Fundamentals

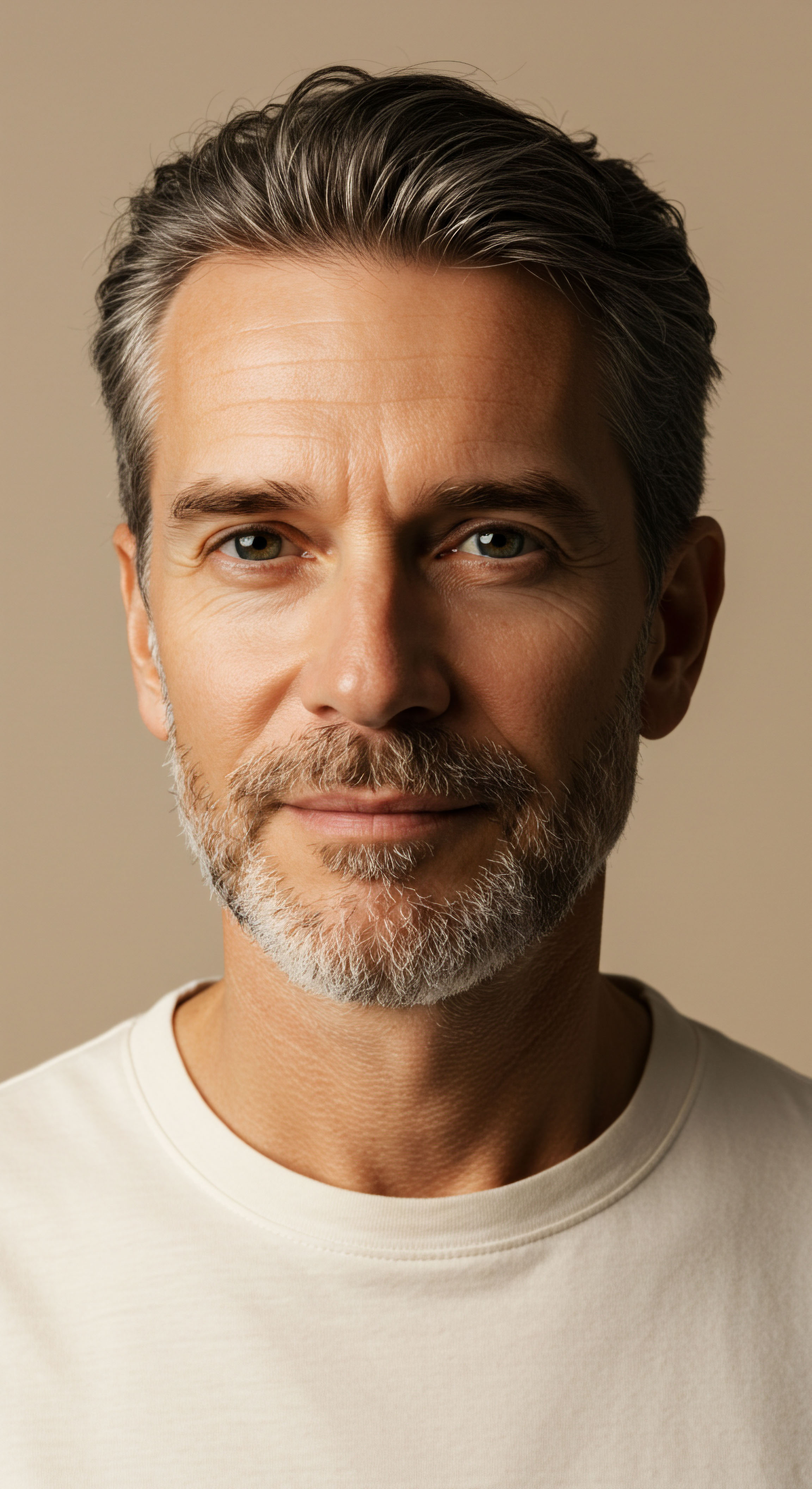

Observing a change in your body, such as a reduction in testicular size, can be a deeply personal and unsettling experience. It often brings with it a cascade of questions and concerns that touch upon the very core of male identity, vitality, and health.

