low-dose Testosterone Cypionate, typically administered via weekly subcutaneous injections (0.1-0.2ml), can be a valuable addition to a woman’s hormone protocol. It helps restore vitality and mental clarity that estrogen and progesterone alone may not fully address.

What Are the Key Differences in TRT Formulations?

The choice between different testosterone delivery systems involves a trade-off between convenience, cost, and the stability of hormone levels. Understanding these differences is a key part of creating a personalized treatment plan.

| Formulation | Dosing Frequency | Hormone Level Stability | Primary Advantage | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intramuscular Injection | Weekly or Bi-weekly | Moderate (Peaks and Troughs) | High efficacy, low cost | Requires injection, fluctuating levels |

| Subcutaneous Injection | 2-3 times per week | High | Very stable levels, easy self-administration | Requires frequent injections |

| Transdermal Gel | Daily | High (Mimics Diurnal Rhythm) | Non-invasive, stable levels | Risk of transference, potential for skin irritation |

| Subdermal Pellets | Every 3-6 months | High (after initial period) | Extreme convenience | Requires a minor surgical procedure for insertion/removal |

Academic

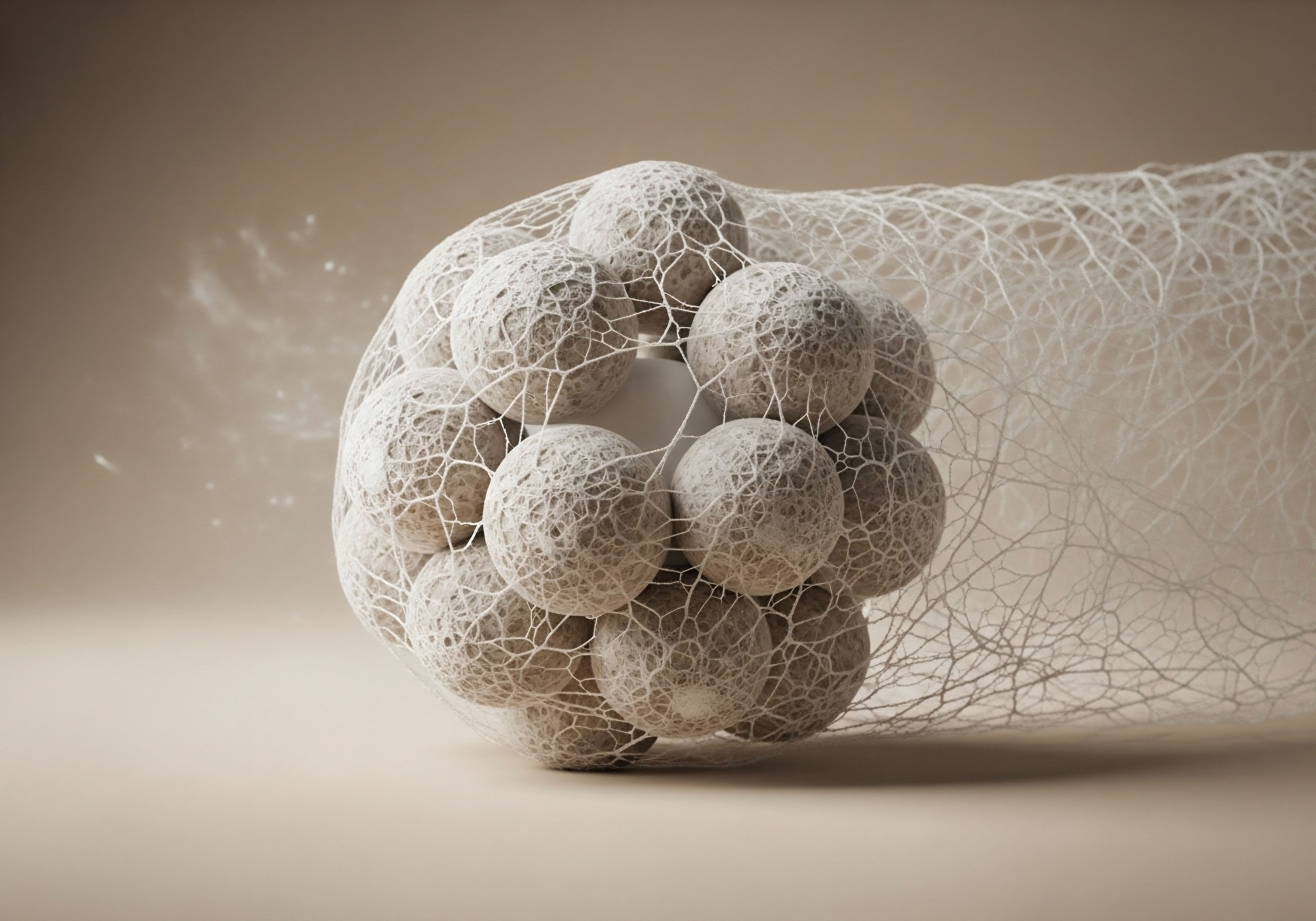

The long-term sequelae of unaddressed Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis dysregulation represent a progressive erosion of systemic homeostasis. This condition, particularly when it results in chronic hypogonadism, initiates a cascade of pathophysiological processes that extend far beyond the reproductive system.

