Fundamentals

The decision to begin a journey of hormonal optimization is deeply personal, often born from a collection of subtle yet persistent feelings. It could be a pervasive fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a quiet decline in vitality, or a sense that your body’s internal calibration is misaligned.

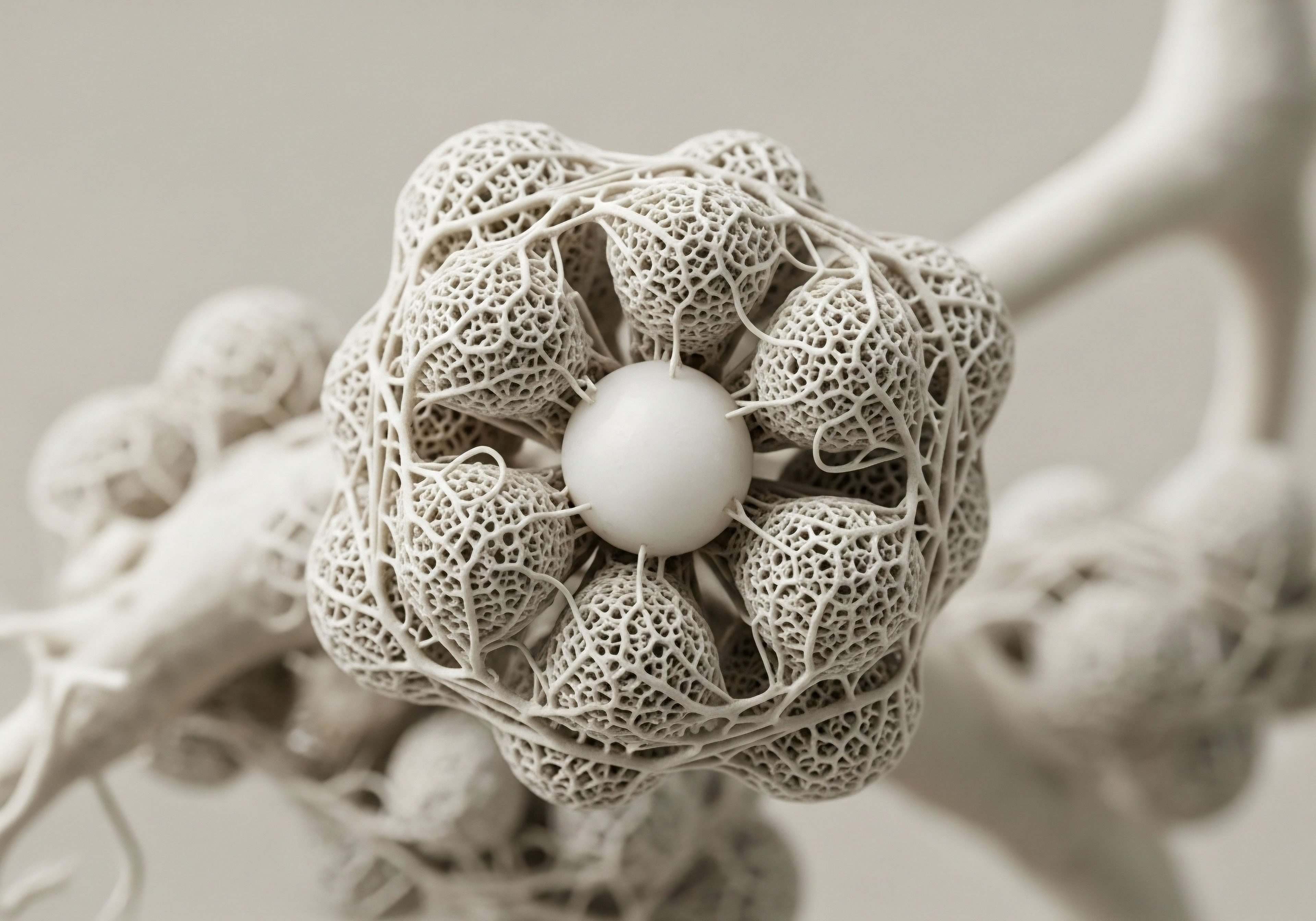

These experiences are valid and real. They are signals from your biology, communications from a complex internal system that is asking for attention. Understanding this system is the first step toward reclaiming your functional well-being. At the very center of male hormonal health lies a sophisticated communication network known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is the body’s internal command structure for hormone production.