This physical alteration is frequently a quiet signal from your body’s intricate communication network, pointing toward a shift in its internal environment. Understanding this signal is the first step toward addressing the root cause and reclaiming a sense of control over your biological systems. The experience is not merely a cosmetic concern; it is a valid biological marker that warrants careful and compassionate investigation.

Testicular atrophy, the clinical term for the shrinkage of the testes, is fundamentally a sign of reduced cellular activity. The testes have two primary functions ∞ the production of sperm (spermatogenesis) and the synthesis of androgens, with testosterone being the most significant.

When the testes decrease in size, it suggests that one or both of these critical manufacturing processes have been downregulated. This is not an isolated event. It is a direct consequence of disruptions within a sophisticated biological control system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This axis is the command-and-control pathway for male reproductive and hormonal health.

The Body’s Internal Messaging System

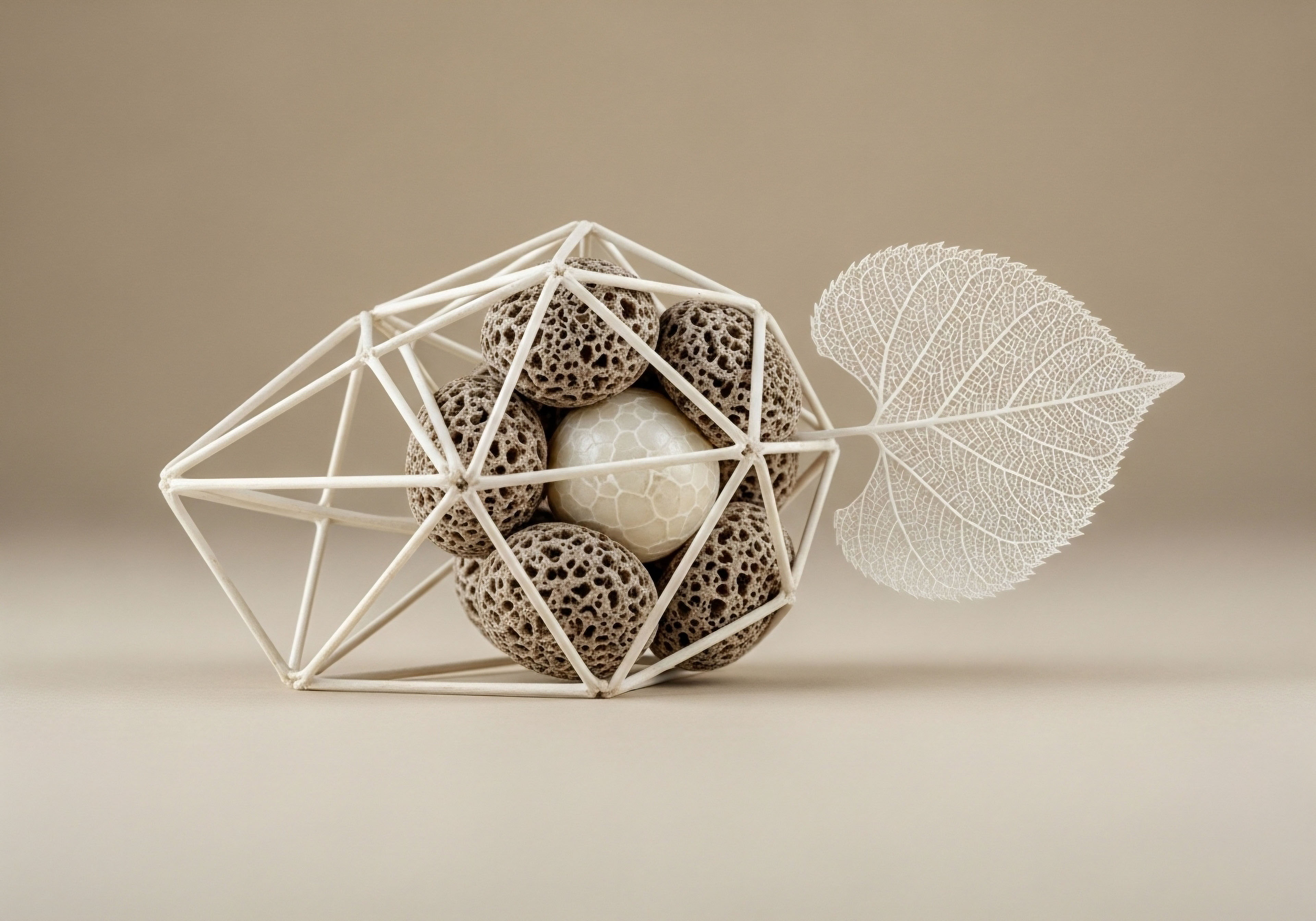

To appreciate the implications of testicular atrophy, it is helpful to visualize the HPG axis as a continuous feedback loop, much like a thermostat regulating a room’s temperature. The process begins in the brain.