The decline in anabolic and neuroprotective signaling from sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen acts as a catalyst for interconnected pathologies, most notably metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative processes, and the structural decline of the musculoskeletal system. The academic exploration of these implications requires a systems-biology perspective, viewing the endocrine disruption as a central node failure that radiates dysfunction throughout the body’s metabolic, inflammatory, and neural networks.

The core of this systemic decline lies in the loss of hormonal signaling integrity. Testosterone and estrogen are not merely reproductive hormones; they are powerful regulators of cellular function in a vast array of tissues. Their receptors are found in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, liver, bone, vascular endothelium, and throughout the central nervous system.

Consequently, a sustained deficit in these hormones removes a critical layer of metabolic and cellular protection, leaving these systems vulnerable to age-related and lifestyle-driven stressors. The resulting clinical picture is one of accelerated aging, where the risks for chronic diseases are significantly amplified.

The Metabolic Derangement Cascade

One of the most well-documented consequences of HPG axis dysregulation is the development of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions including visceral obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. The loss of adequate testosterone signaling in men is a primary driver of this pathology.

Testosterone directly influences body composition by promoting muscle protein synthesis and inhibiting the differentiation of adipocyte precursor cells. When testosterone levels fall, a metabolic shift occurs ∞ anabolic signaling in muscle tissue decreases, leading to sarcopenia, while lipogenic (fat-storing) activity in adipose tissue increases, particularly in the visceral depots of the abdomen.

From Hormone Deficit to Insulin Resistance

Visceral adipose tissue is metabolically active and highly inflammatory. It secretes a range of adipokines and cytokines that directly interfere with insulin signaling. This leads to systemic insulin resistance, a state where cells in the muscle, fat, and liver become less responsive to insulin’s effects.

The pancreas compensates by producing more insulin, resulting in hyperinsulinemia. This state is a precursor to type 2 diabetes and a direct contributor to vascular damage. The connection is bidirectional; obesity itself can suppress the HPG axis, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of metabolic and endocrine dysfunction. Clinical interventions with TRT in hypogonadal men have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce visceral fat mass, demonstrating the direct regulatory role of testosterone in glucose metabolism.

Chronic HPG axis dysregulation systematically dismantles metabolic health, creating a direct pathway to insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease.

Cardiovascular Implications

The link between low testosterone and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is multifactorial. The components of metabolic syndrome are themselves major risk factors for CVD. In addition, testosterone has direct effects on the cardiovascular system. It promotes vasodilation, which helps maintain healthy blood pressure.

It also influences lipid profiles; low testosterone is often associated with elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides, and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. The chronic inflammatory state promoted by visceral adiposity further contributes to the development of atherosclerosis, the underlying cause of most heart attacks and strokes. The dysregulation of the HPG axis, therefore, creates a pro-atherogenic and pro-inflammatory environment, significantly increasing long-term cardiovascular risk.

How Does HPG Dysregulation Impact Neurological Health?

The brain is a major target for sex hormones. The HPG axis’s influence extends deeply into the central nervous system, affecting everything from mood and motivation to cognitive function and neuronal survival. The long-term absence of these hormonal signals contributes to a decline in neurological resilience and may accelerate neurodegenerative processes.

Cognitive Function and Neuroinflammation

Both testosterone and estrogen have significant neuroprotective roles. They support synaptic plasticity, promote the growth of new neurons (neurogenesis), and modulate the activity of key neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. A decline in these hormones, as seen in untreated hypogonadism or menopause, is strongly correlated with symptoms of cognitive fog, memory lapses, and reduced executive function.

Research suggests a link between long-term sex hormone deficiencies and an increased risk for developing neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. These hormones help regulate the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides, the protein fragments that form plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Their absence may impair this clearance mechanism while simultaneously promoting a state of chronic neuroinflammation, another key factor in the disease’s progression.