Imagine the HPG axis as a finely tuned thermostat system for your hormones. The hypothalamus, a small region in your brain, acts as the control center. It senses when your body’s testosterone levels are low and sends out a chemical message called Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

This message travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the master gland of the body. In response to GnRH, the pituitary releases two other crucial hormones into the bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones then travel down to the testes, the gonads, with specific instructions.

LH tells the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone. FSH, on the other hand, is primarily responsible for stimulating the Sertoli cells to support sperm production. This entire sequence is designed to maintain hormonal equilibrium.

The HPG axis functions as a self-regulating feedback loop, where the brain directs testosterone production and the resulting hormone levels signal back to the brain to modulate this production.

The system completes its circuit through a process called negative feedback. Once testosterone is produced and circulating in the bloodstream, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland detect its presence. When levels are sufficient, they reduce their output of GnRH and LH, respectively. This elegant mechanism prevents overproduction and keeps the system in balance.

When you introduce testosterone from an external source, as in Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), your body receives the hormone it needs to alleviate symptoms of low testosterone. Your brain, however, perceives these high, stable levels of circulating testosterone and concludes that its job is done.

It no longer senses a need to send the signals to produce its own. Consequently, the hypothalamus reduces or stops releasing GnRH, which in turn causes the pituitary to stop releasing LH and FSH. This deliberate, predictable shutdown of the internal production signal is what is known as HPG axis suppression.

The Immediate Biological Response to Suppression

When the HPG axis is suppressed, the communication from the brain to the testes goes quiet. The primary and most immediate consequence of this silence is a change in the function and size of the testes. Since LH is no longer signaling the Leydig cells to produce testosterone, they become dormant.

Because the testes are the primary site of this production, this internal manufacturing process halts. Simultaneously, the reduction in FSH signaling to the Sertoli cells leads to a significant decline in spermatogenesis, the process of sperm production. This can result in reduced fertility or even temporary infertility, a state known as azoospermia, where no sperm is present in the ejaculate. For many individuals, this is a primary and significant consideration when contemplating hormonal optimization protocols.

Another physical manifestation of HPG axis suppression is testicular atrophy, or a reduction in the size of the testes. The testes are composed of tissues that are metabolically active and dependent on the constant signaling from the pituitary. When LH and FSH are absent, these tissues are no longer stimulated.

This leads to a decrease in their volume. This change is a direct structural consequence of the functional dormancy induced by TRT. It is a predictable outcome of suppressing the natural signaling pathway. Understanding this mechanism is foundational to appreciating why certain adjunctive therapies are often included in a comprehensive treatment plan, as they are designed to address these very effects.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of HPG axis suppression reveals a more detailed landscape of physiological changes. The implications extend past the simple cessation of endogenous testosterone production. When the testes become dormant due to the absence of LH and FSH signaling, it is not just testosterone synthesis that is affected.

The testes are complex endocrine organs responsible for producing a wide array of androgens and other hormonal precursors that contribute to the body’s overall biochemical environment. The suppression of this local manufacturing plant has nuanced, systemic consequences.

One of the most critical aspects to consider is the difference between intratesticular testosterone (ITT) and serum testosterone. While TRT effectively elevates serum testosterone levels, alleviating symptoms like fatigue and low libido, it simultaneously causes ITT levels to plummet.

Endogenous testosterone production results in extremely high concentrations of testosterone within the testes, estimated to be 100-fold higher than in the bloodstream. This high ITT environment is absolutely essential for spermatogenesis. The elevated serum testosterone from an injection cannot replicate this localized concentration. This explains why TRT alone, without supportive therapies, consistently impairs fertility. The Sertoli cells, which nurture developing sperm, require this potent local hormonal milieu to function correctly. Without it, sperm maturation halts.