- The Hypothalamus ∞ Located at the base of the brain, the hypothalamus acts as the system’s sensor. It monitors the levels of testosterone in the bloodstream. When it detects that levels are low, it releases a signaling molecule called Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

- The Pituitary Gland ∞ GnRH travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, also in the brain. The pituitary acts as the central command. In response to GnRH, it secretes two other critical hormones into the bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

- The Testes (Gonads) ∞ LH and FSH travel through the circulation to the testes, delivering their instructions. LH directly stimulates a specific group of cells, the Leydig cells, to produce testosterone. FSH, in concert with testosterone, stimulates the Sertoli cells to support sperm production.

This entire system is self-regulating. As testosterone levels rise in the blood, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland detect this increase and, in turn, reduce their output of GnRH, LH, and FSH. This negative feedback ensures that testosterone production remains within a healthy, stable range.

Testicular atrophy occurs when this signaling pathway is broken or suppressed. Without the consistent stimulatory signals of LH and FSH, the cellular machinery within the testes becomes dormant, leading to a reduction in both size and function.

The shrinking of the testes is a physical manifestation of a disruption in the hormonal conversation between the brain and the gonads.

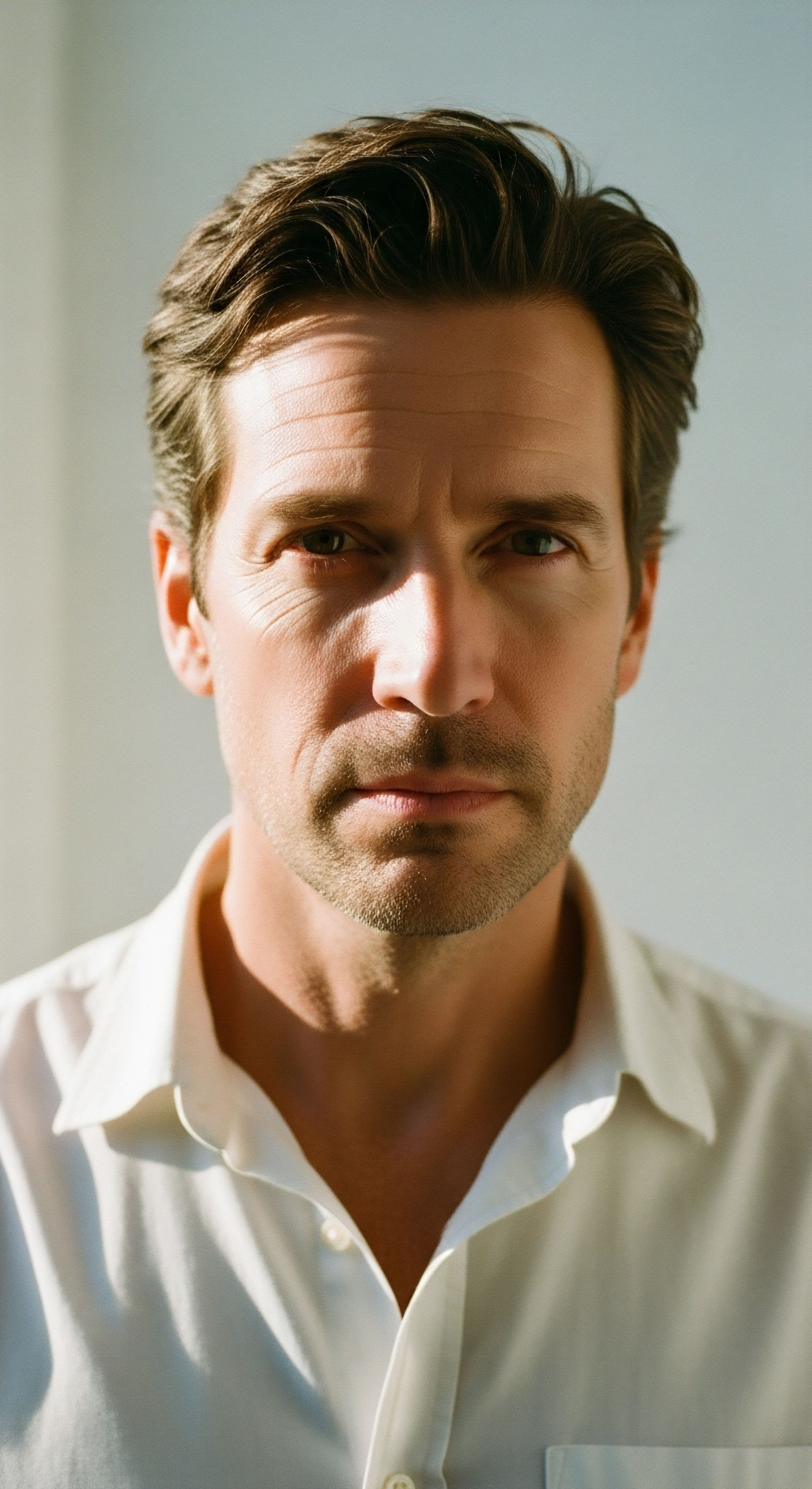

What Causes the System to Falter?

The interruption of the HPG axis can originate from different points in the pathway, which helps clinicians classify the underlying issue. Understanding the source of the problem is essential for determining the correct course of action.

- Primary Hypogonadism ∞ This term describes a problem originating within the testes themselves. The brain is sending the correct signals (high levels of LH and FSH), but the testes are unable to respond adequately. It is akin to the thermostat sending a signal to the furnace, but the furnace is broken. Causes can include genetic conditions (like Klinefelter syndrome), physical injury to the testes, infections like mumps orchitis, or damage from cancer treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation.

- Secondary Hypogonadism ∞ This indicates that the problem lies higher up in the command chain, within the brain (hypothalamus or pituitary gland). The testes are perfectly capable of producing testosterone, but they are not receiving the necessary instructions. In this case, levels of LH and FSH are low, leading to testicular dormancy. This can be caused by pituitary tumors, head injuries, certain medications (most notably opioids and anabolic steroids), or severe systemic illness.

