Fundamentals

Your body’s internal communication network relies on chemical messengers, a system of profound elegance and precision. When you experience symptoms like persistent fatigue, a shift in mood that feels disconnected from your daily life, or changes in your physical vitality, it often points to a disruption in this delicate biochemical conversation.

The liver, your master metabolic organ, is a central hub in this communication network. It is profoundly responsive to the messages sent by sex steroids like testosterone and estrogen. Understanding the long-term relationship between these hormonal signals and your liver’s health is the first step toward recalibrating your body’s internal ecosystem and reclaiming your functional wellbeing.

The conversation between sex steroids and the liver is constant and deeply influential. Estrogen, for instance, plays a significant role in maintaining the liver’s metabolic balance. In women, the natural decline of estrogen during the perimenopausal and postmenopausal phases is directly associated with an increased incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

This condition, characterized by the accumulation of fat in liver cells, is a physical manifestation of a deeper metabolic dysregulation. The protective qualities of estrogen help regulate lipid metabolism and reduce inflammation within the liver, and its decline removes a key layer of this defense.

The liver is a primary recipient of hormonal signals, and its health is intrinsically linked to the balance of sex steroids.

Similarly, testosterone levels are a critical indicator of metabolic health, particularly in men. Low testosterone is a well-established marker for an increased risk of NAFLD and broader metabolic syndrome. The hormone directly influences how the body manages insulin, processes lipids, and controls inflammation.

When testosterone levels are suboptimal, the liver’s ability to perform these functions efficiently is compromised, leading to the gradual buildup of fat and a cascade of related health issues. This is a clear physiological signal that the body’s metabolic machinery is under strain. The modulation of these hormones through carefully managed clinical protocols is designed to restore this essential biochemical dialogue, supporting the liver’s function and, by extension, the health of the entire system.