Strategies for Mitigating HPG Axis Suppression

Recognizing the functional consequences of HPG axis suppression has led to the development of more sophisticated clinical protocols. These strategies are designed to allow an individual to benefit from therapeutic testosterone levels while preserving testicular function and fertility potential. The goal is to provide an external signal that mimics the body’s natural pituitary hormones, keeping the testes active even while the brain’s own signals are suppressed.

Common Adjunctive Therapies

- Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) and Gonadorelin ∞ Historically, hCG has been a cornerstone of preserving testicular function during TRT. hCG is a hormone that mimics Luteinizing Hormone (LH). By binding to the LH receptors on the Leydig cells, it directly stimulates them to produce testosterone and maintain their size and function. This keeps ITT levels high, thereby supporting spermatogenesis. More recently, Gonadorelin, a synthetic form of GnRH, has been used. It works by stimulating the pituitary to release its own LH and FSH. It is administered in a pulsatile fashion to mimic the body’s natural GnRH rhythm, which can help maintain the entire HPG axis signaling pathway to some degree.

- Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) ∞ Compounds like Clomiphene Citrate (Clomid) and Enclomiphene work differently. They act at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary. SERMs selectively block estrogen receptors in the brain. Since estrogen also provides negative feedback to the HPG axis, blocking its effect tricks the brain into thinking estrogen levels are low. This prompts the pituitary to increase its output of LH and FSH, which in turn stimulates the testes. Enclomiphene is often preferred as it is the pure, active isomer that stimulates gonadotropins with fewer side effects than Clomiphene.

- Aromatase Inhibitors (AIs) ∞ Medications like Anastrozole are used to control the conversion of testosterone to estradiol. While not directly supporting the HPG axis, their use is interconnected. Elevated estradiol levels can strengthen the negative feedback signal to the hypothalamus, further suppressing the axis. By managing estradiol, AIs can help maintain a more balanced hormonal profile and prevent side effects associated with excess estrogen.

Modern TRT protocols often integrate compounds like Gonadorelin or SERMs to maintain testicular function, transforming the therapy from simple replacement to a more holistic system management.

The choice of protocol depends heavily on the individual’s goals. For a man who prioritizes fertility, a combination of TRT with Gonadorelin or a standalone therapy with Enclomiphene might be the most appropriate path. For an older individual where fertility is not a concern, TRT alone might be sufficient. The table below outlines a comparison of common approaches.

| Protocol | Mechanism of Action | Effect on HPG Axis | Impact on Testicular Function | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRT Monotherapy | Provides exogenous testosterone, increasing serum levels. | Suppresses GnRH, LH, and FSH via negative feedback. | Reduces testicular size and halts spermatogenesis. | Symptom management in men where fertility is not a concern. |

| TRT + Gonadorelin | Exogenous testosterone for symptoms; Gonadorelin stimulates the pituitary to produce LH/FSH. | Brain’s axis is suppressed, but pituitary is stimulated. | Maintains testicular size and intratesticular testosterone, preserving fertility. | Comprehensive symptom management while maintaining fertility. |

| Enclomiphene Monotherapy | Blocks estrogen receptors in the brain, increasing natural LH/FSH production. | Stimulates the entire HPG axis to produce more endogenous testosterone. | Enhances natural testicular function and increases testicular volume. | Men with secondary hypogonadism who wish to avoid exogenous hormones and preserve fertility. |

What Are the Broader Systemic Implications?

The conversation around HPG axis suppression is evolving to include its effects on systems beyond reproduction. The testes do more than produce testosterone and sperm. They synthesize other important hormones, including DHEA and pregnenolone, often referred to as neurosteroids because of their significant role in the brain.

These hormones are crucial for mood regulation, cognitive function, and feelings of well-being. Standard TRT protocols effectively replace testosterone but do not replicate the full suite of hormones produced by fully active testes. A suppressed HPG axis means the natural, pulsatile release of gonadotropins and the subsequent cascade of testicular hormone production is replaced by a more static, external supply.

The long-term consequences of altering this intricate hormonal symphony are an active area of clinical investigation, particularly concerning their potential impact on neurological health and metabolic function over many years.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of long-term Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis suppression transcends the well-documented effects on fertility and testicular volume. The academic inquiry shifts toward the second- and third-order consequences of silencing the endogenous pulsatile signaling of gonadotropins.