One of the most common external causes of secondary hypogonadism and subsequent testicular atrophy is the use of exogenous anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS). When a man introduces high levels of synthetic testosterone or similar compounds into his body, the hypothalamus and pituitary perceive an overabundance of androgens.

Their natural response is to shut down the production of GnRH, LH, and FSH completely. Without the stimulation from LH, the Leydig cells cease their production of endogenous testosterone, and the testes begin to shrink from disuse. This is a predictable physiological response, not a sign of permanent damage in all cases, but it vividly illustrates the power of the HPG axis feedback loop.

The journey to understanding testicular atrophy begins with recognizing it as a meaningful sign from the body. It prompts a deeper look into the intricate hormonal symphony that governs so much of male health. By identifying where the communication has broken down, it becomes possible to formulate a strategy aimed at restoring the system’s balance and function.

Intermediate

When testicular atrophy persists, it is a definitive indicator of hypogonadism ∞ a clinical state where the testes fail to produce adequate levels of testosterone to meet the body’s needs. The long-term implications of this condition extend far beyond reproductive health, permeating every biological system.

The gradual decline in testosterone sets off a chain reaction of metabolic, physical, and psychological changes that can profoundly diminish a man’s quality of life and long-term health. Addressing these changes requires a sophisticated understanding of the underlying hormonal deficit and a targeted approach to restoring physiological balance.

The consequences of sustained low testosterone are systemic because androgen receptors are found in cells throughout the body, including in the brain, bone, muscle, fat tissue, and cardiovascular system. The absence of adequate testosterone signaling leads to a progressive dysregulation of these tissues. This is not an overnight process; it is a slow erosion of function that can manifest in a constellation of symptoms that are often mistakenly attributed to normal aging.

The Systemic Cascade of Low Testosterone

A chronic state of hypogonadism initiates a series of predictable and interconnected health issues. These consequences are not separate symptoms but are linked components of a single underlying endocrine disorder. Understanding this web of effects is the first step toward appreciating the necessity of a comprehensive treatment protocol.