The Liver as a Hormonally Responsive Organ

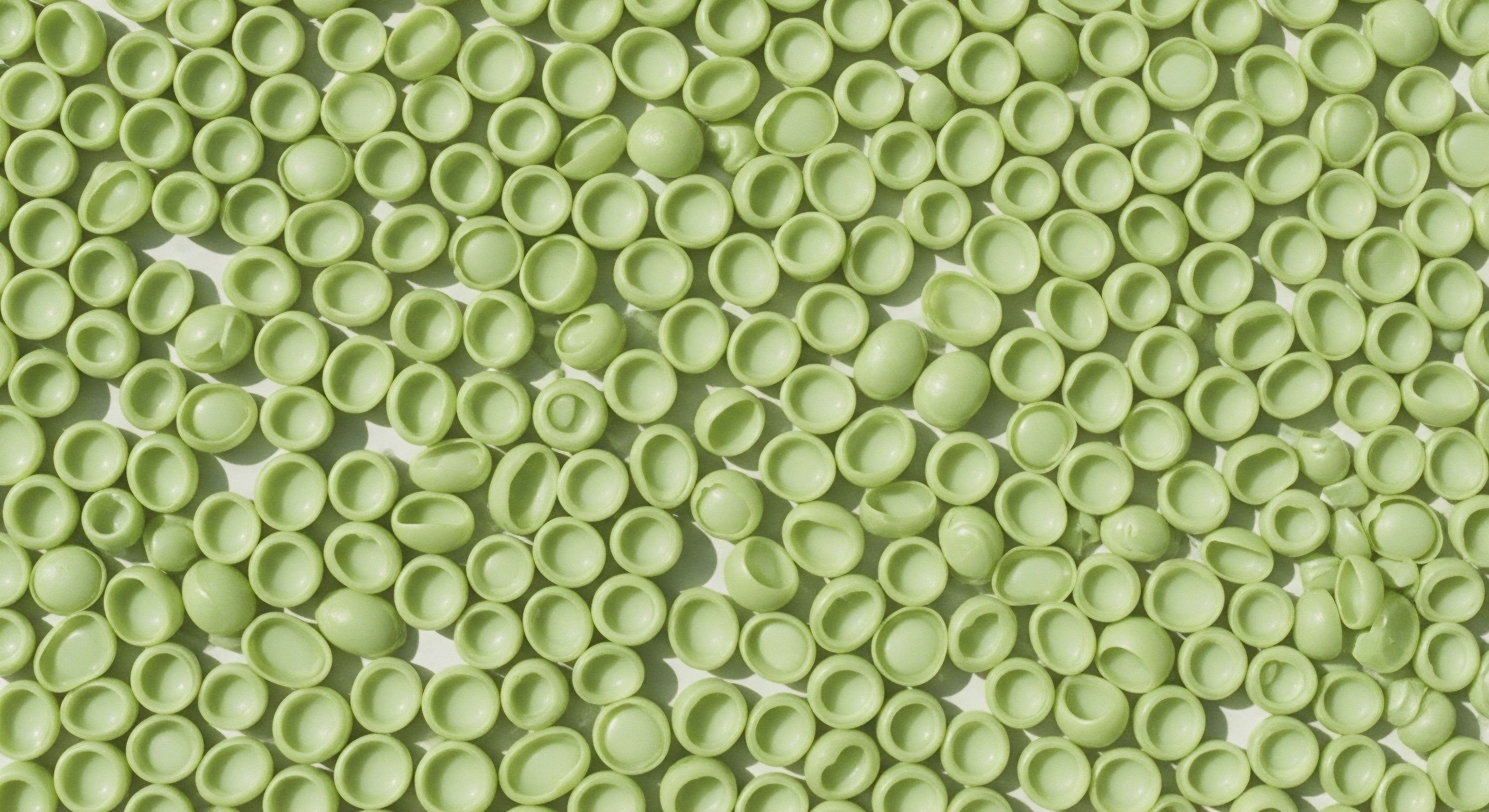

To fully appreciate the connection, it is useful to visualize the liver not as a passive filter but as an active, intelligent organ equipped with specific receptors for hormones. These receptors, known as androgen receptors (AR) and estrogen receptors (ER), function like docking stations.

When testosterone or estrogen binds to its respective receptor, it initiates a cascade of genetic instructions inside the liver cells. These instructions dictate how the liver should manage fats, sugars, and proteins. Therefore, the health of your liver is directly tied to the clarity and consistency of these hormonal signals. A disruption in hormone levels sends confusing or incomplete messages, leading to metabolic errors that can manifest as fatty liver disease over time.

How Do Hormones Influence Liver Fat?

The influence of sex steroids on liver fat accumulation is a primary concern in long-term health. Estrogen tends to have an anti-steatotic effect, meaning it helps prevent the buildup of fat in hepatocytes (liver cells). It achieves this by regulating the genes involved in lipid synthesis and breakdown.

Conversely, an imbalance ∞ either low testosterone in men or elevated androgens in women ∞ can promote the storage of triglycerides in the liver. This process is a central feature of NAFLD, which progresses from simple fat accumulation (steatosis) to inflammation (steatohepatitis, or NASH), and potentially to more serious conditions like fibrosis and cirrhosis. Hormonal optimization protocols aim to correct these imbalances, thereby restoring the liver’s natural ability to manage lipids effectively and preventing the progression of this metabolic disease.

Intermediate

Understanding the physiological relationship between sex steroids and the liver provides the foundation for clinical intervention. When we design personalized wellness protocols, the objective is to restore the body’s hormonal signaling to a state of optimal function.

This biochemical recalibration has profound and direct effects on liver health, particularly by addressing the metabolic dysfunctions that underpin conditions like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The choice of hormone, the dosage, and especially the route of administration are all critical variables that determine the long-term hepatic implications. Each element is selected to work in concert with your body’s innate biological pathways, supporting the liver’s metabolic integrity.

For men with clinically diagnosed hypogonadism, testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) represents a powerful tool for metabolic restoration. Long-term prospective studies have demonstrated that TRT in this population leads to significant improvements in liver health. Specifically, these studies show a marked decrease in the Fatty Liver Index (FLI), a reliable marker for hepatic steatosis.

This improvement is accompanied by reductions in key liver enzymes like gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and improvements in lipid profiles, including a decrease in triglycerides. The mechanism behind this is multifaceted; restoring testosterone levels improves insulin sensitivity, reduces visceral fat, and decreases systemic inflammation, all of which lessens the metabolic burden on the liver.

The data suggests that for hypogonadal men, properly managed TRT is not a risk to the liver but a therapeutic intervention that can reverse the progression of fatty liver disease.