The core of this advanced perspective lies in understanding that Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) are not merely gonadal messengers. These complex glycoproteins have receptors and exert biological effects in a variety of extragonadal tissues. The chronic absence of their pulsatile signaling, a state induced by conventional Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), may have subtle but clinically significant systemic implications over the course of decades.

Extragonadal Actions of Gonadotropins

While the testes are the primary target of LH and FSH, functional receptors for these hormones have been identified in numerous other tissues, including the brain, adrenal glands, thyroid, bone, and vascular endothelium. The physiological role of these extragonadal receptors is an area of intense research.

For instance, LH receptors in the brain, particularly in the hippocampus, suggest a direct role for LH in cognitive processes and neurogenesis. Some evidence indicates that the supraphysiological, non-pulsatile LH levels seen in certain pathological states can be detrimental.

Conversely, the complete long-term absence of LH signaling that occurs with HPG suppression on TRT may also represent a departure from optimal physiological functioning. The natural, rhythmic pulses of LH are a form of biological information. Replacing this dynamic signal with a state of chronic absence could alter the cellular environment in these non-target tissues over time.

The implications for neuroendocrine health are particularly compelling. The testes are a source of neuroactive steroids like pregnenolone and DHEA, whose synthesis is influenced by the gonadotropic milieu. While TRT normalizes serum testosterone, it does not restore the endogenous production of these other steroids.

Pregnenolone is a key precursor to all steroid hormones and also functions as a potent signaling molecule in the central nervous system, modulating NMDA and GABA receptor activity, which are fundamental to learning, memory, and mood. Long-term HPG suppression effectively outsources steroidogenesis to a pharmaceutical preparation, bypassing the nuanced, multi-hormone synthesis that occurs in healthy, stimulated gonads.

This raises questions about whether TRT alone can fully replicate the neuroprotective and mood-stabilizing benefits of a fully functional HPG axis.

The long-term suppression of the HPG axis represents a shift from a dynamic, pulsatile endocrine system to a static hormonal state, the full systemic consequences of which are still being elucidated.

Metabolic and Cardiovascular Considerations

The endocrine system is deeply interwoven with metabolic regulation. The chronic suppression of the HPG axis may have long-term metabolic consequences that are not immediately apparent. For example, FSH receptors have been found on adipocytes (fat cells) and in arterial walls. Research suggests FSH may play a role in regulating body composition and lipid metabolism.

Some studies in post-menopausal women have linked higher FSH levels to increased abdominal adiposity and unfavorable metabolic profiles. While the context is different in men on TRT (where FSH is suppressed, not elevated), it highlights that FSH has metabolic bioactivity. Silencing this signal for years or decades could contribute to long-term changes in fat distribution, insulin sensitivity, and cardiovascular health that are independent of serum testosterone levels alone.

The table below details some of the advanced concepts related to the potential long-term effects of altering the native hormonal milieu through HPG axis suppression.

| Biological System | Conventional View of TRT Effect | Advanced Consideration of HPG Suppression | Potential Long-Term Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Nervous System | Restores testosterone, improving mood, libido, and cognition. | Eliminates pulsatile LH signaling and reduces endogenous neurosteroid (Pregnenolone, DHEA) production. | Subtle alterations in cognitive function, mood stability, or neuro-inflammation over decades. |

| Metabolic Health | Improves body composition and insulin sensitivity via testosterone restoration. | Abolishes FSH signaling, which may have direct effects on adipocytes and lipid metabolism. | Potential long-term changes in fat metabolism and distribution independent of testosterone’s effects. |

| Skeletal System | Maintains bone mineral density through adequate androgen and estrogen levels. | LH and FSH receptors are present on osteoblasts and osteoclasts, suggesting a direct role in bone remodeling. | The absence of direct gonadotropin signaling could represent a loss of one pathway supporting bone health. |

| Cardiovascular System | Positive effects on lean mass and lipids, but concerns about erythrocytosis and potential events. | FSH and LH receptors on vascular endothelium may influence vascular tone and inflammatory processes. | Alteration of local vascular regulation, potentially affecting long-term cardiovascular risk profile. |

How Does HPG Axis Recovery Vary after Long Term Suppression?