Metabolic and Body Composition Derangements

Testosterone is a powerful metabolic regulator. It promotes the growth of lean muscle mass and influences how the body stores and utilizes energy. In a low-testosterone state, this regulation is lost, leading to several adverse changes:

- Sarcopenia ∞ This is the clinical term for the loss of muscle mass and strength. Testosterone directly stimulates muscle protein synthesis. Without it, the body’s ability to maintain and build muscle is impaired, leading to physical weakness, reduced physical performance, and a lower metabolic rate.

- Increased Adiposity ∞ Testosterone inhibits the creation of new fat cells (adipocytes) and promotes the breakdown of stored fat. When testosterone levels fall, the body’s metabolism shifts toward fat storage, particularly visceral fat ∞ the metabolically active fat that accumulates around the abdominal organs.

- Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome ∞ The accumulation of visceral fat is a primary driver of insulin resistance, a condition where the body’s cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin. This state is a precursor to type 2 diabetes and is a core component of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions (including high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol levels) that collectively increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Skeletal and Cardiovascular Health

The integrity of the skeletal and cardiovascular systems is also highly dependent on adequate androgen levels. The long-term absence of testosterone can have severe structural and functional consequences.

A sustained lack of testosterone compromises bone density and vascular health, increasing the risk for fractures and cardiovascular events.

Bone is a dynamic tissue that is constantly being broken down and rebuilt. Testosterone plays a direct role in this process, and it is also converted to estrogen in bone tissue, which is critical for inhibiting bone resorption. Chronic hypogonadism disrupts this balance, leading to a net loss of bone mineral density.

Over time, this results in osteopenia (low bone mass) and can progress to osteoporosis, a condition characterized by brittle, porous bones that are highly susceptible to fracture. Hypogonadism is one of the most common identifiable causes of osteoporosis in men.

The cardiovascular system is also affected. Low testosterone is associated with a number of risk factors for heart disease, including unfavorable lipid profiles (higher LDL cholesterol, lower HDL cholesterol), increased inflammatory markers, and endothelial dysfunction ∞ a condition where the lining of the blood vessels becomes less flexible and unable to dilate properly. These factors contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaque in the arteries that can lead to heart attacks and strokes.

Clinical Protocols for Hormonal Recalibration

When testicular atrophy and symptomatic hypogonadism are confirmed through clinical evaluation and laboratory testing (typically requiring at least two separate morning blood tests showing low total testosterone), a protocol to restore hormonal balance is indicated. The goal of such a protocol is to re-establish testosterone levels within a healthy physiological range, thereby mitigating the long-term health consequences of the deficiency.

The Foundational Protocol Testosterone Replacement Therapy

The cornerstone of treatment is Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). The most common and reliable method involves weekly intramuscular injections of a testosterone ester, such as Testosterone Cypionate. This approach provides stable and predictable hormone levels, avoiding the daily fluctuations that can occur with gels or patches.

However, a sophisticated protocol does more than just replace testosterone. It also addresses the downstream effects of introducing an external source of androgens. A well-designed TRT program often includes adjunctive medications to maintain the body’s natural hormonal signaling and to manage potential side effects.

| Component | Agent | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Androgen Replacement | Testosterone Cypionate | Directly replaces the body’s primary androgen, binding to androgen receptors throughout the body. | To restore testosterone to physiological levels, alleviating symptoms and preventing long-term complications of hypogonadism. |

| HPG Axis Support | Gonadorelin (or hCG) | Mimics the action of GnRH (Gonadorelin) or LH (hCG), directly stimulating the testes. | To prevent further testicular atrophy by keeping the testes’ Leydig cells active, preserving testicular size and maintaining some natural testosterone production and fertility potential. |

| Estrogen Management | Anastrozole | An aromatase inhibitor that blocks the conversion of testosterone to estradiol. | To manage estrogen levels and prevent side effects like gynecomastia (breast tissue development) and water retention, which can occur when testosterone levels are elevated. |

Why Are Adjunctive Medications Used?

The inclusion of agents like Gonadorelin and Anastrozole transforms simple replacement into a more holistic form of hormonal optimization. When a man starts TRT, his brain’s natural production of LH and FSH ceases due to the negative feedback loop. Without LH stimulation, the testes will become inactive and shrink further.