Route of Administration Why It Matters

The method by which hormones are introduced into the body is a determining factor in their effect on the liver. Oral hormones are processed through the gastrointestinal tract and undergo a “first-pass metabolism” in the liver before entering systemic circulation. This initial pass can place a significant metabolic load on the liver, altering the production of lipids and clotting factors. This is particularly true for certain synthetic oral androgens.

Injectable and transdermal delivery systems, such as testosterone cypionate injections or topical estrogen gels, bypass this first-pass metabolism. By entering the bloodstream directly, they mimic the body’s natural release of hormones more closely and avoid placing undue stress on the liver. This distinction is critical for long-term safety and efficacy.

- Oral Administration ∞ Hormones are absorbed and sent directly to the liver. This route is associated with a higher risk of altering liver enzyme levels and lipid profiles. The 17-alpha alkylated modification made to many oral anabolic steroids to prevent their breakdown is what makes them particularly hepatotoxic.

- Transdermal Administration ∞ Gels, creams, or patches deliver hormones through the skin directly into the bloodstream. A study comparing oral and transdermal estrogen found that transdermal delivery was more beneficial in preventing the progression of NAFLD.

- Intramuscular/Subcutaneous Injections ∞ This method also delivers hormones directly into circulation, avoiding the first-pass effect. Long-term studies showing the benefits of TRT on liver function have often used injectable forms like testosterone undecanoate.

Hormonal Protocols for Women and Liver Health

For women, hormonal therapy during the menopausal transition also has significant implications for liver health. The decline in estrogen is a known risk factor for the development and progression of NAFLD. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) that restores estrogen levels can be protective. Studies indicate that postmenopausal women undergoing HRT show a reduced incidence of NAFLD.

The choice of delivery method is again important. Transdermal estrogen has been shown to be more beneficial than oral estrogen for preventing NAFLD progression, as it has a less pronounced effect on triglyceride levels.

The addition of testosterone in low doses for women, a practice aimed at improving libido, energy, and bone density, must also be considered. While large-scale, long-term data on the hepatic effects of TRT in women is less abundant than for men, the principles of avoiding oral administration and using physiologically appropriate doses are paramount to ensure liver safety. The goal is to restore balance without overburdening the body’s metabolic systems.

| Administration Route | First-Pass Metabolism | Effect on Triglycerides | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Yes | Can Increase | Certain Synthetic Steroids, HRT Formulations |

| Transdermal | No | Neutral/Beneficial | Estrogen Gels/Patches, Testosterone Creams |

| Injectable | No | Neutral/Beneficial | Testosterone Cypionate/Undecanoate |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of sex steroid modulation on hepatic function requires moving beyond general metabolic effects to the specific molecular and cellular mechanisms at play. The liver is not merely a target of hormonal action but an active participant in steroid metabolism and signaling.

The long-term implications of hormonal interventions are dictated by a complex interplay between the specific steroid administered, its interaction with hepatic nuclear receptors, the subsequent genomic and non-genomic signaling cascades, and the method of delivery, which determines the steroid’s initial metabolic fate. A central distinction must be made between physiologic hormone replacement and supraphysiologic anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) use, as their effects on the liver are profoundly different.

Physiologic testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men has been shown to improve hepatic steatosis, a finding that contrasts sharply with the known hepatotoxicity of supraphysiologic, chemically modified androgens.

Medically supervised testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) in men with confirmed hypogonadism aims to restore serum testosterone to a normal physiologic range. In this context, long-term prospective registry studies have consistently documented improvements in liver function. These benefits are mediated by testosterone’s action on hepatic androgen receptors, which improves insulin signaling, upregulates lipid oxidation pathways, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects.

This ameliorates the core drivers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and can lead to a reversal of hepatic steatosis and a reduction in fibrosis risk. The use of parenteral testosterone formulations, such as testosterone undecanoate or cypionate, is key to these positive outcomes, as they avoid the first-pass hepatic metabolism that can induce adverse lipid changes.

What Is the Pathophysiology of Androgen-Induced Hepatotoxicity?