A critical academic and clinical question is the capacity of the HPG axis to recover after prolonged periods of suppression. Recovery is highly variable and depends on several factors, including the duration of therapy, the age of the individual, and their baseline gonadal function before starting TRT.

For some, cessation of TRT can lead to a relatively swift return of GnRH, LH, and FSH signaling, with endogenous testosterone production resuming within months. For others, particularly those on therapy for many years, the recovery can be sluggish or incomplete. This state is sometimes referred to as persistent secondary hypogonadism.

The underlying mechanism may involve a desensitization of the GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus or a reduced functional capacity of the pituitary gonadotrophs after a long period of inactivity. From a clinical standpoint, this underscores the importance of informed consent, ensuring individuals understand that TRT may be a lifelong commitment, as a return to baseline function is not guaranteed.

Protocols for discontinuing TRT, often called “Post-TRT” or “Fertility-Stimulating” protocols, utilize medications like Tamoxifen, Clomid, or Enclomiphene, sometimes in combination with Gonadorelin. These protocols are designed to actively stimulate the dormant axis at multiple levels. The use of SERMs aims to reinvigorate hypothalamic and pituitary activity, while Gonadorelin provides a direct stimulus to the testes.

The success of these restart protocols provides further evidence of the plasticity of the HPG axis, while also highlighting that its dormancy is a significant physiological state that often requires active intervention to reverse.

References

- Ramasamy, Ranjith, et al. “Testosterone Supplementation Versus Clomiphene Citrate for Hypogonadism ∞ A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The Journal of Urology, vol. 191, no. 4, 2014, pp. 1073-1079.

- Bhasin, Shalender, et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715-1744.

- Weinbauer, G. F. et al. “Intratesticular Testosterone and Spermatogenesis.” Acta Endocrinologica Supplementum, vol. 271, 1985, pp. 69-78.

- Zitzmann, Michael, and Eberhard Nieschlag. “Testosterone levels in healthy men and the relation to bone mass and fat mass.” European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 143, no. 4, 2000, pp. 477-485.

- Walther, Andreas, et al. “The role of testosterone, the androgen receptor, and hypothalamic-pituitary ∞ gonadal axis in depression in ageing Men.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 24, no. 1, 2019, pp. 114-130.

- Rastrelli, Giulia, et al. “Testosterone Treatment for Men with Late-Onset Hypogonadism ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 104, no. 10, 2019, pp. 4405-4422.

- Cowen, P. J. “Neuroendocrine and neurochemical processes in depression.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 21, no. 2, 1997, pp. 137-141.

- Hohl, Alexandre, et al. “Testosterone and the Heart ∞ A Comprehensive Review.” Journal of the American Heart Association, vol. 6, no. 9, 2017, e005824.

- Finkelstein, Joel S. et al. “Gonadal Steroids and Body Composition, Strength, and Sexual Function in Men.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 369, no. 11, 2013, pp. 1011-1022.

- Kalyani, Rita R. et al. “Association of Testosterone and Sex Hormone ∞ Binding Globulin with Men’s Health-Related Quality of Life in the Testosterone Trials.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 102, no. 4, 2017, pp. 1161-1169.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map of a complex biological territory. It details the known pathways, the predictable consequences, and the frontiers of our current clinical understanding. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose ∞ to transform abstract symptoms into understandable mechanisms and to illuminate the logic behind different therapeutic strategies.

Your own health story is unique, written in the language of your specific biology and personal experience. The path toward vitality is one of partnership ∞ between you and a knowledgeable clinician who can help interpret your body’s signals.

Your Internal Dialogue

Consider the initial feelings that prompted your search for answers. Was it a lack of energy, a change in mood, or a desire to function at a higher capacity? Now, view those feelings through the lens of this intricate hormonal communication system. The journey of hormonal optimization is a process of recalibration.

It involves listening to your body with a new level of understanding and making informed choices that align with your long-term vision for your health. The ultimate goal is not just the alleviation of symptoms, but the restoration of a robust, resilient internal system that allows you to operate with full vitality.