Gonadorelin, a synthetic form of GnRH, provides a pulsatile signal to the pituitary, or more commonly, agents like hCG directly mimic LH, keeping the testicular machinery “on.” This is particularly important for men who wish to preserve fertility or simply avoid the psychological and physical effects of complete testicular shutdown.

Similarly, as testosterone levels are restored, some of that testosterone will naturally be converted into estradiol by the enzyme aromatase. While some estrogen is essential for male health (particularly for bone density and libido), excessive levels can lead to unwanted side effects. Anastrozole is used judiciously to modulate this conversion, keeping estradiol within an optimal range. The goal is balance, not elimination.

By addressing the primary deficiency with testosterone and supporting the body’s natural systems with adjunctive therapies, a modern clinical protocol aims to do more than just raise a number on a lab report. It seeks to restore the intricate hormonal and metabolic balance that is essential for long-term health and vitality.

Academic

The clinical sequelae of testicular atrophy and the resultant hypogonadal state represent a profound disruption of male physiology, extending into the domains of metabolic regulation, inflammatory signaling, and neurocognitive function. A deeper, systems-biology perspective reveals that the decline in androgen production is not merely a loss of a single hormone but the destabilization of a complex, interconnected network.

The long-term implications are rooted in the loss of testosterone’s role as a master metabolic and anti-inflammatory regulator. This section will explore the intricate pathophysiological mechanisms linking androgen deficiency to the development of cardiometabolic disease and the potential for neuroinflammation and cognitive decline, providing a molecular basis for the systemic effects observed clinically.

The Androgen-Deficient Milieu and Cardiometabolic Collapse

The strong epidemiological association between low testosterone and metabolic syndrome is underpinned by specific molecular and cellular mechanisms. Testosterone exerts a powerful influence on body composition and glucose homeostasis. Its absence creates a permissive environment for the development of a pro-inflammatory, insulin-resistant state that is the foundation of cardiometabolic disease.

How Does Low Testosterone Drive Visceral Adiposity and Insulin Resistance?

Androgen receptors are expressed in pre-adipocytes (immature fat cells) and mature adipocytes. Testosterone signaling influences adipocyte differentiation and lipid metabolism. Specifically, androgens appear to inhibit the differentiation of pre-adipocytes into mature, lipid-storing fat cells, particularly in the visceral depots. They also promote lipolysis (the breakdown of stored fat) by increasing the number of beta-adrenergic receptors on fat cells, making them more sensitive to the fat-releasing signals of catecholamines like adrenaline.

In a state of androgen deficiency, this regulatory control is lost. The balance shifts in favor of adipogenesis and lipid accumulation, leading to the expansion of visceral adipose tissue (VAT). VAT is not an inert storage depot; it is a highly active endocrine organ that secretes a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6).

These cytokines have direct local and systemic effects. They interfere with the insulin signaling cascade in muscle and liver cells, a key mechanism in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. TNF-α, for example, can phosphorylate the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) on serine residues, which inhibits its normal function and blunts the cell’s response to insulin. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ low testosterone promotes visceral fat gain, which in turn drives inflammation and insulin resistance, further worsening the metabolic profile.

The loss of testosterone initiates a self-perpetuating cycle of visceral fat accumulation, chronic low-grade inflammation, and insulin resistance, which are the central pillars of cardiometabolic disease.

This inflammatory state also contributes to endothelial dysfunction. The chronic circulation of inflammatory cytokines impairs the production of nitric oxide (NO) in the vascular endothelium, a critical molecule for vasodilation and vascular health. The result is increased arterial stiffness and a higher risk of hypertension and atherosclerotic plaque formation.

| Stage | Molecular and Cellular Events | Systemic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Initiating Event | Reduced testosterone signaling to androgen receptors. | Primary or secondary hypogonadism. |

| Adipose Tissue Dysregulation | Decreased inhibition of pre-adipocyte differentiation; reduced lipolysis. | Preferential accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT). |

| Inflammatory Response | Increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) from VAT. | Chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation. |

| Metabolic Derangement | Cytokine-mediated interference with insulin signaling pathways (e.g. serine phosphorylation of IRS-1). | Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia. |

| Vascular Complications | Impaired nitric oxide synthesis; increased expression of adhesion molecules on endothelium. | Endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. |

Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Implications of Androgen Deficiency

The brain is a profoundly steroid-sensitive organ. Androgen and estrogen receptors are widely distributed in areas critical for cognition, mood, and memory, including the hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebral cortex. Testosterone and its metabolites, estradiol and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), exert powerful neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects. The long-term absence of these hormones, as seen in chronic hypogonadism, can render the brain more vulnerable to age-related decline and neurodegenerative processes.