The hepatotoxicity widely associated with “steroids” originates almost exclusively from the use of a specific class of synthetic derivatives ∞ 17-alpha alkylated (17α-AA) anabolic-androgenic steroids. This chemical modification was designed to reduce hepatic breakdown and permit oral administration, but it is the very source of their potential for liver damage. The pathophysiology of 17α-AA steroid-induced liver injury is distinct and multifaceted:

- Intrahepatic Cholestasis ∞ 17α-AA steroids can impair the function of bile salt export pumps in the canalicular membrane of hepatocytes. This disruption of bile flow leads to a “bland cholestasis,” characterized by jaundice and elevated bilirubin with only mild elevations in aminotransferases. It is a direct toxic effect on the bile secretory machinery of the liver cell.

- Peliosis Hepatis ∞ This is a rare and serious vascular condition characterized by the formation of blood-filled cysts within the liver. It is strongly associated with long-term use of 17α-AA steroids and is thought to result from damage to the sinusoidal endothelial cells, leading to sinusoidal dilation and the formation of these cavities.

- Hepatic Neoplasms ∞ Prolonged exposure to high doses of 17α-AA steroids is linked to the development of hepatic adenomas and, in some cases, hepatocellular carcinoma. These tumors often regress upon cessation of the offending agent, highlighting the direct causative role of the drug.

These severe outcomes are almost exclusively confined to the context of supraphysiologic dosing of these orally active, modified androgens. They are not characteristic features of physiologic testosterone replacement with unmodified, injectable testosterone. This distinction is of the utmost clinical importance.

How Does Estrogen Signaling Modulate Hepatic Fibrosis?