Mood and Affective Disorders

The connection between hormonal imbalance and mood disturbances is well-established. Low testosterone in men is a known contributor to depression, apathy, and irritability. The fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone during perimenopause are also strongly linked to an increased incidence of anxiety and depression.

These hormones interact with the brain’s emotional regulation circuits, including the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Their dysregulation can disrupt the delicate balance of neurotransmitters that sustain a stable mood. The interaction between the HPG axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s stress response system, is also critical.

Chronic stress can suppress HPG function, and low sex hormones can, in turn, impair the body’s ability to effectively manage the stress response, creating another vicious cycle that impacts mental health.

The Erosion of Structural and Systemic Integrity

The anabolic signals from the HPG axis are fundamental to maintaining the body’s physical structure. The long-term absence of these signals leads to a gradual decay of the musculoskeletal system and a weakening of other physiological processes.

| System Affected | Consequence of HPG Dysregulation | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal System | Osteoporosis / Osteopenia | Sex hormones regulate the balance between osteoblasts (bone-building cells) and osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells). Low levels lead to net bone loss and increased fracture risk. |

| Muscular System | Sarcopenia (Muscle Loss) | Testosterone is a primary driver of muscle protein synthesis. Its absence leads to a loss of muscle mass, strength, and physical function, increasing frailty. |

| Hematopoietic System | Anemia | Testosterone stimulates the production of erythropoietin (EPO) in the kidneys, a hormone that drives red blood cell production. Low testosterone can lead to mild anemia. |

| Immune System | Immune Dysregulation | Sex hormones modulate immune function. Imbalances can contribute to a pro-inflammatory state and may alter the body’s response to pathogens and injury. |

Growth Hormone and Peptide Science

The HPG axis does not operate in isolation. Its function is closely tied to other endocrine systems, including the Growth Hormone (GH) axis. GH and its downstream mediator, Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1), are critical for tissue repair, cell regeneration, and maintaining a healthy body composition.

HPG axis dysregulation can negatively impact the GH axis. Peptide therapies, which use specific signaling molecules to stimulate the body’s own hormone production, represent an advanced clinical strategy to address these interconnected declines. Peptides like Sermorelin, Ipamorelin, and CJC-1295 are secretagogues, meaning they signal the pituitary gland to release more GH. This approach can help counteract the sarcopenia, fat accumulation, and decline in tissue repair associated with hormonal deficiencies, working synergistically with HPG axis restoration to improve overall systemic health.

References

- Bhasin, S. et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715 ∞ 1744.

- Rosano, G. M. C. et al. “Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation on the metabolic profile of patients affected by diabetes mellitus-associated late onset hypogonadism.” Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, vol. 26, no. 2, 2016, pp. 169-75.

- Tsujimura, A. “The Relationship between Testosterone Deficiency and Men’s Health.” The World Journal of Men’s Health, vol. 31, no. 2, 2013, pp. 126-135.

- Traish, A. M. et al. “The dark side of testosterone deficiency ∞ I. Metabolic syndrome and erectile dysfunction.” Journal of Andrology, vol. 30, no. 1, 2009, pp. 10-22.

- Kelly, D. M. & Jones, T. H. “Testosterone and obesity.” Obesity Reviews, vol. 16, no. 7, 2015, pp. 581-606.

- Vermeulen, A. et al. “A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 84, no. 10, 1999, pp. 3666-3672.

- Behre, H. M. et al. “EAU Guidelines on Male Hypogonadism.” European Association of Urology, 2018.

- Pye, S. R. et al. “Late-onset hypogonadism and mortality in aging men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 99, no. 4, 2014, pp. 1357-1366.

- Glintborg, D. & Andersen, M. “An update on the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome.” Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 8, no. 1, 2017, pp. 3-17.

- Herrmann, M. et al. “Testosterone and the brain.” Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 11, 2020.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory, connecting symptoms to systems and explaining the profound, cascading effects of hormonal signaling failure. You have seen how a disruption in one central communication axis can echo through your metabolism, your mind, and your physical structure. This knowledge is the foundational step. It transforms vague feelings of decline into a clear, understandable physiological narrative. It validates your personal experience with objective, evidence-based science.

This understanding is where the journey toward reclaiming your vitality truly begins. The path forward is one of personalized investigation and action. Your unique biology, lifestyle, and health history will determine the specific nature of your needs.

The next step involves a partnership with a clinical expert who can help you interpret your body’s signals, analyze your specific data, and construct a protocol designed to restore your unique hormonal equilibrium. You possess the most important dataset ∞ your own lived experience. Combining that with precise clinical data creates a powerful blueprint for building a more resilient, functional, and vibrant future.