What Is the Role of Androgens in Brain Health?

Testosterone’s influence on the brain is multifaceted. It has been shown to:

- Promote Neuronal Survival ∞ Androgens can protect neurons from apoptosis (programmed cell death) induced by various insults, including oxidative stress and beta-amyloid toxicity, a key pathological feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Enhance Synaptic Plasticity ∞ Testosterone and estradiol are known to modulate synaptic structure and function, which is the cellular basis of learning and memory. They can increase dendritic spine density and promote the formation of new synaptic connections.

- Modulate Neurotransmitters ∞ Sex steroids can influence the synthesis and activity of key neurotransmitter systems, including the cholinergic, serotonergic, and dopaminergic systems, which are all implicated in mood and cognitive function.

- Reduce Neuroinflammation ∞ Testosterone has anti-inflammatory properties within the central nervous system. It can suppress the activation of microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, and reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines within brain tissue.

In the context of hypogonadism, the loss of these protective mechanisms can lead to a state of heightened neuroinflammation and impaired neuronal function. This may manifest clinically as deficits in specific cognitive domains, such as processing speed, working memory, and executive function.

The common complaints of “brain fog,” difficulty concentrating, and low motivation in hypogonadal men are likely the subjective experience of this underlying neurophysiological disruption. While research is ongoing, there is a compelling hypothesis that long-term, untreated hypogonadism could be a significant, modifiable risk factor for accelerated cognitive decline and an increased risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases in later life.

The decision to initiate a hormonal optimization protocol, therefore, is not simply about alleviating symptoms like low libido or fatigue. From an academic perspective, it is a preventative strategy aimed at correcting a fundamental state of metabolic and neurological vulnerability. By restoring physiological androgen levels, the goal is to interrupt the vicious cycles of inflammation and insulin resistance, thereby preserving long-term cardiovascular, metabolic, and cognitive health.

References

- Bhasin, S. et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715 ∞ 1744.

- Grossmann, M. and B. B. Yeap. “Testosterone and the Cardiovascular System.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 10, 2015, pp. 3706-3718.

- Saad, F. et al. “Testosterone as a potential effective therapy in treatment of obesity in men with testosterone deficiency ∞ a review.” Current Diabetes Reviews, vol. 8, no. 2, 2012, pp. 131-143.

- Jones, T. H. “Testosterone deficiency ∞ a risk factor for cardiovascular disease?” Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 21, no. 8, 2010, pp. 496-503.

- Rochira, V. et al. “The complications of male hypogonadism ∞ is it just a matter of low testosterone?” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 46, no. 11, 2023, pp. 2297-2308.

- Salonia, A. et al. “Male hypogonadism ∞ a clinical guide.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 15, no. 9, 2019, pp. 503-520.

- Jockenhovel, F. “Testosterone therapy–what, when and to whom?” The Aging Male, vol. 7, no. 4, 2004, pp. 319-324.

- Al-Zoubi, R. M. et al. “The role of testosterone in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease.” Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation, vol. 42, no. 3, 2021, pp. 233-242.

- Behre, H. M. et al. “EAU Guidelines on Male Hypogonadism.” European Association of Urology, 2022.

- Janse, F. et al. “Testosterone concentrations, using a direct automated immunoassay, in labs, and mortality in men ∞ The Tromsø Study.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 95, no. 9, 2010, pp. 4364-4372.