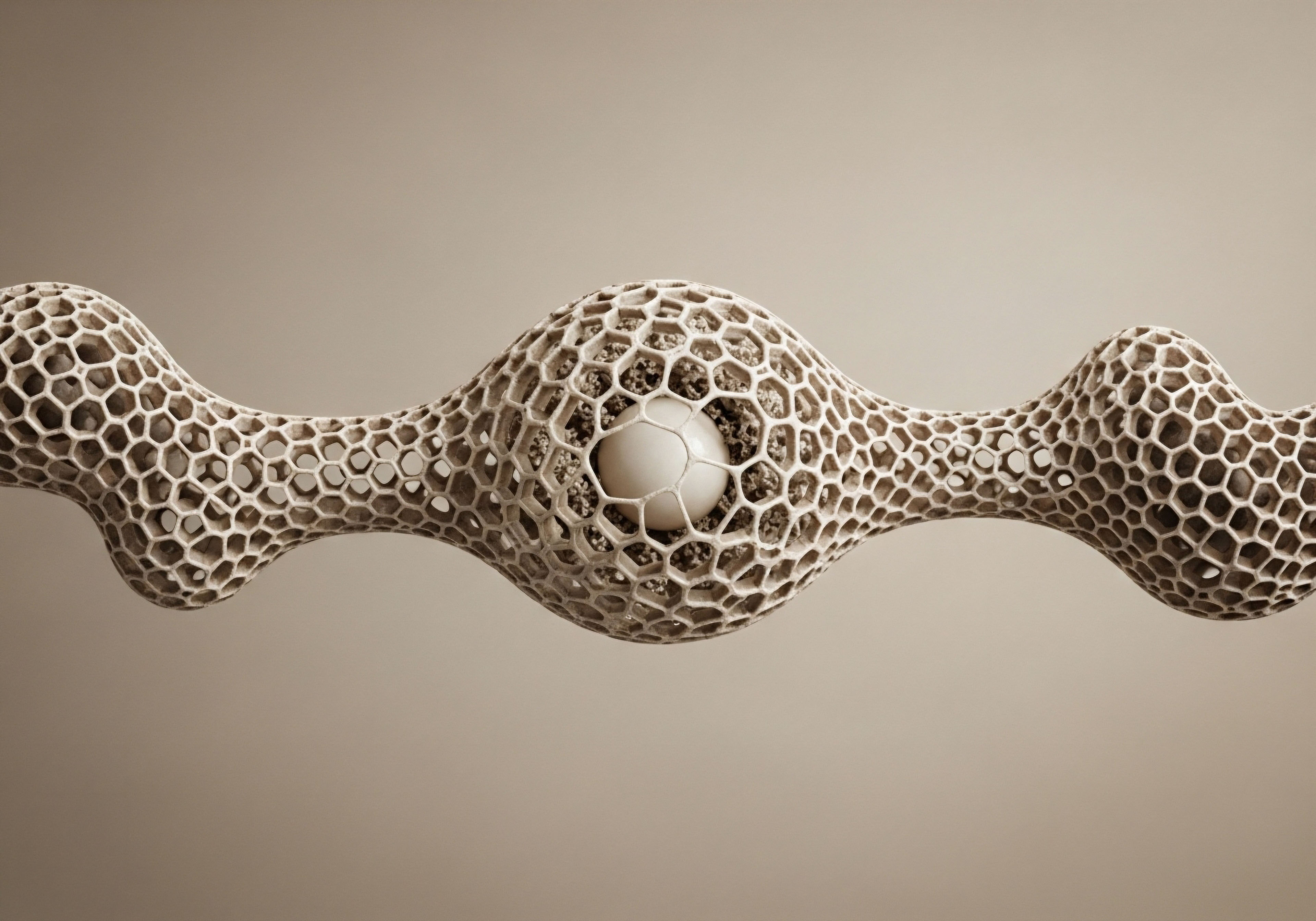

Estrogen signaling within the liver provides a powerful protective effect against the progression of liver disease, particularly fibrosis. The primary estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2), exerts its effects mainly through estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), which is expressed in multiple liver cell types, including hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).

HSCs are the primary cell type responsible for producing the extracellular matrix proteins that form scar tissue in the liver. In a healthy liver, HSCs are in a quiescent state. Upon liver injury, they become activated, proliferate, and begin to secrete large amounts of collagen.

E2, acting through ERα, has been shown to directly inhibit the activation of HSCs. This anti-fibrotic action helps explain why premenopausal women have a lower incidence and severity of liver fibrosis compared to men and postmenopausal women.

The loss of this protective E2 signaling after menopause is a key factor in the accelerated progression of liver disease observed in this population. Consequently, menopausal hormone therapy, particularly with transdermal estrogen, may offer a therapeutic strategy to mitigate fibrosis risk by restoring this protective signaling pathway.

| Steroid Type | Chemical Structure | Primary Use | Risk of Cholestasis | Risk of Peliosis Hepatis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone Esters (e.g. Cypionate) | Unmodified (Parenteral) | Medical TRT | Very Low | Extremely Low |

| 17α-Alkylated AAS (e.g. Stanozolol) | Modified (Oral) | AAS Abuse | High | Moderate to High |

References

- Al-Qudimat, Ahmad, et al. “Testosterone treatment improves liver function and reduces cardiovascular risk ∞ A long-term prospective study.” Arab Journal of Urology, vol. 19, no. 3, 2021, pp. 376-386.

- Choi, D. H. et al. “Different effects of menopausal hormone therapy on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease based on the route of estrogen administration.” Scientific Reports, vol. 13, no. 1, 2023, p. 15538.

- LiverTox ∞ Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. “Androgenic Steroids.” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2020.

- Nseir, William, and Nagib Shalhub. “The effect of testosterone therapy on liver function and steatosis in men with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 36, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-2.

- Kasarinaite, L. et al. “The Influence of Sex Hormones in Liver Function and Disease.” Cells, vol. 12, no. 12, 2023, p. 1604.

- Ress, C. and H. Kaser. “Hepatotoxicity of anabolic androgenic steroids.” Liver International, vol. 36, no. 5, 2016, pp. 671-672.

- Yassin, A. A. et al. “Long-term testosterone therapy improves liver parameters and steatosis in hypogonadal men ∞ a prospective controlled registry study.” Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 14, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1-9.

- Stanworth, R. D. and T. H. Jones. “Testosterone for the aging male ∞ current evidence and recommended practice.” Clinical Interventions in Aging, vol. 3, no. 1, 2008, pp. 25-44.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the intricate biological landscape connecting your endocrine system to your metabolic health. It details the pathways, signals, and clinical strategies that influence this vital connection. This knowledge serves as a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive concern to one of proactive understanding.

Your personal health narrative is written in the language of your own unique physiology. Recognizing how hormonal balance translates directly into cellular function is the first principle of authoring your own story of vitality. The next step in this process is to translate this foundational knowledge into a personalized protocol, guided by clinical data and a deep appreciation for your individual biological context.