Reflection

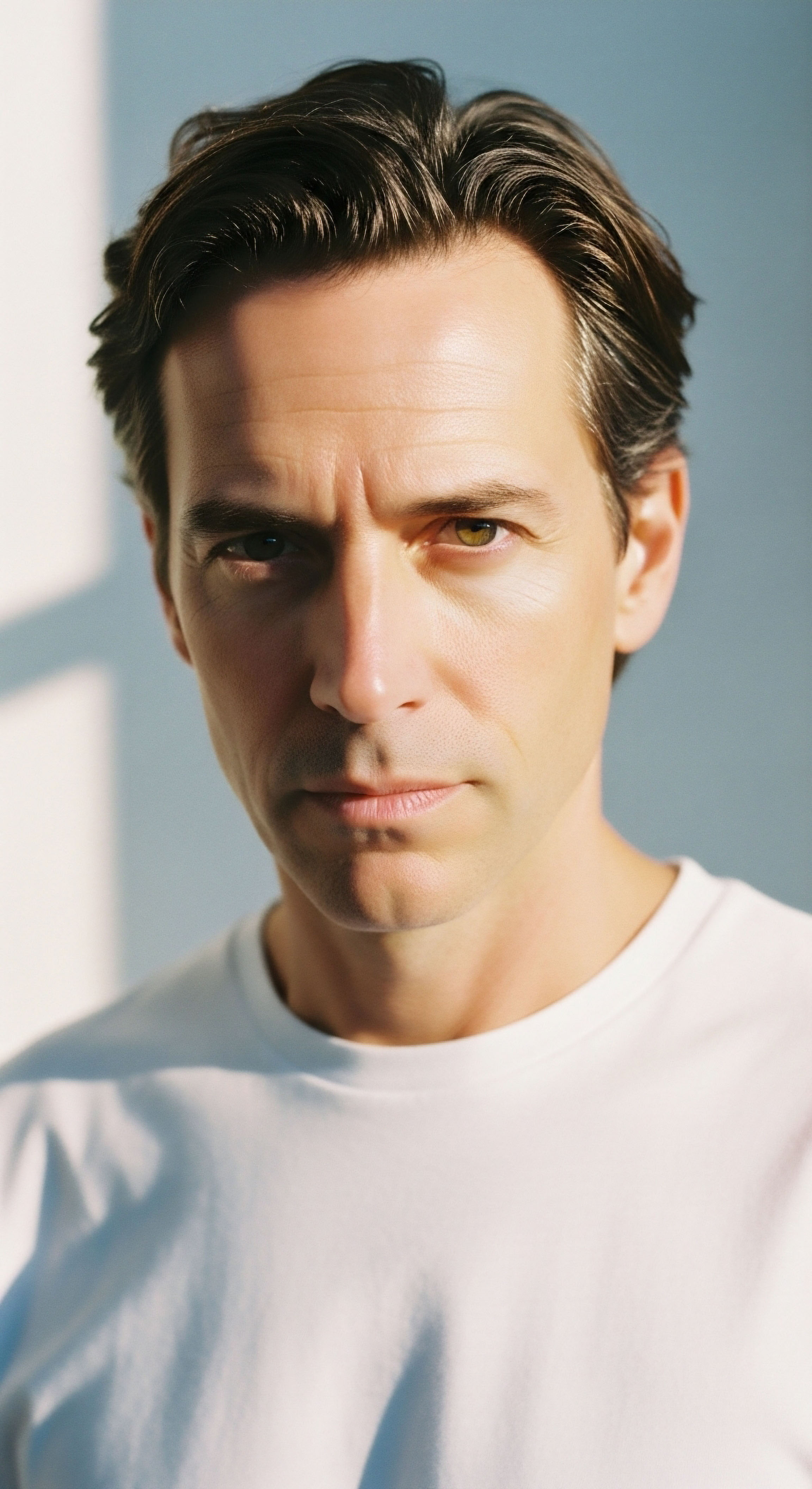

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory, connecting a physical sign to its systemic roots and potential clinical pathways. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive concern to one of active understanding.

Your body’s signals are not arbitrary; they are a sophisticated form of communication about its internal state. The journey through this information is intended to equip you with a new lens through which to view your own health, translating complex science into personal insight.

This understanding forms the foundation for a more meaningful conversation with a clinical expert. Every individual’s biology is unique, shaped by a lifetime of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. A truly effective path forward is one that is built upon this personal context, using objective data and clinical expertise to design a protocol tailored specifically to your body’s needs.

The ultimate goal is the restoration of function and the optimization of your health, allowing you to reclaim a state of vitality that is grounded in biological balance. Consider this knowledge the beginning of a new, more informed chapter in your personal health narrative.